Hartford and the Black Panthers

Interview conducted by Joan Jacobs

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2004

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

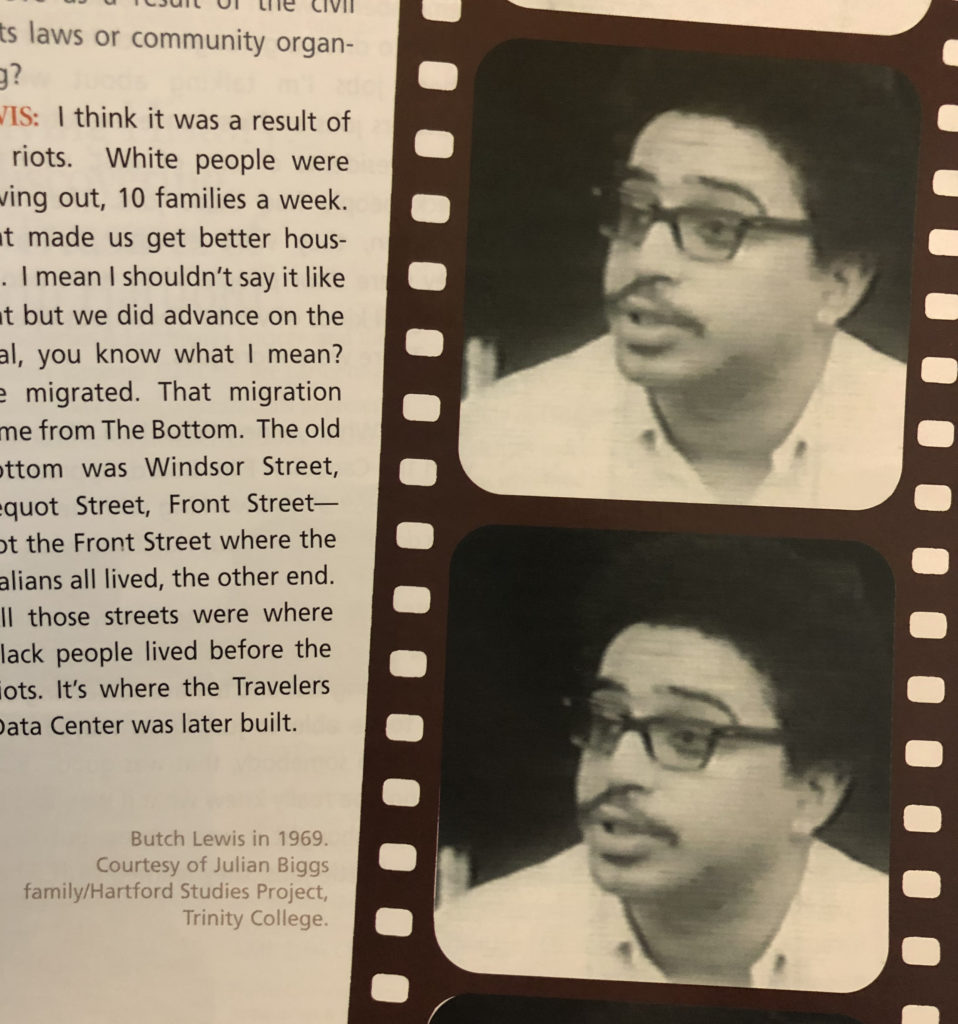

Butch Lewis co-founded the Hartford chapter of the Black Panther Party and was an activist in the late 1960s. He first came to Hartford from Fredericksburg, Virginia in 1956 at age 12 to live with his grandmother. Drafted into the army in January 1965, he served in Vietnam until December 1967. At the time of his release, he was in Oakland, California, birthplace of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. (The name was later shortened to the Black Panther Party.) Although he had no contact with the Panthers in California, he read and was inspired by news of their activities. Upon his return to Connecticut in 1968, he helped organize the Hartford chapter and became its leader. The Hartford group was involved in organizing and demonstrating for improvements in housing, education, and jobs for African Americans in Hartford.

As leader of the Black Panther Party in Hartford, Lewis was contacted by filmmakers from the Film Board of Canada and UCLA who were working on a documentary exploring Hartford as a model city during that era’s “War on Poverty.” When funding ran out, the filmmakers left all of the Hartford footage and equipment with Lewis. Renewed interest in the historic footage spawned a project, coordinated by Professor Susan Pennybacker at Hartford’s Trinity College, to complete the documentary. At the time of the interview, Lewis served as a sexton for the South Congregational Church of Hartford.

I asked Butch to reflect on his experiences working to improve housing, education, and job opportunities for the African American community in the late 1960s.

Jacobs: Bring us back to 1968 and the early days of the Black Panther Party in Hartford. What drew people to the Party?

Lewis: The Party was an organization that people wanted to join because we talked about politics and politicians, we demonstrated, and we helped people in the community. For example, we knew kids were going to school hungry so we started the breakfast-before-school program. That involved getting a place—Father Lenny Tartaglia let us run it from St. Michael’s—and getting people to donate food. We never terrorized anybody; people came and gave us stuff. When the kids wanted to walk out at Weaver high school, we went up to help organize it, and we made sure no one got hurt. I think we became a big brother to a lot of people.

