By Gregg Mangan

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In an era before the Internet, television, or even live radio broadcasts, fans of professional baseball watched re-creations of games around the country thanks to the Baseball Playograph Company in Stamford, Connecticut. That company brought live baseball to tens of thousands of Americans through the production of its “playograph” product.

Playographs resembled large billboards, often standing about nine feet high. Making up either side of the playograph was a vertical listing of the player lineups for each team. In the middle of the playograph was a reproduction of a baseball diamond, along with places for playograph operators to indicate balls, strikes, outs, and runs in real time.

The ingenious invention was operated by two men hidden from public view. The operators received transmissions from telegraph operators who watched the games live and communicated details about every play. Upon receiving each update, playograph operators depicted the transmissions on the playograph by manually moving a baseball attached to strings or wires around the baseball diamond.

The ball sat still on the pitcher’s mound until operators received information about the game’s next pitch. The operator then moved the ball toward home plate in a fashion that replicated the pitch thrown. Playograph viewers saw the ball move directly and deliberately toward home plate for fastballs; for curveballs, it moved with a sudden swing left or right at the end. If a batter made contact, the playograph operator moved the ball to a spot on the diamond reproduction that corresponded to where it had been hit in the game. A small “fly ball” indicator let viewers differentiate between balls hit on the ground and those hit into the air, while an “X” on a base represented a runner and an “O” indicated a runner who was out.

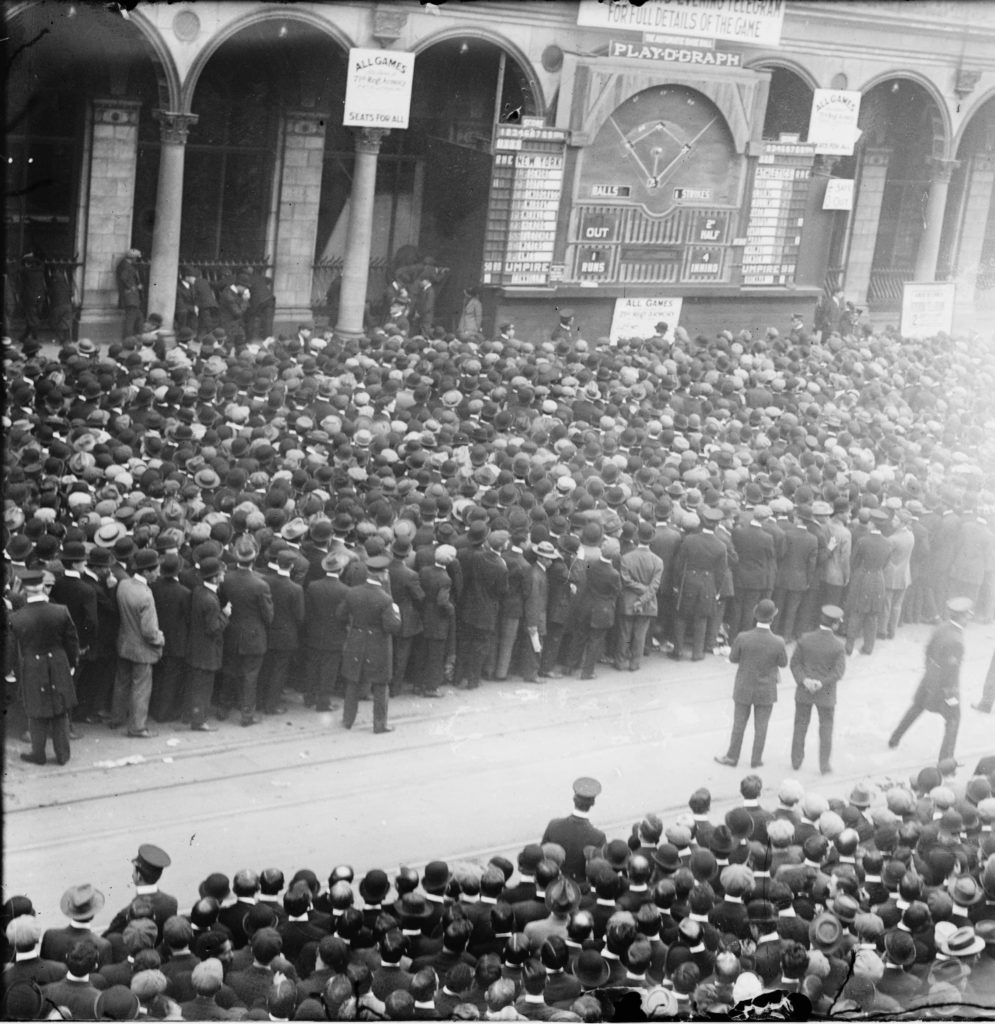

Playographs appeared on the sides of buildings and inside theaters and opera houses and were wildly popular from the 1890s until the early 1930s. Playographs were used primarily for important games, such as those of the World Series. One example was the 1911 World Series games between the New York Giants and the Philadelphia Athletics. New York’s Evening Telegram estimated that 70,000 people watched the first game (October 15, 1911) of the 1911 series on their Baseball Playograph Company’s playograph in Herald Square—nearly double the 38,000 who watched the game live at the Polo Grounds in New York (if their estimate can be trusted). Their coverage captured the excitement:

Thousands watched the 1911 World Series between the New York Giants and the Philadelphia Athletics recreated in real time on Stamford’s Baseball Playograph Company’s playograph in Herald Square, New York. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

With tense interest that strained all eyes towards the quivering ball in the center of the miniature diamond the crowd caught each ball, each strike and each “out” of the final inning and in the fraction of a second changed from breathless silence into a cheering, shouting, hat-waving, back-slapping throng which swept up and down Broadway with a roar of victory.

The Baseball Playograph was just one of many competing products to bring baseball action to fans across the country in real time as early as the 1880s; some incorporated electricity and lights as early as 1891, according to blogger and amateur historian Mark Schuban, writing on his Web site Schubincafe.com. While playographs helped spread the popularity of baseball and bring together an entire community of sports enthusiasts, public outdoor displays in downtown areas proved a nuisance to local business owners, who found access to their establishments limited or completely blocked by the throngs of fans gathering around. Playograph use waned when radio stations began broadcasting baseball games in the 1920s and games began to be televised in 1939.

Gregg Mangan is an author and historian who holds a PhD in public history from Arizona State University. This story originally appeared on Connecticuthistory.org.

Explore!

Read all of our Sports history stories on our TOPICS page.