By Dawn C. Adiletta

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Feb/Mar/Apr 2004

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

“So far my health has been better than last summer,” wrote Harriet Beecher Stowe in July 1849. “I use all my hydropathy armor – cold bathing, wet bandages & sitz baths as I need them to keep my strength for emergencies…[M]y family has all kept uncommonly well so far…”[i]

By 1849, Stowe was a confident convert to hydropathy or the water cure. Her initiation, however, had occurred more than three years earlier. In 1846 Stowe was exhausted from rapidly consecutive pregnancies, overwhelmed with the demands of a meagerly funded household, and depressed over the death of her brother. She suffered a physical collapse. Funded by generous friends, Stowe spent nearly 11 months in Vermont at the recently opened Brattleboro Hydropathic Institution recovering her health. When she retreated to Brattleboro, Stowe, like many early-19th-century Americans, was questioning the efficacy of what they called “regular” medicine and seeking “irregular” alternatives to common medical practices of their day.

Prior to the Civil War, regular medicine, or allopathy, depended on relatively limited medical knowledge. In the centuries following Hippocrates’ initial attempts to establish medical standards, physicians had discovered a great deal about the human body, but by the 19th century, they were only beginning to understand the causes of many diseases or to recognize the difference between symptoms and the disease itself. Doctors disagreed about the reasons for illness or poor health, but their treatments were consistently based on the principles of heroic medicine.

THE HEROIC APPROACH TO TREATMENT

Heroic medicine advocated large or “heroic” doses of medication in order to produce humoral balance. The humoral theory of disease dates from the 5th century B.C. and remained fundamentally unchallenged up through the 18th century. Physicians believed that the human body contained four basic body fluids of “humors”: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. In a healthy person, the humors were balanced. Mild imbalances produced temperamental disorders. People could be phlegmatic, sanguineous, bilious, or melancholic. More severe imbalances in the humors, however, resulted in disease. Up until the middle of the 1700s, medical practitioners who sought to restore or create the humoral balance necessary to good health were guided by the principle of vis medicatrix naturae, or the belief in nature’s ability to health itself. Doctors believed that patients naturally eliminated excessive humors by spontaneously hemorrhaging, urinating and purging, and that doctors should assist nature only in extreme cases through selective bleeding with leeches, or by providing drugs or external plasters to encourage sweating, vomiting, or diarrhea.

This relatively noninvasive approach began to change in the mid-1700s, however, when doctors tried to create universal standards of medical treatment and play a larger role in combating disease. Promoted by leading physicians such as William Cullen of Edinburgh and Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia, and the humoral theory was augmented with attempts to control the patient’s “nervous energy.” According to Rush and his followers, if there was too much nervous energy, spasms could result. To reduce energy levels, bleeding, fasting, and purging were recommended. If there was too little nervous energy, the patient could become disabled. Stimulants, including large amounts of alcohol, a highly spiced diet, or irritating medications were the answer. Regular medicine also began to define pregnancy and childbirth as diseases that required medical intervention.

