(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

We understand that every seat in Music Hall [in New Haven]was sold for the Jubilee concert last night and when the doors were opened only standing room could be had.… The [Fisk University Jubilee] singers sang well and were warmly encored…. During the evening Rev. Henry Ward Beecher was prevailed upon to make a statement…. He made a good begging speech [and]about $600 were pledged on the condition that $1000 should be raised for the Fisk University.… The singers were not met with ovations when they began their tour. Until they reached New York their expenses exceeded [their fundraising]but the success that now attends their efforts, makes up for past losses. They will probably return and sing here again.

New Haven Register, February 15, 1872

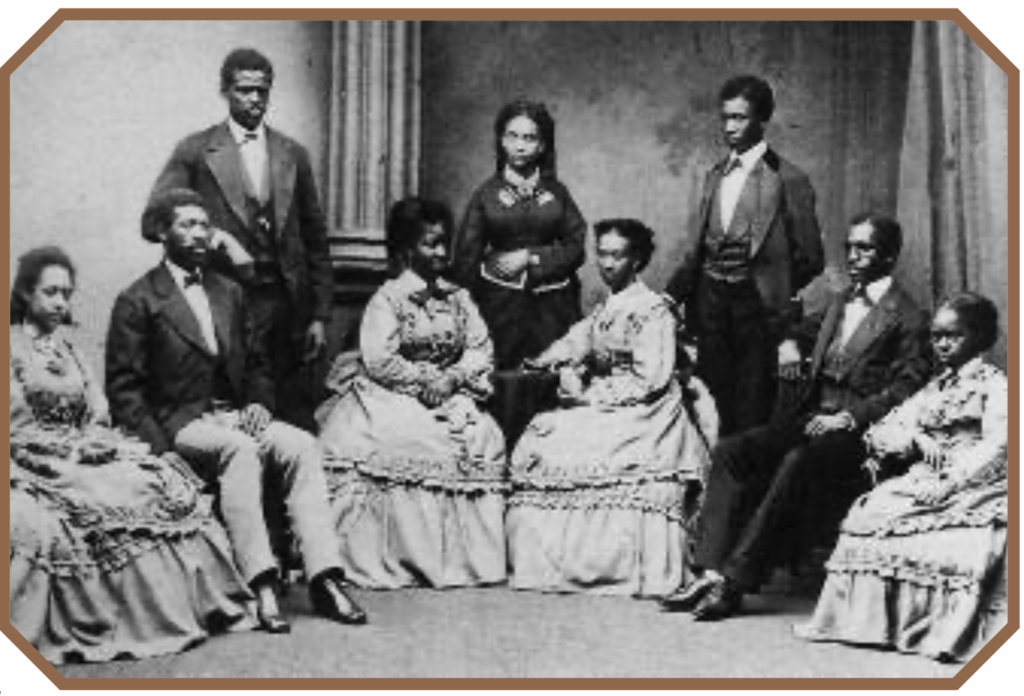

On October 6, 1871—six years after the Civil War’s end—a small group of African-American youth, some recently freed and others born into freedom, began a musical journey from Nashville. The Fisk Jubilee Singers went on tour to raise funds to help settle the school’s debts. Fisk University’s Jubilee Hall is evidence of the tour’s ultimate financial success. While on that tour, the Singers introduced Negro spirituals to a curious American public fascinated by the recently freed Black Americans and their culture. The young singers personified a broader effort to safeguard and raise awareness of the culture free and enslaved Blacks had created while in America. They found support and allies in Connecticut and New England. Their efforts, along with those of other Black performers of the period, helped to focus a movement to resurrect the Black image in late 19th-century America.

The Amistad Center for Art & Culture’s upcoming exhibition War Prizes: The Cultural Legacy of Slavery and the Civil War (opening this fall) recognizes the Civil War anniversary and celebrates the efforts of several generations to promote an accurate understanding of African-American culture from the tumult of the Civil War through Reconstruction and into the 20th century’s freedoms.

