By Briann Greenfield with Beth Burgess

By Briann Greenfield with Beth Burgess

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

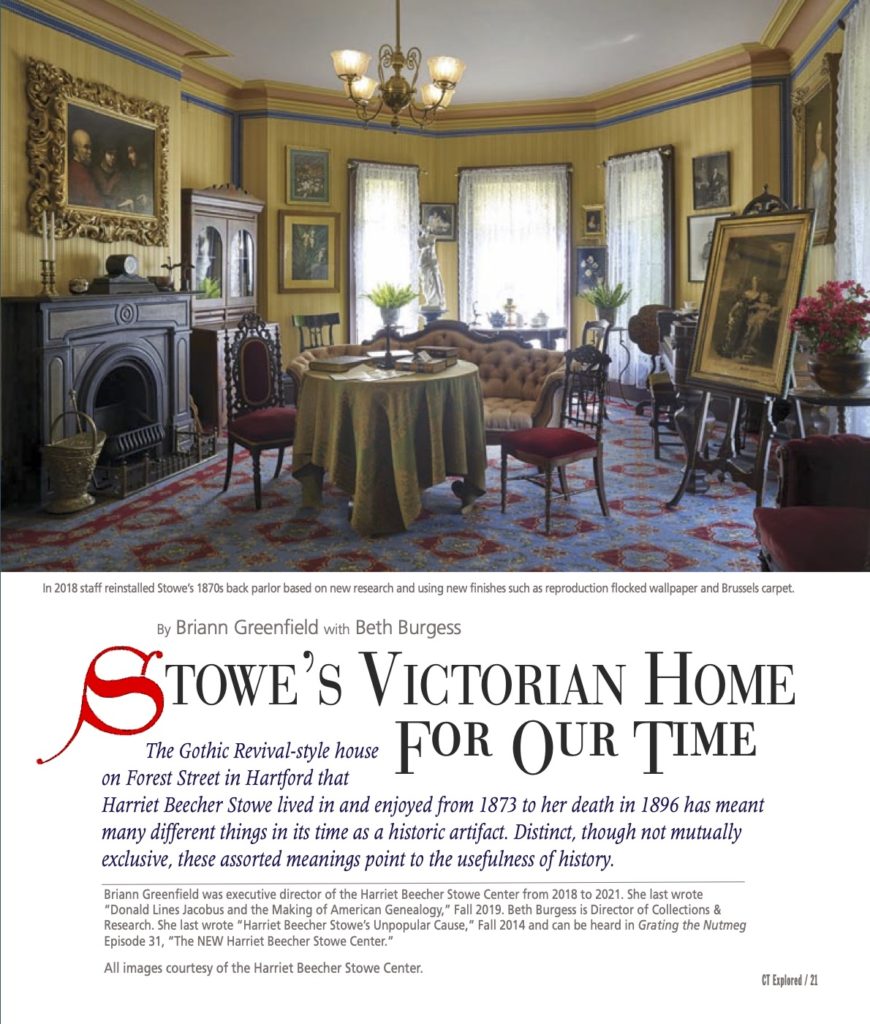

The Gothic Revival-style house on Forest Street in Hartford that Harriet Beecher Stowe lived in and enjoyed from 1873 to her death in 1896 has meant many different things in its time as a historic artifact. Distinct, though not mutually exclusive, these assorted meanings point to the usefulness of history.

Perhaps the first person to grapple with the meaning of the house was Stowe’s grandniece, Katharine Seymour Day (1870-1964). Day, a professionally-trained artist and an activist in reform movements of the Progressive era, purchased the house in 1924 with the intention to restore it to the period of her great-aunt’s residency. Her goal was personal, at least at first: to commemorate her prominent early Connecticut family.

Day lived in the house as she assembled a substantial collection of family papers, household furnishings, and memorabilia associated with her famous aunt. In 1941 Day incorporated the site as a foundation, and, by subsequently providing for it in her will, established the organization that exists today.

In many ways, it is remarkable that she preserved a place associated with abolition at the time she did. Nationally, the 1920s was an era of heightened racism marked by the erosion of civil rights gained during Reconstruction, anti-black violence, lynchings, and legal racial discrimination. Three years before Day purchased the house, Charles S. Johnson, a prominent African American sociologist, reported on conditions among Black residents in Hartford, recording the impact of housing segregation and employment discrimination. Johnson paid considerable attention to the changing demographics in Hartford’s Black community caused by the tobacco industry’s recruitment of Black families from Georgia to work in the fields. He recognized that these new migrants, conspicuous because of their rural customs and manners, were entering a social order hardened against newcomers after decades of Eastern European immigration. Indeed, in 1922 and 1924, as Herbert F. Janick Jr. writes in A Diverse People: Connecticut 1914 to the Present (Pequot Press, 1975), the Ku Klux Klan staged a series of open rallies in Connecticut.

