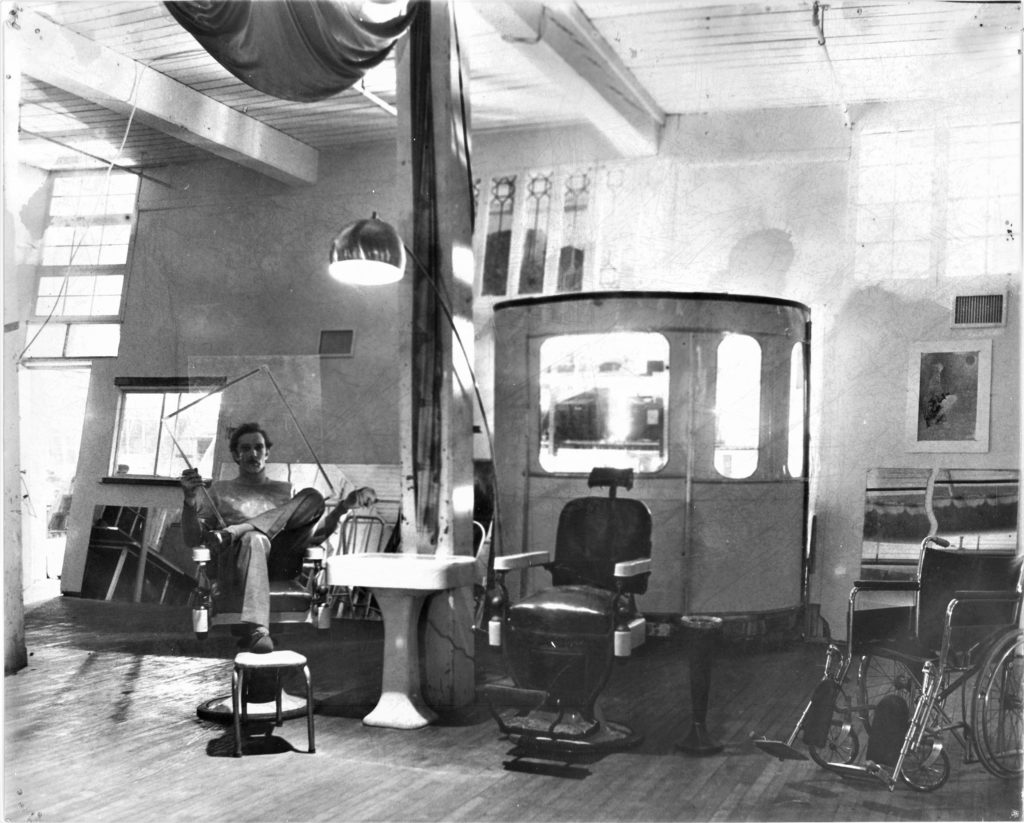

Tony Yagovane and two tenants in the interior courtyard of the former New Haven Clock Factory, c. 1980. Collection of Jason Bischoff-Wurstle, used by permission

By Jason Bischoff-Wurstle

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

As the transformative era of urban renewal and heavy losses of industry and population in New Haven in the 1970s began to diminish, the city was littered with massive empty 19th-century factory buildings. The New Haven Clock Company factory complex on Hamilton Street was one of these leftovers. Once the largest manufacturer of affordable timepieces in the world, it was now a relic of the past in need of new life.

In 1980 Tony Yagovane bought the old clock-factory complex. In interviews I conducted in 2019 for the New Haven Museum’s FACTORY exhibition (on view through July 2020) with former tenants Paul Rutkovsky, Beverly Richey, and Dimitri Rimsky and developer Bill Kraus, Yagovane was described as an eclectic, amiable entrepreneur who was always there with interest and support for his tenants—as long as he got his rent.

Paul Rutkovsky founded the Papier Mache Video Institute, or PMVI, in 1978. PMVI was a group of artists that focused on activist art of a transient nature not typically exhibited at the time in museums and galleries. PMVI took on issues of feminism, war, capitalism, elitism, urban renewal, and the consuming culture of television through works of music, dance, poetry, visual art, performance, mixed media, papier-mâché, and video. PMVI’s work and exhibition space was located on the wide-open fourth floor of the north side of the factory, where, as the only occupants, the group had free rein to create art and host events.

Rutkovsky, a fellow at Harvard’s Institute for the Study of the Avant-Garde, saw museums and galleries as exclusive “Cathedrals for A-R-T,” as he called them, entrenched in the business of the capitalist-elitist art world. He sought to foster creativity in people by engaging them in the creation of art.

In 1983 Rutkovsky left New Haven for a teaching position at Florida State University, and his colleague Beverly Richey took over leadership of PMVI. She was producing groundbreaking feminist art and was the driving force behind PMVI’s legendary one-day, 30-artist 1984 exhibition. After a year of planning in which the artists came together under Richey as a cohesive and inclusive group exhibiting their best strengths, the show had crowds of visitors lining up around the dilapidated city block. More than 700 people attended the show. Richey speculates that nothing had been done on this scale before in New Haven outside of Yale University.

Dimitri Rimsky in his studio at the former New Haven Clock Factory, c. 1987. Collection of Jason Bischoff-Wurstle, used by permission

In the early to mid-1980s other artists and musicians began to live in and use the spaces in the complex, according to Bill Kraus, a historic rehabilitation consultant and developer. (Kraus isresponsible for spearheading the nearly 20-year effort to convert the clock factory complex into apartments.) The north side became home to a notable artist live/work community pioneered by the Petaluers, a troupe of mimes led by Dmitri Rimsky. Rimsky and a group of seven other artists worked to build a true do-it-yourself arts community in the building, which Rimsky dubbed the Hamilton Street Lofts. Yagovane was supportive and charged minimal rents of $100 to $200 a month for 1,400-square-foot studios. The problem was that, like most municipalities in the country at the time, the city did not allow residential housing in an industrial zone.

The Petaluers were ubiquitous in the 1980s New Haven restaurant and club scene, selling flowers for $1 apiece to customers three days a week. They often made their entire months’ rent in one night and were free—at least in the eyes of the building’s owner—to create a landscape of their making in the former clock factory. With the help of another Hamilton Street tenant, a lawnmower repairman known as Goodie, they salvaged materials from throughout the massive factory and dumpsters across the city and installed their own electric, gas, and plumbing lines.

From Rimsky’s perspective, everything they did went toward achieving absolute artistic freedom. But without a proper certificate of occupancy from the city, the group was constrained by the illegality of their living situation. They couldn’t expand the cultural community further than what they could contain and sustain under their circumstances. They ultimately hoped to be grandfathered in to a legal living situation with a zoning change to a live/work use, but in 1988 an accidental fire in their space brought a swift end to the community and that trajectory.

Attempts were made in the late 1980s and again in the early 2000s by Yagovane, and later the New Haven Arts Council, to rehabilitate and establish legitimate artist live/work spaces in the complex. Today, under the guidance of Kraus, those attempts and the entire postindustrial history of the New Haven Clock Company factory are nearing fruition. For nearly two decades Kraus has persevered in bringing affordable housing online in the old complex, with the hope that new generations will find this historic building a place to create in.

Jason Bischoff-Wurstle is the director of photo archives at the New Haven Museum and curator of FACTORY.

Explore!

FACTORY, a special exhibition about the New Haven Clock Factory

On view through July 2020

New Haven Museum, 114 Whitney Avenue, New Haven

NewHavenMuseum.org