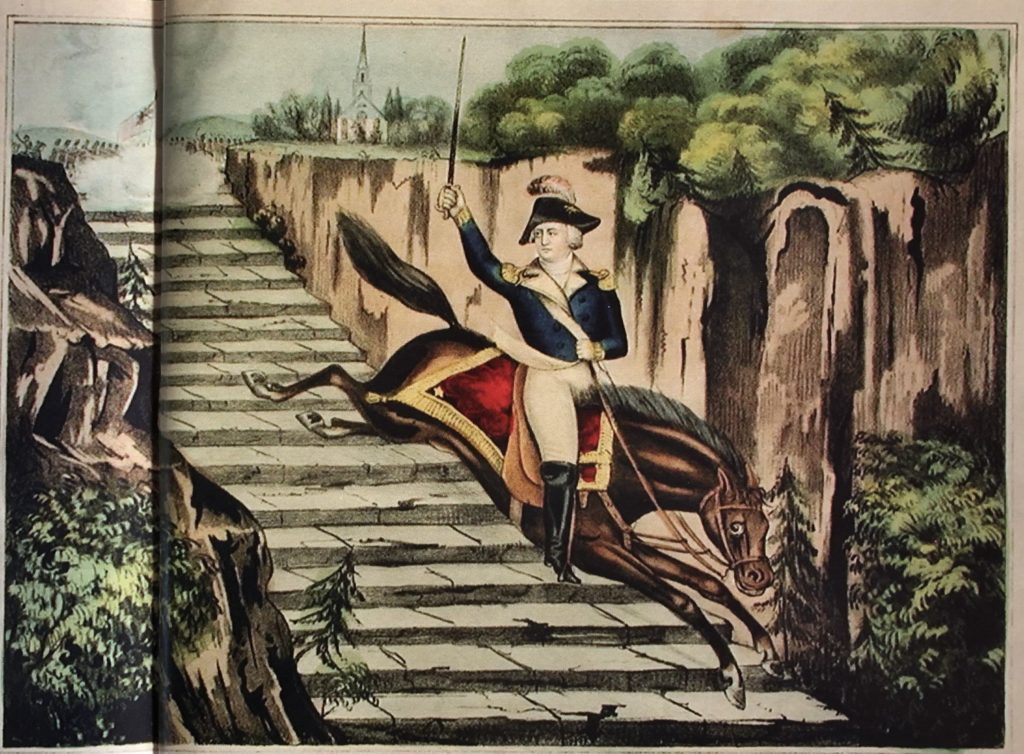

Genl. Israel Putnam. The Iron Son of “76” effecting his escape from the British Dragoons, 1845. Hand-colored lithography by E.B. & E.C. Kellogg. The Connecticut Historical Society

By Nancy Finlay

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

On January 6, 1834, an advertisement in the Connecticut Courant informed the public that D.W. Kellogg & Co. had “opened a Wholesale and Retail Print Store, in Main-Street, a few rods south of the City Hotel, where they keep constantly on hand a large assortment of superior FANCY PRINTS. Portraits, Landscapes, Views of Public Buildings, &c &c. taken at short notice. Booksellers, Book Agents, and other dealers in Prints are invited to call and examine for themselves. All orders from abroad promptly attended to.”

Lithography, literally drawing on stone, was developed in 1796 and in the 1830s became an exciting new technology that allowed huge quantities of prints to be produced quickly and inexpensively from a single design drawn on a polished piece of Bavarian limestone. Brothers Daniel Wright Kellogg (1807 – 1874), Edmund Burke Kellogg (1809 – 1872), and Elijah Chapman Kellogg (1811-1881) had begun printing and publishing lithographs in Hartford by 1832. Changing partnerships and firm names several times during the next 40 years, they emerged as one of the most important and productive lithographic businesses in the United States and the most successful competitors of Nathaniel Currier. Currier, who established his lithographic business in New York in 1835, joined with James Merritt Ives to form Currier and Ives in 1857. Hartford in the 1830s was a serious rival of New York as a center of printing and publishing, with more printing houses than any other town of its size.

