(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

All photographs from Mystic Seaport, Photography Collection

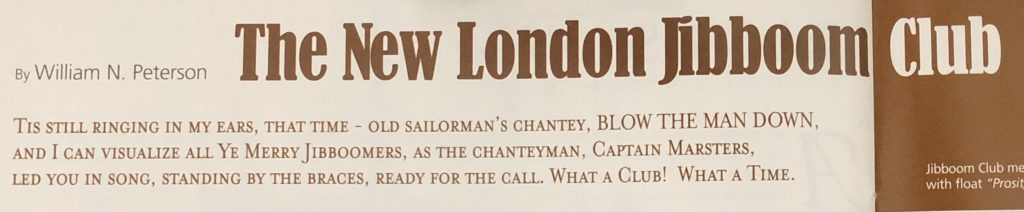

TIS STILL RINGING IN MY EARS, THAT TIME-OLD SAILORMAN’S CHANTEY, BLOW THE MAN DOWN, AND I CAN VISUALIZE ALL YE MERRY JIBBOOMERS, AS THE CHANTEYMAN, CAPTAIN MARSTERS, LED YOU IN SONG, STANDING BY THE BRACES, READY FOR THE CALL. WHAT A CLUB! WHAT A TIME.

So wrote Richard McKay (grandson of the famous East Boston ship builder Donald McKay), who in 1939 looked back on his first visit as an honored guest of New London, Connecticut’s Jibboom Club No. 1.

The Jibboom Club, a local seamen’s fraternal organization, was born of the salty history of New London, which like so many other coastal towns in New England is steeped in maritime tradition. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries New London was one of the leading seaports in New England. As its maritime commerce was more diverse than that of most seaports, its populace and their traditions were more diverse as well.

The New London Jibboom Club No. 1 developed as an eccentric fraternal organization made up of active and retired seafarers. (If another club had started in New Haven, it would be No. 2, and so forth, but the club never expanded beyond the New London region.) Though similar in some respects to other maritime-based groups that had formed in New England coastal towns during the age of sail, such as the much older Boston Maritime Society and East India Marine Society in Salem, Massachusetts or even its more contemporary Master Mariners’ Association in Gloucester, Massachusetts, the Jibboom Club was a far less formal organization. Although it was originally conceived of as an association of shipmasters and its first members were all working or retired master mariners, wealthy merchants didn’t dominate the group, nor, ultimately, did any specific category of seaman, as was the case with so many other groups. New London’s club not only included fishermen but whalemen, steamboat men, yachtsmen, packet captains, naval officers, and others.

The Jibboom Club originated in 1871 when a group of sea captains began meeting informally at various locations around New London’s waterfront. For a time there were even informal satellite or branch clubs in Noank, Groton, and Mystic. The Mystic Jibboomers apparently had metamorphosed from a group of sea captains who had been meeting informally since the mid-1860s known as The Mystic Pinafore Club. The Mystic Press newspaper kiddingly chided in 1884 that “…this gobbling up of an entire club, by the terrible Jib-boomers is something that should not be tolerated.” The gobbled apparently acquiesced: in 1888 Captain Henry Wells of Mystic, a Pinafore Club stalwart, named his new little pleasure yacht “Jibboom Club.”

The New London Jibboom Club, however, was not officially incorporated until 1891, when the satellite groups consolidated with the parent organization in New London. The physical reorganization was made possible by the 1889 completion of New York, Providence, and Boston Railroad’s bridge over the Thames River. The Thames had been the last geographical barrier to the long-sought direct rail link between New York and Boston. Locally its competition made it much easier for members living east of the river to reach New London — and the club’s monthly meetings.

The group adopted by-laws, including a resolution stating simply that “this club is formed for the purpose of social enjoyment and the promotion of good fellowship amongst its members.” Initiation rituals were also formalized in 1891, and the old club rooms over the Bank Street store of ship chandlers Darrow & Comstock were redecorated to accommodate the group.

To be a member of the Jibboom Club you had to prove two years of experience as sea. The 1891 reorganization opened membership to any legitimate mariner. At first, the two-sea-year requirement was strictly upheld: as late as 1904 William H. Allen, a veteran of New London’s whaling fleet, could still write that “…its active members are composed of sailors. Among these you will find naval officers, commanders, and engineers of ocean and inland steamers and gentlemanly yachtsmen. In short every class of marine service is included.”

