(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2004/2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

All images courtesy of the Shepard M. Holcombe Archives, Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts

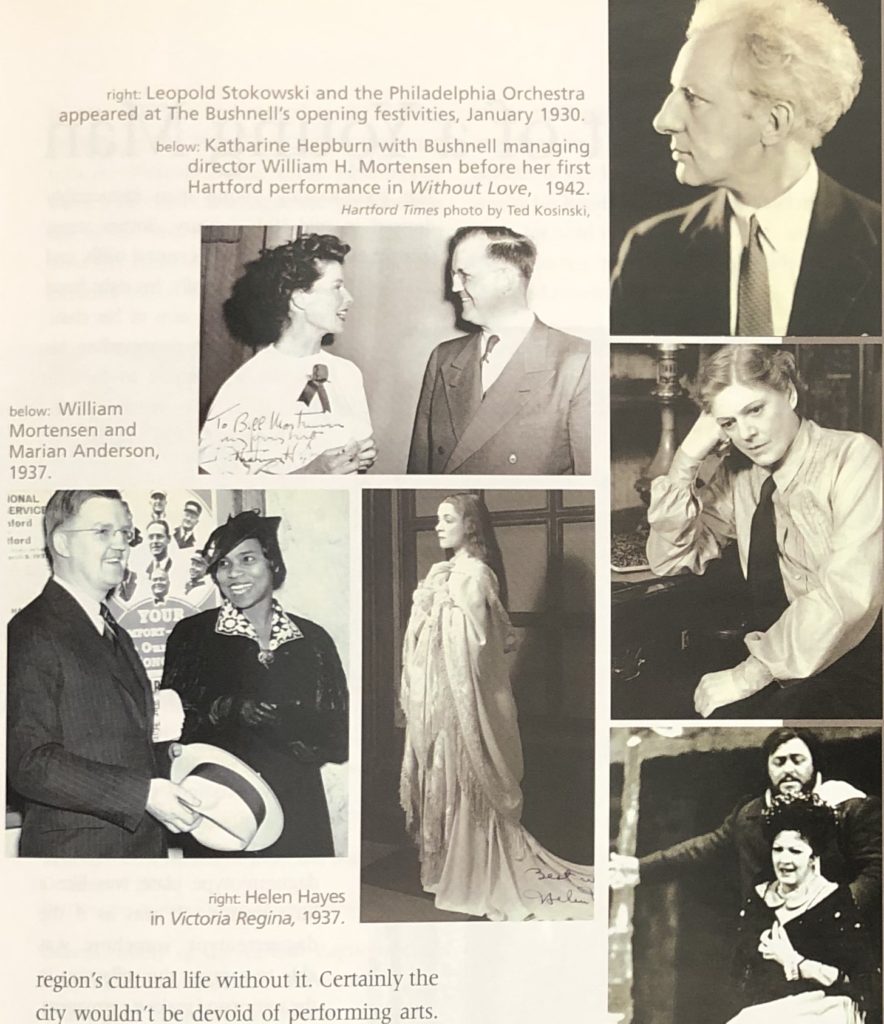

On the evening of January 15, 1930 a three-day-long dedication of The Horace Bushnell Memorial Hall culminated with a performance by the Philadelphia Orchestra led by the legendary Leopold Stokowski, who pronounced the building a uniquely fine performing venue, better than anything in the United States and “much more beautiful and much more satisfactory from the acoustic standpoint than any auditorium in … any foreign city.” For the evening Stokowski graciously yielded the conductor’s baton to an associate, Ossip Gabrilowitsch, Mark Twain’s son-in-law. The program consisted of the Meistersinger Overture, Schumann’s Concerto in A Minor, Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony, and, for an encore, Brahms’s Academic Festival Overture.

