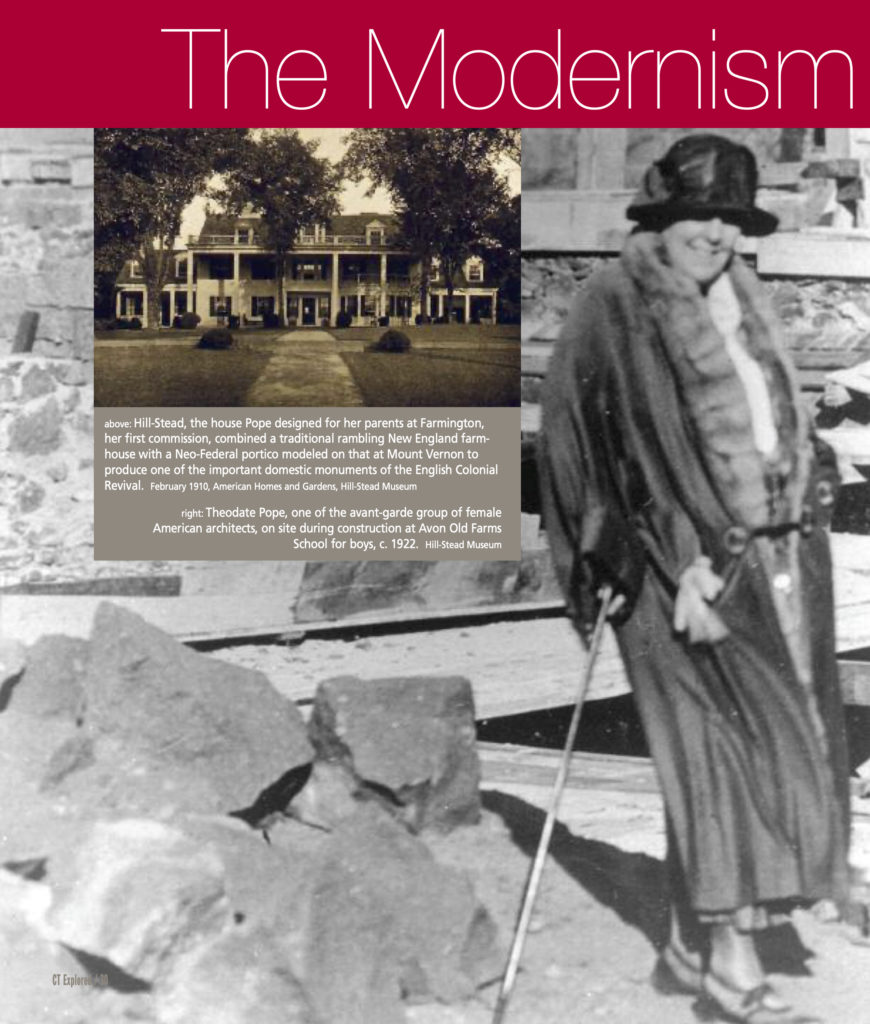

Theodate Pope, one of the avant-garde group of female American architects, on site during construction at Avon Old Farms School for boys, c. 1922. Hill-Stead Museum

By James F. O’Gorman

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2009/2010

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Modernism and Theodate Pope Riddle? The conjunction must sound odd to those who have heard of her reaction to the traveling exhibition of International Style Modern architecture that opened at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford in 1932. The display consisted of images of buildings with flat roofs, boxy shapes, large areas of glass, and smooth, bleached walls devoid of ornament. It declared a break with past historical styles. It showcased the works of the Franco-Swiss Modernist called Le Corbusier who had famously proclaimed a house a “machine for living in.”

