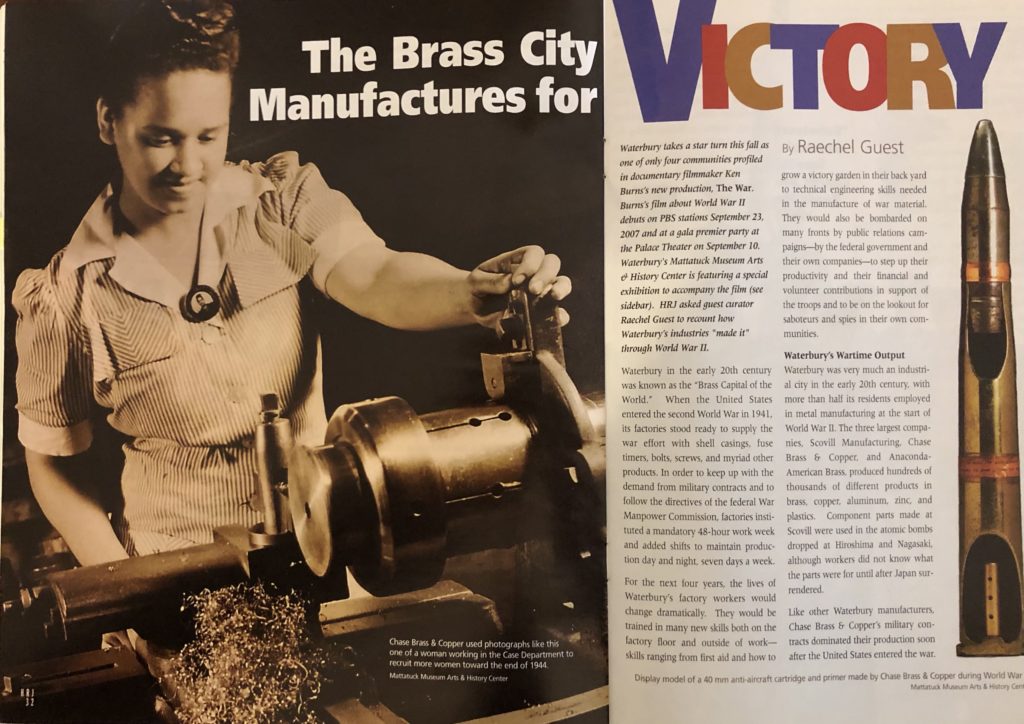

Recruiting photo, Chase Brass & Copper, late 1944. Right: World War II display model, 40 mm anti-aircraft cartridge and primer, Chase Brass and Copper. Mattatuck Museum

By Raechel Guest

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Waterbury takes a star turn this fall as one of only four communities profiled in documentary filmmaker Ken Burns’s new production, The War. Burns’s new film about World War II debuts on PBS stations September 23, 2007 and at a gala premier party at the Palace Theater on September 10. Waterbury’s Mattatuck Museum Arts & History Center is featuring a special exhibition to accompany the film (see sidebar). HRJ asked guest curator Raechel Guest to recount how Waterbury’s industries “made it” through World War II.

Read more about Connecticut in World War II in our Fall 2020 special issue commemorating the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II.

Waterbury in the early 20th century was known as the “Brass Capital of the World.” When the United States entered the second World War in 1941, its factories stood ready to supply the war effort with shell casings, fuse timers, bolts, screws, and myriad other products. In order to keep up with the demand from military contracts and to follow the directives of the federal War Manpower Commission, factories instituted a mandatory 48-hour work week and added shifts to maintain production day and night, seven days a week.

For the next four years, the lives of Waterbury’s factory workers would change dramatically. They would be trained in many new skills both on the factory floor and outside of work – skills ranging from first aid and how to grow a victory garden in their back yard to technical engineering skills needed in the manufacture of war material. They would also be bombarded on many fronts by public relations campaigns – by the federal government and their own companies – to step up their productivity and their financial and volunteer contributions in support of the troops and to be on the lookout for saboteurs and spies in their own communities.

