By David F. Ransom WINTER 2003

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

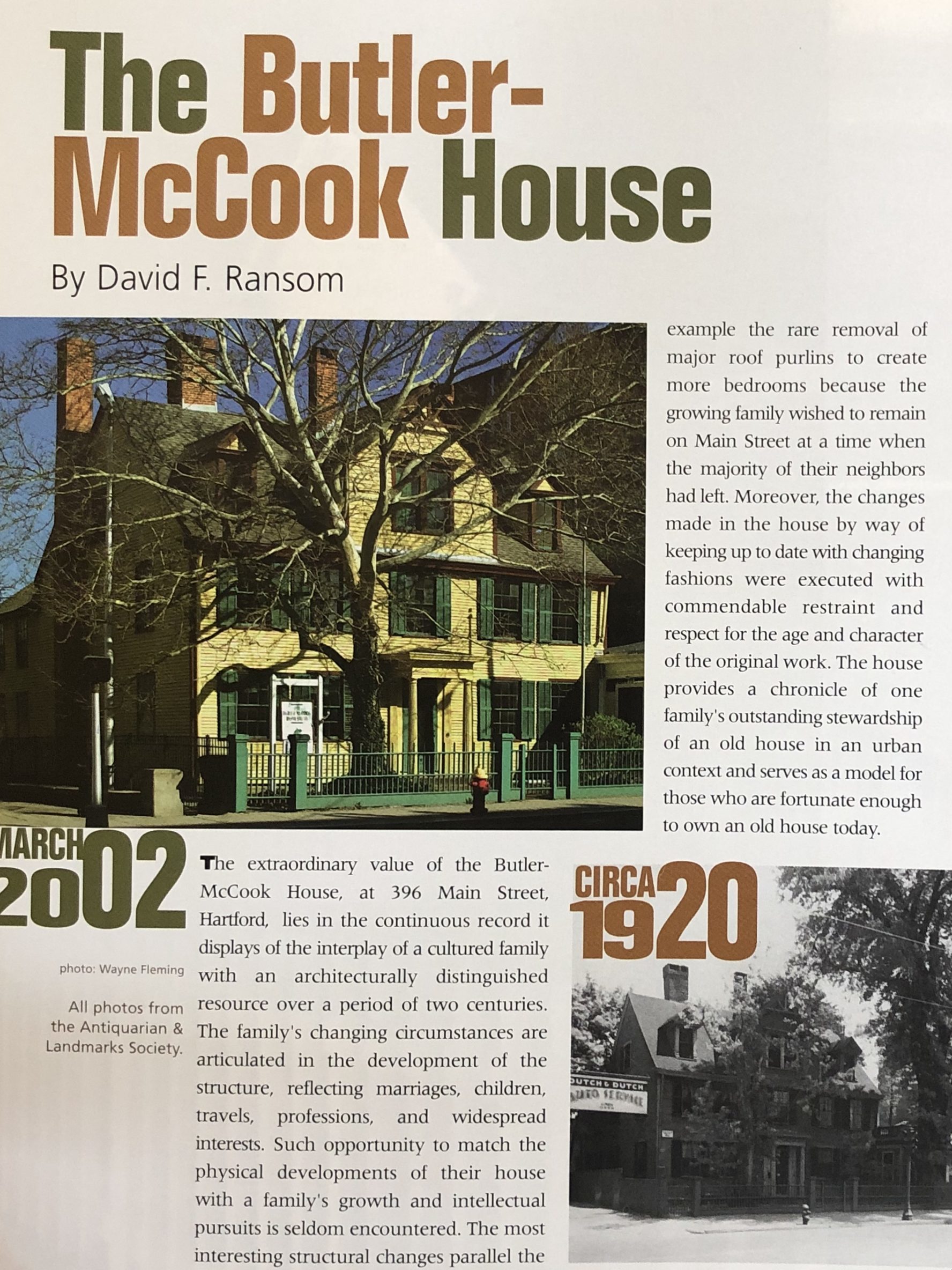

The extraordinary value of the Butler-McCook House, at 396 Main Street, Hartford, lies in the continuous record it displays of the interplay of a cultured family with an architecturally distinguished resource over a period of two centuries. The family’s changing circumstances are articulated in the development of the structure, reflecting marriages, children, travels, professions, and widespread interests. Such opportunity to match the physical developments of their house with a family’s growth and intellectual pursuits is seldom encountered. The most interesting structural changes parallel the most important family decisions, for example the rare removal of major roof purlins to create more bedrooms because the growing family wished to remain on Main Street at a time when the majority of their neighbors had left. Moreover, the changes made in the house by way of keeping up to date with changing fashions were executed with commendable restraint and respect for the age and character of the original work. The house provides a chronicle of one family’s outstanding stewardship of an old house in an urban context and serves as a model for those who are fortunate enough to own an old house today.

THE FAMILY

In 1779 Dr. Daniel Butler (1751-1812) married the widow, Sarah Sheldon Ledyard (1757-1812). Three years later, in 1782, they built their Main Street house on a lot one-quarter of the present size. In the 17th century home lots were laid out running from Main Street back to Prospect Street, but as the community developed these lots were bisected, each half fronting on its own street, and were increasingly used for commercial purposes. By the time the Butlers built their house in 1782 such subdivision was well along south of the Park River.