Pope (hereafter I use her professional name) labeled the work on exhibition a failure because “it was purely intellectual without regard to the emotions,” because it ignored a basic human need. “Men who worked with machinery during the day might rather not sleep in a machine at night,” she told The Hartford Times. Her reaction was all the more remarkable because the show had been organized by her younger cousin, Philip Johnson, who would go on to become one of the superstars of International Style architecture. His famous Glass House at New Canaan remains a canonical image and also a landmark of mid-20th-century Modernism. [See “Philip Johnson’s 50-Year Experiment in Architecture and Landscape,” Winter 2019-2020 and “Philip Johnson in his Own Words,” Winter 2009-2010]

It might then indeed seem odd to include the work of Theodate Pope in an issue on Connecticut modernism. That stems largely from the lack of clarity about what is modern and what is Modern, the former indicating that one is in step with her times, the latter denoting a later movement in art and architecture. As of the early 20th century, Pope was up to date, having broken out of her Victorian upbringing as Effie Pope to emerge as thoroughly modern Theodate. She challenged the expectations of her family, the traditions of her social class, and the status quo of the male-dominated architectural profession to join the thin ranks of trailblazing women who fought for a footing in the practice, and she become a much-admired designer. In her time her work held its own with the leading contemporary building design in this country and in England. She never succumbed to the later International Style Modernism of her cousin, but she stood high in the ranks of the moderns of her own generation. This may be briefly demonstrated by looking beyond her best-known work, Hill-Stead, the early house in Farmington she designed for her parents, to consider some of her other Connecticut buildings, especially the Chamberlain house and the Westover and Avon Old Farms schools.

Born in Cleveland to wealth and privilege in 1867, the same year that brought Frank Lloyd Wright into the world, Pope grew into an independent, largely self-taught architect. She studied paintings and buildings on trips with her family to England and the Continent, was briefly tutored in design at Princeton, and rehabilitated a colonial house in Farmington. At age 31, encouraged by her father and with the manual help of draftsmen at the office of McKim, Mead and White in New York, she laid out Hill-Stead in the then fashionable style of the English Colonial Revival. The house is a combination of traditional rambling New England farmhouse and a high-style Mount Vernon portico. It shares its apparent patriotic roots with innumerable buildings of its age and indeed many since. But such stylistic references were purely iconographical; within the building’s traditional exterior were all the state-of-the-art conveniences of the comfortable home: plentiful plumbing, electricity, heating and ventilating, and an early system of cooling. As the critic Barr Ferree wrote in American Homes and Gardens in 1910, Hill-Stead “is at once scholarly and refined, modern and old.”

Pope’s first commission, as is so often the case with architects, stemmed from her family, and, as is also often the case, commissions for subsequent work continued to come from friends. But hers was a practice as professional as any other, conducted, even after her marriage to John Riddle in 1916, under her own family name. After Hill-Stead she opened an architectural office in New York in 1907, received a license to practice there in 1916, and in 1918 she was elected to the American Institute of Architects. (She wouldn’t be licensed to practice in Connecticut until 1933 – the first year that state granted architects licenses.) As a pioneering female architect, and one who did not need to work for a living, her list of realized buildings is not long. But it is choice, and punctuated with works admired by the severest of critics, her fellow (male) architects.

