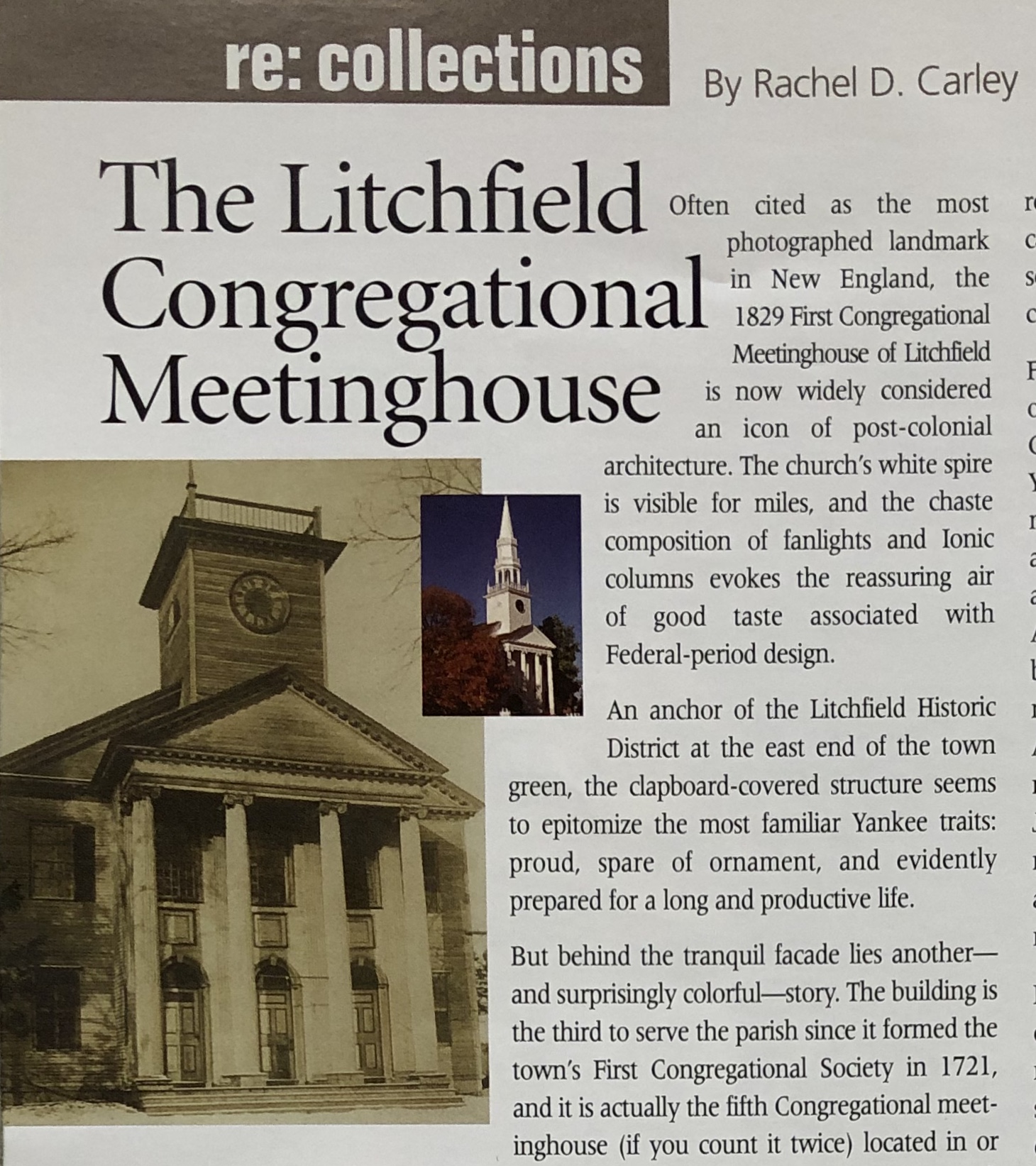

The Litchfield Congregational Meetinghouse, c. 1910, sans its steeple, when it was known as Colonial Hall. inset: the meetinghouse today. Litchfield Historical Society

by Rachel D. Carley

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2005/2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Often cited as the most photographed landmark in New England, the 1829 First Congregational Meetinghouse of Litchfield is now widely considered an icon of post-colonial architecture. The church’s white spire is visible for miles, and the chaste composition of fanlights and Ionic columns evokes the reassuring air of good taste associated with Federal-period design.