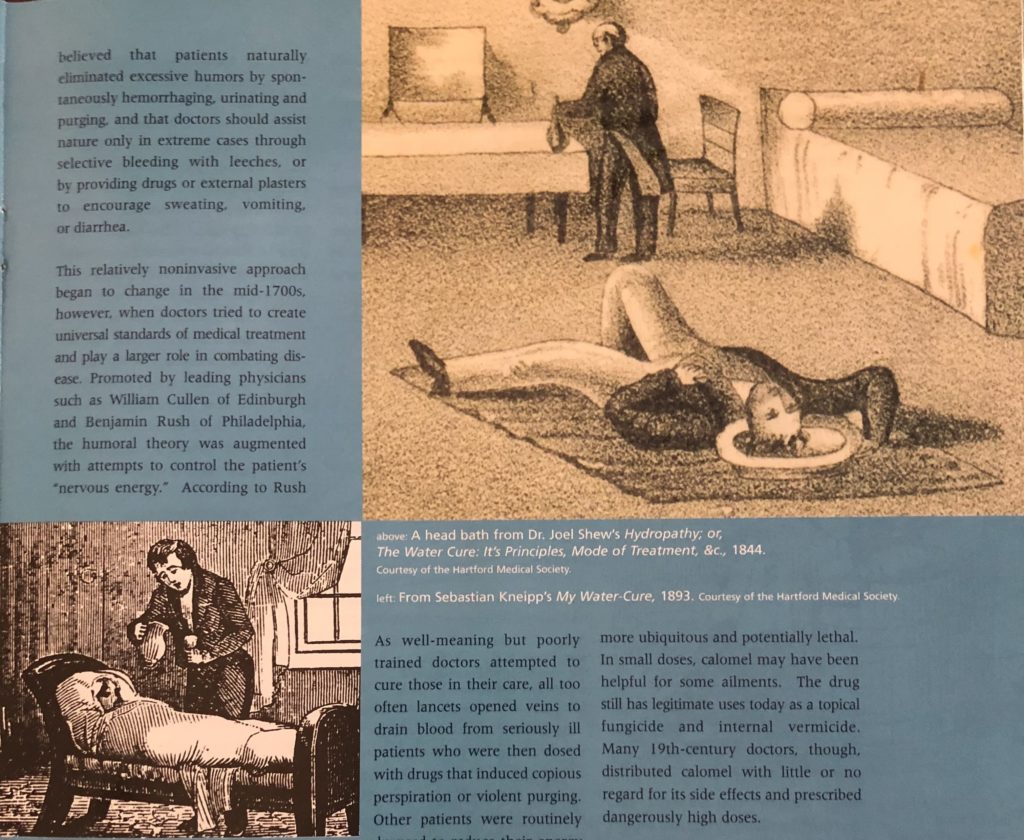

As well-meaning but poorly trained doctors attempted to cure those in their care, all too often lancets opened veins to drain blood from seriously ill patients who were then dosed with drugs that induced copious perspiration or violent purging. Other patients were routinely drugged to reduce their energy levels in the hopes of preventing disease from occurring.

By the early 1800s, the most commonly administered medications were opiates and the little blue pill called calomel, or mercurous chloride. Opiates were highly addictive, yet laudanum was proscribed for teething babies, temper tantrums and sleepless adults, and morphine freely dispensed for digestive disorders, broken bones, depression, and pregnancy. Calomel was even more ubiquitous and potentially lethal. In small doses, calomel may have been helpful for some ailments. The drug still has legitimate uses today as a topical fungicide and internal vermicide. Many 19th-century doctors, though, distributed calomel with little or no regard for its side effects and proscribed dangerously high doses.

