By Nancy R. Savin

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Winter 2022-23

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

At the intersection of Route 85, the Hartford-New London Turnpike, and Route 161 in Montville a gently sloping hillside site lies unseen behind a protective row of tall sturdy oak trees. Each spring the field grasses and invasives pop up in full force, then die out in the fall. One hardly expects to find there a beautiful Mount Rushmore granite monument dedicated during the Town of Montville’s Bicentennial Celebration in 1986, the newly rehabilitated stone rubble foundation of a rural synagogue erected in 1892, or the ruins of a nearby community house. But this small plot of land was the nerve center of The New England Hebrew Farmers of the Emanuel Society (NEHFES), the vibrant Russian Jewish immigrant community that flourished in Chesterfield, Connecticut from 1891 until the late 1940s.

Both my maternal and paternal forebears came to Chesterfield as immigrants in the 1890s. My memories of childhood visits to grandmother Sarah Ritch Savin’s farm in the 1940s, our great table-thumping Pesach seders, strewing corn to clucking chickens, visits to my great-grandfather’s general store, enjoying Kosofky’s swimming hole, and, perhaps best of all, the warm, soothing drone of men’s voices chanting in Hebrew in the one-room wooden synagogue, are marvelous and heartfelt.

But how did these “Russian Hebrews,” as The New York Times called them in a November 12, 1892 article, come to Chesterfield? It is an interesting story, one that Samuel J. Lee shared in his book Moses of the New World: The Work of Baron de Hirsch (Thomas Yoseloff, 1970). Appalled by excessive restrictions against Russian Jewry—prohibitions against owning land and entering professions, a 25-year mandatory military conscription for young men, and the violent government-sponsored anti-Jewish pogroms of the 1880s—the elegantly mustached German Jewish Baron Maurice de Hirsch auf Gereuth, a banker and industrialist who completed the Paris-Istanbul Orient Express in1889, decided to do something about it. “I am ready to stake my wealth and my intellectual powers, to give to a portion of my companions in faith the possibility of finding a new existence, primarily as farmers, and also as handicraftsmen, in those lands where the laws and religious tolerance permit them to carry on the struggle for existence as noble and responsible subjects of a humane government.” In 1889 de Hirsch established secular and vocational education programs via his Alliance Israelite Universelle in Paris and a Jewish Colonization Association in London. His American de Hirsch Fund, capitalized in New York City in 1891, functioned as a private bank that provided personal mortgages for a small down payment. The Chesterfield community was one of the earliest of many de Hirsch “colonies” in Connecticut; others were located in towns such as Ellington, Hebron, and Columbia.

But how did these “Russian Hebrews,” as The New York Times called them in a November 12, 1892 article, come to Chesterfield? It is an interesting story, one that Samuel J. Lee shared in his book Moses of the New World: The Work of Baron de Hirsch (Thomas Yoseloff, 1970). Appalled by excessive restrictions against Russian Jewry—prohibitions against owning land and entering professions, a 25-year mandatory military conscription for young men, and the violent government-sponsored anti-Jewish pogroms of the 1880s—the elegantly mustached German Jewish Baron Maurice de Hirsch auf Gereuth, a banker and industrialist who completed the Paris-Istanbul Orient Express in1889, decided to do something about it. “I am ready to stake my wealth and my intellectual powers, to give to a portion of my companions in faith the possibility of finding a new existence, primarily as farmers, and also as handicraftsmen, in those lands where the laws and religious tolerance permit them to carry on the struggle for existence as noble and responsible subjects of a humane government.” In 1889 de Hirsch established secular and vocational education programs via his Alliance Israelite Universelle in Paris and a Jewish Colonization Association in London. His American de Hirsch Fund, capitalized in New York City in 1891, functioned as a private bank that provided personal mortgages for a small down payment. The Chesterfield community was one of the earliest of many de Hirsch “colonies” in Connecticut; others were located in towns such as Ellington, Hebron, and Columbia.

My maternal great-great-grandfather, Hirsch Kaplan, born in Pereyaslov, south of Kiev, Ukraine, arrived in New York in December 1887. As an unordained rabbi, he had organized a small group of fellow Jewish immigrants. When they learned about inexpensive farmland in Connecticut in 1890, they organized as Agudas Achim (Hebrew for a community of brethren) and left Williamsburg via ferry to New London, then traveled for another two and a half hours by horse and wagon north to Chesterfield. My great-aunt Molly left us a description of the group’s joyful parade down to the docks of Brooklyn, with her father at its head, carrying a new torah.