An anchor of the LItchfield Historic District at the east end of the town green, the clapboard-covered structure seems to epitomize the most familiar Yankee traits: proud, spare of ornament, and evidently prepared for a long and productive life.

But behind the tranquil facade lies another — and surprisingly colorful — story. The building is the third to serve the parish since it formed the town’s First Congregational Society in 1721, and it is actually the fifth Congregational meetinghouse (if you count it twice) located in or near the green, for it has been moved twice since it was erected.

The 1829 structure, fronted by an impressive Ionic portico, was dedicated on its first site shortly after the departure of one of the congregation’s most famous pastors, the Calvinist minister Lyman Beecher (1775 – 1863). The new building replaced the 1762 red-painted meetinghouse (the town’s second) where Beecher held forth on the perils of drinking and other sins even as the building around his congregation fell into increasing disrepair. In 1826 an anonymous visitor was so appalled by its condition that he wrote to the Litchfield County Post in criticism of Litchfield residents for lavishing improvements on their homes, courthouse, and banks while showing little concern for the appearance of God’s own house.

A fashionable Episcopal Church building also put the Congregationalist parish to shame, and plans for a replacement were soon initiated. By the 1820s Church and State were officially separated in Connecticut, and Congregational meetinghouse design was taking on a more “churchly” appearance. Secular activities such as town meetings had been removed from the formerly all-purpose meetinghouse (rarely called a church before 1800), and the architecture adopted some of the grander features of the current styles, such as the columned portico of the new Federal-style Litchfield example.

For all its grand styling, the 1829 church was considered outdated in just a few decades’ time. A more fashionable Gothic-style replacement was built in 1873. In a show of Yankee thrift, the 1829 building was saved, shorn of it steeple, moved a few hundred feet around the corner, and demoted to a variety of secular uses over the next 50 years, including stints as a movie theatre, roller-skating rink, and basketball court. After a 1920s Christmas card picturing a painting of the old building generated nostalgia for the 1829 church, interest mounted in returning the earlier structure back to the green. As the Gothic style fell out of favor and the Colonial Revival reached its zenith, parishioners hired architect Richard Dana, Jr., a specialist in Colonial Revival design, to oversee a renovation. The 1873 wooden Gothic church was torn down, and the refurbished 1829 church, its pulpit and spire restored, re-opened on its original site for services in 1930.

Listed in 1968 on the National Register of Historic Places as part of the LItchfield Historic District, the meetinghouse still does not face a certain future. The 175-year-old structure confronts serious preservation needs, including repairs to the roof and domed ceiling. In recognition of the building’s significance, the church was awarded a $200,000 grant late last year by the White House MIllennium Council and the National Trust for Historic Preservation with a grant for the J. Paul Getty Trust to help preserve the nation’s threatened cultural resources.

The Litchfield meetinghouse was one of 35 properties to receive such a grant in 2004, but the job of raising monies for repairs is not yet done, as the $200,000 requires an equal match. Last year townspeople funded Friends of the Meetinghouse, a secular committee, to continue raising funds as part of a total $1.6-million repair-and-restoration campaign that will also help the church to paint the building and to install a new furnace and fire-protection system.

For more information on the Friends of the Meetinghouse effort, contact the office of the First Congregational Church of LItchfield at (860) 567-8705.

Rachel Carley is an architectural historian and preservation consultant who lives in Litchfield.

Explore!

Read more stories about Historic Preservation on our TOPICS page.

More stories about Litchfield:

“Litchfield’s Fortunes Hitched to the Stagecoach,” Spring 2008

“The Influence of the Litchfield Law School,” Fall 2016

“Oliver Wolcott: The People’s Governor,” Fall 2018