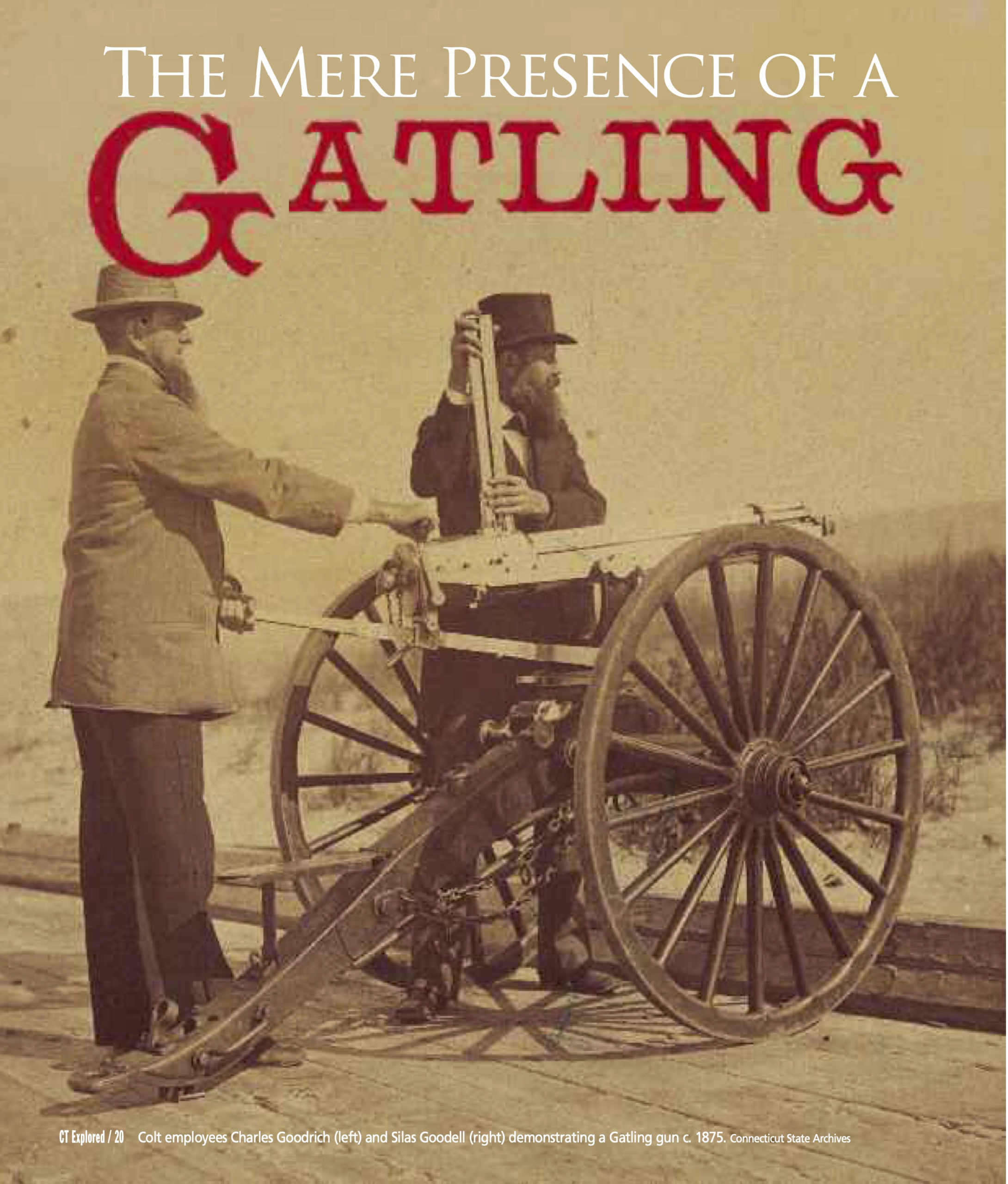

Colt employees Charles Goodrich (left) and Silas Goodell (right) demonstrating a Gatling gun c. 1875. Connecticut State Archives

By David Corrigan

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2013/2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

“TROOPS IN WATERBURY. Sixteen Infantry Companies, Two Gatlings,” read The Hartford Courant headline on February 1, 1903. In response to a request from Waterbury Mayor Edward G. Kilduff, Governor Abiram Chamberlain had activated nearly 900 Connecticut National Guardsmen to help local authorities contain violence arising from a strike by 80 motormen and conductors against the Connecticut Railway and Lighting Company.