Although the Kelloggs are best known for their “fancy prints” (decorative pictures created to satisfy the taste of an expanding middle class), they also produced printed matter for businesses throughout the state of Connecticut – and the country. An 1874 advertisement in The Manufacturer and Builder solicited orders for “check books, note books, draft books, order books, bill headings, letter headings, note headings…etc., etc.” The Kelloggs performed such “job” printing from the beginning, but this work became increasingly important as time went on.

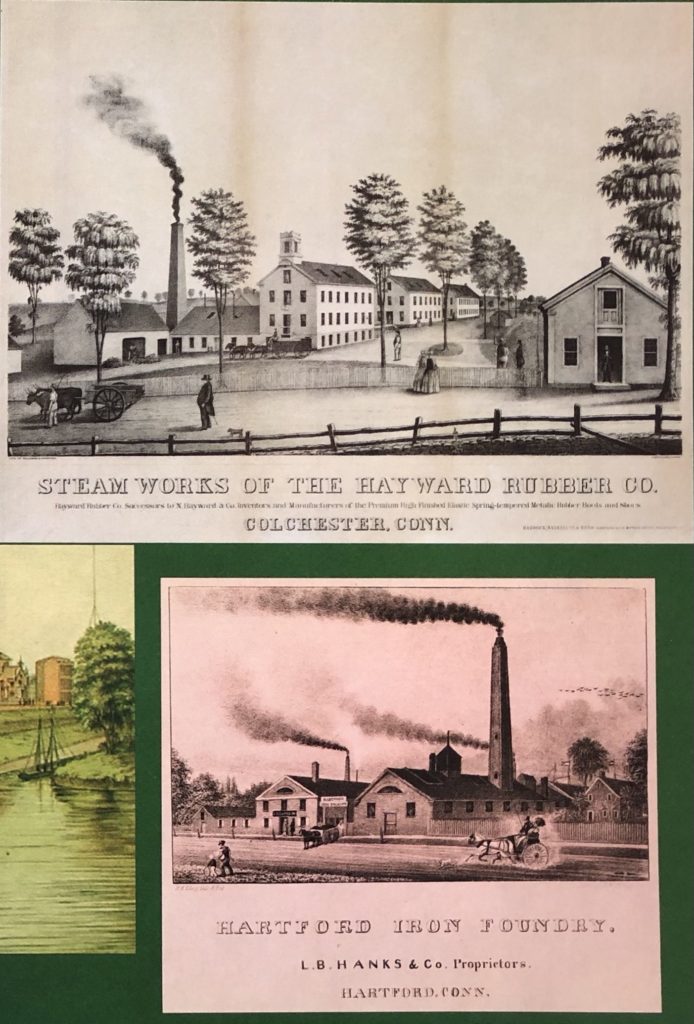

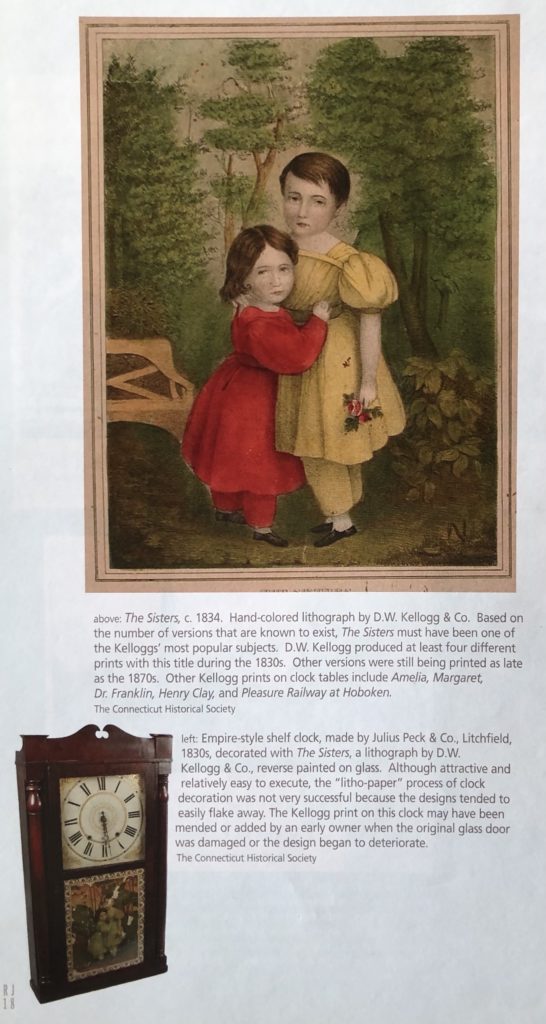

The Kelloggs produced posters or advertisements in which images combined with text were printed on large sheets of paper for posting on walls. They also issued a number of attractive views of factories, which, although many were framed to hang on the walls of the factories and in the offices of their employees and agents, were clearly used for advertising purposes as well. A print of the Hayward Rubber Works in Colchester, Connecticut, for instance, has an added line indicating that Haddock, Haseltine & Reed, at 164 and 166 Market Street, Philadelphia, were the rubber company’s agents in that city. During the 1830s, the Connecticut clock-making industry experimented with a process for using Kellogg prints in the decoration of glass doors of shelf-clocks. [For more about Connecticut clockmaking, see “Everyman’s Time: The Rise and Fall of Connecticut Clockmaking,” page 20.] A lithograph was attached to the back of a piece of glass with varnish or sizing. After this dried, the paper was moistened and rubbed off, leaving an ink image on the glass. The back of the glass was then reverse painted in bright colors to produce an attractive design. The Fenn collection at the American Clock & Watch Museum