By James Boylan and Betsy Wade

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2019

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

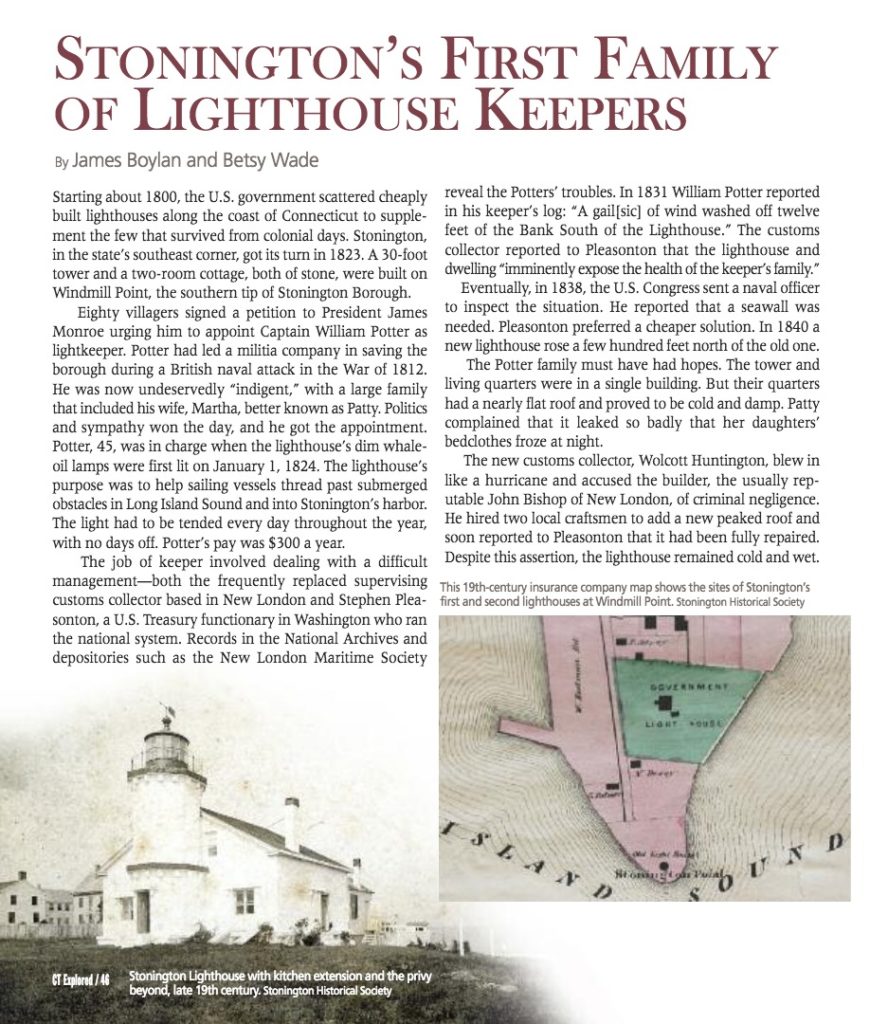

Starting about 1800, the U.S. government scattered cheaply built lighthouses along the coast of Connecticut to supplement the few that survived from colonial days. Stonington, in the state’s southeast corner, got its turn in 1823. A 30-foot tower and a two-room cottage, both of stone, were built on Windmill Point, the southern tip of Stonington Borough.

Eighty villagers signed a petition to President James Monroe urging him to appoint Captain William Potter as lightkeeper. Potter had led a militia company in saving the borough during a British naval attack in the War of 1812. He was now undeservedly “indigent,” with a large family that included his wife, Martha, better known as Patty. Politics and sympathy won the day, and he got the appointment.

Potter, 45, was in charge when the lighthouse’s dim whale-oil lamps were first lit on January 1, 1824. The lighthouse’s purpose was to help sailing vessels thread past submerged obstacles in Long Island Sound and into Stonington’s harbor. The light had to be tended every day throughout the year, with no days off. Potter’s pay was $300 a year.