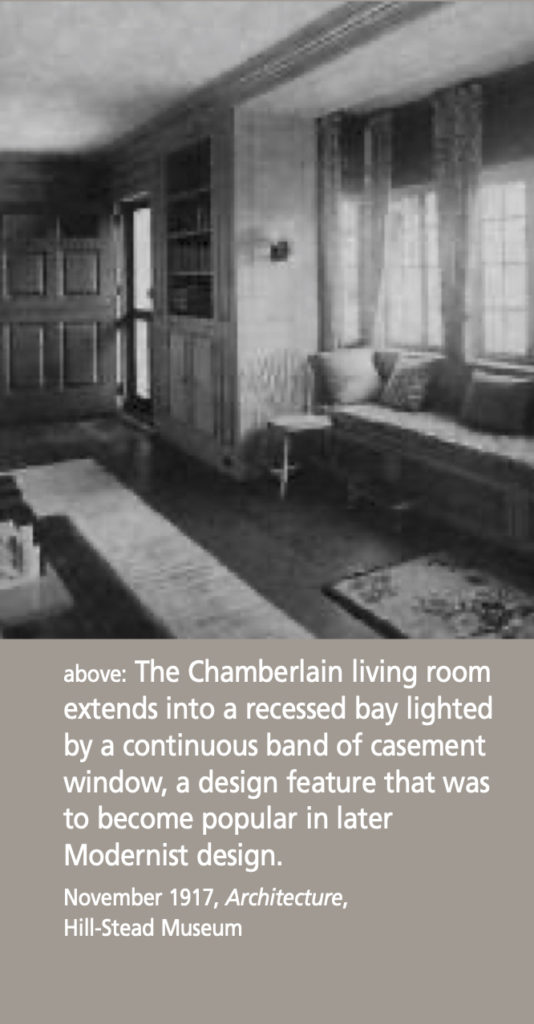

During her travels abroad, especially in 1910, Pope became enthralled with the domestic architecture, old and new, of Scotland and the Cotswolds, as well as the products of the contemporary, anti-industrial, English Arts and Crafts Movement. Her next house after Hill-Stead showed the results of this inclination. Little-known “Highfield,” the Joseph and Elizabeth Chamberlain house at Middlebury, which she created in 1911, reflects her interest in English contemporary domestic design as represented by the houses of the leader in the field, Charles Francis Annesley Voysey. I can find no record of her knowing the man personally, or of her touring any of his many houses, although she did visit one by his equally important contemporary, Edwin Lutyens. But Voysey’s work, seen as a precursor of Modernism in the 1930s, was well published at the turn of the century. The International Studio, much read in this country, regularly carried articles about his work and that of his like-minded colleagues. More importantly, still resting on a shelf in the library at Hill-Stead is Pope’s copy of The Modern Home: a Book of British Domestic Architecture for Moderate Incomes published in 1906. Many of the examples shown there, including two by Voysey, are small, at least by English peerage standards, and so were apt inspiration for residences of the American middle class. (Joseph Chamberlain was a professor of law at Columbia University.) Voysey typically produced two-story volumes covered with high-pitched roofs that swoop down to one-story stucco walls punctuated by grouped casement windows framed in stone. The volume is often enriched by dormers, orioles, gable ends, and tall sculpted chimneys terminating in terra cotta pots. Voysey’s own house, “The Orchard” in Hertforshire, (designed in 1899) is representative of the type, although his “Broadleys” of the previous year, dramatically sited overlooking Lake Windermere, or nearby “Moorcrag,” more subtly placed, are also suggestive comparisons.