Since that sparkling dedication, The Bushnell has hosted more than 4,000 events, many featuring nationally and internationally renowned performers. If importing talent to Hartford was all The Bushnell had to its credit, is impact on the state’s cultural life would have been significant, but since the 1940s The Bushnell has also been the performing home for two pillars of Hartford culture: the Hartford Symphony Orchestra and the Connecticut Opera. It also hosted the now-defunct Hartford Ballet, smaller performing ensembles such as Chamber Music Plus and, presently, the New World Trio (formerly the New World Chamber Ensemble). The Bushnell continues to maintain connections with local schools, companies, and civic organizations to stage their events.

The Bushnell was named for the Litchfield native who served as pastor of Hartford’s North Congregational Church from 1833 until 1851. An influential figure in 19th-century American religion, Reverend Horace Bushnell was also a fervent crusader for improvements to his adopted city. The project dearest to his heart was the creation of a grand public park to replace a slum and an unsightly industrial area near the city center along the banks of the polluted Hog River. Thanks to Bushnell’s advocacy, the city of Hartford purchased the land in 1854, and the nation’s first municipally funded park was completed about 1867. In 1876 Hartford’s Common Council voted to name the new park after the man who had conceived it. Two days later, Bushnell died.

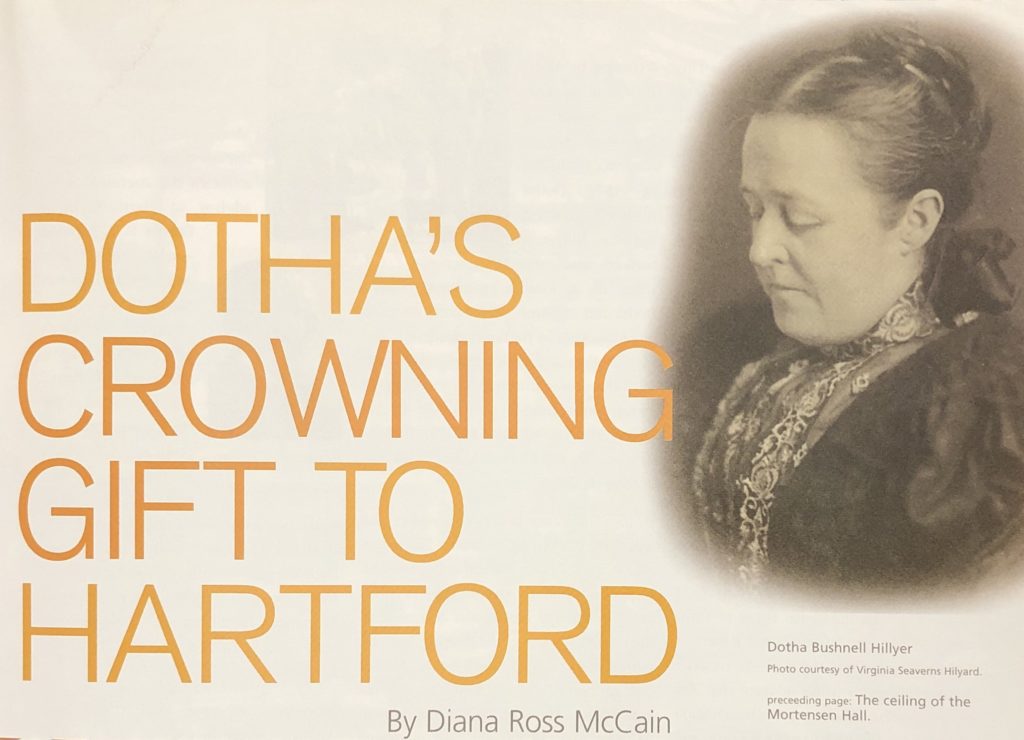

It was a fitting tribute, but Bushnell’s youngest daughter, Dotha, envisioned something more splendid to commemorate her father: “a gracious architectural memorial… a seat for the expression of the educational, cultural and civic ideals which moved the celebrated pastor, and a crowning gift of love to a city long dear to her large heart,” according to Albert W. Coote in Four Vintage Decades: The Performing Arts in Hartford, 1930-1970. In 1879 Dotha Bushnell married Appleton Hillyer, a banker and the scion of a locally prominent family. Dotha and Appleton Hillyer were generous philanthropists in Hartford, giving to a host of institutions and groups, but it wasn’t until 1919 that Dotha Bushnell Hillyer finally set about constructing her memorial to her father. She set up an $800,000 trust to construct the hall that would join the park in bearing his name.