Enslaved Blacks created regionally specific cultures adapted to their lives. In places as disparate as Louisiana, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut, Black communities found ways to worship, communicate, cook, and celebrate that were familiar and comforting. While those cultural forms might have been understood and even shared by Blacks and whites in a region, the Civil War brought broader exposure of the cultures and of slavery and other circumstances in those regions—and with it opportunities to exploit political ideology, music, dance, worship style, and even the clothing Blacks favored to both the benefit and the detriment of the enslaved and free. As Democrats and Republicans, Northerners and Southerners, abolitionists and slaveholders, and citizens and immigrants argued the issues that would lead to war, public images of Black life and culture became increasingly politicized—and ultimately reduced to sentimental or mean-spirited stereotypes.

The spirituals sung by the Jubilee Singers were solid cultural forms of African America. The combined musical influences of different continents produced music that entertained crowds of working people at minstrel shows and eventually the elite in concert halls. Arrangements of those songs influenced the African-American composers Charles Albert Tindley, Harry T. Burleigh, and William Grant Still. But before their work reached the concert hall, elements of the music appeared on the minstrel stage in humiliating performances that mocked black people’s speech, intellect, movement, and even style of dress.

The Jubilee Singers and their handlers set off for their first tour in an uncertain environment. Early audiences in Ohio and a few other Northern states received the singers with indifference or even hostility. Some expected they would perform comic and degrading minstrel songs. They made very little money from donations, faced discrimination in their accommodations—when housing could be secured—and struggled to gain support for the tour from a reluctant American Missionary Association.

Their fortunes changed once the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher agreed to support the tour. The Connecticut native was the nation’s preeminent celebrity preacher; by inviting the singers for a December performance at the prestigious Plymouth Church of Brooklyn, Beecher ensured the tour’s success. After the triumph at Plymouth, they received offers from other churches and larger halls, and the American Missionary Association finally agreed to back the tour.

Connecticut dates followed, and the Jubilee Singers received a warm welcome, favorable press coverage, and solidly respectable donations from audiences. They sang in Westport, Farmington, Plainville, Bristol, New Britain, Norwich, and Waterbury. Mark Twain attended one of the Hartford performances and began a long and favorable association with the singers. Their New York and Connecticut dates were a welcome respite from the difficult early tour dates, but there were still complications. The singers stayed at the homes of some of New Haven’s leading citizens after several hotels appeared wary of renting them rooms.

The Connecticut appearances, made profitable by Beecher’s patronage, helped sustain the tour—and the singers. Connecticut press reviews show evidence of an appreciation of the music and the singers’ experience in a way that acknowledged their humanity. In particular, these reviews evaluated the music and performers in comparison to other concert music, not to popular minstrel music. Twain endorsed the Jubilee Singers as a more realistic musical experience—based on his knowledge of the South—than the popular Negro minstrel performances. The tour had many objectives, among which raising money was paramount, but through their music, the Jubilee Singers began to broaden the spectrum of what could be expected of African Americans in the years after the Civil War. Their national tour meant that in many newspapers there was at least one favorable story about Black life and culture while the singers were in town.

Other African-American public intellectuals, performers, and activists would follow the Jubilee Singers’ effort to reclaim and resuscitate representations of Black life and culture in the late 19th century and into the 20th century, though Black artists often struggled to control their creative endeavors and the venues in which they would perform. Through success and failure, the Jubilee Singers’ experience blessed all of these performers by insisting that critics and audiences begin to consider the creative achievements of the then recently freed people. It was a long struggle, but African-American performers’ efforts helped maintain the integrity of a potent cultural form and inspired its use as a tool in later political efforts.

Frank Mitchell was consulting historian for The Amistad Center for Art & Culture.

Explore!

Read more about Connecticut in the Civil War in Spring 2011 and our special issue commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, Winter 2012/2013.

Read more about the African Americans experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.