in Bristol includes D.W. Kellogg lithographs that were intended for this purpose. Examples of this form of decoration are most commonly found on clocks manufactured by Riley Whiting in Winchester, Connecticut, but The Connecticut Historical Society recently purchased a clock made by Julius Peck & Co. in Litchfield that is decorated with a Kellogg design, and other manufactures also made use of the process.

Kellogg designs found another application after Samuel Peck of New Haven invented die-stamped cases for housing daguerreotypes and other early photographs – the first plastic products to be patented and mass-produced in America. To decorate the cases, which were popular during the 1850s and 1860s, designs based on Kellogg prints were copied in miniature and engraved on metal dies; hot molten plastic was then pressed between the dies to form the two sides of the thermoplastic case.

By the late 1860s, when the last of the Kellogg brothers left the firm, “Printed Matter … [for]manufacturers, in the best style of the Lithographic art” had become the business’s key component. The firm continued to be known as Kellogg & Bulkeley, even though no members of the Kellogg family remained with the firm. In 1947, Kellogg & Bulkeley merged with Case, Lockwood & Brainard, another old Hartford business, to form Connecticut Printers, continuing the tradition of fine printing that Hartford had been known for since the early years of the 19th century.

Above: Israel Putnam’s ride is such a classic Connecticut subject that it seems likely that this Kellogg print is the direct source for the image on the daguerreotype case, even though Currier & Ives produced similar prints. Other Kellogg images on daguerreotype cases include Byron in the Highlands, First at the Rendezvous, Hawking and Household Pets. The Connecticut Historical Society

