by Elizabeth Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

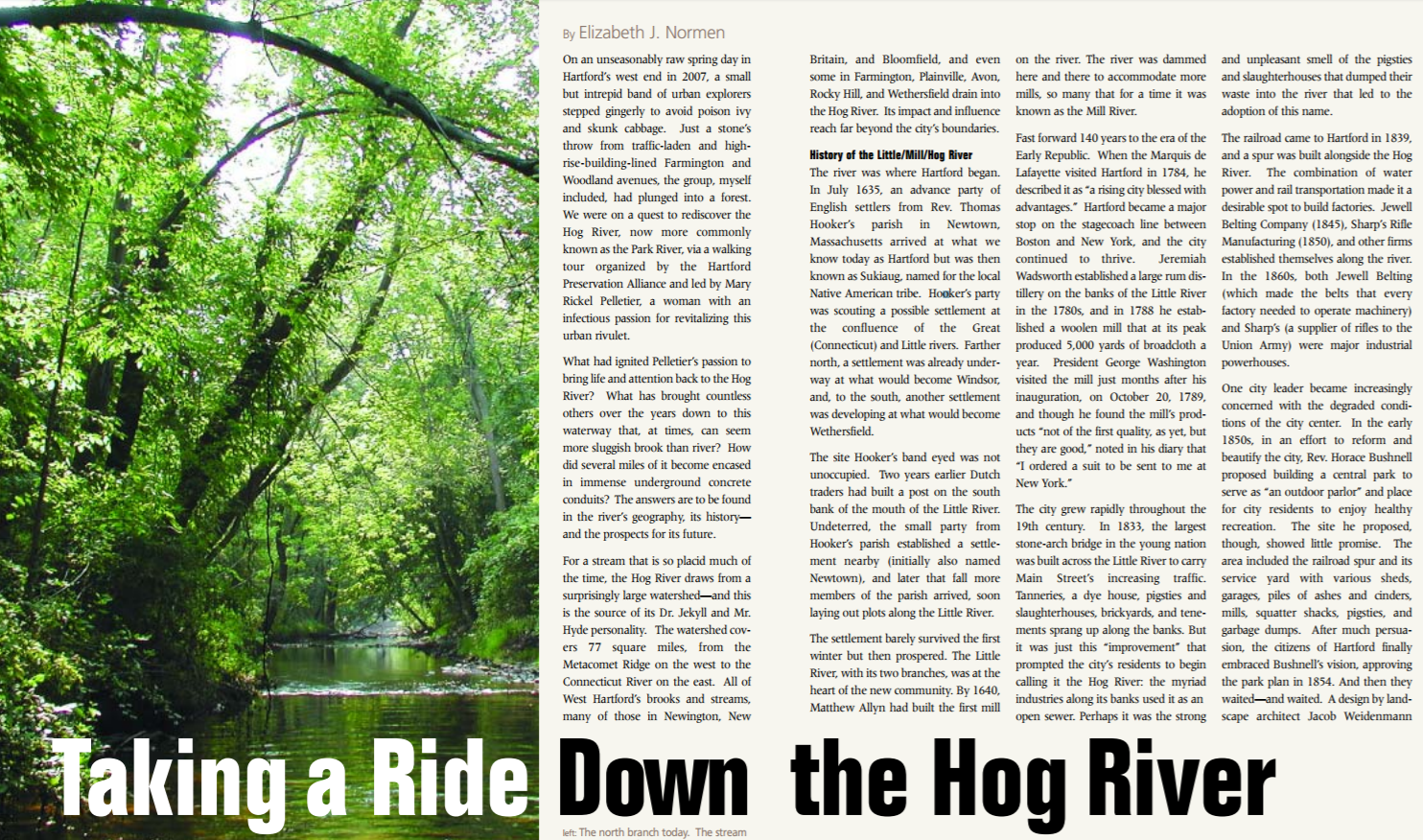

On an unseasonably raw spring day in Hartford’s west end in 2007, a small but intrepid band of urban explorers stepped gingerly to avoid poison ivy and skunk cabbage. Just a stone’s throw from traffic-laden and highrise-building-lined Farmington and Woodland avenues, the group, myself included, had plunged into a forest. We were on a quest to rediscover the Hog River, now more commonly known as the Park River, via a walking tour organized by the Hartford Preservation Alliance and led by Mary Rickel Pelletier, a woman with an infectious passion for revitalizing this urban rivulet.