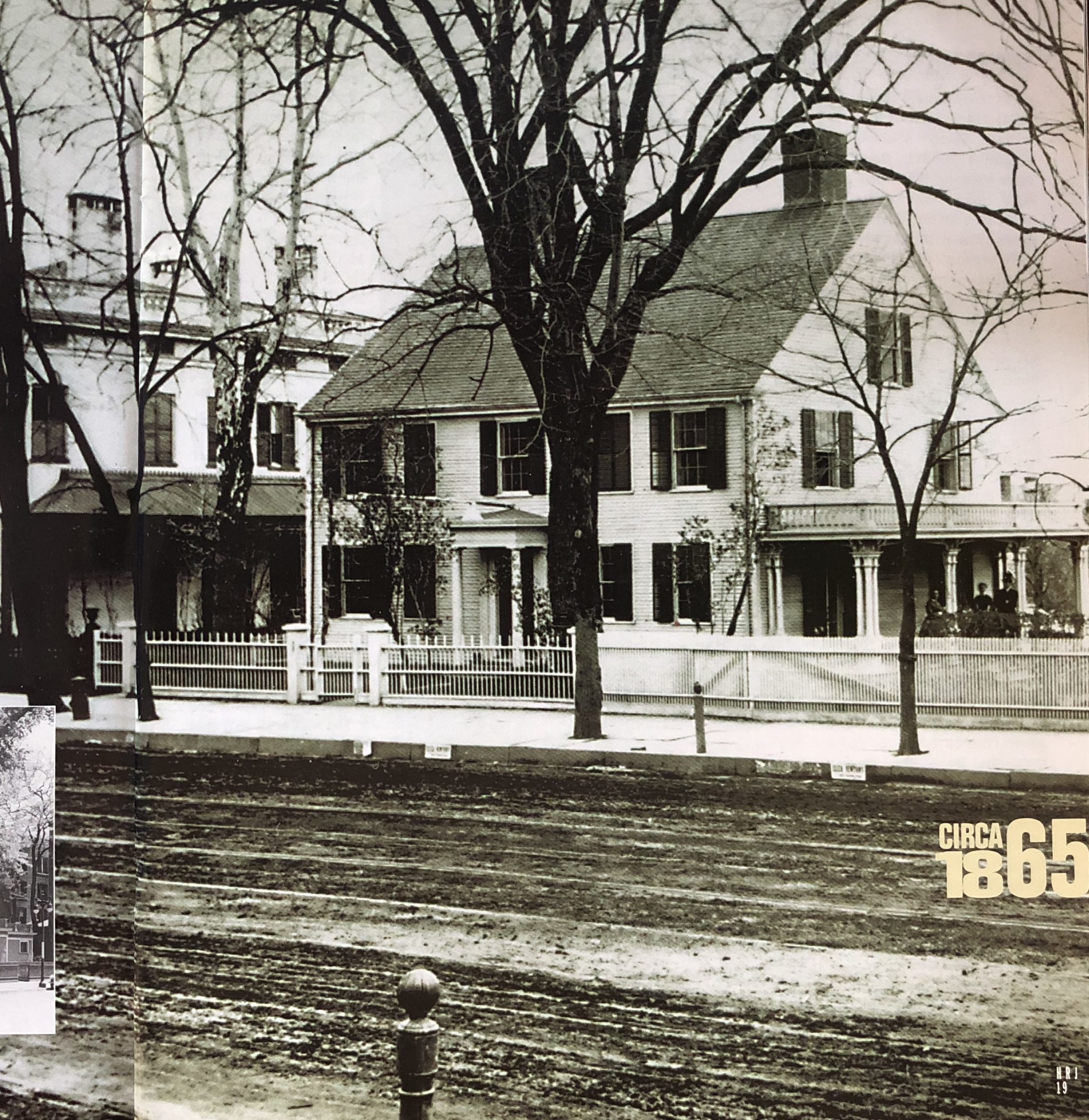

Daniel Butler, in addition to conducting his medical practice, took over the management of mills his wife received in the estate of her first husband. Their son, John Butler (1781-1847), who inherited the house in 1812, continued to operate the mills with great success. Consequently, he had the funds to increase the size of the lot by purchasing, in 1839, a second parcel with frontage on Main Street south of the house, and, in 1845, two parcels with frontage on South Prospect Street, behind the two front lots. By consolidating the four pieces he re-created the wide street-through parcel, but with twice the normal width; his land was twice the size of any other parcel in the block. Butler’s action was an early example of the family’s extraordinary devotion to Main Street.

In 1837, at age 57, John Butler married the widow, Eliza Lydia Royce Sheldon (1797-1858). This event is presumed to have prompted adding the Greek Revival front portico and the Greek Revival fireplace mantels in the north parlor and dining room. John and Eliza Butler had one surviving child, Eliza Sheldon Butler (1840-1917). When John Butler died in 1847 Eliza was seven years old, yet her father’s will named her as chief beneficiary of his estate, which exceeded $100,000. (Butler stipulated that Eliza Lydia would have use of the house during her lifetime.) Improvements to the house soon followed. These included the installation of gas service and such “amenities” as an interior bathroom, a furnace, a cast-iron stove in the kitchen, and a greenhouse in the garden. After John Butler’s death the household consisted of Eliza Sheldon, her mother, Eliza Lydia, and her mother’s daughter by her first marriage, Mary Lydia Sheldon (1816-1887). In 1856 the trio went on a socially de rigeur two-and-a-half-year European Grand Tour. The tour and the activities pursued during the tour by the teenage Eliza set the pattern for the affluent, avante garde lifestyle she followed as an adult.

Eliza Lydia died during the trip and Eliza, age 18, and Mary, age 42, returned to Hartford to resume life on Main Street with three servants. They redecorated, installing fashionable marble mantels, and, most importantly, retaining Jacob Weidenmann (1829-1893), to lay out the famous garden in 1865. The use of Weidenmann’s services was highly unusual in Hartford, and is another example of Eliza’s sophisticated and expensive tastes. During these years a Trinity College student lived in the house as a boarder. He was a cousin of Mary Lydia Sheldon by the name of John James McCook (1843-1927). He and Eliza fell in love and were married in 1866.

