(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2018

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

By the end of the 19th century baseball was quickly becoming a national obsession. Baseball games materialized on every street, field, and patch of grass in the country. But on the village green in Litchfield, Connecticut, the game was notably absent. Writing to a town historian in 1930, Litchfield native Arthur E. Bostwick offered an explanation. Decades earlier Bostwick’s father had been crossing through town when a line drive “struck him in the eye and felled him senseless to the ground.” The elder Bostwick recovered from his brush with baseball, but the town banned America’s new pastime from the center green. Luckily, Litchfield could always turn to “Connecticut’s game”—wicket.

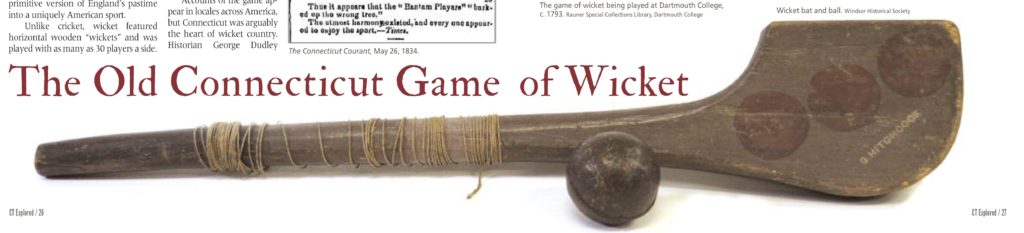

Wicket, or wicket ball, was a popular bat-and-ball game played by Americans in the years before baseball. Wicket lacks a definitive origin, though most historians of the game believe it developed from some early form of cricket imported to New England. Frederick Calvin Norton speculated in The Hartford Courantin 1904 that cricket “savored so much of the English aristocracy” that New Englanders gradually changed the game, shaping a primitive version of England’s pastime into a uniquely American sport.

Unlike cricket, wicket featured horizontal wooden “wickets” and was played with as many as 30 players a side. The game was usually played on an “alley,” a smooth patch of ground with a wicket at each end. Batters stood in front of each wicket and attempted to defend it using a long bat with a circular end. Bowlers tried to retire the batters by throwing or bouncing a ball across the alley and striking off the opposite wicket. If either batter recorded a hit, the two would complete a “cross” by running from one end of the alley to the other until “put out” by the bowler or fielder. The team with the most crosses at the end of the competition prevailed.

Some notable Americans tried their hands at wicket. George Washington, for instance, “dined with G Nox and after dinner did us the honor to play at Wicket with us,” Continental soldier George Ewing noted in his journal while stationed at Valley Forge in 1778. F. M. Green notes in Hiram College and Western Reserve Eclectic Institute: Fifty Years of History (Hubbell Printing, 1901) that future President James A. Garfield was one of the school’s best wicket players. The street in front of Garfield’s house even served as the wicket pitch.