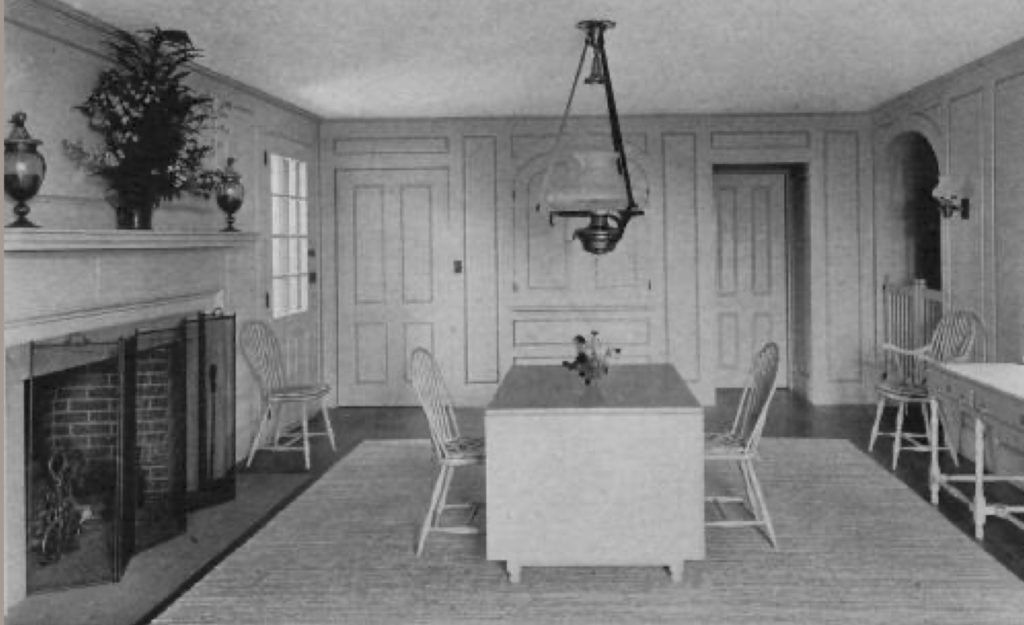

The Chamberlains acquired nearly 600 acres of land in Middlebury in 1909 and hired Warren Manning, a landscape architect known to Pope from his work at Hill-Stead, to site the house on high ground overlooking Lake Quassapaug. In designing Highfield Pope paid homage to modern English domestic design. The hallmarks of that work exist here but are simplified or translated into American materials. The windows, for example, are casements framed in wood rather than stone, but were originally painted yellow, perhaps to recall Voysey’s palette. The high gables, chimney pots, stucco walls, and oriole lighting the living room all echo contemporary English design. At 18 rooms and many baths the house is not small, but the plan, composed of additive units, rises into separate blocks that make the front volume look cottage-like. The thin interior details, on which Pope worked in early 1914, and the original simple furnishings, as we can see from early photographs and by examining the existing building, reflect the crisp lines of Voysey’s characteristic stair balusters and wall paneling. The summerhouse Pope designed for the garden adjacent to the reflecting pool follows the lead of the main house in the prominence of the roof and cozy fireplace, but Pope seems to have here achieved her own version of her cousin Philip’s later Glass House. She surrounded the interior of the pavilion with removable, glazed, floor-to-eaves doors. The estate is now owned by a golf club that retains the Highfield name.

The whiteness and geometric simplicity of the Chamberlain dining room rejects Victorian clutter and reflects in its simplicity Voysey’s contemporary work in England and anticipates Modernist interior design. November 1917, Architecture magazine, Hill-Stead Museum

Many of the first female architects became proficient designers of two building types representing areas of life with which women were thought to have a special affinity: domesticity and education. The bulk of Pope’s short list of buildings falls into these categories. Other than the houses just discussed her major works include two boarding schools in Connecticut, Westover Girls School in Middlebury and Avon Old Farms School for boys. Both remain vital educational institutions.