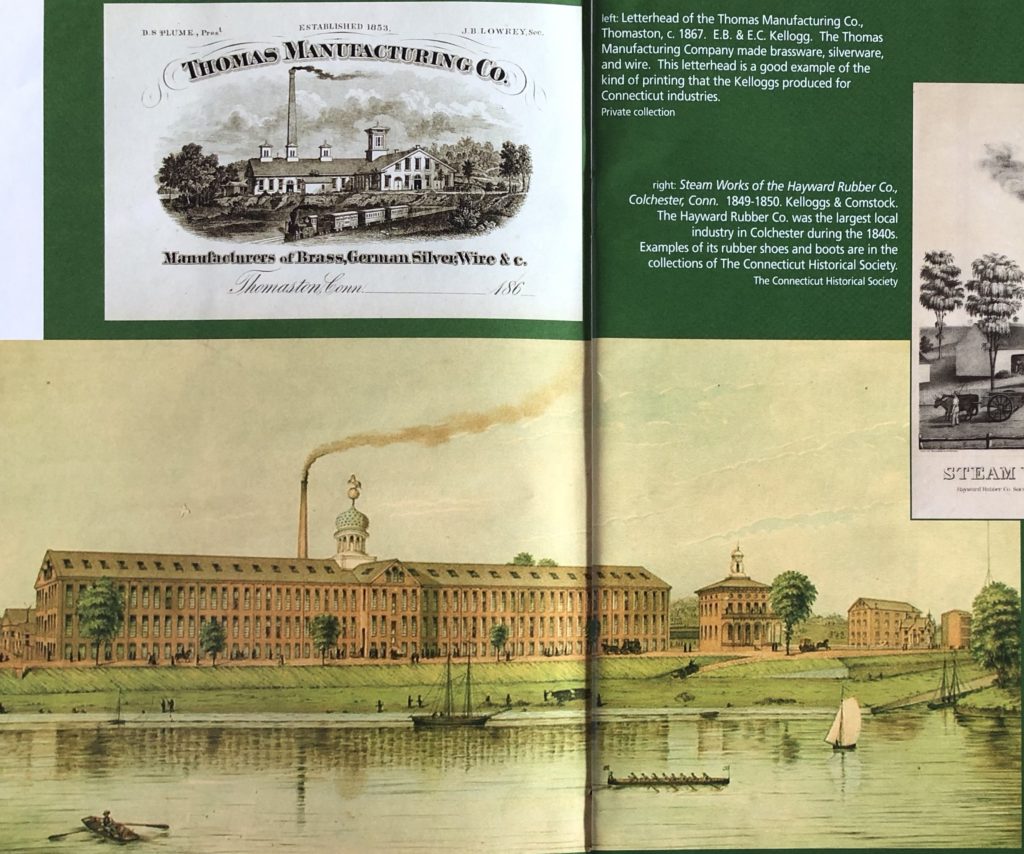

top: Letterhead of the Thomas Manufacturing Co., Thomaston, c. 1867. E.B. & E.C. Kellogg, private collection. Bottom: Armory of Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Manufacturing Company, 1840s. Color Lithography by E.B. & E.C. Kellogg. The Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

Above, top: The Thomas Manufacturing Company made brassware, silverware, and wire. This letterhead is a good example of the kind of printing that the Kelloggs produced for Connecticut industries. Above, bottom: Most Kellogg lithographs were printed in black and white and hand-colored. This view of the Colt Fire-Arms factory is an early experiment in color printing. The Kelloggs knew the Colts well and did other job printing for the factory.

top: Steam Works of the Hayward Rubber Co., Colchester, Conn. 1849-1850. Kelloggs & Comstock. bottom: tford Iron Foundry, c. 1834. Lithography by D.W. Kellogg & Co. after a drawing by Edward Williams Clay. The Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

Above, top: The Hayward Rubber Co. was the largest local industry in Colchester during the 1840s. Examples of its rubber shoes and boots are in the collections of The Connecticut Historical Society. Above, bottom: The Hartford Iron Foundry on Commerce Street established in 1821 and later reorganized as Woodruff & Beach, was the largest producer of heavy machinery in New England. The inscription on this print indicates that E.W. Clay transferred his drawing to the lithographic stone; it was then printed by D.W. Kellogg & Co.

top: The Sisters, c. 1834. Hand-colored lithography by D.W. Kellogg & Co. Bottom: Empire-style shelf clock, made by Julius Peck & Co., Litchfield 1830s, decorated with The Sisters, a lithograph by D.W. Kellogg & Co., reverse painted on glass. The Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

Above, top: Based on the number of versions that are known to exist, The Sisters must have been one of the Kelloggs’ most popular subjects. D.W. Kellogg produced at least four different prints with this title during the 1830s. Other versions were still being printed as late as the 1870s. Other Kellogg prints on clock tables include Amelia, Margaret, Dr. Franklin, Henry Clay, and Pleasure Railway at Hoboken. Above, bottom: Although attractive and relatively easy to execute, the “litho-paper” process of clock decoration was not very successful because the designs tended to easily flake away. The Kellogg print on this clock may have been mended or added by an early owner when the original glass door was damaged or the design began to deteriorate.