The strike began on January 11 and was prompted by the company’s firing of four members of the Amalgamated Association of Street Railway Employees union. By January 15, the railway company had imported nearly 90 strikebreakers to run the trolleys. Waterbury residents responded with a boycott, refusing to ride the cars. On the night of January 16, a crowd of 500 broke windows in the company’s car barn, while police kept a safe distance away. As historian A.J. Scopino Jr. notes in “Community, Class and Conflict: The Waterbury Trolley Strike of 1903” (Connecticut History, March 1983), “Leniency and restraint marked police reaction to the stone throwers and other demonstrations of strike support. Generally sympathetic to the strike and often too outnumbered to be effective during confrontations between strike sympathizers and strikebreakers, the police regularly overlooked acts of lawlessness at the company’s expense.”

For the next two weeks, stone throwing and the breaking of trolley-car windows continued. Violence suddenly escalated on the night of January 31. Two strikebreakers operating a car opened fire on a crowd of strikers and sympathizers estimated at 5,000 strong, and the throngs descended on them. One motorman was taken from the trolley car and beaten unconscious, amid threats to hang him. Waterbury police intervened and rescued the man, but they were unable to control the protesters. Mayor Kilduff tried to address the crowd but was drowned out and, realizing neither he nor the police would be able to restore order, reluctantly called for aid from Gov. Chamberlain early on the morning of February 1.

As the state’s commander-in-chief, Chamberlain ordered two Waterbury infantry companies of the Second Regiment to report to the Waterbury armory at 6 p.m. Nine infantry companies and the Gatling gun section from Hartford’s First Regiment embarked by train for Waterbury, joined by one company from New Britain and one from Bristol. Arriving in Waterbury around 9:30 that night, they were joined by five companies and the Gatling gun section from New Haven’s Second Regiment a half-hour later.