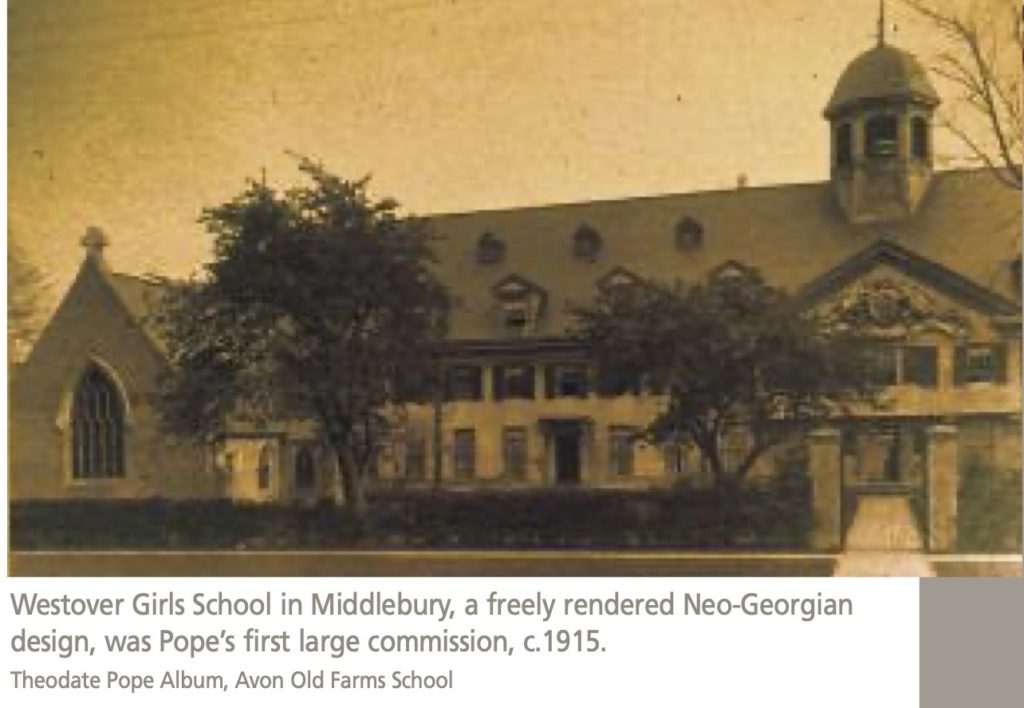

Westover followed quickly on the heels of Hill-Stead. Designed to house the pedagogical ideals of Pope’s friend, Mary Robbins Hillard, the project began to take shape in the two women’s minds in 1903; drawings created in 1906 led to construction between 1907 and 1909. At its completion the Architectural League of New York exhibited photographs of the complex. Cass Gilbert, among the most important architects of the period, called Westover “beautifully designed and beautifully planned.” He was not alone in his praise.

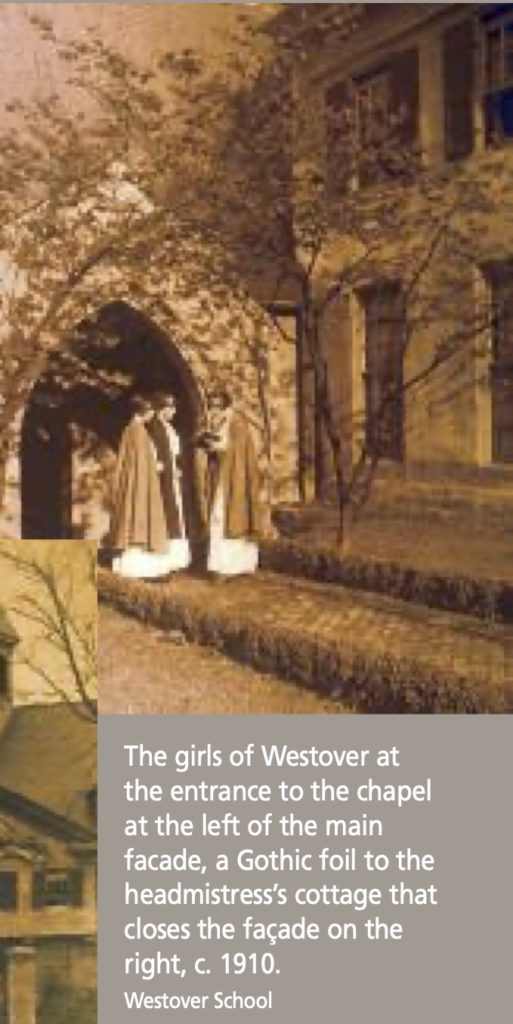

The square plan wraps around a traditional collegiate quadrangle articulated by a columnar arcade of three-centered arches. The 270-foot long, two-story main façade flattened beneath a steep roof faces the town green. It is embraced by a chapel on the left and the headmistress’s house on the right and is centered on an axis running up from the main entrance through the projecting ornamental pediment supported on brackets to the cupola riding the ridge of roof. A row of dormers lights the second story. In general the style is freely handled English Colonial with Gothic forms in the chapel and hints of contemporary British Arts and Crafts design inside. Pope’s independent thinking led her away from the rigid symmetry of so much of contemporary Colonial or Neo-Georgian work as she expressed the varied uses of the projecting end salients differently, the chapel lighted by a large Tudor window and entered through a pointed porch, the headmistress’s cottage with shuttered windows and small garden. It was a bold violation of classical decorum, but a move that enlivens the solid exterior ensemble.