What had ignited Pelletier’s passion to bring life and attention back to the Hog River? What has brought countless others over the years down to this waterway that, at times, can seem more sluggish brook than river? How did several miles of it become encased in immense underground concrete conduits? The answers are to be found in the river’s geography, its history— and the prospects for its future.

For a stream that is so placid much of the time, the Hog River draws from a surprisingly large watershed—and this is the source of its Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde personality. The watershed covers 77 square miles, from the Metacomet Ridge on the west to the Connecticut River on the east. All of West Hartford’s brooks and streams, many of those in Newington, New Britain, and Bloomfield, and even some in Farmington, Plainville, Avon, Rocky Hill, and Wethersfield drain into the Hog River. Its impact and influence reach far beyond the city’s boundaries.

History of the Little/Mill/Hog River

The river was where Hartford began. In July 1635, an advance party of English settlers from Rev. Thomas Hooker’s parish in Newtown, Massachusetts arrived at what we know today as Hartford. Hooker’s party was scouting a possible settlement at the confluence of the Great (Connecticut) and Little rivers. Farther north, a settlement was already underway at what would become Windsor, and, to the south, another settlement was developing at what would become Wethersfield.

The site Hooker’s band eyed was not unoccupied. It was a village of the local Wangunk called Sukiog. Two years earlier Dutch traders had built a post on the south bank of the mouth of the Little River. Undeterred, the small party from Hooker’s parish established a settlement nearby (initially also named Newtown), and later that fall more members of the parish arrived, soon laying out plots along the Little River.

The settlement barely survived the first winter but then prospered. The Little River, with its two branches, was at the heart of the new community. By 1640, Matthew Allyn had built the first mill on the river. The river was dammed here and there to accommodate more mills, so many that for a time it was known as the Mill River.

Fast forward 140 years to the era of the Early Republic. When the Marquis de Lafayette visited Hartford in 1784, he described it as “a rising city blessed with advantages.” Hartford became a major stop on the stagecoach line between Boston and New York, and the city continued to thrive. Jeremiah Wadsworth established a large rum distillery on the banks of the Little River in the 1780s, and in 1788 he established a woolen mill that at its peak produced 5,000 yards of broadcloth a year. President George Washington visited the mill just months after his inauguration, on October 20, 1789, and though he found the mill’s products “not of the first quality, as yet, but they are good,” noted in his diary that “I ordered a suit to be sent to me at New York.”

The city grew rapidly throughout the 19th century. In 1833, the largest stone-arch bridge in the young nation was built across the Little River to carry Main Street’s increasing traffic. Tanneries, a dye house, pigsties and slaughterhouses, brickyards, and tenements sprang up along the banks. But it was just this “improvement” that prompted the city’s residents to begin calling it the Hog River: the myriad industries along its banks used it as an open sewer. Perhaps it was the strong and unpleasant smell of the pigsties and slaughterhouses that dumped their waste into the river that led to the adoption of this name.

The railroad came to Hartford in 1839, and a spur was built alongside the Hog River. The combination of water power and rail transportation made it a desirable spot to build factories. Jewell Belting Company (1845), Sharp’s Rifle Manufacturing (1850), and other firms established themselves along the river. In the 1860s, both Jewell Belting (which made the belts that every factory needed to operate machinery) and Sharp’s (a supplier of rifles to the Union Army) were major industrial powerhouses.