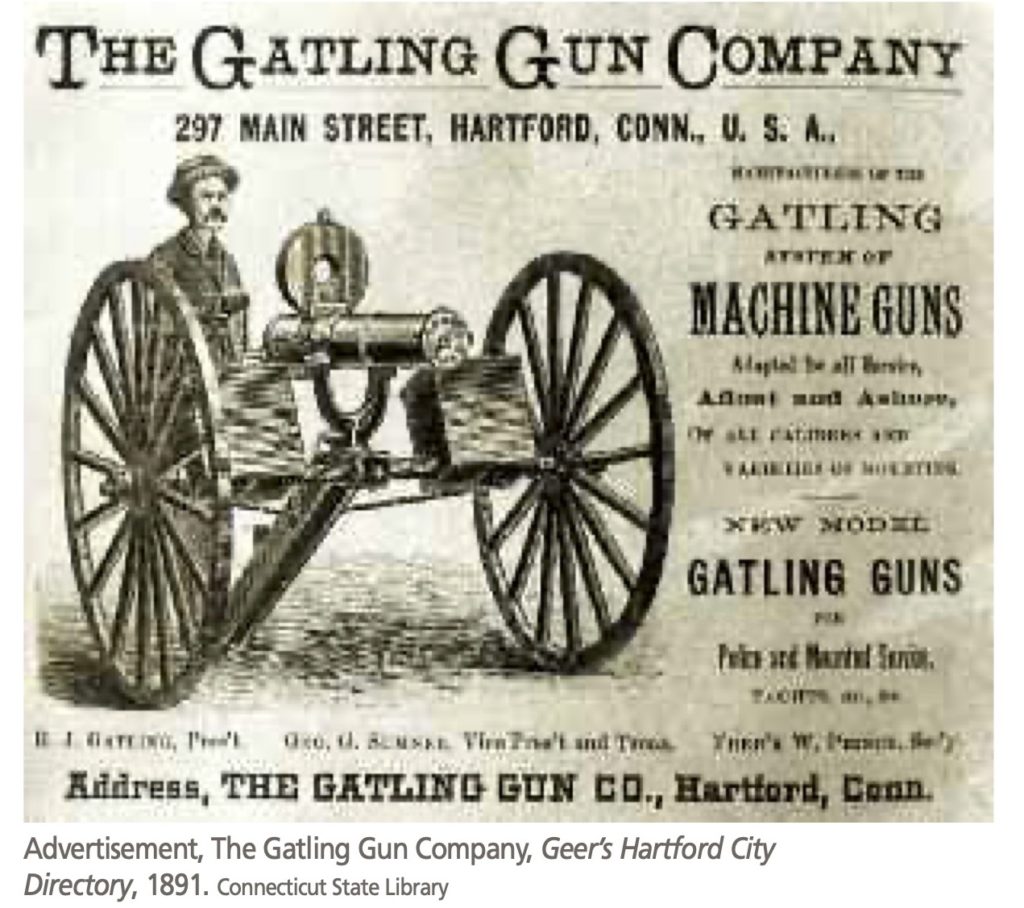

Advertisement, The Gatling Gun Company, Geer’s Hartford City Directory, 1891. Connecticut State Library

Connecticut was home to The Gatling Gun Company, a division of Colt’s Fire Arms Manufacturing Company of Hartford that turned out thousands of these lethal “machine guns”—the first effective weapons of their kind—between 1866 and 1911. Conceived as a field weapon, the Gatling employed multiple rotating barrels, which fired independently when turned by a hand crank. As the barrels rotated, each automatically loaded a cartridge, fired, discharged the empty cartridge, and reloaded. Early Gatling guns could fire 200 rounds per minute. Though not an automatic weapon, the Gatling, as the first successful machine gun, paved the way for fully automatic weapons in the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

Given the violence characterizing relations between labor and management in late 19th- and early 20th-century America, Chamberlain’s decision to send Gatling gun-equipped National Guard troops to Waterbury in 1903 may not seem remarkable. Labor unions in Connecticut had increased in number from 138 in 1898 to 591 in 1903, and the number of labor disturbances had risen from 54 in 1900 to 104 in 1902. Conditions were increasingly ripe for labor protest in the state –and ample means of suppressing protest lay readily at hand. But Chamberlain’s National Guard call-up was the first in the history of the state, and while the Connecticut National Guard had been equipped with Gatling guns since the 1870s, not one had ever been deployed here.

Nor would they be deployed on this occasion. On February 3, The Courant reported that the New York Journal “had it that (the) machine guns were trained for action—that (the) railroad company may try to break (the) strike.” But The Courant tersely reported, “The machine guns are in the armory basement.” And there they stayed during the Guard’s four-day deployment.

Chamberlain’s motives in dispatching the National Guardsmen and the Gatling guns to Waterbury did not include supporting the railway company and its strikebreakers; he was trying to keep the peace. He explained to The Courant: “The mayor thought we had sent more troops than necessary but I told him I didn’t think so. When it came up to the state to act I proposed to do so in a way that would have a strong moral effect. While we didn’t send the troops there to kill anyone it would have been useless to send a company or two there.” The Courant also reported, “The governor’s desire was that there should be ample number to settle matters as quickly as possible and to show the power of the state.” (The Hartford Courant, February 3, 1903)

Historian Julia Keller, in Mr. Gatling’s Terrible Marvel (Penguin Books, 2008) has written about the cultural significance of the Gatling gun. “Gatling guns,” she notes, “were a coolly efficient way of demonstrating that the men in charge meant business. Even if it wasn’t fired, a Gatling gun made a powerful statement…. (It) was like a ‘Beware of Dog’ notice. It made potential troublemakers hesitate, then back away…. (The guns were seen) as menacing symbols, as icons of sheer destructive ferocity, even if they just sat there.”

The symbolic power of the Gatling gun became evident early in its history. In July 1863, at the height of the Civil War Draft Riots in New York City, Henry Jarvis Raymond, a founder and owner of The New York Times and a supporter of President Lincoln and the Conscription Act passed in March of that year, mounted three Gatling guns in windows and on the roof of the newspaper’s office to deter rioters from attacking the building. According to Keller “…it was not only military men but also police officers and wealthy private citizens who desired (Gatling guns). By the 1870s, mine owners and railroad tycoons had discovered that Gatling guns came in handy for keeping discontented workers in line….”