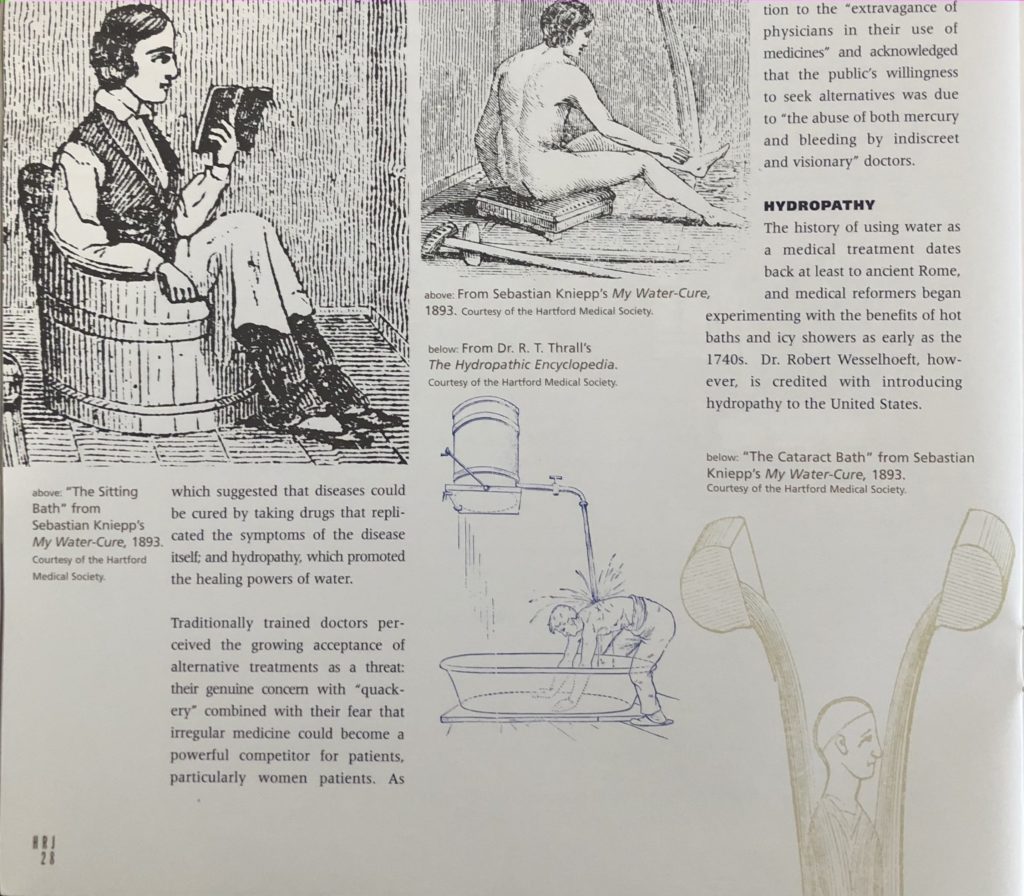

Writing to her brother, the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, Stowe described herself as “four or five times saturated” with calomel.[ii]As a wife and mother, Stowe was often the first medical resource for her children and husband, and, following the recommendations of regular doctors, she disguised the drug in her husband’s and children’s food in order to get them to take it routinely.[iii]Stowe and sister Catherine Beecher’s list of medical complaints strongly suggest that they suffered from overdoses of calomel. Their severe headaches, cognitive disorientation, nausea, tremors, and loss of muscle control in their hands are similar to the symptoms of mercury poisoning. As regular medicine not only failed to cure their problems but made them sicker, Stowe and her contemporaries began to look elsewhere for health care. Americans experimented with herbalism, called Thompsonian medicine; homeopathy, which suggested that diseases could be cured by taking drugs that replicated the symptoms of the disease itself; and hydropathy, which promoted the healing powers of water.

Traditionally trained doctors perceived the growing acceptance of alternative treatments as a threat: their genuine concern with “quackery” combined with their fear that irregular medicine could become a powerful competitor for patients, particularly women patients. As physicians tried to convince the public to place their trust solely in regular medicine, they blamed the clergy for encouraging alternative medicine. The doctors may have been right. Health reformers made a conscious effort to connect physical health with spiritual well being. Good health was natural, they argued, and the way God intended people to be. In order to make its services affordable to such influential clients, the Brattleboro Institute offered discounts to clergy of up to 75 percent.

Yet, even as the orthodox medical profession warned against quackery and “foolish clergymen,” some regular doctors recognized that there was good reason why irregular medicine attracted so many people. The August 1850 issue of New York Medical Gazette published one doctor’s speculation that “medical sects” were a reaction to the “extravagance of physicians in their use of medicines” and acknowledged that the public’s willingness to seek alternatives was due to “the abuse of both mercury and bleeding by indiscreet and visionary” doctors.

top right: A head bath from Dr. Joel Shew’s “Hydropathy; or, The Water Cure: It’s Principles, Mode of Treatment, &c.,” 1844. ; below left: From Sebastian Kneipp’s “My Water-Cure,” 1893. Courtesy of the Hartford Medical Society

HYDROPATHY

The history of using water as a medical treatment dates back at least to ancient Rome, and medical reformers began experimenting with the benefits of hot baths and icy showers as early as the 1740s. Dr. Robert Wesselhoeft, however, is credited with introducing hydropathy to the United States.