One city leader became increasingly concerned with the degraded conditions of the city center. In the early 1850s, in an effort to reform and beautify the city, Rev. Horace Bushnell proposed building a central park to serve as “an outdoor parlor” and place for city residents to enjoy healthy recreation. The site he proposed, though, showed little promise. The area included the railroad spur and its service yard with various sheds, garages, piles of ashes and cinders, mills, squatter shacks, pigsties, and garbage dumps. After much persuasion, the citizens of Hartford finally embraced Bushnell’s vision, approving the park plan in 1854. And then they waited—and waited. A design by landscape architect Jacob Weidenmann was finalized in 1861, and Bushnell Park opened to the public in 1865. The river’s name was beautified, too: it became the Park River.

Meanwhile, the city continued to grow, and as it did so, it annexed more land to the north, south, and west. In 1859, the north and south branches of the (now) Park River were designated the city’s western boundary. In the 1860s and 1870s (respectively), Harriet Beecher Stowe and Mark Twain moved into Hartford’s Nook Farm neighborhood nestled into a picturesque crook in the north branch at the city’s western edge. Twain’s house, built in 1874, overlooked the river.

By the 1880s, the problem of the river’s pungent smell caused by human and animal sewage and industrial waste had become acute and a frequent topic of debate in The Hartford Courant. Sewage was draining into the river from as far away as New Britain. The river was described as “a stream hopelessly foul and sluggish.” Dead cats and fish were frequently seen floating on its surface. Though the extent to which the river posed a public health hazard was still not fully understood, in July 1880 the city formed a joint committee on “the Park River Nuisance.” All solutions— either to prevent waste from being dumped into the water in the first place or to flush the offending waste into the Connecticut River more expeditiously by pumping water into the Park River when its level was low—were beyond the city’s means, and city residents continued to suffer with the nuisance in their midst.

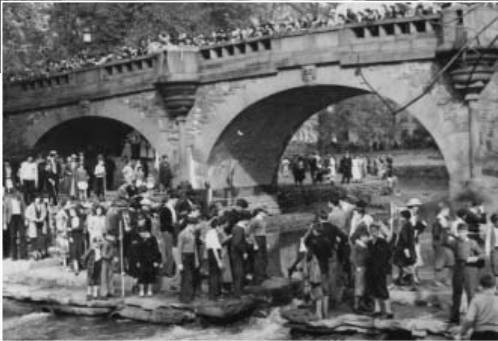

Times of heavy rain and snow melt invariably brought flooding, particularly when a rising Connecticut River backfilled the Park River. The record flood levels and major damage wrought by the Flood of 1936 and the Hurricane of 1938 finally brought this issue to a head, and the city could finally look forward to relief. Mayor Thomas J. Spellacy established a Flood Control Commission in 1936. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt visited Hartford on October 23, 1936. Addressing 50,000 people in Bushnell Park, he promised federal aid for flood control.

The will and the resources to solve the flooding problem finally came together. Hartford’s rapidly expanding defense industry needed protection in the event that the U.S. entered World War II. The Hartford Department of Engineers and the U.S. War Department developed plans for dikes to protect the city from the Connecticut River as well as for twin concrete conduits 30 feet wide and 19 feet high to control the Park River—by burying it underground. Burial of the Park River began in September 1940 and was completed three years later [see “A River Runs Under It: A Hog River History,” Hog River Journal, Fall 2002, or online at www.hogriver.org].

Waiting for President Franklin D. Roosevelt to speak in Bushnell Park, October 23, 1936. Roosevelt would promise federal aid for flood control. Hartford Public Library

The first phase of the conduit was just over a mile long and ended between the Capitol and Armory buildings. As a result of the Flood of 1955 and the construction of Hartford High School, the section from the Armory around the Twain House to Farmington Avenue was buried in the early 1960s. Additional sections of the south branch were put underground or in culverts with the building of I-84 in the late 1960s.

