By Laura Smith

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

What is a railroad company to do when it can’t get people to stop complaining about late trains, the lack of seats, and long waits in the dining cars—especially under the strain of wartime? If you were the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad during the years of World War II, you would put out one of the most successful advertising campaigns in American history.

The New Haven Railroad (as it was commonly known), which provided passenger and freight service to southern New England, including New York City and Boston, suffered during the Great Depression. But it had a resurgence in World War II, mostly due to its proximity to these two crucial ports. As reported in the company’s annual report for the year ending December 31, 1942, many industries in the Northeast converted to wartime production, and these products needed to be transported by train. Along the east coast the threat from German submarines diverted the transport of petroleum and coal from shipping to rail. Passenger service was up, too, due to civilian rationing of tires and gasoline and increased troop transport. The railroad carried 54.3 million passengers in 1942, an increase of more than 37 percent from the year before, according to the company’s 1942 annual report. The Dining Car Department reported serving more than 1.8 million meals, an increase of 66 percent.

But just as business boomed, the New Haven Railroad lost 4,700 employees to military service in 1942. Increased shipping of munitions and wartime supplies resulted in fewer trains and seats available for the general riding public. Riders constantly complained about poor service, according to James B. Twitchell in 20 Ads that Shook the World(Crown, 2000) and Charles Pinzon and Bruce Swain in “The Kid in Upper 4” (Journalism History, Fall 2002), and inferred from articles in the railroad’s Rider’s Digest distributed to passengers beginning in 1942.

Under tremendous strain and with limited options, in the fall of 1942 the railroad turned to its advertising agency, the Wendall P. Colton Company of Boston to bolster its efforts to change passenger’s behavior. The agency’s first approach was to illustrate the important role the New Haven Railroad played in the country’s efforts to win the war and defeat fascism. Two ads, “Right of Way for Fighting Might,” which ran in newspapers in New York City and New England in October 1942, and “Thunder Along the Line,” which ran in November 1942, were marginally effective in reducing riders’ complaints, according to Pinzon and Swain.

As Pinzon and Swain relate, in late 1942 the Colton Company turned to Nelson Metcalf Jr., a 29-year-old Harvard graduate who was fairly new to the advertising profession. Metcalf decided that the best approach was to play on the emotions of the riding public. With the country barely a year into a war that touched virtually every citizen, he surmised that most riders of the railroad had a father, husband, brother, or son in the military. His approach focused on the thoughts of one soldier awake in the dark on a troop train headed for the ship that would bring him face-to-face with the war. He was “The Kid in Upper 4.”