Westover Girls School in Middlebury, a freely rendered Neo-Georgian design, was Pope’s first large commission, c. 1915. Theodate Pope Album, Avon Old Farms School

The wings of the building surrounding the quadrangle contain the entire program: library, gymnasium, dining hall, kitchen, assembly hall, classrooms, dorm rooms, and so forth. Within the visitor finds another stylistic change of pace, especially apparent in the dramatic “Red Hall,” the two-story main space surrounded by a balcony of walnut woodwork reached by twin flights of stairs at the end of the room. The piers of the balcony support transverse ceiling beams; this divides the volume into a cage of smaller visual units. There is a glancing resemblance here to then-current British design such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s interior at the Glasgow School of Art. It is next to impossible that Pope could have known of this work, even through publications, because the library of the art school is contemporary with Red Hall, but her affinity with English Arts and Crafts ideals underlies this modern space. She also designed much of the original furniture.

Students at the entrance to the Westover school chapel at the left of the main facade, a Gothic foil to the headmistress’s cottage that closes the façade on the right, c. 1910. Westover School

Pope’s pursuit of pedagogical form, both in program and in building, led her eventually to conceive of a model preparatory school for boys that became Avon Old Farms. For this she was her own client. Having consulted the most important educators of the day, and Columbia University philosopher John Dewey, about contemporary ideals for educational curricula, by 1918 she was ready to begin the last great work of her life. Like Thomas Jefferson at the University of Virginia, Theodate formulated an ideal educational program for her school and then embodied it in an architectural masterpiece that reflected that program. To Dewey’s “learn by doing” she welded John Ruskin’s and the Arts and Crafts ideal of handwork in the teachings of the school and the buildings that housed it. It was to be a place where work at gardening or husbandry, in the forge or woodworking and printing shops, would be an integral part of the learning process. Here form and function would be one, for the students would be surrounded by the physical manifestation of their aims, a handmade environment designed by an architect progressive in her educational aims and her Arts and Crafts inspiration, however anti-Modern in her rejection of machine technology and machine imagery.