During its heyday, from 1891 to 1926, the Jibboom Club had almost 400 active members including nearly 50 men, according to one report, from the tiny fishing village of Noank! Associate and honorary members included prominent businessmen and local politicians who generally had little interest in the daily life of the club but who performed some service for the organization or whose names lent it prestige. United States Congressman Charles A. Russell was such a member, as was Charles D. Boss of C. D. Boss & Co., manufacturer of ships’ biscuits. Another was Sebastian D. Lawrence, a former whaling agent and president of the New London Whaling Bank. Lawrence owned the Exchange Building in which the club met after 1894 and became so fond of the old salts that be bequeathed the Jibboomers $1,000 in 1910. He had also donated objects for the club’s impressive and growing collection of curiosities, souvenirs, and relics.

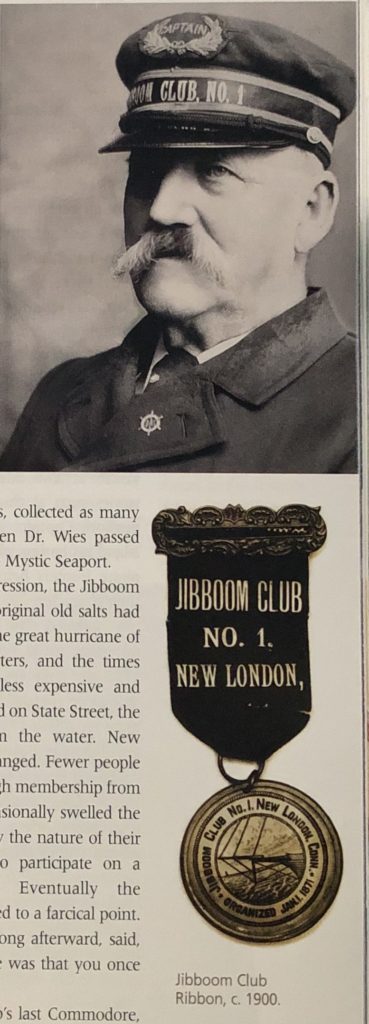

At the first meeting of the reorganized club in 1891 the new members elected George W. Moxley, a popular veteran of New London’s fishing and coastal fleet, as “Commodore,” the club’s highest office. Former whaling master turned steamboat captain James F. Smith was elected “Captain,” the second highest office. Both were re-elected the following year. In 1893 another fishing sloop captain, James H. Weeks, was elected Commodore, and Captain Dudley A. Brand from Mystic was elected Captain. Brand was well known along the shores of New England as the versatile master of coasting schooners and pleasure yachts. Smith and Brand also served two years in office, which seems to have established an informal precedent.