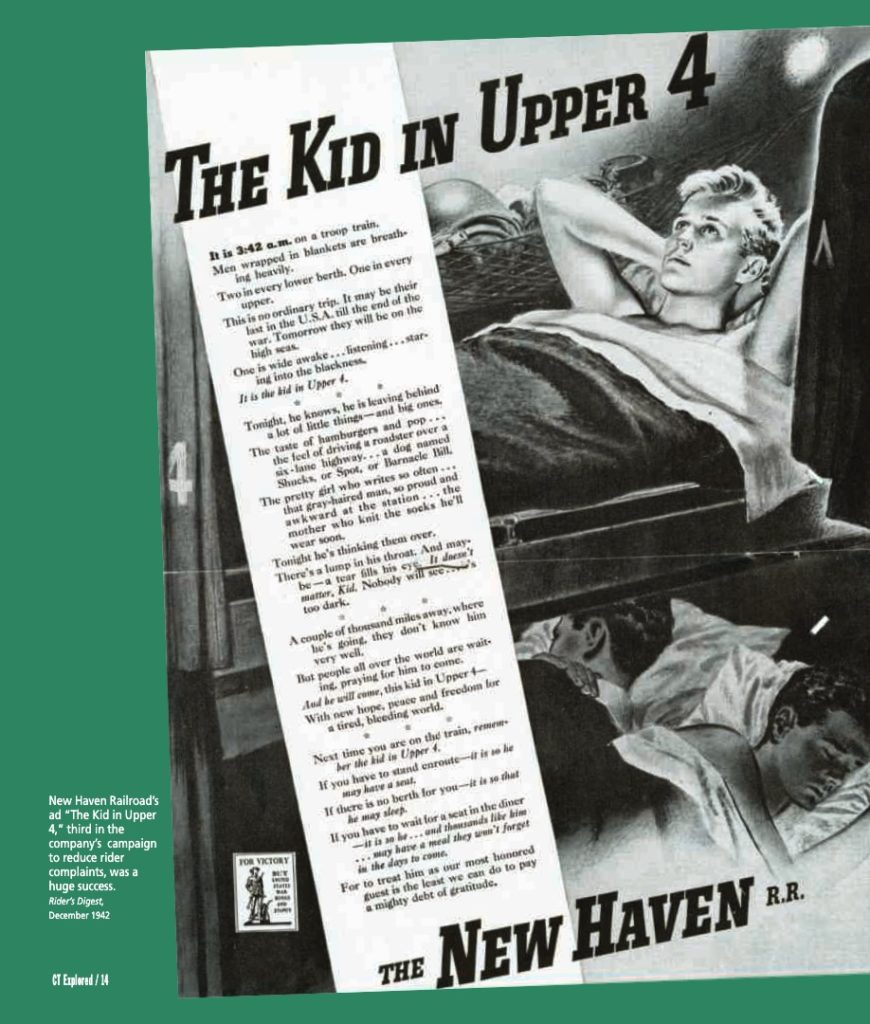

The ad showed a fresh-faced young man lying awake in upper berth number 4 in a sleeping car, with a long, emotive section of text. The “Kid” was thinking about what he had left behind, such as the taste of hamburgers and soda, his mom and dad, and the pretty girl “who writes so often.” An unseen narrator assures the reader that what lay ahead was no less than the salvation of humanity, bringing “new hope, peace and freedom for a tired, bleeding world.” This is what the “Kid” would deliver, with the help of the New Haven Railroad, of course.

With the last section of the text reminiscent of a church service’s call and response—“If there is no berth for you—it is so that he may sleep”—the message was enough to raise a lump in every rider’s throat. The messaging also intimated that denying a seat or berth to a brave young soldier, out of what was surely one’s own selfishness, was downright un-American.

The ad ran first in the New York Herald Tribune on November 22, 1942. As noted by Pinzon and Swain, the ad immediately struck a chord across New England. The January 1943 issue of the New Haven Railroad’s employee magazine, Along the Line, reported that passengers were observed visibly weeping upon reading the ad, overtaken with the maudlin words of this one soldier’s sacrifice.

The ad soon had an impact beyond New England. As reported in the January 1943 issue of Along the Line, the railroad and the ad agency immediately fielded calls and received letters with positive responses from the public, other businesses in the industry, and government offices. As noted by Twitchell, the ad was soon running in newspapers around the country, and in Life, Newsweek, and Time magazines. In the months that followed it was used to raise money for the Red Cross and to sell war bonds and by the U.S. Army to build morale among servicemen.

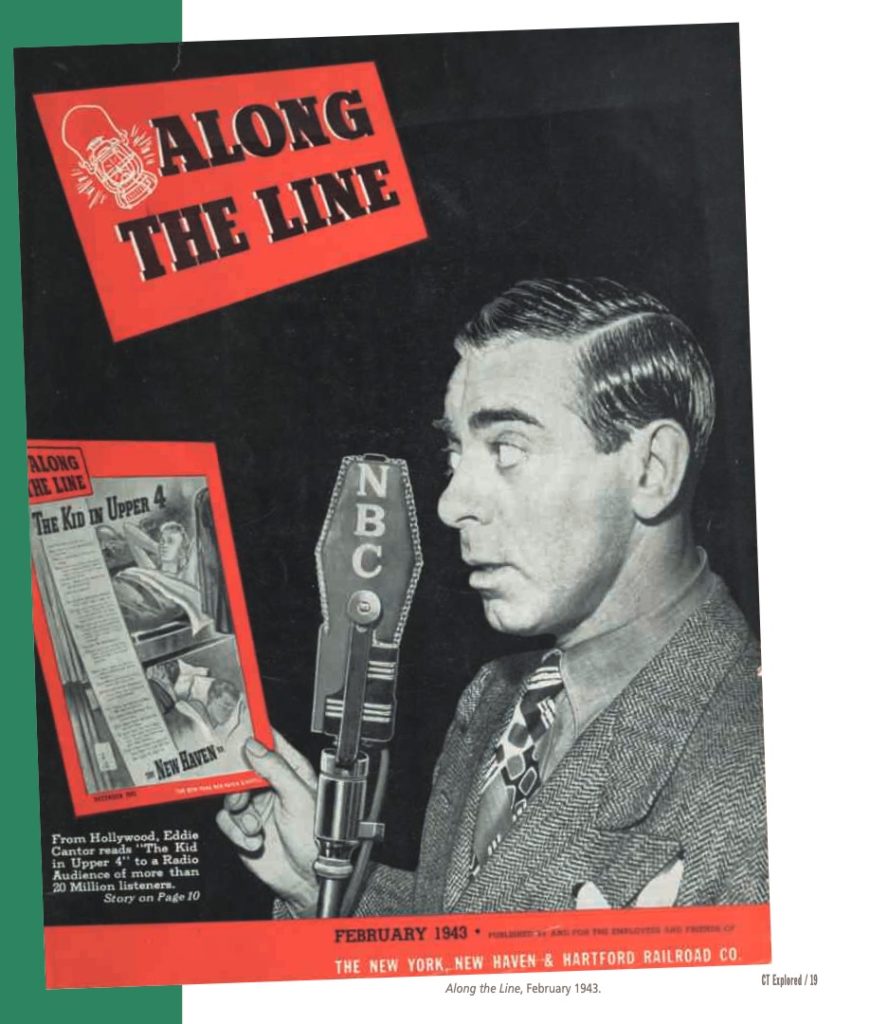

Along the Line later reported that thousands of reprints were requested by other companies, military units, and the general public. Pinzon and Swain note that “By the end of January 1943 even competing railroads had hung full-color posters of the advertisement in their terminals. Within four months of its publication a radio station had dramatized the ad, [famous comedian and actor]Eddie Cantor had read the copy over the air on his hit radio show, a popular song had been written, and [movie studio]MGM was in production on a film short.”