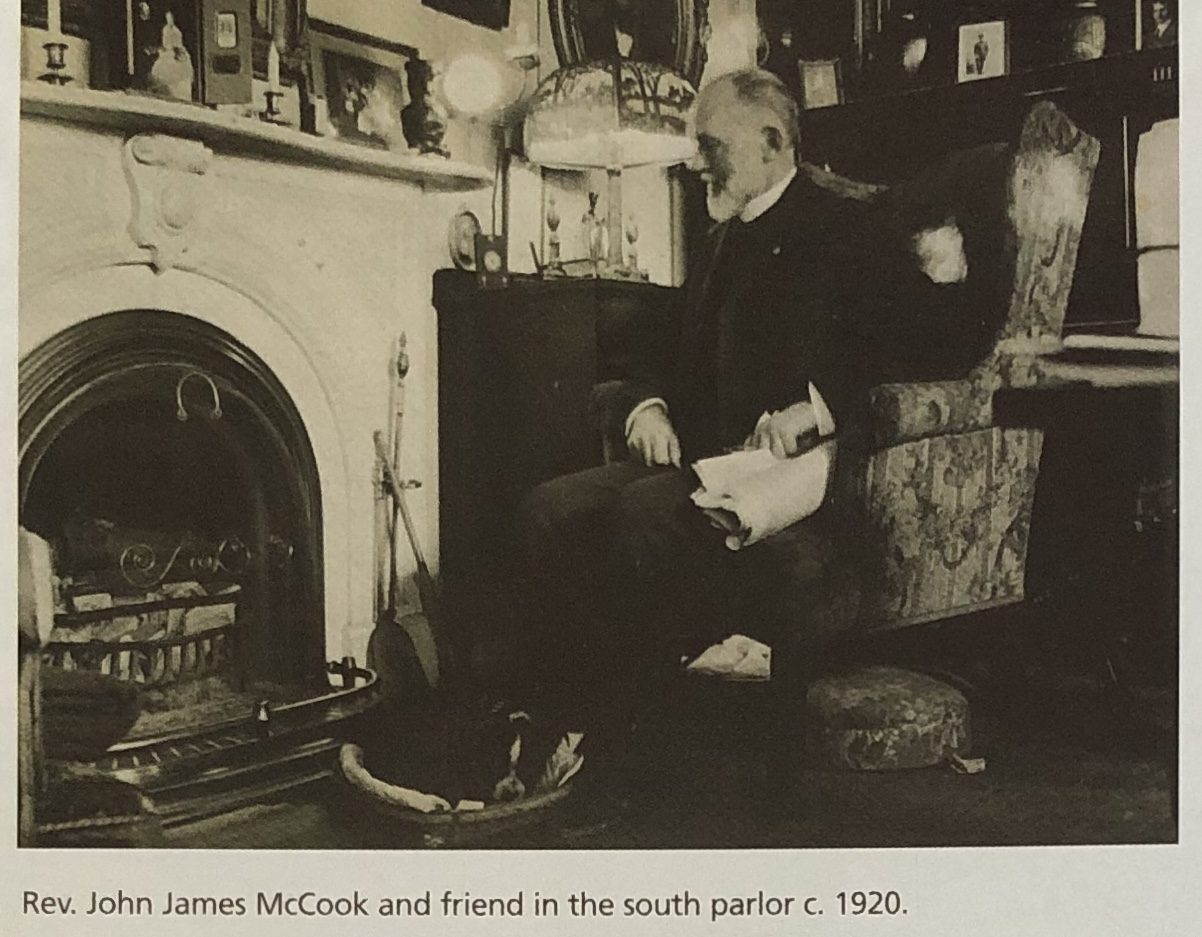

The McCooks led an active, cosmopolitan life. The Reverend John James McCook (as he became) served for 60 years as volunteer rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in East Hartford. He was a member of the Trinity College faculty and was outspoken in public affairs. His indignation over inefficiency in caring for the homeless led to years of work studying the problem and photographing the indigent, an achievement now regarded as seminal in the field. The family, especially John McCook, traveled widely, including a Europe tour in 1874. Many years later, during a nine-month trip around the world (1907-1908) in the company of one of his daughters, John acquired the notable collection of Japanese armor. The McCooks also collected important paintings by artists such as William R. Wheeler and Albert Bierstadt.