Tales of the Hog River

Despite the Hog River’s unsavory history and continuing unsanitary conditions, for many who grew up in Hartford in the 20th century the river was a year-round playground. In the summer it offered an option (if not an oasis) for swimming; in the winter it offered ice skating. Willis Wilbur of California, who grew up near the north branch in the 1920s and ‘30s, tells how as a boy he spent

many a summer day fishing and swimming in the Hog River…. I caught pickerel, which were fun to catch and good to eat. Generally the water was clear but occasionally it was discolored by the practice of cleaning the pig pens into the stream. However nobody complained about the clarity or the potability of the water and no one got sick. The older boys would sometimes chase us out of our favorite swimming hole and we would sneak back and tie up their clothes in knots…. Sometimes one of us would get caught and would be punished—that is how I learned how to swim.”

Ray Czapkowski, on the other hand, grew up near the more industrialized south branch, which offered fewer recreational opportunities because of the industrial pollution poured into it by factories along Capitol Avenue. Czapkowski remembered,

As youngsters we used to play in the Pope Park stretch between Capitol Avenue and Park Street. The Hog River was fairly polluted then and always had an oily film. We avoided getting too close to the banks for fear of slipping in. No one in their right mind would voluntarily go in the river. I recall this so well because it cost me a fortune one summer. A bully from Riverside (the Underwood [typewriter factory]side of the river) taunted me to go in, offering me $1.00 if I swam across. I refused and challenged him to do it. He did and was covered in an ugly, oily slime when he emerged. That dollar was a month’s allowance for me!”

Mary Kilgour opens her memoir, Me May Mary (Child Welfare League of America, Inc., 2005) with a shocking story of betrayal on the Hog River in the 1950s. On a hot June day when she was 11, she and a 10-year-old friend went down to the river to meet friends, cool off, and play on a raft they’d found. But the two girls found only one boy they knew from school and a group of strange boys “from the orphanage.” Events turned ugly when several of the boys held her while another pulled down her bathing suit. Her screams and physical resistance fortunately deterred further assault. She writes:

Oh come on, leave her alone. She doesn’t want it,” said not Jimmy, but a boy I didn’t know who was in the water by the raft. “Yeah, The hell with it.” The one holding my right leg let it go and made a running jump into the water. He started to drift downstream with the current. For a moment nothing else happened. I could hear the cars on the avenue, the splash of water. …The other boys let go.”

Riding Down the Hog River

The walk in June 2007 was my second close-up and personal experience with the Hog River. Two years earlier, when John Kulick of Huck Finn Adventures in Canton invited the HRJ staff to take a canoe trip down the Park River conduit in August 2005, I jumped at the chance. Kulick had been offering such trips to the public off and on for several years, but the City of Hartford had halted the tours over liability concerns. In an effort to change the city’s mind, Kulick was inviting city counselors and members of the press to experience the tour.

Canoeing inside the Park River (formerly the Hog River) conduit, August 2003, (l) Nancy Albert, (r) Elizabeth Normen. photo: Connecticut Explored

Entering the pitch-black conduit of the south branch adjacent to Pope Park felt like the beginning of a fun house ride at an amusement park. We were outfitted in life jackets, headlamps, and glowstick necklaces. Only our headlamps illuminated the concrete walls and the reflective surfaces of flotsam: a shiny bicycle reflector, a metal grocery cart, and a couple of lost basketballs. Fortunately no native, urban “fauna” scurried by. When we were approximately underneath Hartford Public Library, we headed down a slight incline, picking up speed on mini-rapids. Further on, the air became so humid and thick that even my headlamp could not illuminate past the bow of my canoe. Kulick had us turn off our headlamps and briefly float in the absolute darkness and quiet. About two and a half hours into the trip and now having to put some effort into paddling against the surge of the Connecticut River, we saw the light at the end of the tunnel. Our small flotilla emerged into the bright sunshine; we paddled past city kids fishing, and pulled out at scenic Charter Oak Landing.

The River’s Future

Though rides down the conduit remain off limits, the city is not unconcerned about the river and the role it might play in the city’s future. In 1999 it commissioned an assessment whose findings touted the Park River as a major environmental asset. The Park River Project Environmental Review Team Report (2000) conducted by the Eastern Connecticut Resource Conservation and Development Area, Inc. (ECRCDA) surveyed the length of the river’s two branches, assessing the water quality and condition of the adjacent habitat, and made recommendations for how the city might both better care for the river and find ways to reconnect people to this natural resource.

