(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2018

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1963 a young business professional and avid golfer named Gerard “Gerry” M. Peterson sought membership in the Keney Park Golf Club at the municipal course in Keney Park in Hartford. He was refused the opportunity to submit an application. The club, he was told, didn’t need any more members.

Peterson was a rising star at Aetna Life and Casualty, with a B.A. in economics from the University of Connecticut (1957). He had grown up in Hartford’s South End, playing golf as a member of the Bulkeley High School golf team. When he was a sophomore, he and his teammates were asked to join the Goodwin Park Golf Club, and in 1948 he had secured his Connecticut State Golfers Association (CSGA) handicap card, providing him access to amateur golf tournaments across the state.

Years later, after a stint in the United States Army and completion of college, Peterson relocated to the North End and was ready to update his CSGA card at the course in nearby Keney Park so that he could play in amateur CSGA-sanctioned tournaments. As president of Keney Park’s Midway Golf Club, he should have been an excellent candidate for admittance to the one CSGA-recognized club there. But Peterson was black.

After World War I the first Great Migration saw an increase in Hartford’s black population, which began to cluster in the North End. Life in cities like Hartford was far less hostile and restrictive than in the South, but African Americans who relocated to Connecticut found themselves constrained by conditions of racial prejudice and a semi-segregated society.

Golf got its start in the U.S. in the 1890s in private country clubs that did not accept African Americans as members. The Professional Golfers Association of America (PGA), formed in 1916, maintained a “Caucasian-clause” within its by-laws from 1934 until 1961, restricting access to competition and prize money for black players in nearly every professional tournament in the country. Many future black golf professionals such as Charlie Sifford, Ted Rhodes, and Lee Elder developed their passion for the game as young caddies watching the techniques of white players.

Beginning in the 1920s African Americans formed their own golf organizations. During the next two decades, new clubs organized in Los Angeles, Miami, Houston, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Indianapolis, Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis, and Atlanta and regionally in Providence, Boston, Albany, Bridgeport, Springfield, New Britain, Hartford, and New Haven.

Frustrated by the PGA’s Caucasian clause, affluent black businessmen in Washington, D.C. formed the United Golfers Association in 1925. The UGA operated its own tournaments, which rivaled the excitement of PGA events. From 1926 until 1962, the UGA Negro National Open Championship was an annual affair for professional black men and women golfers across the country. Only after Charlie Sifford directly challenged the PGA in 1960, assisted by California Attorney General Stanley Mosk, did the PGA begin to loosen its restrictions and allow Sifford and others to compete in PGA-sponsored tournaments. Although past his prime playing years by then, Sifford won the Greater Hartford Open in 1967.

Keney Park Golf Course opened its first nine holes in 1927 and the second nine in 1930, and by 1934 the organization had completed work on a Tudor Revival-style clubhouse, constructed by WPA labor with stone salvaged from the old Hartford Post Office. In 1936, 52,824 rounds of golf were played there. Black golfers shared the course, clubhouse, and locker rooms, but they mostly competed in separate tournaments.

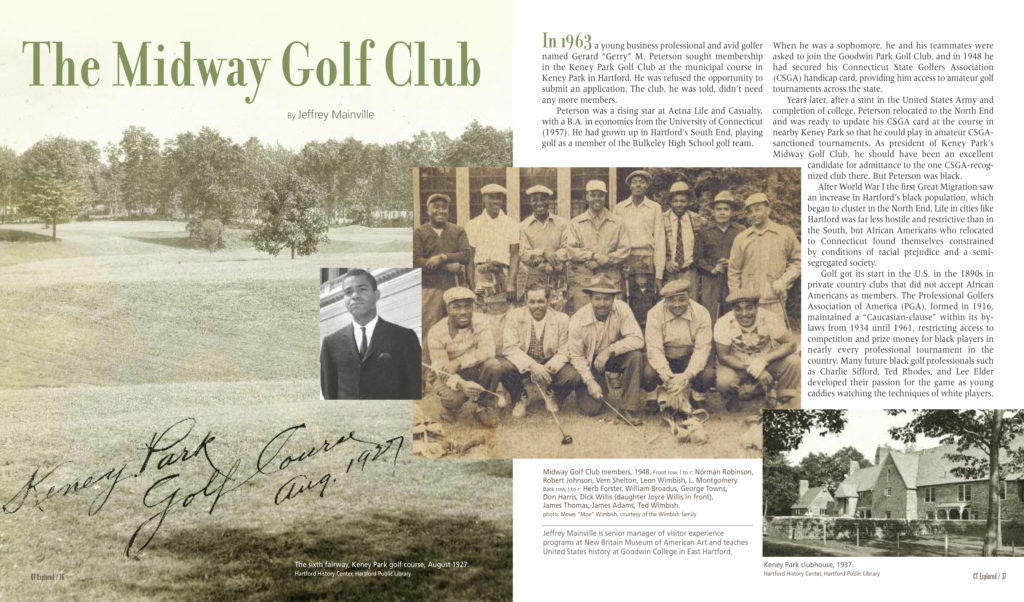

As early as September 16, 1933, African Americans competed in the Southern New England Colored Golf Championship at Keney Park. Prizes were displayed in advance at Henry Williams’s barbershop at 1978 Main Street. The Midway Golf Club formed some time between 1927 and 1933 at Keney Park and provided the opportunity for Hartford-area golfers of color to enjoy the sport. Sifford competed in (and won) many tournaments at Keney Park in the 1950s, and Lee Elder played there in 1961.