By then Hillyer was in her late seventies and was soon stricken by a chronic illness that incapacitated her for the rest of her life. This sorrowful cloud proved to have a silver lining in that the project was delayed until the economic boom of the Roaring Twenties more than tripled the funds Hillyer had earmarked for her father’s memorial auditorium. Fortuitously, the trust, grown to more than $2,500,000 was liquidated when the cornerstone was laid in 1928 — just a year before the stock market crash plunged the United States into the Great Depression and wiped out investments that likely would have included the funds intended for The Bushnell.

The second bit of good luck was that the 1920s also witnessed the maturation of the man who would bring to fruition Hillyer’s dream in a more splendid way than she had originally conceived. William H. Mortensen (1903-1990) was born in Hartford to Danish immigrants. After graduation from Hartford Public High School he attended Antioch College in Ohio for two years, but the education that mattered most in his life he secured informally.

Mortenson, an unusually intelligent and curious teenager, attracted the attention of his advisor at Hartford High, Charles F. T. Seaverns — who taught Latin and German and was married to Dotha Bushnell Hillyer’s only child, Mary — and of Howard Bradstreet, head of the city’s Americanization program, for which Mortensen worked part time. Charles and Mary Seaverns were members of The Bushnell’s founding board, and through their interest and that of Bradstreet (who had become Mortensen’s mentor) Mortensen found himself rubbing elbows with — and learning a great deal from — the city’s elite.

Mortensen returned to Hartford from Antioch College in 1923 to take a job at Aetna. But he was soon sidetracked from that career path when Charles and Mary Seaverns, impressed by his talent, his passion, and his precocious level of responsibility and trustworthiness, asked him to undertake background research for the auditorium Mary’s mother dreamed of but was no longer physically capable of seeing through to completion. In 1927 Aetna President Morgan Brainard granted Mortensen a leave from his insurance job. Mortensen never went back.

