By Mark H. Jones WINTER 2011/12

By the mid-20th century, Frederic Collin Walcott was a familiar politician and state government official, having served as a United States senator from Connecticut from 1929 to 1935. But his greatest claim to fame was his work with Herbert Hoover during World War I to bring relief to the hungry refugees of Belgium and Poland. When he began that work in 1915, he was 46 and a successful Wall Street banker. His later life would be transformed by public service, which began with his work with Hoover to fight hunger in a Europe wracked by war.

By the mid-20th century, Frederic Collin Walcott was a familiar politician and state government official, having served as a United States senator from Connecticut from 1929 to 1935. But his greatest claim to fame was his work with Herbert Hoover during World War I to bring relief to the hungry refugees of Belgium and Poland. When he began that work in 1915, he was 46 and a successful Wall Street banker. His later life would be transformed by public service, which began with his work with Hoover to fight hunger in a Europe wracked by war.

Frederic Collin Walcott was born into privilege and wealth in 1869 in New York Mills, New York, just outside of Utica. In the early 1800s, Walcott’s grandfather established the first cotton mill in New York State. Walcott’s connection to Connecticut was through his mother, a member of the Welch family of Norfolk. Several generations of Welches had gone to Yale and become doctors.

Walcott also attended Yale, graduating in 1891. He took a world tour with a cousin from 1891 to 1892 and returned to work in his father’s mill, eventually sitting on the board of directors and serving as superintendent of the mill. His life was not without tragedy. In 1899 he married Frances Dana Archbold, daughter of the founder of Standard Oil. She died of a fever on their honeymoon cruise in Yokohoma, Japan. In 1905, Walcott inherited the textile works. That year was decisive for him. He sold the mill, married Mary Guthrie Hussey and moved with her to New York City.

He had come to New York at the urging of Starling Childs, a friend he met at Yale. Childs, with whom Walcott would remain close throughout his life, was a lawyer working at the William P. Bonbright & Company, a bank that invested in hydroelectric projects around the world and that supported the creation of the General Electric Company. Walcott’s friend may have convinced him he could make money in investment banking.

Walcott was indeed a success. In 1907, the first of the big trust banks in New York, the Knickerbocker Trust, failed. Through the influence of Childs and GE founder Charles Coffin, Walcott was appointed to a reorganization committeeto reopen the bank. In 1908, Walcott became a vice president there. In 1911 he left the Knickerbocker to become vice president at Bonbright & Company.

When World War I began in 1914, Walcott was 45. Like the rest of America, Walcott followed the course of the war through newspapers, gossip, and letters from English friends serving in combat. He sensed that the conflict would have a lasting effect on everyone, writing that the war would “present all manner of interesting problems and everyone of us that is left will have greater opportunities than ever for usefulness.”

Under President Woodrow Wilson, the United States remained neutral at the outset of the war, but American companies still conducted business with the allies. In 1915, Bonbright & Company began negotiations with French government officials and bankers on a massive, three-month loan that would allow the French to buy war-related materials from the United States. When French officials came to New York, Walcott sat in on the talks.

Bonbright & Company designated Walcott as its representative to negotiate war loans with both Italy and France and sent him to Europe. On November 8, 1915, he left New York. In long letters to his wife, who had stayed home with their two sons because she felt the trip would be too risky, Walcott described everything from hotels that he stayed at to conversations he had at receptions.

Walcott observed that the war had “purged” France and revived the spirit of the nation. The French were working together as never before, he noted. Everyone, even the wounded, had tasks in the war effort. He visited hospitals for wounded servicemen and saw women of the elite classes serving there. Walcott described the wounded in horrific detail, and he gave each wounded soldier he encountered some money; he also adopted an American field hospital.

At a train station in Berne, Walcott saw “stirring scenes.” There were around “150 soldiers returning to the front line after 4 or 6 days leave with their families—one legged, one armed and sightless comrades, wives, sisters and sweethearts to see them off, knowing that 50% of them would never return,” he wrote. “I shall never forget,” Walcott continued, “the courage that those women showed, not a tear, not a cheer—nothing to stir the emotions. The gloom of it all, the cold, grey, damp night, the lights all dimmed suggested a Godless world and forced smiles of these plucky women made me feel decidedly chokey.”

In Rome Walcott met with government officials and financiers and spent a Sunday sightseeing. He expected to head back to England and then take a ship to New York, but on the night of December 6, 1915, he “received a sudden awakening” by a cable from New York saying that John D. Rockefeller Jr. was asking him to become an agent for the Rockefeller Foundation to investigate the conditions of refugees in German-held Belgium. The Foundation was prepared to give generously to feed and clothe the Belgians, but Rockefeller wanted Walcott “to spend 2 weeks there at once to investigate for the Rockefeller Foundation and report what I thought they should do about sending money.” Walcott placed the cablegram in his diary, where it remains to this day.