The degree to which Day recognized the relevance of her great-aunt’s anti-slavery work to these political and cultural debates is not clear. Over time the work of preservation and collecting provided Day with additional opportunities to explore her personal past. She acquired a 17th century foot warmer owned by her Hooker ancestors, a Queen Anne-style highboy evocative of the Connecticut River Valley, and the Andrew Kingsbury Collection of 18th-century Connecticut legal documents. When it came time to incorporate her foundation, Day chose a name that expressed her family focus: the Stowe-Beecher-Hooker-Seymour-Day Memorial Library and Historical Foundation.

Day’s family history, though, didn’t provide a lasting interpretive frame. Seminal in shaping the next vision was Joseph Van Why. Van Why arrived in 1955 to work as Day’s private cataloger. As he recounted for a 1992 newsletter, his Dutch, English, and French Huguenot pedigree helped get him the job. Learning the cataloging and curatorship job skills required would come later.

Joseph Van Why’s watercolor sketch of a recreated front parlor, c. 1965. Van Why includes Stowe and Beecher furnishings placed according to information found in Stowe’s letters and domestic guide books, newspaper articles, and photographs. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford

With Day’s death in 1964, Van Why became the foundation’s curator, rising to the position of executive director in 1969, a role he held for 23 years until his retirement in 1992. During those years, Van Why conducted the first primary-source research and collaborated on the Stowe house restoration with first director Bill Warren, who led the organization from 1965 to 1969. He also oversaw interpretation, processed more than 200,000 manuscript items, the majority related to Stowe, her extended family, and neighboring residents of Nook Farm, and built a modern underground archives facility to hold them all. Those projects focused Van Why, who also served briefly and concurrently as executive director of the Mark Twain House from 1970 to 1974, on the Victorian period in a way that Day had not.

The project to open the house to the public, as it did in 1968, meant identifying appropriate period furnishings, searching for period wallpapers, and assembling multiple sets of period china for the construction of seasonal displays. The archival work gave Van Why intimate knowledge of everyday life at Nook Farm. It may be surprising that the Stowe House was one of the first Victorian house museums in the country. Victorian decorative arts and architecture was just gaining acceptance as worthy of preservation in the 1950s and 1960s. Carl W. Drepperd’s 1950 collecting manual, Victorian, The Cinderella of Antiques (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co.), makes this fact evident, damning Victorian furnishings with faint praise and promising to distinguish between the “premium” and more prevalent “junk.”

Van Why’s embrace of the Victorian era coincided with a perceived period of decline in Hartford. The 1960s was a period of suburbanization, white flight, and corporate exodus. In a sense, a turn to the Victorian past could function as an escapist nostalgia for a time when the city could boast industrial wealth and nationally prominent citizens like Stowe and Twain. But the elevation of Hartford’s Victorian past could also be read as a defense of the urban environment, a la Jane Jacobs, the prominent urbanist and activist, who rejected urban renewal and so-called “slum clearance,” arguing that dense urban neighborhoods built in the late-Victorian period strengthened social networks and community life. Van Why quietly supported Hartford cultural leaders, including those at the Wadsworth Atheneum and the Mark Twain House, who sought to promote Victorian Hartford as a heritage tourism destination and with it a source of revenue for city businesses.

Van Why was followed by Jo Blatti, who arrived at the Stowe Center in 1992 and whose tenure brought a new focus for interpreting Stowe’s story. Blatti shifted to looking at Stowe through the lens of women’s history, drawing on emerging scholarly approaches in cultural studies and contemporary feminist theory that reclaimed the work of 19th-century women writers previously derided by literary critics as overly sentimental. Emblematic of this scholarly turn was Joan Hedrick’s 1994 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life (Oxford University Press). Women’s history brought many female visitors to the Stowe Center who discovered in Stowe a then-rare historical hero with whom they could relate. Stowe struggled to find her voice and power in a social order that consigned women to the home in ways tellingly familiar.

