© Connecticut Explored Winter 2018-2019

There ought to be a plaque near the corner of Sigourney and Collins streets in Hartford, in the shadow of Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center. And it should read, “Here in 1920 began a performing arts conservatory that is renowned throughout the world.” That conservatory has had several names through the decades, mostly variations of the “Julius Hartt School of Music.” Today, as the Hartt School at the University of Hartford, it is preparing to celebrate its centennial in 2020. From a house on Collins Street, it has grown into a three-building institution where this year about 620 undergraduate and 150 graduate students pursued degrees in music, dance, and theater. They came from around the world, and a few will go on to international fame.

None of Hartt’s success was inevitable.

Dr. Demaris Hansen, professor of music education at Hartt and curator of the Hartt School Centennial History Project, points to the dedication of the school’s founders and earliest supporters who forged onward, despite a host of obstacles, especially a chronic lack of money. “The people who started this school were so driven, and so totally convinced that this was just the way music education should be,” Hansen told me in an interview for this article. “They just drove through all these completely devastating things that could have destroyed the school.”

The story, according to University of Hartford records, begins with Julius Hartt, a Massachusetts native who settled in Hartford after studying piano in Berlin and Vienna. He became organist at Asylum Hill Congregational Church in 1909 and then, in 1914, music editor of the Hartford Times. Along the way, Hartt began teaching a promising young musician named Morris Perlmutter. Born in Hartford to Russian immigrants in 1895, Morris began violin lessons at age 5 but soon switched to piano at Hartt’s urging. By age 15 he was making pocket money by playing at weddings, hotels, and theaters, where he accompanied silent films. In 1912 he made his professional debut at Unity Hall on Hartford’s Pratt Street, playing Beethoven’s “G Major Piano Sonata.” Hartt grew so impressed with his student that he eventually introduced him to esteemed Swiss composer Ernest Bloch, then living in New York City. Bloch afterward wrote, “My friend Hartt has a young pupil of 21 years who is absolutely extraordinary as a musician and pianist. This boy’s name is Morris Perlmutter, and I am convinced he is a real genius…”

In 1918, the same year he joined the faculty of the private Kingswood School and served in World War I as a U.S. Army band sergeant, Perlmutter changed his name for professional reasons to Moshe Paranov. The next year, Hartford residents began seeing advertisements for music lessons by “Julius Hartt, Moshe Paranov, and Allied Piano Teachers.” The lessons were held in Hartt’s home on Sigourney Street. As enrollment grew, the operation moved to bigger quarters around the corner, to a rented house at 222 Collins Street. It also became the Julius Hartt School of Music, with Hartt, Paranov, Samuel Berkman, and Hartt’s daughter Pauline serving as founders. (Pauline, known as Dottie, married Paranov in 1924.)

The school hardly operated in isolation; indeed, Paranov placed himself at the vanguard of the city’s cultural scene. In 1926, with radio still in its infancy, he joined the music staff of WTIC. It was a time when radio stations assembled their own orchestras, and by the late 1930s Paranov was WTIC’s music director. Many of the symphonic and pops programs he conducted on the air were heard across the country, thanks to national network hookups.

When the Bushnell Memorial opened in 1930, the inaugural concert included Paranov conducting the Choral Club of Hartford, the Hartford Oratorio Society, and the Cecelia Club, accompanied by members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

When the Bushnell Memorial opened in 1930, the inaugural concert included Paranov conducting the Choral Club of Hartford, the Hartford Oratorio Society, and the Cecelia Club, accompanied by members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Julius Hartt retired in 1936, and the school was renamed the Julius Hartt Musical Foundation in his honor. The next year, a figure whose importance to the school ranks only behind that of Hartt and Paranov joined the board of trustees. As the “original Fuller Brush Man,” Alfred C. Fuller had made the Hartford-based Fuller Brush Company famous across the nation for its army of door-to-door salesmen; one of Hartford’s business titans, Fuller recognized a kindred spirit in the relentless Paranov, who now was dean of the music school. Their mutual admiration led to Fuller’s becoming Hartt’s chief benefactor during the next several decades.

After surviving the worst of the Great Depression, the school moved in 1938 to much more spacious quarters. Broad Street hadn’t been scarred yet by the construction of Interstate 84; turning onto it from Farmington Avenue revealed two massive examples of Gothic architecture: the Hartford Public High School on the left side of the street and the Hartford Theological Seminary on the right. The seminary had left for new quarters in the city’s West End, so Paranov and company took advantage of the prime location by purchasing the wing of the building known as the Case Memorial Library.

The Hartt School now had two auditoriums—one seating 500, the other 150—along with studios, practice rooms, and offices. “They had a big area on one side of the house where everybody ate together—all the staff, all the faculty, all the students,” Hansen said. “There’s something very special about that.” For the public, 187 Broad Street became a cultural hub. The performances held there were major events, especially when Hartt professor Irene Kahn joined Paranov for a series of acclaimed duo-piano recitals.

Hartt was now on a roll. The state board of education voted in 1940 to allow it to confer Bachelor of Music degrees—a first for any independent institution in Connecticut. Approval to teach music-education courses came shortly afterward. In 1942 Hartt held its first opera production; in 1945 the Hartt Opera Guild was formed.

By the 1950s it became obvious that the Broad Street building could no longer accommodate such growth. The problem, as usual, was money: the school simply didn’t have enough of it to expand. Or, at least not on its own. Eventually a plan emerged to create a university by bringing together three existing schools in the city: Hillyer College (founded as part of the city’s YMCA in 1879), the Hartford Art School (founded in 1877, see “An Art School Forged in the Gilded Age,” Summer 2003; available online), and the Julius Hartt Musical Foundation. When Governor Abraham A. Ribicoff signed legislation approving the merger in 1957, the University of Hartford was born.