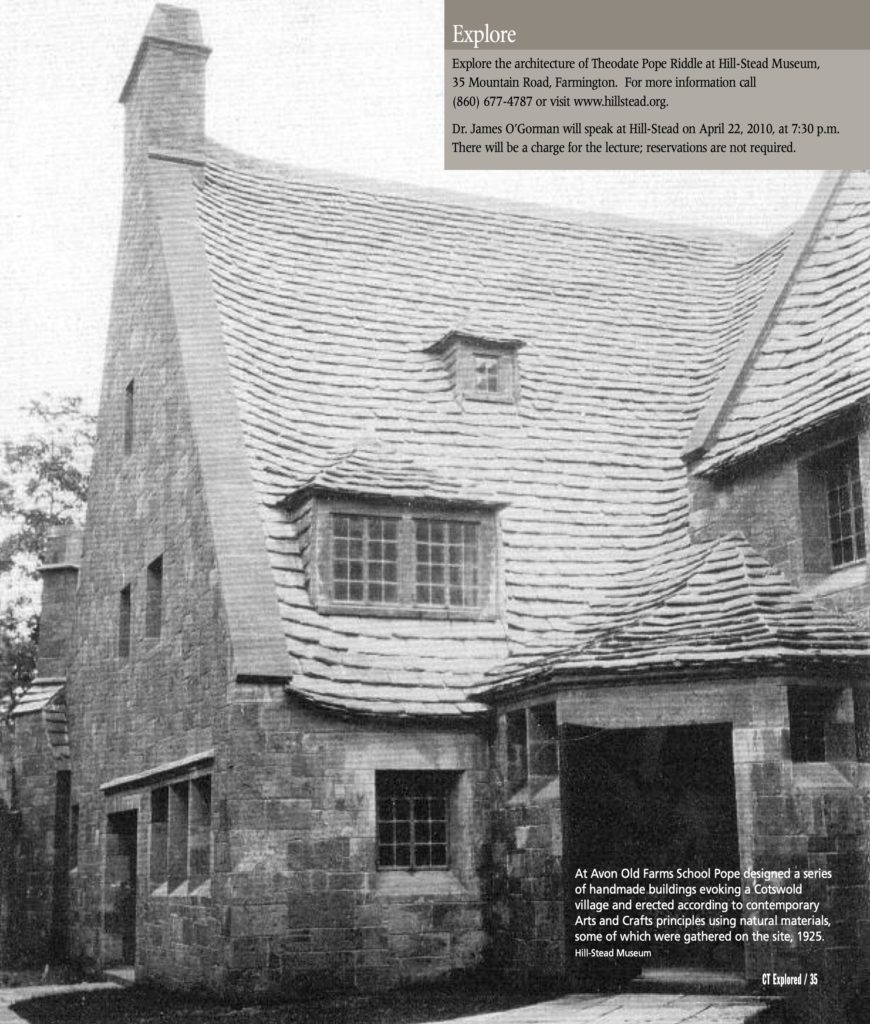

Like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin in Wisconsin, it too an Arts and Crafts-inspired educational community, Pope’s Avon Old Farms grew and changed over the years. What began on paper as two traditional academic courtyards in the event shrank to one. Drawing on her first-hand knowledge of traditional and contemporary English work, as well as her own library of books on the subject, she designed a series of buildings evoking a Cotswold village erected according to Arts and Crafts principles. They would be hand wrought using natural materials, some gathered on the site, put in place by imported English workmen or locals trained by them. In the architect’s words, these men were to “dispense with all mechanical methods” of building, “and wherever possible, use old tools and processes.” They were instructed “to work by rule of thumb and to gauge all verticals by sight; as a natural variation in line and surface was far more desirable in this work than accuracy.” She prohibited the use of levels or plumb rules and dictated that the walls be laid up by eye. The energized forms of Avon’s buildings stand as the visual result of this handmade process.

Although Pope’s vision for Avon outpaced her ability to build it in a worsening economic climate, and construction effectively stopped during the Depression, she left many drawings of unrealized projects to show her complete intentions. These, together with what was accomplished in her lifetime, show an “academical village” (to borrow Jefferson’s description of his ideal educational institution) largely composed of irregular plastic shapes in contrast to the rigid lines of machine-made forms, of steep swooping slate roofs with wobbly ridges, irregularly placed dormers, fanciful orioles, massive sculpted chimneys, textured stone or brick walls, and hewn wooden details. Interiors are warm and cozy by design. It seems a complex that grew and changed over time—as indeed it did—from the massive cylindrical water tower near the entrance to the Doric bank at the rear, contrasting in geometry to the lively, free-hand shapes in between. Pope’s attack on the International Style architecture she saw at Hartford in 1932 came five years after her unfinished school at Avon opened its doors to its first students. What she viewed at the exhibition ran counter to everything she had aimed to accomplish in her work, but that aim was anti-Modern rather than anti-modern; it confronted that part of the world of design in which a machine esthetic ruled all. In terms of the way American architectural history of the 20th century has been written, in which a series of mechanistic buildings created by rejecting the legacy of the past muscles out all other work, Pope’s career seems an anomaly. But the International Style was just one manifestation of the architecture of the period. The buildings of the early 20th century exhibit hand-wrought as well as machine-made characteristics, period as well as Modern design. No adequate assessment of the era’s architecture can omit work such as the modern Gothic of Ralph Adams Cram (who with his partner Bertram Goodhue designed the church of St. Thomas in Manhattan in 1909) or the modern classicism of Paul Phillippe Cret (who designed the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D. C. in 1929). A true picture of the era must embrace a wide diversity of au courant work. When it is limned, Theodate Pope’s major buildings will find their rightful place.

At Avon Old Farms School Pope designed a series of handmade buildings evoking a Cotswold village and erected according to contemporary Arts and Crafts principles using natural materials, some of which were gathered on the site, 1925. Hill-Stead Museum

James F. O’Gorman is professor emeritus of the history of American art at Wellesley College and editor of a forthcoming book on the Hill-Stead Museum designed by Theodate Pope.

Explore!

Read more about Connecticut’s architecture and historic preservation and art history on our TOPICS page.

Read more about Hill-Stead in “Hill-Stead: A Colonial Revival Performance,” and about its art collection.