The Foundation also asked Walcott to meet and evaluate Herbert Hoover, who had organized the Commission for Relief in Belgium in 1914 and evaluate his organization. Hoover was 40 and enjoyed wealth and a reputation as one of the most successful engineers in the world. In 1915, Walcott was a 46-year-old, successful international investment banker. The men hit it off immediately, as they shared a desire to perform public service to make a difference in the lives of suffering people. Walcott cabled the Foundation that the commission was a well-organized, effective organization. Meeting Hoover was a milestone for Walcott; the two would remain friends and political allies for years to come.

The Germans allowed Walcott safe passage into Belgium and invited him to tour Poland and Serbia. They claimed that they required outside food relief in order to adequately care for the Polish war refugees. This, of course, was part of a public relations scheme: The Germans portrayed themselves as caring occupiers to offset news accounts of their activities that cast them in a negative light.

The Germans allowed Walcott safe passage into Belgium and invited him to tour Poland and Serbia. They claimed that they required outside food relief in order to adequately care for the Polish war refugees. This, of course, was part of a public relations scheme: The Germans portrayed themselves as caring occupiers to offset news accounts of their activities that cast them in a negative light.

Walcott’s European tour began under a cloud of danger. Crossing the English Channel, the ship’s captain dodged mines. Walcott landed safely at Rotterdam. On its return voyage the ship hit a mine and sank.

Caspar Whitney, director of the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), accompanied Walcott. On the way to Brussels, Walcott got his first view of cities and villages that had been destroyed by German shells. Walcott likely did not enter German-held territory as an entirely neutral observer. The more he saw of the harsh treatment of civilians the angrier he got. Still, he managed to keep his opinions to himself. In Belgium, he sympathized with the civilians who were living under the rifle and gun of their occupiers, writing:

Gradually I seemed to sense the suffering that all of this [destruction and occupation]implied, the terrible mental strain that comes from living under a military despotism that is scientifically and methodically cruel, following the shock that comes from the spoliation of a nation. It had all been done so systematically and so thoroughly that the first thing that impresses one is the marvelous efficiency and tremendous power of the force that produces such results.

Poland had been occupied by Russia long before the Germans invaded. Walcott quoted one Pole as saying, “When the Russians were here they hung us; now that the Germans are here, we hang ourselves.” His German host took him to shelled and burnt Warsaw. As the Russians retreated from Warsaw, leaving it to the Germans, they set fire to the city and followed a “scorched earth” strategy, leaving no food to help the Poles get through the winter.

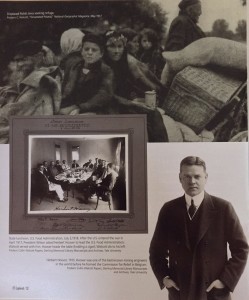

After Warsaw fell, in September and October 1915, about a million Polish refugees followed the retreating Russian army on the road to Pinsk. Near starvation and sick with disease, the refugees died in “indescribable suffering,” according to one eyewitness account. Walcott described the scene of this human catastrophe: “The remnants of clothes and the wicker baby baskets marked the places where the [refugees]stopped for the night. There were no graves. Bones were seen picked clean by the crows, which everywhere were in great numbers.” The Germans boasted that they gathered those bones and made them into fertilizer. Walcott stopped counting the wicker baskets, which were traditional “cribs” for Polish infants, because the number had grown so high. Walcott would describe this scene over and over again for the rest of his life.

Walcott and Hoover agreed that there was a need for relief in Poland, and they raised awareness for their cause by placing news stories into English newspapers. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., however, cautioned Walcott not to give interviews to the press without clearance, since the United States was a neutral country. The Rockefeller Foundation promised money for Poland after pledging funds for Belgium, but the logistics and politics among rival groups in Poland and between the combatant nations threatened to derail the food for Poland campaign. Upon his arrival in Europe, he had wondered how he could contribute to the Allies. Food for the hungry became his duty, and he told Rockefeller that he had never worked so hard for anything as he had to get food for Poland. In 1916, Walcott returned home. He published articles in the National Geographic about the plight of the Poles in 1917 and 1918 and a small tract in 1917 condemning the Prussian “system” of occupation.

Walcott’s work with Herbert Hoover to raise awareness of the plight of those living under German occupation made him famous as a humanitarian. After the U.S. declared war on Germany in April 1917, he agreed to work for Hoover in the newly created United States Food Administration. He was 48, and his life’s passion had shifted as a result of his first-hand observation of destruction, hungry and ill-clothed people, and the hundreds of empty wicker baskets along the road from Warsaw to Pinsk he saw in early 1916.

Mark H. Jones is the state archivist.