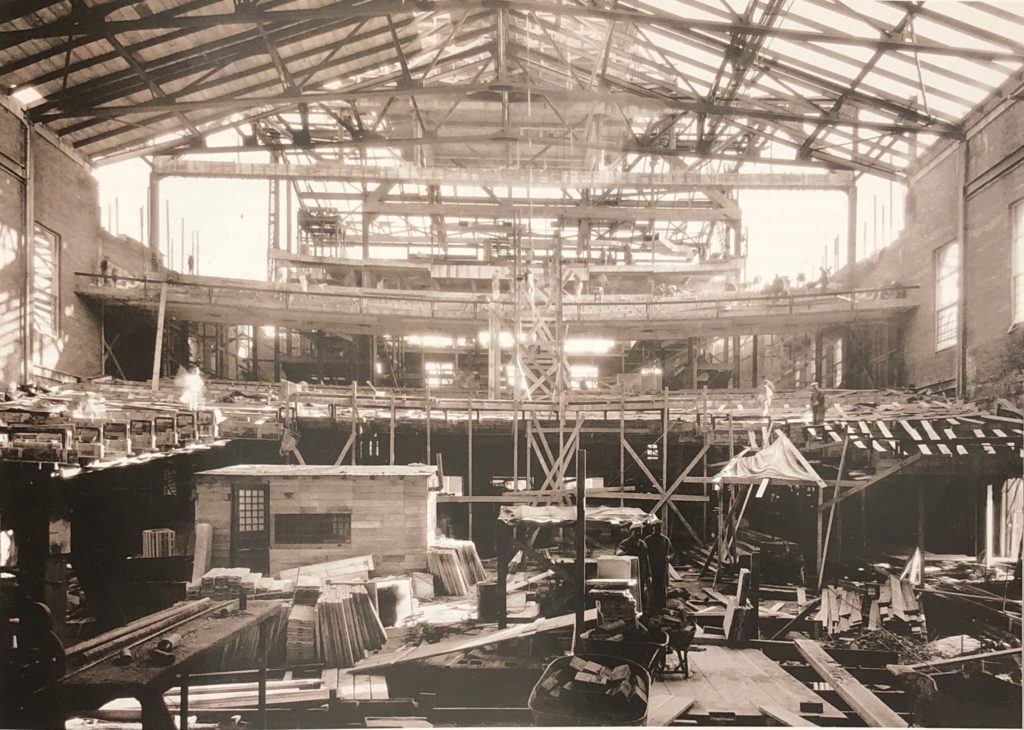

The Bushnell under construction, 1929. Shepherd M. Holcombe Archives, Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts

Mortensen soon found himself immersed in planning a different building than that which Dotha Hillyer, a child of conservative 19th-century Connecticut, had envisioned: “a conventional New England hall, with moveable seats, flat floor and church-type squared balcony,” according to Coote. With greater funds to work with and taking into consideration his patron’s 19th-century New England taste, his own 20th-century ambitions and his “field” research in which he had toured halls as far west as Minneapolis, Mortensen conceived of a facility much more modern and daring. He opposed the flat floor and movable seats and favored a hall that would seat fewer than 4,000. Working with the New York firm of Corbett, Harrison & MacMurray (which was one of the firms that a few years later designed Rockefeller Center), Mortensen succeeded in realizing a building that, Janus-like, looked both forward and backward simultaneously.

The Georgian Colonial exterior of The Bushnell echoes the greatness of Hartford’s heritage as expressed in two of its signature buildings. Its gold dome mirrors the much larger one atop the exuberant High Victorian Gothic Connecticut State Capitol across the street, while its red brick walls and pillared porticos quote the dignified 1796 Old State House not far away on Main Street.

While the outside of The Bushnell pays homage to the past, the interior is a bold expression of the Art Deco style that was avant-garde in the early 20th century. Decorated in shades of magenta, gold, and gray, the interior walls “carry a distinctive geometric fretwork of Islamic design,” according to a 10th anniversary publication.

The interior, the Hartford Courant noted in 1930, “has been described as ‘modernistic,’ but if that be the correct word of description, it should not be taken in its popular sense as bizarre or uncouth. It is not flamboyantly ornate, neither is it bare of color and ornamentation. It is on the contrary a study in rich and artistic color effects carried out in an harmonious artistry, which will undoubtedly be better understood and better appreciated as time goes by.”

Overarching the 2,800-seat auditorium is a mural painting with the Muse of Drama at its center, surrounded by images representing what the Courant called “the changing concepts of musical expression brought to bear upon her by the radio, motion pictures, the finer aspects of music and the popular craze for jazz.” The artist was Barry Faulkner, a well-known muralist of the time who worked on cathedrals in the United States, Canada, and Europe as well as the Cunard Building in New York City. He was assisted by three Prix de Rome artists.

Delighted with Mortensen’s pivotal role in making The Bushnell a reality, in 1929 the board of directors offered him the position of managing director. Mortenson was just 25 years old. It was an inspired, if audacious choice – and the right one. For nearly 40 years, until his retirement in 1968, Mortensen guided The Bushnell with a sure hand, nurturing it into the city’s foremost venue for the performing arts. During that time the indefatigable Mortensen also served a term as mayor of Hartford, from 1943 to 1945.

The Philadelphia Orchestra’s dedication performance, requested by Dotha Hillyer though she was too frail to attend, kicked off a tradition of classical music performances by the foremost orchestras and individual artists that endures to this day. Bushnell audiences have thrilled to the genius of violinists Isaac Stern and Yehudi Menuhin, pianists Vladimir Horowitz, Artur Rubinstein and Van Cliburn, and to the grandeur of performances by the Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and the Rochester symphonies – as well as The Hartford Symphony and its guest starts. Stokowski led the Philadelphia Orchestra in a return visit to The Bushnell in October 1930, while Sergei Rachmaninoff, Arturo Toscanini, Sergei Koussevitzky, and Leonard Bernstein have all raised the baton on the Bushnell stage.