By April 28, 1892 there were 56 families and 503 individuals in Chesterfield. And what did the Yankees think of their Russian Hebrew neighbors? In “Farms and Factories: Late News and Gossip Concerning Chesterfield’s Curious Colony” (New London Day, April 26, 1892), a local reporter observed that “ . . . in almost every household a lucrative little domestic factory industry is carried on. All day the rattle of sewing machines is heard in the rural streets and men, women and children ply the trade of coat and shirt making from dawn until late at night.”

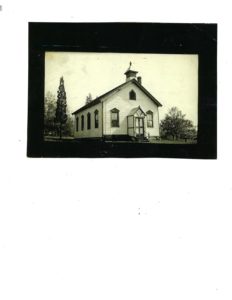

Pooling their profits, the families purchased 1.47 acres from Ellen A. and Charles H. Tillotson for $70 on January 15, 1892. I think the gurgling brook from Powers Ice Pond across the road made it the perfect location for their envisioned synagogue, mikveh, and creamery. The de Hirsch Fund gifted them $900 to build a one-room wooden synagogue with Victorian fish-scale shingles on its façade, decorative sun bursts above the windows, and a small Jewish star over the entranceway.

The de Hirsch Fund also wrote a loan for $3,000 to “New England Hebrew Farmers Creamery Association” for a steam-driven creamery to produce butter and cream. The group changed its name to The New England Hebrew Farmers of the Emanuel Society, fashioned a great mission statement, and wrote a stringent governing constitution, which we recently discovered when we translated our most precious artifact, a handwritten, in Yiddish, Minutes and Ledger Book.

The de Hirsch Fund also wrote a loan for $3,000 to “New England Hebrew Farmers Creamery Association” for a steam-driven creamery to produce butter and cream. The group changed its name to The New England Hebrew Farmers of the Emanuel Society, fashioned a great mission statement, and wrote a stringent governing constitution, which we recently discovered when we translated our most precious artifact, a handwritten, in Yiddish, Minutes and Ledger Book.

While Hebrew is the liturgical language of the Torah and other Jewish prayers, Yiddish was the language spoken and written by European and Russian Jewry from the 12 to the 19th centuries. Yiddishist Miriam Leberstein’s translation of its cursive entries revealed a wide range of the synagogue activities, almost one hundred names of participating members, the constitution, and details such as how much it cost to have a cow or a chicken ritually slaughtered. Judaic religious practice insists on the slaughter of animals in a respectful, mindful way. The facsimile and its translation are online at the YiddishBookCenter.org’s Steven Spielberg’s Digital Archive.

The New London Day, New York Sun, tPittsburgh Dispatch, New York Post, and other newspapers were intrigued by the colony and its progress. In 1897 The New London Day reported “Hebrews Very Poor: Destitution among Baron de Hirsch’s Colony.” The rocky soil and hard winters proved challenging, and the population dwindled to 33 families. Felicitously, however, streams of summer boarders and relatives, seeking respite from the noise and heat of New York, began to come to Chesterfield at the turn of the century. They paid $7 a week for great Jewish cooking, swimming,barn dances, and, perhaps, a chance to meet one’s future wife or husband! In her memoir I Remember Chesterfield, my mother, Micki Solomon Savin, vividly describes the community and this entrepreneurial phenomenon, which lasted well into the 1920s.

Their children learned English in Chesterfield’s one-room schoolhouse, attended New London’s Bulkeley High School, married, and left Chesterfield to start businesses. I am fond of telling the story of my Uncle Butch (A. I.) Savin, who recalled being “dirt poor” when growing up. Without a full high-school education, he established a construction company, one of the 14 that built the Merritt Parkway, that also built the Charter Oak Bridge in Hartford, the Baldwin Bridge at the mouth of the Connecticut River in Old Saybrook, and the Gold Star Bridge in New London in the 1940s. Moses Savin became the mayor of New London and served in the Connecticut State Legislature. Many second-generation descendants started significant business in New London, Hartford, Norwich, and beyond.

Their children learned English in Chesterfield’s one-room schoolhouse, attended New London’s Bulkeley High School, married, and left Chesterfield to start businesses. I am fond of telling the story of my Uncle Butch (A. I.) Savin, who recalled being “dirt poor” when growing up. Without a full high-school education, he established a construction company, one of the 14 that built the Merritt Parkway, that also built the Charter Oak Bridge in Hartford, the Baldwin Bridge at the mouth of the Connecticut River in Old Saybrook, and the Gold Star Bridge in New London in the 1940s. Moses Savin became the mayor of New London and served in the Connecticut State Legislature. Many second-generation descendants started significant business in New London, Hartford, Norwich, and beyond.