The Gatling Gun Company marketed its product accordingly. During the Railroad Strike of 1877, which engulfed western Pennsylvania and the Midwest, Edgar T. Welles, son of Glastonbury native and former Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, and the manager of the Gatling Gun Company, wrote to John W. Garrett, president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company, which was a primary target of striking workers:

The recent riotous disturbances throughout the country have shown the necessity of preparation by such confrontations as the one over which you preside, to meet violence by superior force and skill. The calls made upon us during the existence of the riots were too sudden to be promptly met, and we have the honor to suggest that you strengthen yourselves now against such emergencies in the future, by providing yourselves with Gatling guns. The reputation, character and effectiveness of the gun, are too well known to be repeated. Four or five men only are required to operate it, and one Gatling with a full supply of ammunition, can clear a street or track, and keep it clear. Hence, a few tried employees supplied with Gatlings, afford a Railroad Company a perfect means of defense within itself.

Welles apologized that the company was unable to keep up with the demand for the guns, and his statement that a “…few tried employees…can clear a street or track, and keep it clear,” is an early example of aggressive rhetoric that may have implied, but did not specify, that “tried” men actually would have to fire at striking workers to achieve their goal. Even in the most violent of 19th-century labor uprisings—The Railroad Strike of 1877, Haymarket in 1886, the Homestead Strike of 1892, and the Pullman Strike of 1894—Gatling guns, when used, were typically wheeled into place in the face of striking workers but not fired.

Of course, that wasn’t always the case. Keller notes, “A half dozen times between 1874 and 1878, Gatling guns were fired at Native Americans who resisted the takeover of their homelands.” Beginning in the 1860s and continuing through the end of the century, the Gatling Gun Company also supplied many foreign governments with their weapons. According to The Hartford Courant (November 12, 1873), “There have been manufactured at the Colt works more than a thousand of these guns already, and a government contract and some state orders are now being filled…. Already several foreign powers, including England, Russia, Prussia and Austria, have it in use.” Historian Robert L. O’Connell maintains in Of Arms and Men: A History of War, Weapons and Aggression (Oxford University Press, 1989) that the Gatling gun was popular with British colonial forces because “…from an imperialist standpoint, the machine gun was nearly the perfect laborsaving device, enabling tiny forces of whites to mow down multitudes of brave but thoroughly outgunned native warriors.”

Hartford’s police patrol wagon #1 with Model 1893 Bulldog Gatling gun, c. 1893. Connecticut State Archives

One reason the Gatling gun was never actually fired during a labor disturbance was the fact that many members of the National Guard were also members of labor unions or relatives of union members and thus were reluctant to fire upon fellow union members or family members. In Waterbury, Edward Maloney, one of the striking trolley men, was also a member of Waterbury’s Company G, Second Regiment. He was one of the first soldiers to respond to the governor’s order for his company to report to the local armory. An unidentified corporal from Company G, First Regiment was quoted as saying, “I am president of the Velvet Workers’ Union of Manchester which went out on a strike last June (and) about half of my company are members of unions in Manchester.” Several other officers and men from this company, as The Courant reported, “met relatives while at the Brass City, some of whom were among the striking trolley men.” (February 4 and 6, 1903)

With calm restored, on February 6 the Connecticut National Guard troops left Waterbury, returned to their home armories, and were discharged from their duty. The trolley men continued their strike, with sporadic violence and waning public support. The strike finally ended on August 10, with the railway company agreeing to a 10-hour day but refusing to recognize the Amalgamated Association of Street Railway Employees union or grant a wage hike. The deployment of National Guard troops had been short and seemingly uneventful. Yet the Guard presence, and especially the presence of Gatling guns, in Waterbury proved to have serious repercussions.