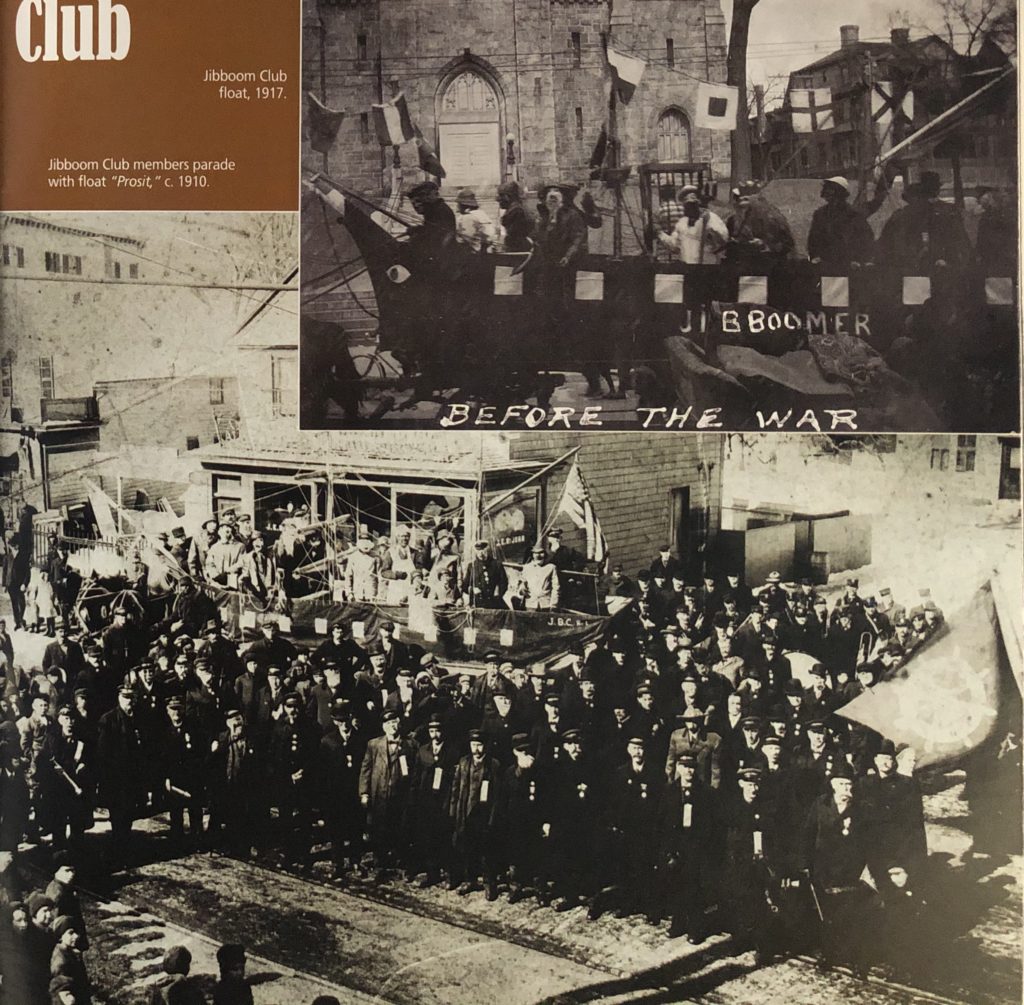

top: Jibboom Club float, 1917. bottom: Jibboom Club members parade with float “Prosit,” c. 1910. Mystic Seaport Museum

Afterward the club occupied the rooms over the Darrow &Comstock ship chandlery, although its very first official club room prior to this was located in the Bank Street rigging loft of Captain John Haynes, who some credit with establishing the club in 1871. However, in 1894, after a disagreement with Darrow & Comstock over repairs to the building (particularly a set of outside stairs that frequently iced over in the winter), the club moved to the Lawrence Building, also on Bank Street. The new location afforded a “terrific view” of New London harbor, according to one member.

The Jibboom Club’s few rules were strictly enforced. Ladies were not allowed in the club rooms excepted on special occasions. Alcohol was forbidden, as was playing cards for money. Swearing was officially frowned upon, though apparently hard to regulate. On the front wall of the main club room was a miniature ship’s bow representing the “good ship Jibboomer,” whose function was to remind the Jibboomers of their fraternal bonds. Their quarters in the Lawrence building took up the whole second floor. Aside from the main clubroom there was an anteroom for initiation rites, a dining room, banquet hall, and galley. The steward was in charge of the galley, which was located off the dining room and was especially important facility for the members.

The monthly meetings were held “between the decks” in the club rooms and included ceremonies reminiscent of Masonic or Odd Fellows rituals but with a maritime twist. Besides the presiding officers of Commodore and Captain, other officers were identified as 1st Mate, 2nd Mate, Purser, Boatswain, and Steward. Meetings called “voyages” or “cruises” did not convene or adjourn but “weighed” and “came to anchor.” Likewise, votes did not pass but had to “clear fore and aft,” meaning that new members, particularly, had to be accepted by all the club officers and regular members alike. In fact, as was common at that time, the club adopted a black-ball system for electing new members. One anonymously cast black ball and you were not elected. Once elected, however, the new members “shipped as able seamen.”

The long, drawn-out initiation ceremony involved the inevitable secret handshake and passwords along with a set of rehearsed protocols culminating in the candidate’s gaining permission to come aboard the good ship Jibboomer. The ceremony climaxed with the new member’s being allowed the privilege of “going aloft,” climbing a rope ladder rigged from floor to ceiling. The initiation clearly was fun, though; it included the impossible task of dunking for doughnuts in a water bucket. The new member also had to swear “not to eat hard bread when he could get soft, and not drink salt water when he could get fresh.” Members paid due homage with a tip of the hat upon entering an anteroom on whose walls prominently hung a “large whale’s penis.”

The Jibboom Club was perhaps best known for its famous annual Washington’s Birthday parade and celebration, which began in 1908 and continued for 50 years. George Washington, for some now unknown reason, was chosen as the “patron saint” of the Club. Some of the club’s Yankee wags were quick to remind skeptics that Washington did make at least one dangerous and fateful voyage across the Delaware River, and that was good enough for them! On Washington’s Birthday all the “Jibboomers” would gather on Bank Street in front of the club rooms where a large float was made ready for the parade. The float took the form of “the good ship Prosit.” Prosit, named for a German drinking toast meaning “may it do good,” was placed on a horse-drawn carriage and then paraded along the main streets of New London to the accompaniment of a drum band.

