by Cecilia Bucki

(c) Connecticut Explored WINTER 2013/14

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Connecticut’s historical self-image has long been associated with its sturdy Yankee farmers and craftsmen who built the new nation, sailed the seas for whales and fish, felled the forests, dug the earth for metals, and produced goods and sold them through a network of Yankee peddlers. In the colonial and early national periods, pockets of manufacturing existed in the market towns. Traditionally, artisans owned their own tools and plied their craft in workshops owned by master craftsmen who employed and worked alongside journeymen and apprentices. Artisans made everything related to their craft. Iron forgers, for example, dug ore from the Litchfield Hills, chopped trees and burnt wood to make charcoal, and then used this fuel and their skills to heat open furnaces and extract iron from the ore and purify it into wrought iron for use in metal-working shops. Artisans continued the practices of European guilds, with internal regulations about how products were made and how apprentices were trained. The goal for the pre-industrial artisan was not “profit” as such, but a good standard of living and a “competence” or savings for old age.

All this changed as the market revolution, aided by faster transportation afforded by canals and then railroads, got underway in the 1810s and 1820s. Some masters began subdividing the production process and hiring less-skilled workers to perform just one step in making a product. This undercut the artisan system, and craftsmen responded in the 1830s by organizing mechanics’ associations that made demands on employers about “prices” (piece-rates) and the length of the working day. General trades unions appeared in major cities along the Atlantic seaboard, demanding the ten-hour day and an end to imprisonment for debt. When the financial panic of 1837 caused wage cuts and then layoffs, these movements added unemployment to their list of grievances. In Connecticut, chapters of the New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics and Other Workingmen worked toward such changes, elected their members to the general assembly, and protested poll taxes.

Job actions followed, and employers responded by petitioning the courts, where decisions reinforced the so-called doctrine of criminal conspiracy against labor organizations. In 1834 the Thompsonville Carpet Company in Enfield sued striking Scottish carpet weavers for interrupting business. The expert carpet weavers, using hand looms in this non-mechanized business, had gone on strike over prices and new work rules and had communicated their strike to other carpet weavers in the region, asking them not to take jobs at the company. The jury—made up of local farmers—acquitted the weavers; labor economist John R. Commons declared in his 1910 History of American Industrial Society that this was an important early legal victory supporting the right of employees to form unions.

Textile companiesin Massachusetts and Rhode Island became the first to bring mechanized production to the textile industry in the 1810s and 1820s—and with it, large-scale factory work. Entrepreneurs followed suit in eastern Connecticut, where textile mills sprouted up along waterways. Women, specifically daughters of Yankee farmers, became the first mill workers. Once seen as providing opportunity for farm families to earn extra cash and for teenage girls to get off the farm, by the 1840s these mills had become unhealthy and harsh workplaces that caused female mill workers to join with the New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics and Other Workingmen to lobby for the ten-hour day.

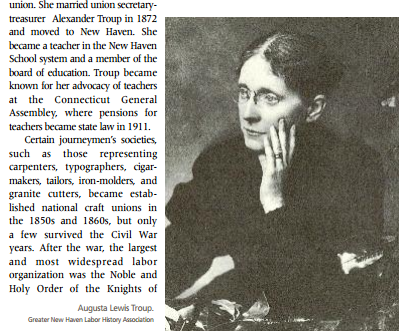

The composition of the largely homogenous population in Connecticut changed with the massive influx of Irish immigrants fleeing the Great Potato Famine of the 1840s. While Irish labor gangs had built the canals and then the railroads of early 19th-century Connecticut, their larger scale immigration took them to the mills and factories of the state and facilitated the mechanization of Connecticut industry. Irish families took the place of Yankee farmers’ daughters in textile mills by the 1850s. Women were less likely to break into skilled trades. One notable exception was Augusta Lewis (1848-1920), who successfully founded a women’s craft union in New York. As a single woman in the 1860s, “Gussie” trained as a compositor at a printer’s shop and founded the Women’s Typographical Union (WTU) No. 1 in 1868 in Manhattan. Since its founding in 1853, the National Typographical Union had refused to accept women as members. That changed during the 1869 strike when members of WTU No. 1 refused to act as strikebreakers; WTU was admitted into the International Typographical Union (ITU) that year. In 1870, she was elected corresponding secretary of the ITU, making her the first woman to hold office at the national level in any American union. She married union secretary treasurer Alexander Troup in 1872 and moved to New Haven. She became a teacher in the New Haven School system and a member of the board of education. Troup became known for her advocacy of teachers at the Connecticut General Assembly, where pensions for teachers became state law in 1911.

