by Johnna Kaplan FALL 2016

In 2015, when Connecticut abolished the death penalty—embedded in its laws since the 17th century—University of Connecticut history professor Lawrence Goodheart’s The Solemn Sentence of Death: Capital Punishment in Connecticut (University of Massachusetts Press, 2011) was widely cited in support of that change. Among the cases he brought to light for discussion in the media of the present was a disquieting case from more than a century ago.

In 2015, when Connecticut abolished the death penalty—embedded in its laws since the 17th century—University of Connecticut history professor Lawrence Goodheart’s The Solemn Sentence of Death: Capital Punishment in Connecticut (University of Massachusetts Press, 2011) was widely cited in support of that change. Among the cases he brought to light for discussion in the media of the present was a disquieting case from more than a century ago.

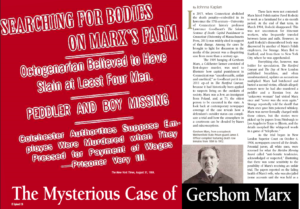

The 1905 hanging of Gershom Marx, a Colchester farmer convicted of first-degree murder, was used to illustrate how capital punishment in Connecticut was “unenforceable, unfair and unethical,” as Goodheart put it in a 2011 op-ed in The Hartford Courant, because it had historically been applied to suspects living on the outskirts of society. Marx was a Jew, an immigrant from Poland, and, at 73, the oldest person to be executed in the state. A look back at contemporary newspaper coverage of the case reveals how a defendant’s outsider status can complicate a trial and how the atmosphere in a courtroom can be clouded by biases and misconceptions.

These facts were not contested: Marx hired Polish native Pavel Rodecki to work as a farmhand for a six-month period. At the end of that term, in March 1904, Rodecki disappeared. This was not uncommon for itinerant workers, who frequently traveled between farms and mills. However, in April Rodecki’s dismembered body was discovered by another of Marx’s Polish employees, Joe Strange. Marx fled to Hartford, and from there to New York City, where he was apprehended.

Everything else, however, was fodder for speculation. The Hartford Courant and The Day of New London published breathless, and often unsubstantiated updates as accusations multiplied: Marx had butchered and buried a second victim, officials alleged; rumors were he had also murdered a peddler and a Russian boy. An “unknown woman” had visited Marx once and “never was she seen again.” Strange reportedly told the sheriff that Marx once gave him poisoned whiskey. Marx was never formally charged with those crimes, but the stories were picked up by papers from Pittsburgh to Los Angeles to Texas to Illinois, and the details morphed like whispered words in a game of “telephone.”

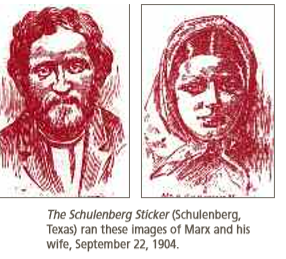

As the trial began in New London Superior Court on October 6, 1904, newspapers covered all the details. Potential jurors, all white men, were screened for what the Meriden Morning Record called “anti-Semitic tendencies, acknowledged or suspected,” illustrating that there was some sensitivity to the possibility of Marx’s receiving an unfair trial. The papers reported on the failing health of Marx’s wife, who was also jailed (some accounts said she was held as a witness for the state, others that she was charged as an accomplice in the murder) and the fact that the couple’s four young children were sent to the poorhouse.

Reporters described the spectators—The Day noted that “even a casual scrutiny… revealed the fact that the majority are members of the prisoner’s race”—and the testimony of a succession of witnesses, mostly Jewish or Polish immigrants whose words were translated by a court interpreter, leaving ample room for misunderstanding and error. The newspaper described Marx, too, in the dramatic manner and stereotype-laden language typical of the era. He had a “wizened face and bent figure,” and “the lines about his mouth indicate that he is cruel and selfish.” He had a “high pitched whining voice and a cringing manner.” He spoke English “tolerably well.” On the day of his conviction, he ate an apple “with apparent relish,” but after the verdict was read, he was carried to his “cage,” “weeping piteously.”

State v. Marx was not the only death-row case underway and in the news. On September 30, 1904 The Day proclaimed: “WATSON, HARTFORD MURDERER, TO DIE.” Joseph Watson, a “Negro lad” accused of shooting his boss, had told the judge at his trial, “You fellows all have got the power. It is no use for me to say anything.” On October 19 The Day noted that officials “hoped to finish the Marx case” and proceed with “the trial of the four Italians charged with murder.”

But while many contemporaneous cases also featured outsiders as perpetrators (and often victims as well), the cultural and religious nuances that surfaced during Marx’s trial made this case especially complex. To comprehend the events surrounding the crime, the judge, jury, and observers would have had to learn about kosher laws, which could have explained how blood from slaughtered livestock got inside Marx’s house. They would have had to understand the significance of the Jewish Sabbath to know why some of Marx’s Jewish neighbors were surprised to see him as he fled toward Hartford on a Saturday. They would also have had to grasp the nature of the tension just beneath the surface of the relationships between Colchester’s Poles and Jews, who often shared a native language and country of origin but diverged considerably in their beliefs and customs. These matters, hinted at during the trial, were never fully explained to the court—or to the readers who eagerly consumed media coverage of the trial.

Also unspoken was how closely the accusations resembled those that had followed the Jews for centuries. The alleged motive—prosecutors said Marx killed Rodecki to avoid paying him—recalled an enduring characterization of Jews as avaricious. (The New York Times said Marx was driven by “an insane desire…to escape paying money to persons to whom he was indebted.”) The timeline of the crime overlapped with both Easter and Passover, the traditional season of the blood libel, or false accusation of Jewish ritual murder. In Europe, from whence Marx and many of his Colchester neighbors came, blood libels had spawned persecution and mass killings of Jews. Marx’s lawyers did not know, or did not see fit to mention, that this could have influenced their client’s behavior in running away while Strange (according to court proceedings) confronted him with accusations of murder and then chased him, calling “Stop Jew, don’t run away!”

Marx was found guilty on October 20, 1904. An appeal to the Connecticut Supreme Court arguing that the state didn’t produce sufficient evidence to convict and a special session of the state board of pardons were unsuccessful. Marx’s last words, spoken to the warden of the state prison in Wethersfield just before he was hanged at midnight on May 18, 1905, were “Don’t forget I always said I was innocent. Goodbye.” The charges against his wife were dropped soon after the execution.

Three years later Marx’s name resurfaced in the press in connection with a subsequent murder. On December 25, 1908, Hartford business owner Samuel Rodinsky was shot and killed. Police initially suspected “professional thugs.” But they discovered that Rodinsky’s wife had once claimed (but never actually received) the $1,100 reward offered by the State of Connecticut and the Town of Colchester for information leading to the capture of fugitive Gershom Marx. The Courant surmised that Rodinsky was “probably murdered because he betrayed [his]fellow countryman,” but no one was ever charged.

Three years later Marx’s name resurfaced in the press in connection with a subsequent murder. On December 25, 1908, Hartford business owner Samuel Rodinsky was shot and killed. Police initially suspected “professional thugs.” But they discovered that Rodinsky’s wife had once claimed (but never actually received) the $1,100 reward offered by the State of Connecticut and the Town of Colchester for information leading to the capture of fugitive Gershom Marx. The Courant surmised that Rodinsky was “probably murdered because he betrayed [his]fellow countryman,” but no one was ever charged.

Johnna Kaplan is a freelance writer and editor. She lives in New London and blogs about travel in Connecticut at thesizeofconnecticut.com.