Waterbury’s Wartime Output

Waterbury was very much an industrial city in the early 20th century, with more than half its residents employed in metal manufacturing at the start of World War II. The three largest companies, Scovill Manufacturing, Chase Brass & Brass & Copper, and Anaconda American Brass produced hundreds of thousands of different products in brass, copper, aluminum, zinc, and plastics. Component parts made at Scovill were used in the atomic bombs dropped at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, although workers did not know what the parts were for until after Japan surrendered.

Like other Waterbury manufacturers, Chase Brass & Copper’s military contracts dominated their production soon after the United States entered the war. In October 1942 Chase reported that 92% of its output was munitions. Waterbury Tool was praised in August 1945 by the Navy for supplying sturdy and reliable hydraulic equipment for submarines. Metal component parts made by all of Waterbury’s factories were used in airplanes, ships, tanks, and other military vehicles; a B-29 plane alone contained 3 tons of copper and brass as noted in the October 14, 1944 issue of the company’s Chase News.

Fuses were also a significant Waterbury product during the war. They had been produced by Scovill Manufacturing, Waterbury Clock Company, and other companies during the First World War and were produced again during World War II. Scovill received its first order for 15,000 M-54 “Time and Superquick” 25-second fuses on May 7, 1940 – long before the United States entered the war. The first batch wasn’t finished until December 1941 – just as the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor – because their lightweight aluminum bodies required modifications of the forging process. Soon after the declaration of war, Scovill began producing M-54 fuses at a rate of 30,000 per day.