Magnificent vocal music has filled the hall from the beginning. A performance by Paul Robeson marked the Bushnell’s first anniversary in 1931. Great operatic talents Marian Anderson and Beverly Sills have appeared. In 1971 Anna Moffo and Luciano Pavarotti headlined the Connecticut Opera production of La Boheme. Bushnell audiences have savored the sass of Pearl Bailey and the soul of Ray Charles and James Brown. That “popular craze for jazz” noted by the 1930 Courant writer proved to be no passing fad, as performances by Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, Sarah Vaughn, and Louis Armstrong attest. The Bushnell continues to keep pace with revolutionary changes in popular music.

Dance, extraordinarily international in scope, has graced the Bushnell stage ever since Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn took the stage on New Year’s Eve, 1930. Classical ballet performed by Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Les Grand Ballets Canadiens de Montreal, and Ballet Español have appeared. The Hartford Ballet premiered the holiday classic, The Nutcracker, in 1966 and over the course of the next 37 years, Hartford Ballet and its successor, Dance Connecticut, staged more than 60 performances at The Bushnell. Beyond classical ballet, The Bushnell has presented folk dancing from Russia, Senegal, Brazil, India, and Tahiti, and modern dance by the Martha Graham Dance Company, Pilobolus, and Momix.

Great dramatic productions have included Orson Welles’ famous anti-fascist, modern-dress version of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in 1938 (Welles played Brutus), and Paul Robeson returned in 1944 to star in Othello with Jose Ferrer. Katherine Hepburn appeared in 1942 in Without Love, written by Philip Barry, author of The Philadelphia Story. Upon seeing the hall for the first time from the stage, Hepburn exclaimed to Mortensen, “My God, what a barn!” A 1946 production of Antigone featured an obscure 22-year-old Marlon Brando, one year before he shook the acting world to its foundation with his Broadway performance as Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee William’s A Streetcar Named Desire. The WPA’s Federal Theater Project staged One Third of a Nation in January 1939 with a combined cast of Hartford’s Negro and White companies [see also “From Fields to Footlights” in the May/Jun/Jul 2004 issue].

As with music, The Bushnell has adapted its theatrical programming to keep abreast of the changes — sometimes quantum leaps — in American taste and culture. The change over the course of seven decades is at times mind-boggling. In 1937 Hellen Hayes appeared in Victoria Regina; 65 years later The Bushnell presented The Vagina Monologues. Tallulah Bankhead took the stage in Lillian Helman’s The Little Foxes in 1940; CATS was a highlight of the 2004 season.

At its diamond jubilee, The Bushnell, rechristened the Bushnell Center for the Performing Arts in 2001 with the addition of the 900-seat Belding Theater, is charting its future with the same kind of grand vison and imagination that first brough it into existence. That course involves a sea change in its artistic role, from being solely a presenter to being a producer. This will involve collaborations, sometimes international in nature, with other performing arts venues.

Perhaps the best way to assess The Bushnell’s impact on the Greater Hartford arts scene is to try to envision the capital region’s cultural life without it. Certainly the city wouldn’t be devoid of performing arts. But without a major, permanent venue dedicated to offering a broad range of first-rate performances and lending a hand to local groups, professional performances of classical and popular music, theater, humor, and much more would be rare treats in the capital city. Instead, thanks to Dotha Bushnell Hillyer’s generosity, William Mortensen’s managerial and entrepreneurial genius, the steadfast support of the Seaverns family, and the backing of countless additional friends, residents of Greater Hartford and beyond can feast on a bountiful smorgasbord of artistic fare.

Diana Ross McCain is a freelance historian who has been researching and writing about Connecticut’s past for more than 20 years.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s Art History on our TOPICS page.