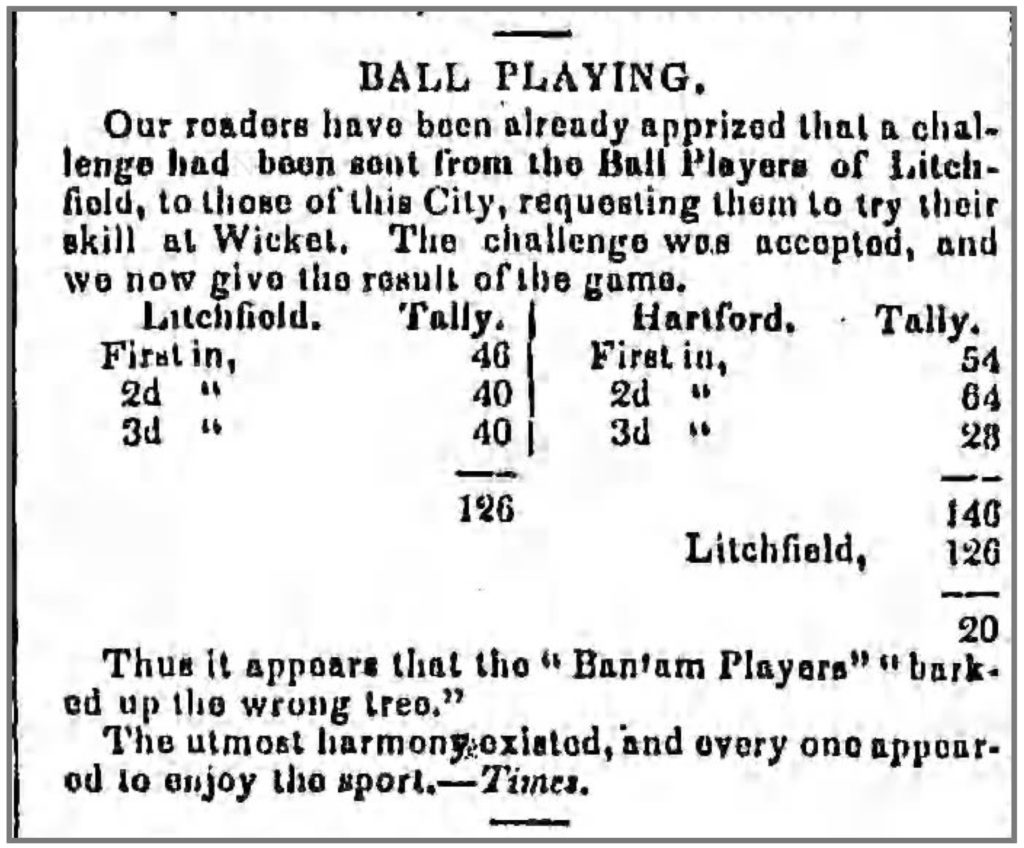

Accounts of the game appear in locales across America, but Connecticut was arguably the heart of wicket country. Historian George Dudley Seymour, in his paper “The Old-Time Game of Wicket and Some Old-Time Wicket Players,” noted that wicket was played in Connecticut “with practically unabated interest” for at least a century. Litchfield and New Hartford were “great centers for the game,” though Norton in TheHartford Courant cited Bristol as the town where “men and boys take to wicket playing as a duck will to water.”

In 1859, Bristol hosted a team from New Britain for the state championship. Bristol took the match, 190 to 152, on a field awash with more than 4,000 spectators. The Courantreported that the visitor’s train, which “was so gayly decorated” when it arrived that morning, left Bristol dressed in a “generous supply of black bunting.”

Yale students were frequent wicketers, but Storrs O. Seymour recalled in a 1909 letter that when he arrived in New Haven in 1853 the game had all but vanished. Seymour rallied a few classmates, procured “the ball and bats and wicket sticks,” and set to practicing. After one of the club’s matches, an old man approached Seymour, claiming to have played wicket in the “old town of Litchfield” with Seymour’s father, grandfather, and great-grandfather. The man was Asa Bacon, 86 at the time of their conversation. The game of wicket, it seemed, “must have been something of a cult in the Seymour family.”

As baseball swept the nation after the Civil War, wicket became an occasional tradition carried out by aging players in a few New England towns. Seymour described these games as “not exactly a revival, but rather as a matter of local pride” that gave wicketers “a chance to stretch their muscles.” In Muscle and Manliness: The Rise of Sport in American Boarding Schools(Syracuse University Press, 2005), Axel Bundgaard describes two baseball games in 1859 between a team from Washington’s Gunnery School and a “brawny nine” from Litchfield, “composed largely of old ‘wicket’ players.” Even Litchfield, one of the last refuges for Connecticut’s game, had given way to America’s pastime.

As baseball swept the nation after the Civil War, wicket became an occasional tradition carried out by aging players in a few New England towns. Seymour described these games as “not exactly a revival, but rather as a matter of local pride” that gave wicketers “a chance to stretch their muscles.” In Muscle and Manliness: The Rise of Sport in American Boarding Schools(Syracuse University Press, 2005), Axel Bundgaard describes two baseball games in 1859 between a team from Washington’s Gunnery School and a “brawny nine” from Litchfield, “composed largely of old ‘wicket’ players.” Even Litchfield, one of the last refuges for Connecticut’s game, had given way to America’s pastime.

Alexander Dubois is curator of collections at the Litchfield Historical Society. This story is based on “Litchfield and the Old Connecticut Game of Wicket,” available at litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/blog/?p=627.