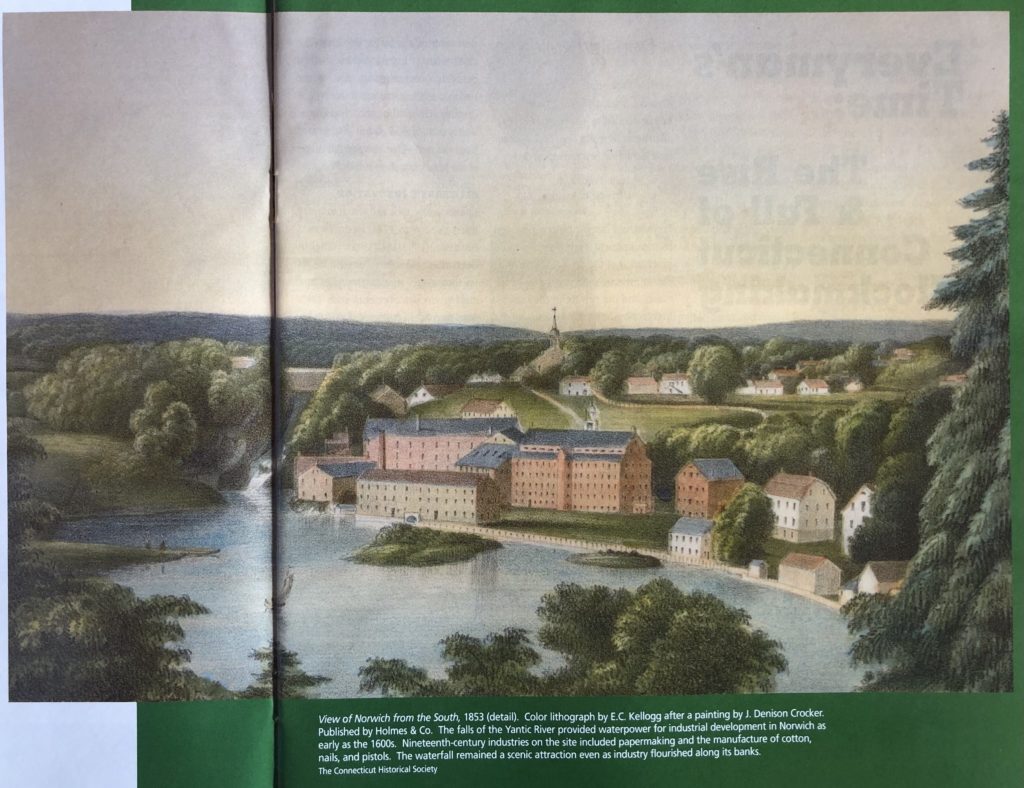

View of Norwich from the South, 1853 (detail). Color lithograph by E.C. Kellogg after a painting by J. Denison Crocker. Published by Homes & Co.

Above: The falls of the Yantic River provided waterpower for industrial development in Norwich as early as the 1600s. Nineteenth-century industries on the site included papermaking and the manufacture of cotton, nails, and pistols. The waterfall remained a scenic attraction even as industry flourished along its banks. For more images of Norwich by Crocker, see, “John Denison Crocker: Norwich’s Renaissance Man,” Winter 2006/2007]

Nancy Finlay is curator of graphics at The Connecticut Historical Society and a frequent “behind the scenes” collaborator on images for HRJ stories. She last wrote about daguerreotypist Augustus Washington in the Nov/Dec/Jan 2004/2005 issue.

Explore!

Read more stories from the Fall 2007 issue

“The Two-Million-Dollar Map,” Spring 2012

For more stories about Connecticut’s art history, visit our TOPICS page.

For more stories about products made and invented in Connecticut, list our TOPICS page.

Subscribe to Receive Every Issue