Workers Step It Up

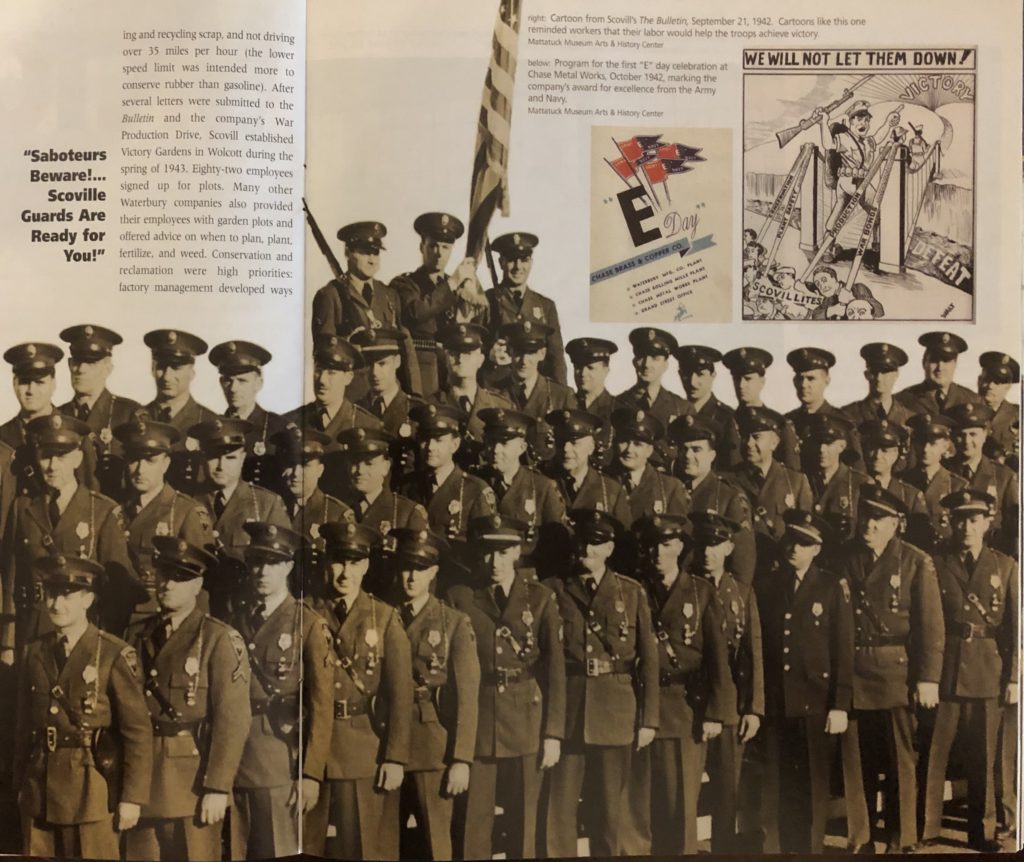

In preparation for war, in 1941 factory workers were given the opportunity through the United States Office of Education’s National Defense Training Program to enroll in engineering courses at Yale University and New Haven Junior College. Some workers enrolled in courses preparing for civilian defense, including learning standard Red Cross first aid. By February 9, 1942, more than 100 Scovill employees had volunteered to serve as roof watchers on the main plant’s eight lookout stations. Scovill guards received training as special duty sheriffs to combat potential saboteurs and were issued riot guns. The August 31, 1942 Scovill’s The Bulletin featured a full-page photo spread showing the guards training with the New Haven County Sheriff’s department on August 6; the headline read “Saboteurs Beware!” … Scovill Guards Are Ready For You!”

Top right: cartoon from Scovill’s “The Bulletin,” September 21, 1942. inset left: Program for the first “E” day celebration at Chase Metal Works, October 1942, marked the company’s award for excellence from the Army and Navy. Bottom: Security guards, Waterbury Tool Company, 1942. Mattatuck Museum

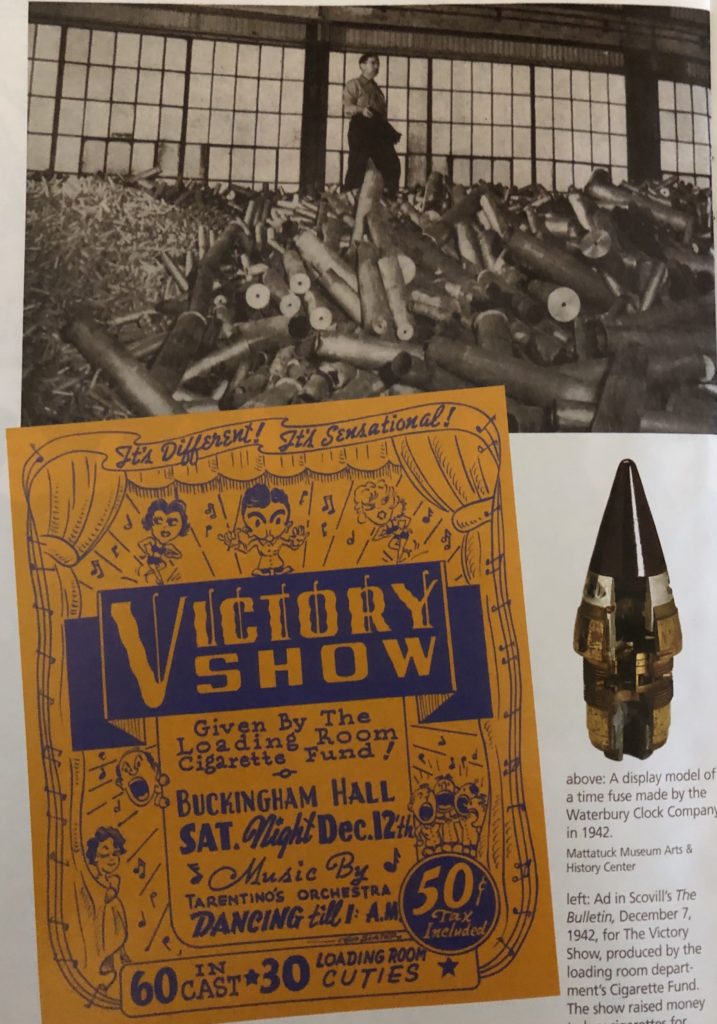

Public relations campaigns within the companies geared up to ensure employee enthusiasm and spur greater productivity. The Bulletin, published weekly by the Scovill foremen’s association, maintained an upbeat, inspirational, and motivational tone throughout the war, celebrating every contribution to the war effort, no matter how small. A front-page article in the December 15, 1941 issue, the first issue to be written after the attack on Pearl Harbor, urged employees to remain calm, while the editorial cartoon showed a Scovill factory supplying Uncle Sam with the military power needed to attack Japan (with the caption “OK – They Asked For It!”). By 1944, Scovill’s The Bulletin, the Chase News, and the Waterbury Tool Watco News, had all run photographs of enormous piles of used shell casings that had been returned in order to be melted down and remade into more shell casings. Photo captions included inspirational lines such as “Most of the larger ones… were used in actual battle and played a big part in starting the enemy on the run for home. To the boys on the war fronts: Don’t worry – there’s more where these came from!