The McCooks purposefully stayed on Main Street while others moved to Asylum Hill, a far more fashionable residential neighborhood. Their loyalty to the Main Street location was in marked contrast to their customary observance of social fashion. In 1883 this devotion to the century-old house was reaffirmed by the decision to meet the needs of a large and growing family by adding three bedchambers on the third floor, rather than moving to a larger house. The major addition to the house, the office, was built in 1897 by Dr. John Butler McCook (1867-1946), a son of Eliza and John. It served as a consulting room for his medical practice. He increased its size in 1910, adding a private office and operating room. The Antiquarian & Landmarks Society further increased its size in 2001 for use as exhibition space.

The c. 1950s Colonial Revival remodeling of the kitchen in effect followed the then accepted practice of creating something that never was there but deemed appropriate to the period being revived, and is yet another example of the McCook family’s penchant for being au courant.

The last member of the family to live in the house was Frances A. McCook (1877-1971). She made the doctor’s office space available to the Antiquarian & Landmarks Society in 1965, rent-free. In December 1967 she deeded land at the southeast back corner of the garden to the State of Connecticut, with the stipulation that the Amos Bull House (1788) be moved to the site to become the offices of the Connecticut Historical Commission. Three months later she deeded the entire property, subject to her life use, in trust to the Antiquarian & Landmarks Society. Frances McCook died on March 9, 1971. Soon after taking possession, the Antiquarian & Landmarks Society opened the house to the public and has operated it as a museum ever since.

THE HOUSE EXTERIOR

The Butler-McCook House is a 1782 braced timber framed gable-roofed 32 by 42 foot Federal-style structure with original kitchen ell to the north and turn-of-the-20th-century office addition to the south. The house faces west across from the foot of Capitol Avenue, in downtown Hartford. The .96-acre plot enjoys 118 feet of frontage on Main Street and a depth of 345 feet to South Prospect Street.

In the front of the house, above the low brownstone ashlar foundation, five bays are arranged in a 2-1-2 rhythm, centered on the green paneled front door. An 1837 small Greek Revival portico protects the 1970s door. The siding of the front of the house above the six-foot level is original lapped skived clapboards about four feet long. They are secured by handwrought “rose head” nails. The clapboards, painted a strong gold color with about 3 inches exposed to the weather, flare out as they approach grade. Green sash, probably not original but more likely dating from 1837 alterations, are 6-over-6, made up of larger panes than in the usual 12-over-12 pattern of the period.

In the front of the house, above the low brownstone ashlar foundation, five bays are arranged in a 2-1-2 rhythm, centered on the green paneled front door. An 1837 small Greek Revival portico protects the 1970s door. The siding of the front of the house above the six-foot level is original lapped skived clapboards about four feet long. They are secured by handwrought “rose head” nails. The clapboards, painted a strong gold color with about 3 inches exposed to the weather, flare out as they approach grade. Green sash, probably not original but more likely dating from 1837 alterations, are 6-over-6, made up of larger panes than in the usual 12-over-12 pattern of the period.

Above, in the front slope of the roof, a central cross gable is flanked by two small gable-roofed dormers. The quietly restrained dormers are more in harmony with the historic character of the house than the vigorous cross gable, but the cross gable, marked by its gable-end brace, is more in keeping with architecture fashionable in 1883 when it was added. The cross gable is an indication of the family’s enduring practice of being up to date. Original twin square brick chimneys are located well in from the ends of the house, offset slightly to the rear. A third smaller brick chimney, dating from 1883, rises from the north slope of the cross-gable roof.