Two years later, in April 1905, representatives of more than 50 of Bridgeport’s largest manufacturers, with recent events in Waterbury still fresh in their minds, signed a petition to the Connecticut General Assembly requesting reestablishment of the Gatling gun unit at the Bridgeport armory. The unit had been disbanded when it failed to meet the standards established by the federal Militia Act of 1903, which defined the role of the National Guard in relation to the United States Army and provided for weapons and training upgrades. The 1905 petition stated, “We firmly believe that such an organization is absolutely needed in this city…. Bridgeport is the second largest manufacturing city in the state with thousands of skilled and unskilled workmen. Their prosperity and that of this city and state depends [sic]upon law and order. Riots and disorders here would seriously interfere with and jeopardize permanent and valuable vested rights and interests. Even the atmosphere in this city of a Machine Gun Battery adds to the welfare and security of our citizens.”

The petitioning manufacturers argued for two Gatlings, fully understanding their power to intimidate strikers into quickly ending any labor actions. Testimony before the legislature’s Military Affairs Committee in favor of the petition expanded upon this theme. A Mr. McGovern, a reporter for the Bridgeport Farmer, baldly stated, “This petition is primarily a manufacturer’s petition and should not require any explanation on the part of anyone in Bridgeport….” State Senator Allan W. Paige of Bridgeport testified, “We wish this established for the purpose of protecting the interests of Bridgeport if occasion should arise. If this should be established we want it manned with men of the understanding and knowledge and the natural inclination to carry out the duties they are there for.” Paige, a director of the Connecticut Railway and Lighting Company, also served as its general counsel and director of several other railway companies. As if to allay Paige’s concerns, Connecticut Adjutant General George Cole said he was in favor of returning the guns to Bridgeport, noting that he understood “…that there is a young man in Bridgeport of very excellent standing in military education who is ready to take hold of this” and that he “…is drawing three or four thousand dollars salary in a permanent position and… will get men of like character on those guns.” Yet an unidentified reporter from the Bridgeport Standard testified, “It is not necessary to turn the gun on a mob but the mere presence of a gun manned by competent men and officers would act as a restraining force itself.”

The Bridgeport Standard reporter noted the nature of the work force in the petitioning manufacturers’ factories: “… All of that labor isn’t skilled by any means. It is the labor that would be easily controlled by the mob spirit…. and with the general class of workingmen in Bridgeport in the large mills the tendency is to rapidly form mobs where they think there is any reason for it, and with a machine gun in Bridgeport it could be very quickly quelled.” Unspoken in the testimony was the fact that most of the unskilled factory workers in Bridgeport were recent immigrants performing the most menial, back-breaking industrial jobs under often intolerable conditions. Yet their tendency to form “mobs” apparently was regarded as unrelated to their working conditions. The reporter concluded, “It is of benefit to the city and to the state that these manufactures [sic]should be protected, not alone from those actually threatened but from any tendency that might arise and disturb them.”

The legislature restored the Gatling gun unit to Bridgeport, but Sen. Paige’s vision of the role of National Guard-manned Gatling guns (“to carry out the duties they are there for”) may have differed from Adjutant General Cole’s. Cole’s reference to a “young man … of very excellent standing in military education” seems to refer to a soldier aware of the chain of command and the need to follow orders once given. Evidence suggests that those orders would be to hold fire. On February 1, 1903, The Hartford Courant reported that, on the train to Waterbury, Col. Edward Schulze, commander of the National Guard troops, had cautioned the company captains against “any hasty action” and had instructed them “… not to fire without orders from (him), then to fire low, so as to wound rather than kill.” He also ordered his men “not to resent abuse, profane language or brickbats if thrown and to use only lead and cold steel when ordered.” According to The Courant, Col. Schulze had “his men well in hand.”

Although it is unclear exactly what level of provocation would have prompted the National Guard to wheel out and fire the Gatling guns, the fact that the guns stayed inside the Waterbury armory during the four days the Guard was on duty suggests that neither Gov. Chamberlain, Gen. Cole, nor Col. Schulze saw their use as an option in 1903, and they probably would have disappointed Sen. Paige in 1905 had a similar situation arisen in Bridgeport. It was enough that the guns were there.

David Corrigan is curator of the Museum of Connecticut History, a member of the CT Explored editorial team, and a frequent contributor to the magazine.