Workers were exhorted to give more than their best and graphically cautioned that any inferior product could cost the life of a serviceman. Factory newsletters were filled with cartoons depicting absenteeism as a detriment to the war effort.

The Chase Metal Works plant implemented an employee award plan in 1944, setting up boxes with the slogans “Uncle Sam needs your suggestions!” and “Think for Victory!” and offering $5 and a War Production Board certificate for a winning idea.

The Navy, and later the Army, began using the letter “E” in 1906 as a mark of excellence awarded to factories that “showed excellence in producing ships and equipment and materials.” Nearly all of Waterbury’s factories received the “E” award at least once; the larger companies earned the award several times. At the celebration marking Chase Brass & Copper’s first “E” Day, on October 15, 1942, Reid Robinson, vice president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and president of International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers, led the gathered employees in a Pledge of Labor: I pledge my mind, my hands, and my heart to our War Production Dive. I will work to increase the production of brass and copper products, so that our Army and Navy can have the weapons to fight with, to bring victory for us all.

Sacrificing for the War

Workers were encouraged to save, scrimp, and ration on and off the job. [See also, “If You Don’t Need It, Don’t Buy It!” 2003 Nov/Dec/Jan 2004.] Scovill’s The Bulletin regularly featured short articles and cartoons repeating the necessity for home gardens, gathering and recycling scrap, and not to drive over 35 miles per hour (the lower speed limit was intended more to conserve rubber than gasoline). After several letters were submitted to the Bulletin and the company’s War Production Drive, Scovill established Victory Gardens in Wolcott during the spring of 1943. Eighty-two employees signed up for plots. Many other Waterbury companies also provided their employees with garden plots and offered advice on when to plan, plant, fertilize, and weed. Conservation and reclamation were high priorities: factory management developed ways to reclaim lubricating oil from processing of aluminum products, and new facilities were established for salvage departments to process waste materials and ship them to refineries.

Employees also were encouraged to contribute 10 percent of every paycheck to the purchase of war bonds under a special program set up by the Council of National Defense, first created in 1916 to coordinate the nation’s industry and other resources with the military. Celebrities came to Waterbury for the bond rallies. The Liberty House, a small structure used during the First World War, was renamed the Victory House and became a central stage for Bond Rallies on the Waterbury Green. Worker organizations participated in bond drive parades featuring veterans of World War I, factory guards, factory drum corps, and workers dressed as clowns and as Germans. In 1942, Scovill received a Treasury Department Certificate for having enrolled more than 90% of their employees in the payroll deduction plan.

top: Chase Metal Works foreman Louis L’Heureux atop a pile of used shell casings to be melted down and reused. “Chase News,” September 23, 1944. Bottom left: Ad in Scovill’s “The Bulletin,” December 7, 1942, for a fundraiser to buy cigarettes for overseas servicemen and hospitalized veterans. right: a display model of a time fuse, Waterbury Clock Company, 1942. Mattatuck Museum

Workers started the Scovill Employee Cigarette Fund in 1942 to raise money to purchase cigarettes for servicemen overseas and veterans hospitalized in the United States. They contributed to Community Chests and War Chests, which provided funds for 23 Waterbury services, the USO, and war relief agencies. Graphic images of foreign children injured or orphaned by the war were published in factory newsletters to spur further contributions to war relief funds.

Not All Smooth Sailing

Despite all of the propaganda aimed at raising morale and productivity, labor/management relations were frequently strained during the war, but unions remained dedicated to the meeting the needs of the military from going on strike. On May 2, 1944, however, 66 workers from the first shift at Scovill’s tube mill walked out in protest over numerous grievances. The union swiftly stepped in, telling second – and third – shift workers to stay at their posts while convincing those who had walked out to return the next. The dispute dragged out over several months. Scovill did not want to allow the strikers to return to their jobs but was required to take them back because of wartime needs.