Certain journeymen’s societies, such as those representing carpenters, typographers, cigarmakers, tailors, iron-molders, and granite cutters, became established national craft unions in the 1850s and 1860s, but only a few survived the Civil War years. After the war, the largest and most widespread labor organization was the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor (KOL), whose members dedicated themselves to creating an alternative to the capitalist marketplace. The KOL, founded as a secret society in Philadelphia in 1869, sought to claim dignity and fair working conditions for its members through workplace organization, creation of producer and consumer cooperatives, and political action. The KOL did not believe in strikes, preferring the tactic of persuasion and the boycott.

By 1886, the KOL had 188 local assemblies and an estimated 12,000 members in Connecticut, including many female textile workers. Thirty-seven KOL members were elected to the state general assembly, where they resurrected the Bureau of Labor Statistics, enacted mechanics’ lien laws, and made illegal the common employer practice of withholding wage payment for a month or more. The KOL was unusual as a labor movement in that it saw itself as representing working people outside of work itself, in neighborhood organizations, in cooperatives and such. The KOL lost its influence after the 1886 Chicago Haymarket affair, in which it neither supported the eight-hour day strikes nor approved the anarchist leadership of the strike there. Its legacy includes its use of boycott as a tactic, the healing of the rift between Protestant and Catholic workers, its inter-racial unionism, and its slogan “An Injury To One Is an Injury to All,” which became the slogan for the entire American labor movement.

Meanwhile, the craft unions rebuilt themselves, survived the depression of 1873-1877, and combined to form the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1886. The AFL-affiliated craft unions took in members from many workplaces into the same local or lodge in an area, limiting membership to those who met the skill and training requirements of the union. The national AFL became the self-proclaimed representative for all American workers. But its members now faced highly mechanized workplaces.

Meanwhile, the craft unions rebuilt themselves, survived the depression of 1873-1877, and combined to form the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1886. The AFL-affiliated craft unions took in members from many workplaces into the same local or lodge in an area, limiting membership to those who met the skill and training requirements of the union. The national AFL became the self-proclaimed representative for all American workers. But its members now faced highly mechanized workplaces.

Labor defeats across the nation during the 1890s depression weakened many unions. The AFL style of “business unionism” became the more prudent course, compared to either the more visionary KOL approach or the industrial-style unionism of the American Railway Union during the 1894 Pullman Strike. The AFL’s slogan “A Fair Day’s Wage For a Fair Day’s Work” summed up a more limited vision for craft unions.

By 1900, the American workforce changed as manufacturing companies began hiring thousands of new, unskilled eastern and southern European immigrants. Socialists such as Eugene V. Debs were convinced that only industrial unionism (which welcomed every worker in the workplace, not just the skilled craftsmen) was the key. In 1905, these activists established the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which aimed to create one big union of all workers to organize for their own protection and build a future where workers ruled the economy and their own workplaces. The IWW sent ethnic organizers to speak to workers in their own languages. The strategy worked. Immigrant textile and garment workers flocked to the IWW. Hartford labor activist Stephen Thornton (see shoeleatherhistoryproject.com) has documented at least 15 strikes throughout Connecticut in the years 1909-1919 in which the IWW was involved; 9 in which the strikers were victorious.

Meanwhile, skilled workers in AFL unions, including carpenters and those working in other building trades, machinists, brass casters, metal polishers, bakers, and cigar-makers, also had successes. Most Connecticut employers, however, remained resolutely anti-union. In 1902, Danbury hatters became a national cause when employer Dietrich Loewe refused to recognize the hatters’ union and most of his employees went on strike. When Loewe reopened his factory with strikebreakers, the striking workers organized a boycott against Loewe’s hats wherever they were sold. Loewe sued the union and its members, and, after six years in federal courts, the U.S. Supreme Court in 1908 ruled against the strikers. Citing the new Sherman Anti-Trust Act, the court found the strikers had unlawfully restrained trade and awarded triple damages to the company. Faced with the possibility of losing their homes, the members of the hatters’ union organized a “Hatters’ Day,” asking all members nationwide to donate an hour’s wage to help pay the fines. Many other Connecticut labor unions participated in this fund drive.

It was in the Progressive Era (1897- 1914) that the national AFL began supporting Democratic Party candidates in return for favorable labor legislation to overcome these negative court decisions. This era saw many reforms implemented, including the Connecticut Workmen’s Compensation Act in 1913 (see page 46). Unfortunately, the law was weak on occupational diseases, so that cases of brass-casters’ “spelter shakes” (zinc poisoning) and “mad-hatter” disease (mercury poisoning) were rarely compensated. Historian Claudia Clark, author of Radium Girls (University of North Carolina Press, 1997), discovered that female watch-dial painters at the Waterbury Clock Company did not receive health care or compensation for radium poisoning from the luminous paint used on watch faces in the 1920s.