In 1994 the Stowe Center Board of Trustees, chaired by Beecher descendant Norman Beecher, set a new institutional mission that formalized the organization’s separation from the subject of aesthetics or design. “This organization started as a conservator of real estate and artifacts,” Beecher began in a newsletter that year. “But Mrs. Stowe was not famous for her property. She and her family were famous for their ideas.” As Beecher went on to explain, the newly renamed Harriet Beecher Stowe Center would become more of an educational institution and employ its “intellectual treasure,” as Beecher wrote, to illuminate “burning contemporary issues which Mrs. Stowe and family would challenge if they were alive today.”

Led by executive director Katherine Kane, the Stowe House was reinterpreted in 2017 to include modern contextual exhibits, multimedia, and interactive experiences that connect Stowe’s antislavery motivation and the impact and legacy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin to inequities we still face today. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford

The trustees’ charge was realized by visionary executive director Katherine Kane, who led the Stowe Center from 1998 to 2018 and who accomplished the first major restoration and reinterpretation of Stowe’s House since 1968. Bridging the gap between “real estate” and “intellectual treasure,” Kane broke new ground in the historic house museum field by adopting a major reinterpretation of the visitor experience, one that uses the house as a platform not only to explore Stowe’s motivation for becoming an anti-slavery activist but to provide opportunities for visitors to explore what motivates them to act on social issues they care about.

Every generation understands Stowe’s story in new ways, and this is especially true as we enter a period of heightened racial justice activism. The end of slavery was not the end of racial oppression, and the years between the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852 and Stowe’s death in 1896 can tell us a lot about how racism has persisted and thrived. In bridging the Victorian and early modern period with its popularity, Uncle Tom’s Cabin both carried forward old forms of racism and created new forms. Stowe opposed slavery using a form of Victorian sentimental fiction that encouraged feelings—calling on her white readers to open their hearts and feel the plight of enslaved men and women. Stowe also based her claim for the humanity of enslaved men and women on their ability to feel, to bring Christ into their hearts, and to practice morality. But Victorian religious culture also linked morality and godliness to innocence and childhood, qualities that passed into the modern age as markers of inferiority and passivity. That the words “Uncle Tom” are now most closely associated with the idea of a race traitor derives from this Victorian conceit.

While grounded in Victorian thought, Uncle Tom’s Cabin ushered in the modern forms of commercialization and commodification. The bestselling novel of the 19th century achieved even larger audiences as a dramatic adaptation in minstrel shows, vaudeville, and eventually film. The book also inspired merchandise—vases, wallpaper, Currier & Ives prints—to decorate the home, none of which Stowe benefited from financially. Produced by their makers with the intention of achieving market sales, these popular culture adaptations frequently eschewed the noble humanity of Stowe’s titular character, finding greater profits by portraying him as an emasculated grandfather figure or a buffoon. There is perhaps no greater evidence of the racism of the day than these revealed by the market. [See “Re: Collections: A Tomitude,” Fall 2002.]

Thanks to Katharine Seymour Day’s initial efforts, the Stowe Center today preserves collections that give insight into the legacy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the ways in which Stowe’s radical insistence on empathy and understanding was recast and re-appropriated. Racist assumptions, whether they are located in Stowe’s novel or in commercialized knockoffs, must not go unacknowledged. However, these documents of the past provide an opportunity to identify racism, understand how it functions, and deepen our awareness of its contemporary manifestations. In that sense, remnants of Victorian Hartford have a role to play in dismantling the mistakes of the past and building a more just future.

Briann Greenfield was executive director of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center from 2018 to 2021. She last wrote “Donald Lines Jacobus and the Making of American Genealogy,” Fall 2019. Beth Burgess is Director of Collections & Research. She last wrote “Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Unpopular Cause,” Fall 2014 and can be heard in Grating the Nutmeg Episode 31, “The NEW Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

This is one in a series of stories funded in part by Hartford Foundation for Public Giving about the history of nonprofits that operate in the Greater Hartford region.

Explore!

Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

77 Forest Street, Hartford

harrietbeecherstowecenter.org, 860-522-9258

“Re: Collections: A Tomitude,” Fall 2002

Summer 2011: The entire issue celebrates Stowe’s 200th birthday.

“Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Unpopular Cause” By Beth Burgess. Fall 2014

“Lincoln and the Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin” by Katherine Kane. Winter 2012/2013

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 31, “The NEW Harriet Beecher Stowe Center”

GO TO NEXT STORY

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!