The other three sides of the house are similar to the front, being covered in varying mixes of patches of original clapboards and replacements, which often are toward grade. The brownstone foundation continues under the 1782 original front section of the kitchen ell.

The south side elevation of the main block at the front connects to the office addition, but behind the office connection stands the remaining two-thirds of an open side porch designed by Jacob Weidenmann in the Italianate style. It was added in 1865, the same year Weidenmann designed the garden. (Weidenmann was trained in architecture as well as landscape architecture.) Originally, the porch extended all the way to the front of the house, with a balustrade on its roof. In 1939 the porch was enclosed with glazing, making it a sun porch in line with the practice of the times. This change was reversed in 1971.

The office addition to the south is a 43 x 37 foot one-story structure, forming an irregular rectangle in shape. It was built in the Colonial Revival style on brick foundation without basement in 1897 with an addition in 1910. The northerly 1897 portion of the building is frame, covered with galvanized sheet metal clapboards. The office was increased in size by an addition to the south in 1910, to the design of architect Francis E. Waterman (1878-1947). The 1910 primary building material was hollow red terra-cotta blocks covered with the same galvanized sheet metal clapboards as the first section. Small frame additions, front and back, made in 2001 are covered with galvanized sheet metal clapboards, thereby maintaining the historic siding material. The architect for the 2001 work was Roger Clarke.

Several objects and structures are located in the back yard of the Butler-McCook House, in addition to the Weidenmann garden. These include a brownstone reflecting pool; a wooden well house; an antique, round, rotating, unpainted wooden frame for drying clothes; a greenhouse; an 1867 two-story brick carriage house; and, on what was formerly the far southeast corner of the parcel, the Amos Bull House (1788).

THE HOUSE INTERIOR

The front door opens to a central hall with stairway on the left and two rooms on either side. The fluted square newel at the foot of the stair was assembled with hand-headed cut nails; it is dark finished and has an applied half-baluster on the back side. Most doors in the hall are late 18th-century style six-panel doors with the small panels at the top, but the door at the back of the hall, opening onto the kitchen porch, is glazed with Victorian-era tall paired Gothic Revival pointed-arch lights.

In the north front parlor, the best room, windows have distinctive 18th-century double-fold interior paneled shutters, as do all four of the first-floor rooms. In the two north rooms, the parlor and the dining room, each aperture has paired shutters, one over the other, which afforded the option of privacy from the scrutiny of passers-by while at the same time permitting daylight to enter from outside. The Greek Revival-period mantel has an unusual central tablet comprised of horizontally oriented rounded raised ridges and recesses. The firebox is of the Rumford configuration (shallow, with widely splayed stone jambs to throw maximum heat into the room), and is fitted with a coal grate. This was probably rebuilt when the Greek Revival mantel was installed. The walls are plain without chair rail or wainscoting; the taste of the time favored striped wallpaper hung uninterrupted from ceiling to floor. The ceiling is suspended below the summer beam and the corner posts are hidden within the walls. There is no wooden cornice.

top: The best room, the north parlor, with distinctive 18th-century double-fold interior paneled shutters, c. 1970. bottom: South parlor, c. 1910, showing wallpaper, ceiling paper and border, and wall-to-wall carpet. Connecticut Landmarks

The north rear room, the dining room, has a companion Greek Revival mantel and Rumford firebox with coal grate, like those in the parlor, and no paneling or wainscoting.

The south front parlor is finished in a manner more consistent with customary late 18th-century practice. The chimney wall is paneled in the traditional manner and displays a large fielded panel above the mantel shelf. Nineteenth-century modernization includes a Victorian white marble chimney piece and mantel surrounding a coal grate set within the late 18th-century Rumford firebox. The double-fold paneled window shutters are the full height of the window aperture, in contrast to those in the north rooms. The corner posts, which are cased with beaded boxing, show in this room, but the summer beam does not.