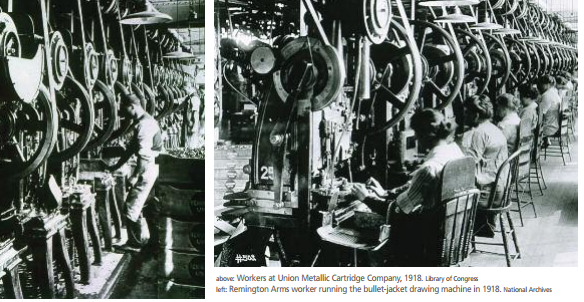

The state’s unions, like the economy, remained weak in many sectors. Connecticut industry flourished with the beginning of World War I in Europe in 1914. Munitions, firearms, cannon, and even submarines were built in Connecticut. The war years changed American society, as the decline in European immigration increased the number of industrial jobs available to Southern African Americans who migrated to Northern cities, and created opportunities for women to fill previously unavailable metal-working jobs in expanded manufacturing facilities.

In Connecticut, nowhere was the war’s impact greater than in Bridgeport. A crisis over management’s attempt to undercut skilled craft work, craft workers’ attempt to defend their jobs, the eagerness of immigrant men and women workers to gain well-paid industrial work, and the national war effort led to a series of spectacular strikes in Bridgeport during World War I that attracted national attention and the concern of the federal government. Bridgeport was one of the cities that expanded greatly through war production. By the end of 1915, Bridgeport factories were supplying two-thirds of the small arms and ammunition to the European war theater, earning the city the nickname “The Essen of America” (referring to the German city that was the center of the German munitions industry). The giant factory built by Remington Arms Company in Bridgeport’s East Side, the largest factory in Connecticut in 1915, symbolized the extensive building campaigns undertaken by machine shops and munitions producers. By summer 1915, full employment led the city’s craft unions of carpenters and machinists to strike to demand the eight-hour day (a 48-hour week, since Saturday was a full workday) and unionization of workplaces throughout the city. That strike spurred the rest of the city’s workforce, including workers from Warner Brothers Corset Company, Remington Arms, Bullard Machine Tool Company, and even restaurants and laundries, to walk off the job. Employers agreed to the eight-hour day, but most declined to accept unions, except for the munitions plants, where the International Association of Machinists (IAM-AFL) achieved a stronghold.

The newly elected IAM business agent Samuel Lavit, rumored to have been an IWW activist, believed in industrial unionism and set out to unionize the city’s entire metal-working industry. He welcomed the new immigrant workers hired to semi-skilled machine operator positions. He recruited women who were being hired into better-paying jobs in Remington Arms-Union Metallic Cartridge Company. The Bridgeport IAM grew tremendously, setting up four new lodges (the IAM name for locals), including a Polish lodge and a women’s lodge.

When the U.S. declared war in April 1917, all government contracts came under the jurisdiction of the new National War Labor Board (NWLB). The NWLB, created in response to the AFL’s no-strike pledge, was set up to mediate labor disputes and break through the antiunionism of major American industry. Lavit and the Bridgeport IAM petitioned the NWLB for wage increases and filed grievances against companies that paid women less than men for the same job or did not pay overtime after eight hours as federal contracts stipulated.

Ignoring federal rules, skilled machinists went out on strike in March 1918 over Good Friday holiday pay. Strikes by various munitions workers continued throughout the summer until President Woodrow Wilson ordered those workers back to work after Labor Day 1918. The wave of strikes by Bridgeport machinists had given the federal government an unprecedented model for settling labor disputes, achieving the eight-hour day, allowing immigrant men to join unions, and affording women equal pay for the same work [see Cecelia Bucki, Bridgeport’s Socialist New Deal, 1915-1936 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001)]. After the war, employers tried to roll back workers’ gains, and in 1919 a nationwide strike wave saw four million industrial workers go on strike. The unions lost most of the strikes, and budding unions were destroyed. Only pockets of craft workers, especially in the building trades, were able to hang on to their organizations.

The vision of industrial unionism, however, would have to wait to be achieved during the next economic crisis, the Great Depression. After a decade of anti-labor and anti-immigrant sentiment in the 1920s, the Great Depression gave rise to a renewed labor movement. Amid the organizing of Unemployed Councils in working-class neighborhoods of major cities, workers who had been unionized during World War I began to re-organize. It was not until the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933, though, that unions began to regain a foothold.