Wesselhoeft had studied the water cure under the famed hydropath Vincent Priessnetz of Grafenberg, Austria. Priessnetz claimed he had healed his own broken ribs and crushed hand by soaking in cold spring water. By 1839, he was one of the leading European proponents of hydropathy, with more than 2,000 patients. When Priessnetz cured Robert Wesselhoeft of rheumatic fever in 1840, he created a powerful advocate for this irregular medical practice. Hoping to create a spa as successful as Priessnetz’s, Wesselhoeft immigrated to the United States. By 1841, he was the proprietor of a thriving water-cure practice in West Roxbury, Massachusetts that attracted members of the Boston social and literary elite including Margaret Fuller, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

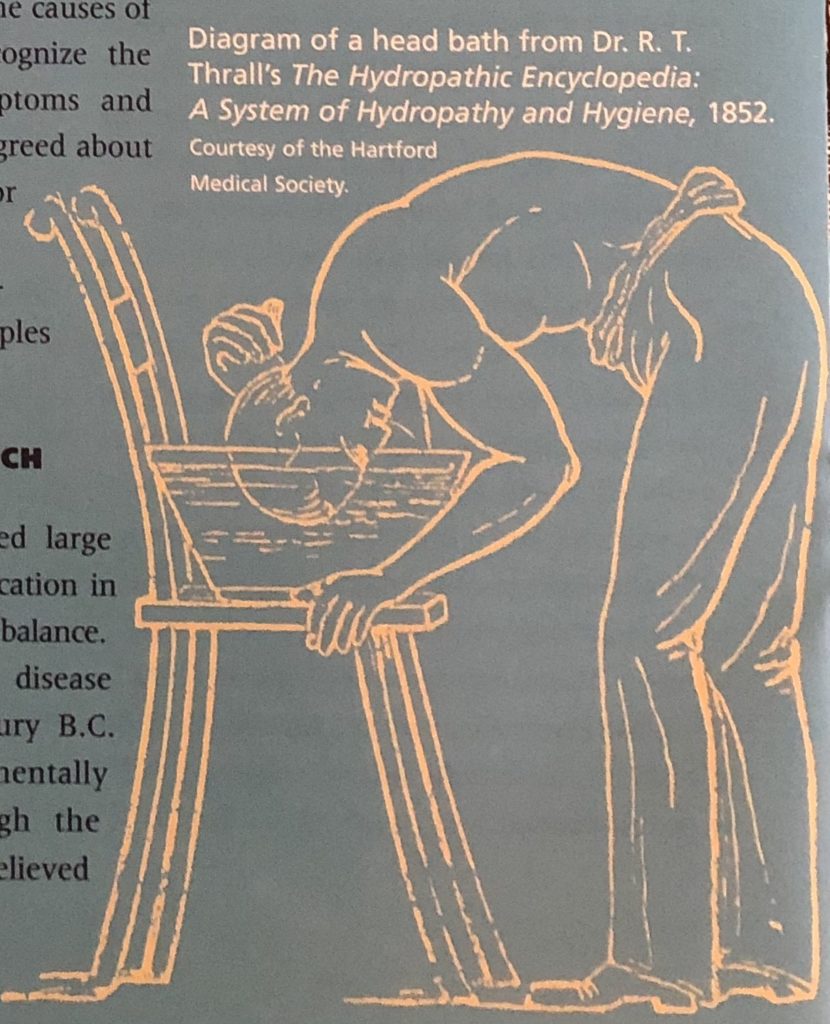

At the heart of hydropathic treatment was, of course, water. Patients took long baths, either completely immersing themselves or soaking specific portions of their bodies. Arm baths treated neuralgia, chronically cold hands, sore throats, or a bad cold. Head and neck baths relieved tension in the upper back, migraines, mild depression, or vertigo. Sleeplessness and cold feet were treated with cold foot baths. Sitz baths remedied bladder and bowel complaints. Long soaks in warm water were recommended for overly excited patients. Patients who need to be invigorated – like Harriet Beecher Stowe – stood beneath powerful showers called douches, of cold water falling from as much as 20 feet. “Packings,” or being wrapped in wet bandages or sheets and then covered with blankets, were common. And of course, patients drank and drank and drank. Some establishments recommended up to 30 glasses of water a day.

Philosophically opposed to allopathic medicine’s reliance on heroic treatment, hydropathy offered a gentler if sometimes still uncomfortable means of removing toxins from the patient’s body. The showers, baths, and sweatings were intended to open the patients’ pores, while water consumption and packings were supposed to provide a supply of pure water to replenish the system.

Hydropathic institutions combined water treatments with regular vigorous exercise, low-fat high-fiber diets, and a stress-free environment. Stowe reported walking five to seven miles a day soon after her arrival in Brattleboro. She attributed newly recovered ability to do so to the invigorating cold showers she took.