By the 1950s it became obvious that the Broad Street building could no longer accommodate such growth. The problem, as usual, was money: the school simply didn’t have enough of it to expand. Or, at least not on its own. Eventually a plan emerged to create a university by bringing together three existing schools in the city: Hillyer College (founded as part of the city’s YMCA in 1879), the Hartford Art School (founded in 1877, see “An Art School Forged in the Gilded Age,” Summer 2003; available online), and the Julius Hartt Musical Foundation. When Governor Abraham A. Ribicoff signed legislation approving the merger in 1957, the University of Hartford was born.

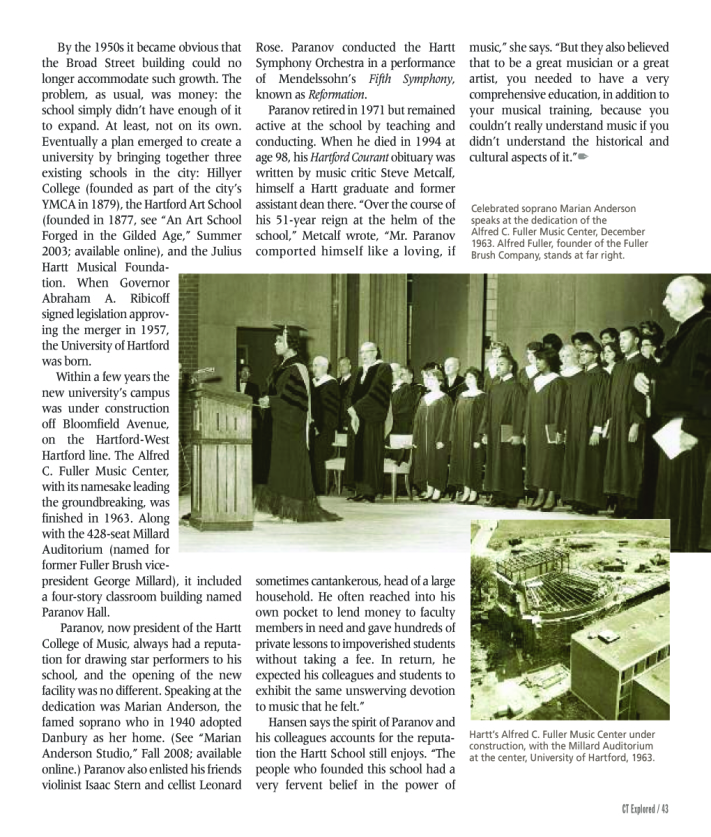

Within a few years the new university’s campus was under construction off Bloomfield Avenue, on the Hartford-West Hartford line. The Alfred C. Fuller Music Center, with its namesake leading the groundbreaking, was finished in 1963. Along with the 428-seat Millard Auditorium (named for former Fuller Brush vice-president George Millard), it included a four-story classroom building named Paranov Hall.

Paranov, now president of the Hartt College of Music, always had a reputation for drawing star performers to his school, and the opening of the new facility was no different. Speaking at the dedication was Marian Anderson, the famed soprano who in 1940 adopted Danbury as her home. (See “Marian Anderson Studio,” Fall 2008; available online.) Paranov also enlisted his friends violinist Isaac Stern and cellist Leonard Rose. Paranov conducted the Hartt Symphony Orchestra in a performance of Mendelssohn’s Fifth Symphony, known as “Reformation.”

Paranov retired in 1971 but remained active at the school by teaching and conducting. When he died in 1994 at age 98, his Hartford Courant obituary was written by music critic Steve Metcalf, himself a Hartt graduate and former assistant dean there. “Over the course of his 51-year reign at the helm of the school,” Metcalf wrote, “Mr. Paranov comported himself like a loving, if sometimes cantankerous, head of a large household. He often reached into his own pocket to lend money to faculty members in need and gave hundreds of private lessons to impoverished students without taking a fee. In return, he expected his colleagues and students to exhibit the same unswerving devotion to music that he felt.”

Paranov retired in 1971 but remained active at the school by teaching and conducting. When he died in 1994 at age 98, his Hartford Courant obituary was written by music critic Steve Metcalf, himself a Hartt graduate and former assistant dean there. “Over the course of his 51-year reign at the helm of the school,” Metcalf wrote, “Mr. Paranov comported himself like a loving, if sometimes cantankerous, head of a large household. He often reached into his own pocket to lend money to faculty members in need and gave hundreds of private lessons to impoverished students without taking a fee. In return, he expected his colleagues and students to exhibit the same unswerving devotion to music that he felt.”

Hansen says the spirit of Paranov and his colleagues accounts for the reputation the Hartt School still enjoys. “The people who founded this school had a very fervent belief in the power of music,” she says. “But they also believed that to be a great musician or a great artist, you needed to have a very comprehensive education, in addition to your musical training, because you couldn’t really understand music if you didn’t understand the historical and cultural aspects of it.”

Kevin Flood is a freelance writer and editor who operates HartfordHistory.net, a website dedicated to the history of Connecticut’s capital city. He last wrote “Almada Lodge and Channel 3 Kids Camp,” Summer 2018.

This is the fourth in a series of stories about the history of nonprofits in the Greater Hartford region, funded in part by the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving.

For more of Connecticut’s musical history, read:

Fall 2008: “And the Beat Goes On”

More related to the University of Hartford, read:

“An Art School Forged in the Gilded Age: the Hartford Art School”

For more in this series, read:

“Preserving Houses of Worship & the Hartford Preservation Alliance,” Spring 2018

“Almada Lodge and Channel 3 Kids Camp,” Summer 2018

“Greater Hartford League of Women Voters,” Fall 2018