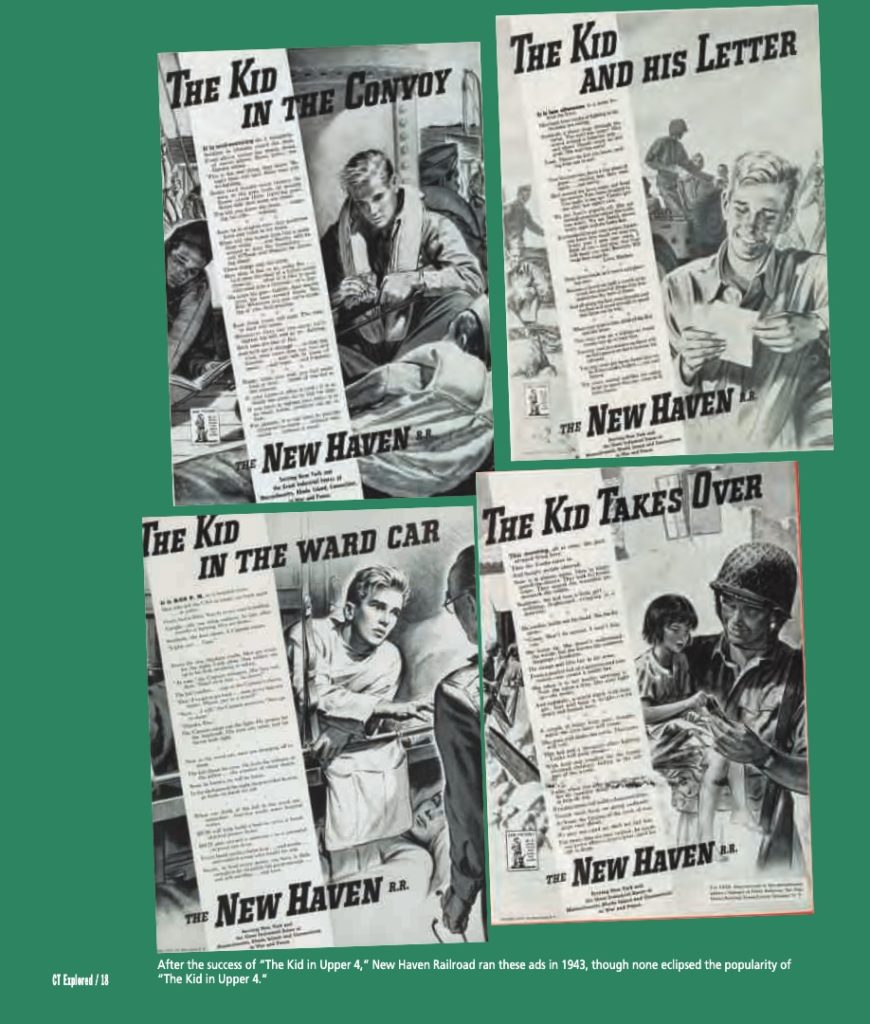

In the January 1943 issue of Along the Line, the editor wrote of the railroad’s delight with the ad’s success and that it soon ordered the agency and Metcalf to create more “Kid” ads. “The Kid in the Convoy,” “The Kid in the Ward Car,” and others soon followed. Though similar in tone, none had the impact of the original “Kid” ad, Pinzon and Swain noted.

In February 1943 the Jury of Annual Advertising Awards gave the company its Advertising & Selling medal “for conspicuous achievement in advertising” at a dinner at the Hotel Waldorf-Astoria in New York City, Along the Linereported. Twitchell lists “The Kid in Upper 4” among the most successful advertising campaigns in American history. He noted that the ad’s success was based on the fact that unlike the typical advertisement, it was not selling anything. Its brilliance, Twitchell asserts, was that it was effective in “drawing attention away from the client’s lousy product.”

Laura Smith is an archivist at Archives & Special Collections of the University of Connecticut Library and oversees the business, railroad, and labor history collections. She last wrote “Workers: Play Ball!,” Winter 2013/2014.

Explore!

Receive each beautiful and informative issue! Subscribe Today!

Read more stories about Connecticut in World War II in our Fall 2020 issue, and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page.

Read Laura Smith’s “Workers: Play Ball!,” Winter 2013-2014