Every time we went and did something we got another member. It wasn’t that hard to get people to come into the Party then because we were more together as a community than we are now. We had meetings in the streets and in an apartment we had on Westland Street. Party membership wasn’t kept on paper. That way no one could raid us and say, “Well, this cat did this, and this person did that.” A lot of people were associated with the Party but didn’t do demonstrations and such. There were a lot of black professionals who helped us out but who didn’t want it known that they did because they were scared about losing their jobs.

Jacobs: How was the Party regarded by outsiders?

Lewis: I think a lot of people were scared of it. We didn’t back down from confrontation; we faced confrontation. Some ministers worried about us…pointed us out to the cops during the riots, told them where we lived.

Jacobs: What were the Panthers doing during the riots [Hartford, like cities across the U.S., erupted in violent protest in the summers of 1968 and 1969]?

Lewis: We were the ones who met with the fire department and made sure they could come into the neighborhood to put out the fires. People were cutting hoses, throwing rocks, taking axes off the trucks. We were the only ones allowed on the street at night without getting arrested

Jacobs: Did you work with other groups in the community?

Lewis: Yeah. You knew everybody, you knew all the different organizations, you worked with the different organizations, you demonstrated with the organizations, you did community work. If somebody was running for office and you felt that this was good for the community, you put your people out and did work for them, but still you were going by the rules of the Black Panther Party.

Jacobs: What other significant organizations were in existence at the same time?

Lewis: The Urban League, The Community Renewal Team, the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee…a lot of the groups coming up from the civil rights movement had offices here. A lot of students from Trinity and the Hartford Seminary, white students, were hooked up with the SNCC and Students for a Democratic Society, left-wing organizations. They were hooked up into the Young Communist Party.

Jacobs: What needed to change in Hartford?

Lewis: Living conditions, the same things as today, the same identical things, it hasn’t moved. Housing, jobs, education.

Jacobs: Did access to housing improve as a result of the civil rights laws or community organizing?

Lewis: I think it was a result of the riots. White people were moving out, ten families a week. That made us get better housing. I mean I shouldn’t say it like that but we did advance on the deal, you know what I mean? We migrated. That migration came from The Bottom. The old Bottom was Windsor Street, Pequot Street, Front Street—not the Front Street where the Italians all lived, the other end. All those streets were where black people lived before the riots. It’s where the Traveler’s Data Center was later built.

Jacobs: Did access to professional jobs for blacks improve?

Lewis: They started opening up more because there were demonstrations at stores downtown, and no one wanted a demonstration in front of their store. The demonstrations were organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Panthers, everybody. Then they started opening up managerial jobs. That created incentive for us to go to college in the sixties. With a college education, you could get a manager’s job instead of sweeping floors.

Black people in the 1960s didn’t have state jobs. You knew how many black people had state jobs and city jobs, too. You remembered when the first black man was hired to drive a garbage truck in Hartford. These jobs I’m talking about weren’t Travelers jobs and insurance executives, no vice presidents or any of that, very few black people had those jobs. They were salesmen, they were elevator operators, they were door people, they were people doing all kinds of work. Those jobs opened up. There were more jobs.

Black people in the 1960s didn’t have state jobs. You knew how many black people had state jobs and city jobs, too. You remembered when the first black man was hired to drive a garbage truck in Hartford. These jobs I’m talking about weren’t Travelers jobs and insurance executives, no vice presidents or any of that, very few black people had those jobs. They were salesmen, they were elevator operators, they were door people, they were people doing all kinds of work. Those jobs opened up. There were more jobs.

Jacobs: When Anne Michaels, a filmmaker with the Canadian Film Board, approached you in 1969 about working with her team on a documentary about Hartford, what did you think?

Lewis: We saw something positive. To live in the sixties, and you look back now, things were moving fast and to have something on film, to be able to just know maybe you could help somebody, that was good. But then no one really knew what it was, and a lot of us thought it was a hoax. But hey, guys got little jobs; they learned stuff. The film crew was here when the shit broke out again [rioting in the summer of 1969]. They were here about six or seven months and then all of a sudden they said, “Hey we have no more money to finish this program.” They left all this equipment. Matter of fact we knew how to run all this stuff because they had taught us. That was one of the agreements; we knew how to run every damn thing there.

Jacobs: What are your thoughts about this moment in history, now that the film footage has been resurrected and the documentary you began more than thirty years ago is being completed?

Lewis: It brings back memories and sadness that a lot of those people have died and everything they fought for still hasn’t materialized and now their children and maybe their grandchildren will have to fight to maybe get it or maybe not get it. That’s the sad part about it. The good part about it is that this could maybe help open our eyes so we don’t go back to where we were because we’re already half way back and don’t realize it.

Joan Jacobs is a member of CT Explored’s editorial board.

Explore!

“The New Haven Black Panther Trials,” Winter 2019-2020

Read all of our stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.