In an effort to relieve some of the stress of war production, the companies promoted recreational activities. Scovill built a new recreation center in 1944 for the Scovill Employees Recreational Association (SERA), featuring a game room with billiard table, a lounge with reading lamps, fireplace, and radio, a kitchen, and a main hall designed for dancing and roller-skating. Employees participated in musical groups that included Freddie Bredice and his SERA-naders and the Scovill Male Chorus. Dances were held at Hamilton Park every weekend, with Frank Sinatra and Tommy Dorsey frequently coming up from New York City to play there on Sunday nights.

Company sporting teams competed regularly with annual tournaments between Chase and Scovill in pinochle and cribbage. Softball games were held between Scovill’s aluminum finishing and hot forge departments. In August 1943, the Waterbury Park Department announced expanding swimming pool hours at Chase Park to accommodate second- and third-shift workers.

Housing and Worker Shortages Appear

The demand for labor in Waterbury’s brass companies, as in industry across the nation, led to the recruitment of women into factory jobs they would normally not have considered or been considered for. Scovill began training women for factory work during the summer of 1942, noting “We are faced with the necessity of all-out production with a limited supply of skilled labor.” Women profiled in a September 28 Bulletin article included Anna Stanley, previously a bookkeeper and stenographer and now a tool grinder; Beryl Hutchinson, a seamstress now working a Universal Grinder; and Ethel Leopold, newly skilled in machine-tool work after leaving her job as a secretary. As the war continued, Chase in December 1944 launched an advertising campaign to recruit women. A Chase News article stressed that any woman taking a munitions job at Chase would “help bring this war to a successful end sooner.” The following summer, the life of Chase women workers was fictionalized in a 1945 romantic novel, Give Me the Starts, by Gladys Taber, who spent time in the case shop observing the details of operations.

The employment future for the women workers was unclear when the war finished. On August 27, 1945, Scovill’s The Bulletin profiled lathe operator Elanor Barkauskasr as an example of a woman worker who liked shop work “a great deal” but who said she would gladly give up her job to a returning serviceman or head of family. The Bulletin saluted her and all other women workers willing to give up their job.

Workers from all over the state and the region were drawn to Waterbury by the availability of jobs and by 1943, a housing shortage emerged. Three hundred housing units were quickly constructed on Long Hill, barracks were built in the South End, and larger homes were subdivided into small apartments throughout the city. Waterbury Tool’s Watco News reported in July that 100 rooms for single women war workers would be available on Long Hill by September or October. The Waterbury War Housing Center, a city department created to help war workers find housing, oversaw construction of housing and helped workers find rooms to rent throughout the city.

Still, the demand for workers depleted the locally available supply by early 1945, and in February 1945 close to 50 furloughed soldiers were assigned to take skilled and semi-skilled jobs at Scovill. They were given accommodations with various families throughout the city.