THE BRATTLEBORO HYDROPATHIC INSTITUTION

Regular doctors in general were not pleased with Wesselhoeft’s growing popularity. In a sweeping condemnation, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes (father of the Supreme Court justice) called homeopathy a “pretended science” and characterized Wesselhoeft as one of many “empirics, ignorant barbers, and men of that sort… who announce themselves ready to relinquish all the accumulated treasure of our art, to trifle with life upon the strength of these fantastic theories.”[iv]Holmes’s social position made him a powerful critic, and Wesselhoeft decided to leave the Boston area. After one of Wesselhoeft’s patients told him of the springs near Brattleboro, Vermont, Wesselhoeft relocated to the Connecticut River Valley, and in 1845, with the help of his brother Richard, a practitioner with traditional medical training, opened one of the most exclusive water-cure establishments in the United States. When Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe became clients in 1846, they were among the earliest to accept and promote this popular medical reform.

Illustrations of water cures from Sebastian Kniepp’s My Water-Cure, 1893 and Dr. R. T. Thrall’s The Hydropathic Encyclopedia. Courtesy of the Hartford Medical Society

Despite the fact that many of the precepts of hydropathy could be applied at home, a water cure was not for those on limited budgets. The Brattleboro Hydropathic Institution was one of the most expensive water-cure establishments in the United States with costs ranging from $5 to $10 per week, a significant amount of money at a time when homes could be rented for $600 a year. Water-cure establishments marketed themselves to well-educated affluent women and men. Brattleboro’s patients included leading politicians, well-known literary figures, and social reformers. The costs would have been prohibitive for the perennially broke Stowe family if admirers had not gathered the funds for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s treatment. Husband Calvin benefited from the discounted ministerial rate.

Catherine Beecher’s experience was typical. Her day began at “four in the morning packed in a wet sheet…” A few hours later, she was “immersed in the coldest plunge-bath.” After dressing, she took long walks which were followed by “five or six tumbles of coldest water.”[v]Then came breakfast. Late morning brought 10 long minutes of standing beneath icy water falling from 18 feet. The day continued with more baths and walks, multiple glasses of water, until she was finally wrapped in wet bandages and put to bed at 9:30. Such treatments were carried on year round. As Stowe stayed on through the summer and fall of 1846 and into the winter of 1847, she described the increasingly cold conditions. Ice built up in the showers, yet Stowe and other hearty believers took multiple icy “scrubbings” and hiked up to 10 miles a day.[vi]

Meals were often based on the recommendations popularized by former clergyman Sylvester Graham. Strict Grahamites avoided all animal products and ate fruits, vegetables, and breads and crackers made from the hole bran flour that came to bear his name. Graham’s followers also prohibited the use of tobacco, alcohol, coffee, and tea and severely curtailed sexual relations.

Most hydropathic establishments avoided allopathic cures entirely, but under the direction of Robert Wesselhoeft’s brother, Richard, the Brattleboro Institution took a more moderate course. Dr. Richard Wesselhoeft permitted the use of small doses of regular medicines, but banned tobacco and alcohol. Prohibiting alcohol was a response to temperance reforms already affecting American society, but the ban also spared water-cure clients from the alcohol-based “stimulating” medications regular doctors prescribed. One of the chief benefits of the water cure was that they helped patients flush their systems of the opiates and other toxins prescribed by regular doctors.

From the beginning hydropathy was closely connected to other 19th-century reforms, with particular implications for women. Responding to the newly forming women’s rights movement, supporters of hydropathy advocated dress reform, and argued that a woman’s health was her “first great right.” Water-cure establishments promoted themselves as retreats where women could leave “false, expensive, extravagant, foolish [and]fashionable life” and become “free to get well.”[vii]Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Clara Barton, and Susan B. Anthony were among the many notable women reformers who underwent hydropathic cures.

WATER CURE IN THE ERA OF REFORM

Water-cure enthusiasts called the experience a “radical reform in the healing art.”[viii]Many hydropathic centers hired women doctors, and promoted their “Ladies Departments.” Mary Louise Shew, who with her husband and business partner Joe Shew ran a water cure in New York, advocated hydropathy for women in her book, The Water Cure for Ladies. Shew warned her readers against the “so-called science of medicine” and urged women to “learn and think for themselves.”