Many strikes engulfed Connecticut workplaces in late 1933 and 1934. One spectacular national strike that had an impact on the state was the textile strike of 1934. It originated in Southern states, where many textile companies had fled to avoid the union movement. In eastern Connecticut, roving squadrons of strikers moved from one mill to the next to encourage support for the strike. They came up against the state militia, who had been ordered into service to keep the peace.

Many strikes engulfed Connecticut workplaces in late 1933 and 1934. One spectacular national strike that had an impact on the state was the textile strike of 1934. It originated in Southern states, where many textile companies had fled to avoid the union movement. In eastern Connecticut, roving squadrons of strikers moved from one mill to the next to encourage support for the strike. They came up against the state militia, who had been ordered into service to keep the peace.

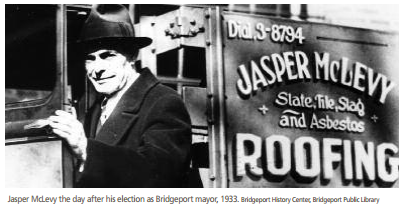

The unions lost many of the strikes in 1933 and 1934, but the Democratic Governor Wilbur Cross did support some labor legislation and allowed his Labor Commissioner Joseph Tone to pursue an anti-sweatshop campaign. Labor saw increased political power as trade unionist and Socialist Jasper McLevy won City Hall in Bridgeportin 1933 and Bridgeport voters then elected Socialists to state offices. Similarly, Democrats backed by labor won mayoralties in many other Connecticut cities. The New Deal included federal government attempts to overcome the wealth gap between rich and poor by strengthening the weaker party— workers—in collective bargaining to raise wages.

The 1935 Wagner Act set up the National Labor Relations Board to oversee collective bargaining to deal with labor disputes. The Wagner Act resulted in an organizing upsurge in basic industry, a split in the AFL, and the creation of an industrial union federation, the Committee (later Congress) of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

CIO unions spearheaded union drives in such industries as steel, auto, and electrical; by 1940 many Connecticut factories had been unionized. The largest CIO unions in Connecticut were the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers (UE) and Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (MMSW). AFL unions such as the IAM adapted to the changing times and began to organize along industrial lines. All did not go smoothly, as the machinists’ strike at Middletown’s Remington-Rand Typewriter factory demonstrated. In July 1936, when the IAM failed to reach an agreement with owner James Rand, the workforce struck there and at Remington-Rand’s other plants in upstate New York. Rand launched an anti-union campaign that became known as the “Mohawk Valley Formula,” in which he labeled unionists as “outside agitators,” threatened to move the plant out of town, organized “citizens’ committees” of local businessmen to counter the local appeal of the union, and refused to negotiate. The Middletown plant remained closed until the early 1940s. (See Marta Moret, A Brief History of the Connecticut Labor Movement (Labor Education Center-UCONN, 1982).)

World War II brought unionization to most major industries, as the War Labor Board expanded the reach of the federal government into almost every facet of the economy through government war contracts. Federal oversight guaranteed business profits and a good standard of living and working conditions for the state’s working class. In exchange for agreeing to wage freezes, many unionized workers received new fringe benefits such as paid sick leave and paid vacation days.

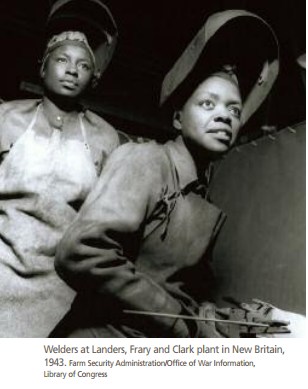

Connecticut society changed dramatically during the war years as Southern African Americans and Puerto Ricans migrated to Connecticut defense jobs and “Rosie the Riveter” appeared on many shop floors. What had been the experience for some women in Bridgeport during World War I now became widespread during WWII, when women were recruited to fill expanding factories and jobs vacated by men drafted into the military. At war’s end, the improved quality of life and fringe benefits newly associated with union membership helped create a new middle class.

CIO unions struck nationwide in 1946 to retain wartime gains and to secure a wage increase to make up for the loss of wartime pay and the rising cost of living. Connecticut’s biggest strike was at the General Electric plant in Bridgeport, with 25,000 workers walking off the job. In January 1946, an estimated 10,000 workers rallied in Stamford for a one-day strike, proclaiming, “We Will Not Go Back to the Old Days,” according to historian George Lipsitz in Rainbow at Midnight (University of Illinois Press, 1994). This strike wave produced small wage increases, and, unlike in the aftermath of the 1919 strike wave, unions remained intact in the nation’s workplaces.