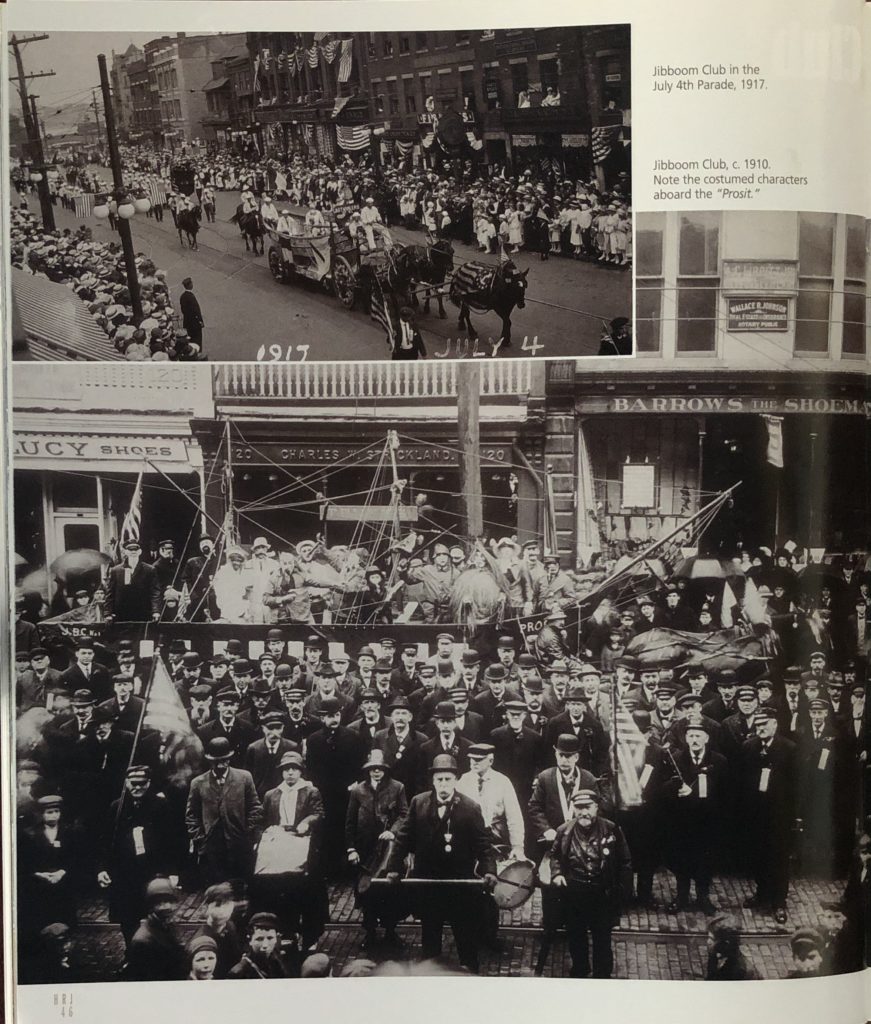

top: Jibboom Club in the July 4th parade, 1917. bottom: Jibboom Club, c. 1910. Note the costumed characters aboard the “Prosit.” Mystic Seaport Museum

Most of the members walked alongside or behind the float wearing official Jibboom Club badges and hats, but some would ride on deck dressed in outlandish costumes reminiscent of those typically worn during a shipboard crossing-of-the-equator ceremony. King Neptune was always prominently featured among the group.

At the end of the parade and on other occasions throughout the year, the club held a chowder dinner for members and invited guests. Captain “Jerry” Keeney, the club steward in the mid-1809s, became known for his famous clam chowder and consequently was re-elected to that office for many years running. One year, however, it proved impossible to get enough clams, so oysters were substituted, which turned out to be a “very acceptable” alternative, according to a local newspaper report. Thereafter oysters were as commonly used as clams. “Making a chowder for 300 people is no small job, but Captain Jerry has never been known to fail” reported the New London daily paper The Day.

Captain E. John Brown was another popular steward also known for his chowder. These hearty repasts were cooked in a huge cauldron “in which steamed and sputtered” 16 gallons of clams (or oysters), 3 bushels of potatoes, half a peck of onions, and 10 pounds of fat pork. The meals also included cold meat, hard and soft tack, and coffee.

top: Capt. James Francis Smith, captain of the steamers Old Glory and Manhanset, in his Jibboom Club uniform, c. 1905. photo: E.A. Scholfield. bottom: Jibboom Club ribbon, c. 1900. Mystic Seaport Museum

After the meal eight bells were struck, calling those present to turn “from refreshment to labor” to hear politicians of clergymen speak well into the evening. The club for a time even had its own official “Orator” who, if called upon, could speak on any topic. For many years this post was held by George T. Marshall, New London’s surveyor of vessels for the American Shipmaster’s Association. A verse in a Jibboomers’ poem states “George Marshall is our Orator, We have no doubt or fear, But what he’ll always do his best, And make his subject clear.” Though the club’s minutes indicate Marshall could be a bit of a contrarian, and the club abolished the post after his resignation in 1898, “there isn’t a jollier crowd in town than the Jibboomers” reported the New London Morning Telegraph in 1891, “…and their hearts and pocket books are open for the general good.”