Hydropaths encouraged women to be involved in their own medical treatment and gave them tools to deal with common medical childhood complaints, such as teething, weaning, colds, and fevers. They regarded pregnancy and childbirth as natural, just as midwives had, before regular doctors in the late 18th and early 19th centuries diagnosed them as diseases that required blood letting, caustic drugs, and enforced bed rest for weeks after delivery. Stowe became a firm believer in hydropathy. She credited the system for the healthy pregnancy and easy delivery of her sixth child, Charlie, and used hydropathic techniques to treat her children. When they were stricken with cholera, she applied cool, damp cloths to help break their fevers instead of dosing them with the recommended calomel. Sprained ankles and bruised arms were confidently wrapped in wet bandages.[ix] More than a decade after her stay in Brattleboro, Stowe wrote to a friend that she would “…trust to find you a fair sample of the wonder working powers of the waters.”[x]

Water-cure establishments welcomed both men and women, but male and female clients stayed in separate facilities, even if they were married. In Brattleboro, Stowe lived in a dormitory-like environment called Paradise Row where she shared “long, long talks” with other women. When husband Calvin Stowe arrived in Brattleboro during the summer of 1846, they occupied separate quarters, much to Calvin’s disappointment. He enjoyed his weeklong treatment except for the “mean business of sleeping in another bed, another room, and even another house….”[xi]

But the “mean business of sleeping in another bed” may have been a major attraction for many women clients. With limited awareness or use of contraception, planned parenthood, or “voluntary motherhood,” was achieved through abstinence; something that was easier to practice if partners were separated. Women physically depleted from frequent pregnancies and the often harmfully intrusive treatments from regular doctors benefitted from a retreat to a water-cure establishment where rest, regular exercise, a healthy diet and a respite from child care and possible pregnancy restored their health.

Diagram of a head bath fro Dr. R. T. Thrall’s “the Hydropathic Encyclopedia: A System of Hydropathy and Hygiene, 1852. Courtesy of the Hartford Medical Society

Interest in hydropathy peaked around 1860, although water-cure establishments remained popular throughout the 19thcentury. After the Civil War, many hydropathic establishments improved their accommodations and added more social activities in order to attract a new audience. Diets became less strict, and musical entertainment filled many evenings. Many former water-cure centers, like Saratoga Springs, were soon more associated with horse racing and matchmaking than health. Institutions that wanted to maintain their focus on health shifted to the gentler field of hydropathy, which replaced icy deluges with tepid soaks and hot springs. In the last quarter of the 19th century, diet reformers Charles W. Post and brothers W.K. and J.H. Kellogg opened their own retreats in Battle Creek, Michigan. Although the Kelloggs and Post emphasized the importance of a high fiber diet, hydrotherapy was also an essential element of their establishments.

Robert Wesselhoeft who had brought hydrotherapy to the United States became seriously ill in 1851 and returned to Germany for treatments. He died there in 1852. The Brattleboro Hydropathic Institution continued to treat people for another two decades before finally closing its doors in 1871.

Catherine Beecher remained a believer in hydropathy and spent time at treatment centers in Northampton, Massachusetts and Elmira, New York. She spent her final years with her brother Thomas and his wife near the Elmira Water Cure Facility so she could continue to take treatments. Harriet Beecher Stowe donned “all her hydropathy armor” for some time. Her belief in the curative and preventative powers of hydropathy, however, could not protect her family from cholera. Only weeks after she confidently wrote to sister-in-law Sarah Beecher, three of her children were stricken, and 18 month old Charlie was dead. The crushing loss helped inspire Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but it did not shake her faith in the water cure. As time passed, however, she modified her approach to health care.