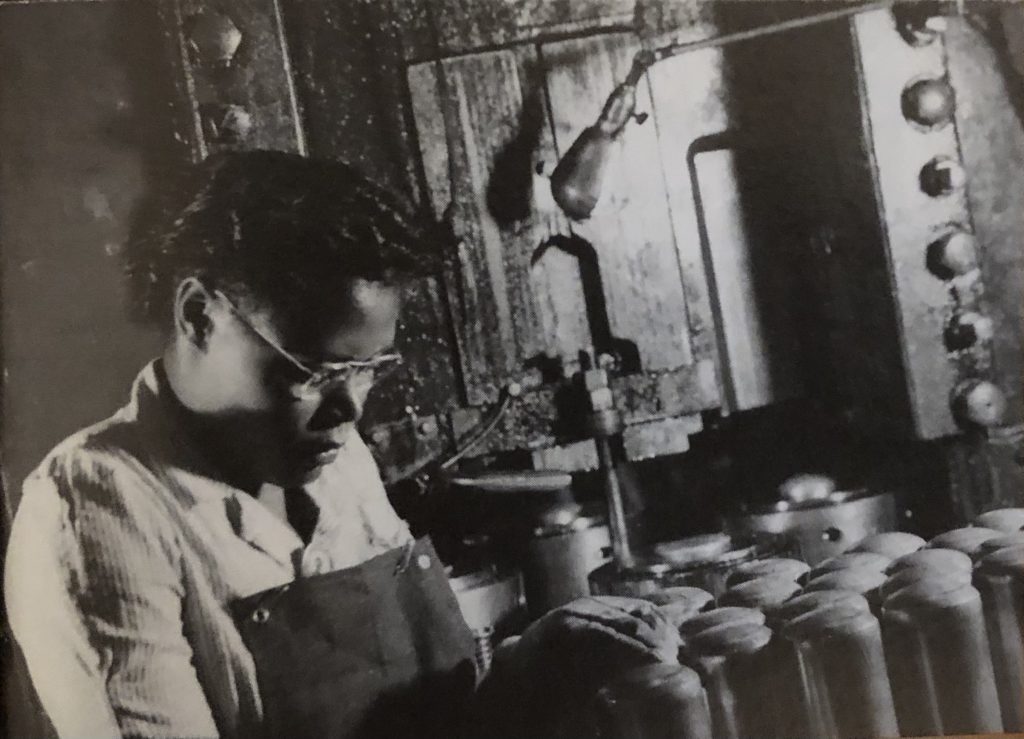

Evan Purcell and Gilbert Smith arrive at Scoville North Mill, 1945, two of the many Jamaicans brought to the U.S. to alleviate labor shortages. From Scovill’s “The Bulletin,” February 26, 1945. Mattatuck Museum

The War Manpower Commission recruited workers from Jamaica to help fill the void. In January 1945, 1,700 men who had signed up in Jamaica with the War Manpower Commission, arrived in New York. Chase Metal Works hired 171 of the workers, and smaller numbers were hired by Scovill and American Brass. Before arriving in Waterbury, the workers were subjected to a group interrogation by the FBI and Naval Intelligence and inspection by immigration and customs authorities. Most were assigned to the night staff at Chase, where they signed 90-day renewable contracts. Twenty-five percent of their pay was deposited by the factory into Jamaican banks, while another elven percent was deducted for income tax and Social Security. The workers were responsible for paying their room and board at the barracks and for transportation to a from the housing they were supplied in Plantsville and Meriden. At the end of the war, they were released from their contracts; most returned to Jamaica.

Celebrating Victory

As the war drew to an end, the factories began to focus on celebrations and the return to peace-time production. Planning for V-E Day began as early as September 1944, with company newsletters like the Chase News cautioning workers to contain their excitement until after they had followed normal routines for shutting down and clocking out. In November, Chase cautioned against allowing enthusiasm for the impending end of the war to slow down production.

When V-E Day arrived on May 7, 1945, Robert P. Patterson, the undersecretary of war, issued an urgent telegram to all factory workers, congratulating their efforts while reminding them that “The nation is counting on American labor and industry to provide the weapons and equipment needed to crush Japan.” Readers of Scovill’s The Bulletin were reminded of President Truman’s V-E Day speech in which he declared “work, work, and more work” as the key to bringing about V-J Day. The Watco News reported to that employees responded to the announcement of victory in Europe with “joy and with prayers of thanks” and without any “wild outbursts of emotion,” as they were all focused on the work ahead.

The restrained exuberance was unleashed on August 15, 1945. Victory over Japan was followed by a two-day state holiday. Factories were shut down. Workers left their plants in orderly fashion, then surged onto the streets for celebration. Waterbury’s downtown was packed with thousands of people cheering, singing, and dancing. Years of anxiety, hard work, and sacrifice had ended in victory.

Raechel Guest is an independent curator and teaches at The University of Connecticut in Waterbury. She is curator of Bombshells, Bond Rallies & Blackouts: Waterbury in World War II, a special exhibition at the Mattatuck Museum Arts & History Center this fall.

Explore!

Read more about Connecticut in World War II in our Fall 2020 issue commemorating the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II.

Read more stories about Connecticut at War on our TOPICS page.

Purchase our Collection of issues about Connecticut at War.