The report found water quality was still compromised—no longer by industrial dumping but by storm run-off that included combined sewage overflow. The Metropolitan District Commission is working to address this problem as part of an $800-million project to separate storm drains from sewers in Greater Hartford.

Despite the less-than-perfect water quality, the investigators spotted numerous great blue herons, a green heron perched on a shopping cart in the south branch, and mallard and wood ducks. They found evidence of deer, coyote, and fox. A 1988 fish survey noted pickerel, abundant blacknosed dace, large-mouth bass, and a handful of other varieties of fish.

Improving the water quality is a current goal, and monitoring is ongoing. The Park River Assessment Program is an EPA-funded project that began in October 2007. The Children’s Museum, the Farmington River Watershed Association, and the Park River Watershed Revitalization Initiative are working together, recruiting family teams and community youth groups to adopt a stream in the watershed and monitor the water quality and habitat along its banks. The state is concerned with water quality, too, and is developing a watershed management plan specifically for the north branch and its tributaries.

The ECRCDA received a $500,000 grant from the state Department of Environmental Protection to develop a greenway along the south branch of the river in the southwestern section of Hartford. A number of organizations, including the Knox Parks Foundation, the City of Hartford, and the Behind the Rocks/Southwest neighborhood group have been working together to develop the trail. Construction of the first phase was set to begin this spring.

In 2004, The Hartford Courant proposed that, like Providence, Hartford “daylight,” or uncover, its little river, specifically the portion from Hartford Public Library east to the Connecticut River. This section (currently buried under the Whitehead Highway) would be adjacent to the proposed Front Street development and could provide a very attractive amenity to this redeveloping section of the city. The consensus at Trinity College’s Park River Watershed Symposium held last fall, however, was that such a plan would be “monumentally expensive and politically difficult.”

The impassioned Mary Rickel Pelletier, river-walk leader and director of the Park River Watershed Revitalization Initiative, would be happy to see the river uncovered. More feasible, she says, though, is reconnecting city residents and visitors to the river through improving water quality and habitat along the above-ground sections and building walking and biking trails where appropriate as the consortium of organizations is doing along the south branch.

Recalling the Little River’s history helps explain why Pelletier and so many others remain so passionate about a waterway that has been nipped, tucked, and largely removed from sight. The city’s founding began on its banks; it powered the city’s industrial growth and at one point defined its western boundary, has served as its playground, and has done the city’s dirty work. The Little River was at the heart of Hooker’s settlement at the city’s founding. Today, the Little/Hog/Park River still is—even where we can’t see it.

Park River Watershed Revitalization Initiative

The Park River Watershed Revitalization Initiative (PRWRI) was formed in 2006 as a collaboration between the Farmington River Watershed Association and an ad hoc network of local stakeholders coordinated by Mary Rickel Pelletier to provide long-term stewardship of the Park River watershed. The two watersheds have common interests: they overlap across seven town boundaries and share municipal ordinances that define land-use policies. In 2007, PRWRI worked with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to showcase an Urban River Restoration Conference at the state Legislative Office Building and partnered with Trinity College to hold a Park River Watershed Symposium. PRWRI sponsored river clean-ups in Hartford and West Hartford and led river walks co-hosted with Hartford Preservation Alliance and in celebration of the 5th anniversary of HOG RIVER JOURNAL. In 2008 PRWRI will begin working with Fuss & O’Neill on a Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection Watershed Management Plan for the North Branch sub-basin. FRWA and PRWRI are also working with The Children’s Museum on the Park River Assessment Program, which will involve families in stream walks along local waterways.

To learn more visit www.parkriver.org

Explore!

“A River Runs Under It: A Hog River History” Fall 2002

Read more stories about environmental history on our Topics page.