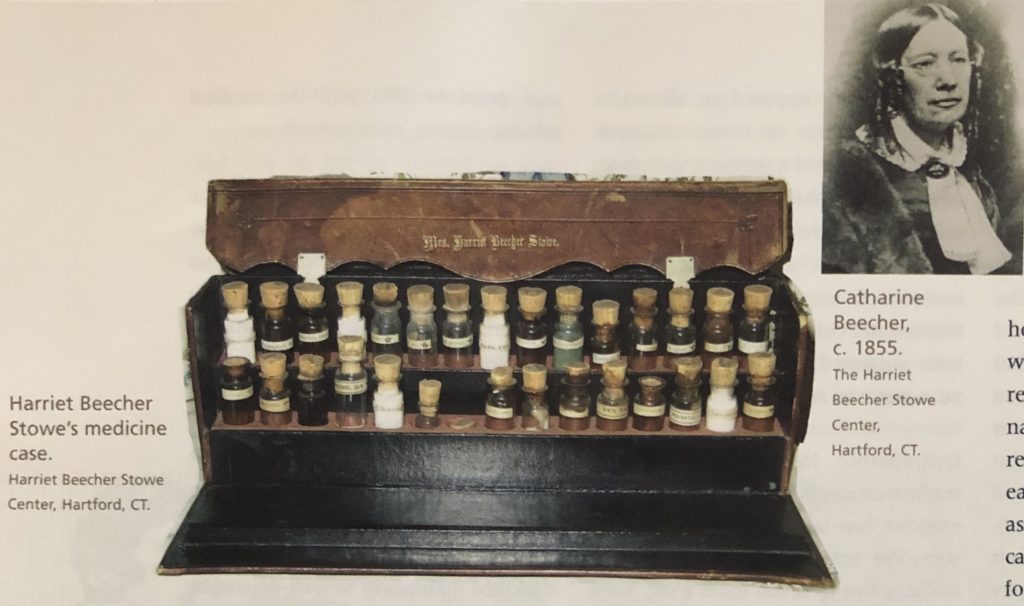

She drank wine with dinner “for her health,” and her pharmaceutical receipts document her willingness to give quinine to Calvin to fight his malaria attacks. Although quinine is derived from herbal sources it had been recommended by orthodox physicians since the 1700s. While living on Forest Street in Hartford, Stowe purchased a Moroccan leather travelling medicine case now on display at the Harriet Beecher Stowe House. The case contained traditional herbal and homeopathic, as well as allopathic, remedies. Just as Stowe’s trip to Brattleboro reflected society’s popular acceptance of alternative medicines, her later willingness to combine various medical philosophies was increasingly typical of many late 19th-century patients and doctors. It was also typical of Stowe’s own desire to locate the truth wherever it lay.

Dawn C. Adiletta was curator of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center at the time she researched and wrote this story. She wrote about the Katherine Seymour Day House in the Summer 2003 issue.

EXPLORE!

“Stafford Springs: President John Adams Takes the Water Cure,” Spring 2007

Find more stories about Harrier Beecher Stowe and the Beecher family on our Notable Connecticans TOPICS page.

Read more stories about Health & Medicine in Connecticut history on our TOPICS page.

Subscribe to receive every issue!

NOTES

[i]Harriet Beecher Stowe to Sarah B. Beecher, July 10, 1849, Acquisitions Harriet Beecher Stowe Center Library[ii]Harriet Beecher Stowe to Henry Ward Beecher, nd. cited in Joad D. Hendrick, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994) p. 174. Stow probably meant that she was taking heavy doses on a daily basis. However, “saturated mercury” was another name for calomel and she may have been making a pun. The Beechers were very fond of puns.

[iii]Ibid.

[iv]Oliver Wendell Holmes, Lectures on Homeopathy and Its Kindred Delusion, (Boston: Boston Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, 1842)

[v]Catherine Beecher, Letters to the People on Health and Happiness, (New York: Harper & Bros., 1855) p. 117.

[vi]Harriet Beecher Stowe to Eunice and Henry Ward Beecher, January 14, 1847, Beecher Family Papers, Sterling Memorial Library cited from Hendrick, p. 183.

[vii]Water Cure Journal, December 20, 1855, p. 135.

[viii]Water Cure Journal, June 1, 1849, p. 185.

[ix]Harriet Beecher Stowe to Rebecca Wetherill, July 21, 1860. Katherine Seymour Day Collections. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center Library

[x]Harriet Beecher Stowe to Rebecca Wetherill, September 16, 1860. Katherine Seymour Day Collections. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center Library

[xi]Calvin E. Stowe to Harriet Becher Stowe, August 20, 1846. Acquisitions. Harriet Beecher Stowe Library.