The south rear room was converted from a downstairs bedchamber into a library for John J. McCook when he joined the family. Books are shelved in glazed bookcases recessed into what remains of the original 18th-century paneled fireplace wall, on either side of the marble mantel. These changes probably all occurred at one time, c. 1866, when the marble mantels replaced their predecessors.

The kitchen is in the original front section of the ell. Its west wall, including the door to the rear stair, appears to be original to 1782. Its east wall is largely occupied by a large brick fireplace of 18th-century dimensions and configuration, complete with bake oven to the right and surrounding paneling. The ceiling exhibits exposed joists all constructed in the c. 1950s Colonial Revival period, or later.

On the second floor the south front room is the master bedchamber. The fireplace wall of the master bedchamber is entirely paneled from floor to ceiling, topped by an ogee crown molding, all original and in splendid condition. Small panels at the top of the paneling follow the late 18th-century convention. The mantel is white marble. Paneled wainscoting runs around the other three walls. The room as a whole is remarkably well preserved.

The south window in the south rear bedchamber at one time was converted to French doors to provide access to the roof level of the 1865 verandah below, for use as a sleeping porch. The arrangement of having the 1865 porch glazed as a sun porch and its upper level used as a sleeping porch again demonstrates the McCooks’ continuing recognition and adoption of contemporary trends, this time participating in the popular perception, in vogue during the teens and 1920s, of the health benefits derived from outdoor living.

In the 1883 conversion of the attic to living space, light was provided to the front by the new cross gable and two flanking dormers and to the rear by a shed-roofed dormer. Three bedchambers were established across the front, with the rear space devoted to a hall at the top of the new stairway; a bathroom to the south, which

still has its original sheet metal bathtub and a shaving brush; and a storeroom to the north. The three front bedchambers have wood mantels. The north and south bedchambers have the dormers, and the fireplaces in these rooms use the original twin chimneys. The fireplace of the central bedchamber, under the cross gable, required installation of the new small chimney, which rises from the north slope of the cross gable, an expensive innovation to construct. Roof framing was built with rafters and purlins but no ridgepole. In the 1883 alterations the front purlin was removed in order to provide required bedchamber ceiling height, and most of the rear purlin was removed. Wide roof boards visible in the garret appear to be original.

On August 4, 2002, a sport utility vehicle traveling east on Capitol Avenue at a high speed crossed Main Street and crashed into the front of the Butler-McCook House. The vehicle actually entered the house, taking down the south column of the front porch. Damage was extensive but the overall structure held together, probably due in part to the basic post-and-beam construction and in part to the extensive shoring up done over the years in the basement. Furniture, musical instruments, some of the Japanese armor collection, and other irreplaceable items were destroyed. Structural repairs are ongoing, and are expected to be completed by early summer 2003.

In 2002 the Antiquarian & Landmarks Society gave a new name to the office built by Dr. John McCook. It became the Main Street History Center. The former office is now an 1100 square-foot display area that features photographs, objects, and papers from the McCook family collections, and photographs and memorabilia of this historic Main Street neighborhood. These give a compelling experience of the Butler-McCook house, the family’s presence in the house, and the participation of the house and family in the history of the City of Hartford.

David F. Ransom is an architectural historian who has taught “Hartford Architecture” at Trinity College. As a consultant on rehabilitation of historic buildings, he numbers among his recent Hartford projects the G. Fox Building, the Sage-Allen Building, Mortson Street, and Deerfield Avenue.

All photographs from Connecticut Landmarks.

Explore!

Connecticut Landmarks operates five historic sites across the state. Find out more at ctlandmarks.org

Saving Hartford’s Amos Bull House, Summer 2015

Destination: Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden, Summer 2008

Caroline Ferriday & Her Infinitely Generous Family, Fall 2019

Caroline Ferriday: A Godmother to Ravensbruck Survivors, Winter 2011/2012

City, Country, Town: Connecticut Landmarks, Summer 2010

A Love Story at the Palmer-Warner House, Fall 2019