Midway took great pride in its annual Metropolitan Junior Tournament, which began in 1960 and drew 393 participants by 1962. Led by Director Vernon Shelton, the Junior Tournament welcomed all golfers, regardless of color. Kids from Glastonbury and Avon competed against kids from Hartford and Bloomfield. The Midway group paid for the young golfers’ greens fees and lunches.

Midway hosted a Labor Day Tournament in 1967 with the purpose of creating a scholarship fund to help send inner-city kids to college. Trophies for the winners were donated by Wilfred X. Johnson, former member of the Connecticut General Assembly. Midway men like “Slim” Willis, Vernon Shelton, Herb Foster, Rubin Brown, Henderson “Sonny” Duval, Dave Pernell, Leon Wimbish, Moses Wimbish, and Ted Wimbish helped mentor young golfers and promote the sport.

On August 28, 1963, as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his historic speech to the tens of thousands gathered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Gerry Peterson, president of the Midway Golf Club, was handing a trophy to Prosper Vignone of Farmington, winner of the 4thAnnual Midway Junior Tournament. Days later, the club decided that Peterson would submit an application to the Keney Park Golf Club. After he was rejected, Peterson contacted Hartford City Manager Elisha Freedman.

Freedman wrote to the Keney Park Golf Club to ask if they were openly discriminating against an African American by denying Peterson’s membership, implying that the rejection was made because of his race. The city manager also saw to it that the dispute was publicized in The Hartford Courant and by December had appealed to the city council for help in taking action against the club. He explained, “Because the CSGA recognizes only one club per golf course, in order for the complainant to gain CSGA membership he must be a member of the Keney Park Golf club, the organization recognized by the CSGA. The Keney Park Club is an all-white group.”

Freedman further explained that he recognized that the city could not force a private organization to “take a member that it does not want.” However, he pointed out that “the City is providing the means by which the Keney Park Golf Club can claim CSGA membership, namely, a publicly owned and operated golf course. We feel that all citizens of the City should be able to enjoy the same privileges which play at a City run course provides. … After all, both the Midway Golf Club members and Keney Park Golf Club members share the same lockers, the same showers, the same turf and the same free City air.”

Freedman also noted that he had first proposed to the CSGA that it recognize more than one club per golf course or allow the city to hold the CSGA membership, but the CSGA refused on the grounds that it would violate its rules. He recommended that “the city council arrange a meeting with the [Keney Park Golf] club to seek its cooperation, and if such cooperation is not obtained by the first of the year, that the city revoke its recognition of the club and withdraw club privileges at the course.” The Hartford City Council agreed, and after the January 1 deadline, the Keney Park Golf Club voted to accept Peterson and abandoned its resistance to the compliance order.

Peterson and the Midway Golf Club were part of a larger national struggle during the civil rights era in America. By 1964 the fight to end racial discrimination at municipal golf courses in America was largely won, and federal passage of the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965) was soon to follow. But rather than embracing racial integration, many white golfers chose to move on and form other golf clubs in the suburbs.

Decades later, Midway golfer Dave Pernell expressed a debt of gratitude to Peterson:

I was the first black professional that ever won the Connecticut Senior Open … and I was the first black that ever won the New England Senior Open. I turned pro in 1973. [Gerry] opened a lot of doors. He was one of the guys who wanted [discrimination]to end and we all appreciated it. We are all very grateful … and especially me, I’m very grateful to him.

Peterson explained in an interview with me in 2011,

Golf for me has been the reason I am where I am today. There is no doubt in my mind that caddying at the country club and learning about the lifestyles of the rich and famous, being accepted as somebody that could play the game and knew the game … eventually working for the United States Golf Association as a rules official, and for their Senior Amateur Championship for thirteen years … golf has been my life … and it has changed my life dramatically.

For his dedication to the game, exceptional skill as a player, and extraordinary efforts to promote the advancement of African Americans in the sport, Peterson was inducted into the Black Golf Hall of Fame on June 6, 2015, at a ceremony in St. Augustine, Florida.

Jeffrey Mainville is senior manager of visitor experience programs at New Britain Museum of American Art and teaches United States history at Goodwin College in East Hartford.

Episode 57: Grating the Nutmeg podcast with Gerry Peterson and Jeffrey Mainville