By 1950 the Society had gone defunct, and in 1975 the synagogue was torched and burnt to the ground. Although we had erected the monument, it was not until 2006 that, via the deft skills of my friend Hartford attorney Karl Fleischmann, that a devoted coterie of 20 descendants and I reactivated NEHFES as a 501(c)(3) corporation in the State of Connecticut. We took possession of the land our ancestors settled, eager to protect and preserve the site and its legacy.

By 1950 the Society had gone defunct, and in 1975 the synagogue was torched and burnt to the ground. Although we had erected the monument, it was not until 2006 that, via the deft skills of my friend Hartford attorney Karl Fleischmann, that a devoted coterie of 20 descendants and I reactivated NEHFES as a 501(c)(3) corporation in the State of Connecticut. We took possession of the land our ancestors settled, eager to protect and preserve the site and its legacy.

Our passion, the financial support of NEHFES descendants, and a hard-working board of directors have been critical, but it has only been with the superb collaboration of numerous Connecticut state agencies and individuals that we have made progress.

Early on, the Connecticut State Historical Commission’s Mary M. Donohue and former Connecticut State Archaeologist Dr. Nicholas F. Bellantoni were our greatest champions. Dr. Bellantoni has called the site “An archaeological gem!” Robert Cless of the Connecticut Department of Transportation was also an early advocate. In recent years, the State Historic Preservation Office’s Catherine Labadia has been an invaluable friend and mentor to NEHFES and to me. There are so many others to whom we are grateful for their interest and guidance, including Preservation Connecticut, HPI Inc., Cirrus Structural Engineering, Star Survey Inc., and Derek Pepin Masonry.

Based on an archaeological survey by Bruce Clouette, the New England Hebrew Farmers of the Emanuel Society Synagogue and Creamery Site was named Connecticut’s 24th State Archaeological Preserve in 2007 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places on the strength of a nomination written by Historical Perspectives Inc. in 2012. In 2017 we negotiated a constraining easement on the creamery parcel of the site with the Connecticut Department of Transportation,which they bought in anticipation of road improvements to the intersection in 2001.

Last June I signed a document transferring title to the synagogue and community house portion of the NEHFES site to The Archaeological Conservancy, or TAC, the preeminent conservator of hundreds of historic and significant archeological sites across America. They will call it The New England Hebrew Farmers of the Emanuel Society Synagogue and Shoyket’s House Preserve. We are working with Kelley Berliner, TAC’ s Northeast Regional Director, on the creation of a new TAC – NEHFES management committee for further research, protection, and enhancements. One interesting feature in the basement of the “community house” is the mikveh, a replica of a 2,500-year-old Judaic stepped ritual bathing pool. The mikveh was the subject of a three-week University of Connecticut Field Archaeology School excavation co-directed by Dr. Bellantoni and Dr. Stuart S. Miller in 2012.

Last June I signed a document transferring title to the synagogue and community house portion of the NEHFES site to The Archaeological Conservancy, or TAC, the preeminent conservator of hundreds of historic and significant archeological sites across America. They will call it The New England Hebrew Farmers of the Emanuel Society Synagogue and Shoyket’s House Preserve. We are working with Kelley Berliner, TAC’ s Northeast Regional Director, on the creation of a new TAC – NEHFES management committee for further research, protection, and enhancements. One interesting feature in the basement of the “community house” is the mikveh, a replica of a 2,500-year-old Judaic stepped ritual bathing pool. The mikveh was the subject of a three-week University of Connecticut Field Archaeology School excavation co-directed by Dr. Bellantoni and Dr. Stuart S. Miller in 2012.

In November 1883 the sixth-generation American Jewish poet Emma Lazarus, whose ancestors were among 23 Spanish Jews who arrived in Nieuw Amsterdam in 1654, penned her famous sonnet “The New Colossus” to help raise money for the Bartholdi Pedestal Fund for the Statue of Liberty. As Esther Schor explains in her biography, Emma Lazarus (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2017), it was our Russian Jews, then beginning to arrive in New York City, whom she called “the huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

I believe it’s important to remember and celebrate the ethics and determination of the original NEHFES congregation, who were but a sliver in the rich history of a people that stretches across millennia, cultures, and continents. Today our NEHFES member descendants are more than 40 families living in 13 states and Canada. They and other descendants are making mainstream contributions in the fields of business, science, medicine, law, media, arts, government, education, academia, and more.Their success speaks to the welcoming State of Connecticut and to America’s quintessential and transformative immigration paradigm.

Nancy R. Savin graduated as a major in Voice and Music History from Connecticut College and worked as a writer, producer, and host of arts and preservation programs for CPTV for 17 years. She initiated Connecticut’s first statewide surveys of historic theaters and historic synagogues and was the 2022 recipient of the Harlan H. Griswold Award for Historic Preservation.

Explore!

For more information about NEHFES visit newenglandhebrewfarmers.org.