During less celebratory times the members would sit around the “big stove” in the main club room and swap yarns, smoke pipes and cigars, or read the newspaper or books from the Jibboom Club Library. The club rooms were open year round, though monthly meetings were suspended in the summer. The pool table was always busy, and sea chanteys were also a popular diversion. The Jibboomers prided themselves on their repertoire of sea songs, and many members stayed after the monthly meetings to practice their chanteys. The ditty “Santa Anna” apparently was a particular favorite. One observer noted that the “Commodore intones the first lien and the response is a vociferous chorus by the assembled shipmates, who seem to get a lot of fun out of the exercise … and it is a very interesting experience to listen to the old salts rip the barnacles out of their throats.” The most popular activity though, was cribbage. Captain Ellery Thompson, one of the club’s latter members, recalled that every time he visited the club rooms “someone was always at the cribbage boards.”

During its most active period of operation the Jibboom Club collected, and displayed hundreds of objects, relics, and curiosities related to the members’ seafaring experiences. Objects were donated by admiring friends such as Richard McKay, who, upon the occasion of his 1939 visit, gave the club a portrait of Donald Mckay and a picture of the launching of the McKay and a picture of the launching of the McKay-built ship Great Republic. For a time the club rooms were veritable museum galleries. Paintings, lithographs, photographs, “mammoth oyster shells,” swordfish bills, seashells from the four corners of the earth, and ship models were all displayed wherever space permitted, along with a figurehead from the long-lived New London-owned ship Flora, another from the whaleship Julius Caesar, and scores of artifacts related to New London’s whaling industry such as harpoons, lances, bomb lance guns, and cutting spades. One of the most prized objects was a framed Seamen’s Protection Certificate issued in 1830 by New London Customs Collector Richard D. Law to seaman Samuel A. Barnes, also of New London. Seamen’s Protection papers were among a sailor’s most important documents because they recognized him as a citizen of the United States and “protected” him from seizure by foreign navies. The Jibboomers, mariners all, duly respected this old piece of paper, which to them was emblematic of the sailor’s value as a citizen to the nation.

Ernest Gates, “Curator for Life” of the club’s extensive library, collected whaling-related objects and was particularly interested in scrimshaw with New London associations. He eventually amassed a large personal collection of his own. Sadly, his wife, to make ends meet after Ernest’s death, sold nearly all of his collection. Since that time, though, some of those objects have resurfaced on the antiques market, and many, particularly those with Jibboom Club associations, have been added to the Mystic Seaport collection. In 1956, when the club began to wind down its affairs, many items were liquidated to help pay the club’s mounting bills. The few remaining club members bought some of the objects, but most were sold on the open market. Mystic Seaport acquired log books, journals, photographs, and waling implements. The late Dr. Carl Wies, who, along with his wife Alma, ran the Tale of the Whale Museum on “Whale Oil Row” in New London for many years, collected as many Jibboom Club items as possible. When Dr. Wies passed away his collection went by bequest to Mystic Seaport.

As the country fell into The Depression, the Jibboom Club went into decline. Most of the original old salts had died or become inactive in the club. The great hurricane of 1938 badly damaged the club’s quarters, and the times dictated that the new quarters be less expensive and consequently less commodious. Located on State Street, the new rooms were also remote from the water. New London’s maritime milieu had also changed. Fewer people made their living from the sea. Although membership from naval and Coast Guard personnel occasionally swelled the ranks, these members tended to be, by the nature of their occupations, transient and unable to participate on a monthly or even yearly basis. Eventually the sea-experience requirement was relaxed to a farcical point. Club member Fred Smith, reflecting long afterward, said, “towards the end all you had to prove was that you once rode on the [Thames River] ferry.”

In 1959 Louis Jennings, the club’s last Commodore, along with the remaining 10 members of the once proud and jolly organization, had the sad duty of winding up the Jibboomers’ affairs. “Ships still slip down the Thames River to the sea” noted The Day on December 31, 1959, but “the days of the old seafaring men have passed.”

William N. Peterson was the Carl C. Cutler Chair of Maritime History and Material Culture at Mystic Seaport Museum and was guest editor of this issue.

Explore!

Read more stories of Maritime Connecticut in the Spring 2009 issue and on our TOPICS page.