The CIO lost its political momentum in the post-war years as the new Cold War and fear of Communism created an internal conflict in the labor movement. The national CIO expelled 10 unions in 1949 for being “Communist-dominated.” The UE and MMSW were two of these. Other CIO and AFL unions rushed to supplant the expelled unionsin many Connecticut workplaces, leading the labor movement in Connecticut to focus inward rather than continue to press for progressive societal changes. The CIO, purged of its radicals, merged with the AFL in 1955 to form the AFL-CIO. The rest of the 1950s saw stasis, as continued economic prosperity led to stable labor relations, though strikes were not unheard of.

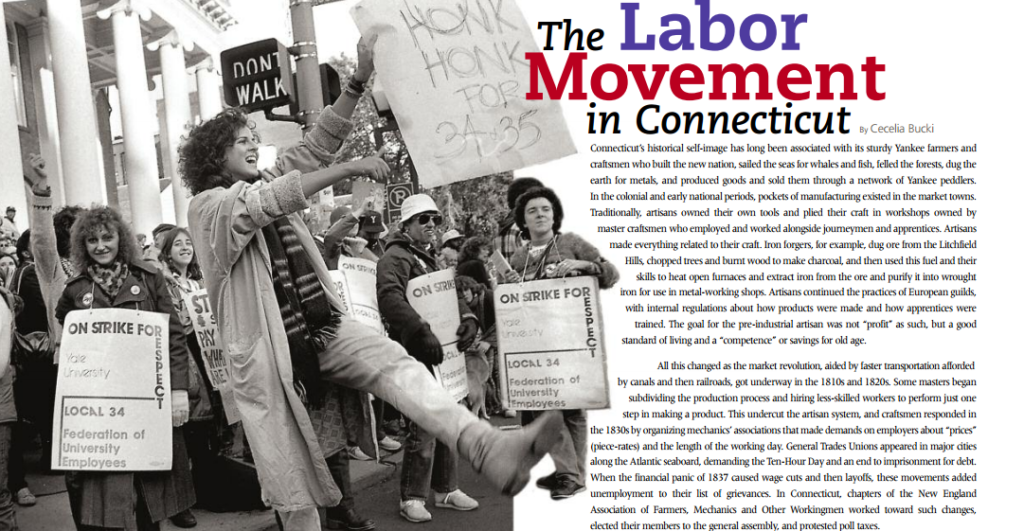

In the 1960s, service-sector and white collar jobs increased in number and expanded women’s employment, though these economic sectors were non-union. But industries began moving to the south and west, and then off-shore, to nonunion regions, leading to widespread “deindustrialization” in the state. Union membership declined with the loss of these jobs. Public employment expanded, and municipal workers gained the right to organize. State workers earned that right in 1973, which spurred other clerical workers in the private sector to unionize. Teachers successfully organized around the state, though in 1975, when New Haven teachers struck, 100 were arrested for violating a court injunction. Female trade unionists, once a rare sight, became much more visible with the establishment in 1975 of a Coalition of Labor Union Women chapter in Hartford. Health-care workers began organizing in the 1960s, often in tandem with the civil-rights movement; District 1199-Connecticut marched for both civil rights and labor rights for its members in nursing homes and some hospitals. Most recently, union drives in food service and custodial services in the 1990s and 2000s have led to unionization on university campuses and in some private businesses. These economic sectors include large numbers of new immigrants. Less successful in organizing have been the estimated 40,000 migrant farm workers who enter the state every summer to grow and harvest the state’s vegetable and fruit crops, along with shade tobacco.

Working people and their unions are faced today with an increasing wealth gap that threatens the American Dream of a home and a good standard of living. How can working people protect themselves and their families in this rapidly changing economy? Wage levels have been stagnantsince the 1980s. Anger overtaxes has placed public-sector workers at the center of public-policy debate. These workers find themselves under attack for retaining their good wages and benefits, even as private-sector workers lose their pensions and even their jobs. Teachers find themselves blamed for their students’ lackluster achievements, as education funding is slashed. The federal labor law that protected collective bargaining since the 1930s no longer works, and the union movement now looks back to the community-organizing models of the Knights of Labor, the IWW, and the CIO. Will union leaders return to seeing themselves as representing all working people and not just their members? Will the political system allow for such innovation? History cannot predict the future; it can only remind us of where we have been.

Cecelia Bucki, professor of History at Fairfield University, is a labor historian.

Explore!

Read more stories about Labor History in Connecticut on our Topics page.