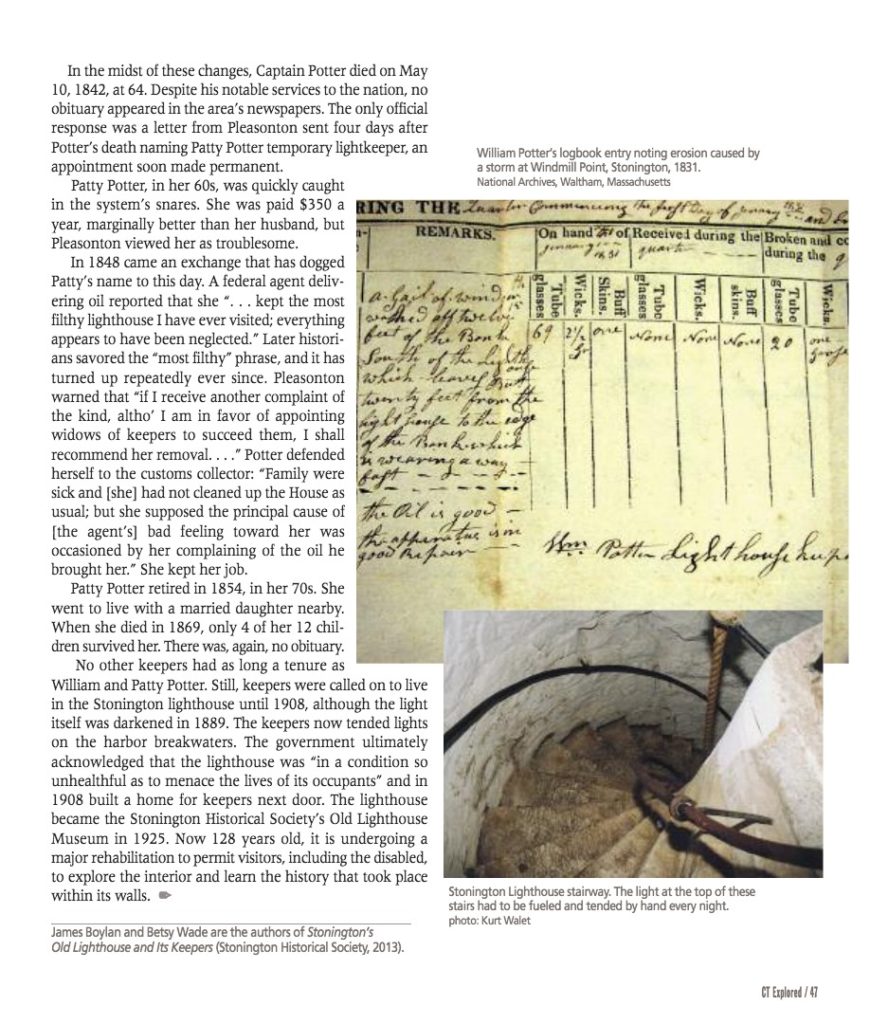

The job of keeper involved dealing with a difficult management—both the frequently replaced supervising customs collector based in New London and Stephen Pleasonton, a U.S. Treasury functionary in Washington who ran the national system. Records in the National Archives and depositories such as the New London Maritime Society reveal the Potters’ troubles. In 1831 William Potter reported in his keeper’s log: “A gail[sic] of wind washed off twelve feet of the Bank South of the Lighthouse.” The customs collector reported to Pleasonton that the lighthouse and dwelling “imminently expose the health of the keeper’s family.”

Eventually, in 1838, the U.S. Congress sent a naval officer to inspect the situation. He reported that a seawall was needed. Pleasonton preferred a cheaper solution. In 1840 a new lighthouse rose a few hundred feet north of the old one.

The Potter family must have had hopes. The tower and living quarters were in a single building. But their quarters had a nearly flat roof and proved to be cold and damp. Patty complained that it leaked so badly that her daughters’ bedclothes froze at night.

The new customs collector, Wolcott Huntington, blew in like a hurricane and accused the builder, the usually reputable John Bishop of New London, of criminal negligence. He hired two local craftsmen to add a new peaked roof and soon reported to Pleasonton that it had been fully repaired. Despite this assertion, the lighthouse remained cold and wet.

The new customs collector, Wolcott Huntington, blew in like a hurricane and accused the builder, the usually reputable John Bishop of New London, of criminal negligence. He hired two local craftsmen to add a new peaked roof and soon reported to Pleasonton that it had been fully repaired. Despite this assertion, the lighthouse remained cold and wet.

In the midst of these changes, Captain Potter died on May 10, 1842, at 64. Despite his notable services to the nation, no obituary appeared in the area’s newspapers. The only official response was a letter from Pleasonton sent four days after Potter’s death naming Patty Potter temporary lightkeeper, an appointment soon made permanent.

Patty Potter, in her 60s, was quickly caught in the system’s snares. She was paid $350 a year, marginally better than her husband, but Pleasonton viewed her as troublesome.

In 1848 came an exchange that has dogged Patty’s name to this day. A federal agent delivering oil reported that she “. . . kept the most filthy lighthouse I have ever visited; everything appears to have been neglected.” Later historians savored the “most filthy” phrase, and it has turned up repeatedly ever since. Pleasonton warned that “if I receive another complaint of the kind, altho’ I am in favor of appointing widows of keepers to succeed them, I shall recommend her removal. . . .” Potter defended herself to the customs collector: “Family were sick and [she]had not cleaned up the House as usual; but she supposed the principal cause of [the agent’s]bad feeling toward her was occasioned by her complaining of the oil he brought her.” She kept her job.

Patty Potter retired in 1854, in her 70s. She went to live with a married daughter nearby. When she died in 1869, only 4 of her 12 children survived her. There was, again, no obituary.

No other keepers had as long a tenure as William and Patty Potter. Still, keepers were called on to live in the Stonington lighthouse until 1908, although the light itself was darkened in 1889. The keepers now tended lights on the harbor breakwaters. The government ultimately acknowledged that the lighthouse was “in a condition so unhealthful as to menace the lives of its occupants” and in 1908 built a home for keepers next door. The lighthouse became the Stonington Historical Society’s Old Lighthouse Museum in 1925. Now 128 years old, it is undergoing a major rehabilitation to permit visitors, including the disabled, to explore the interior and learn the history that took place within its walls.

No other keepers had as long a tenure as William and Patty Potter. Still, keepers were called on to live in the Stonington lighthouse until 1908, although the light itself was darkened in 1889. The keepers now tended lights on the harbor breakwaters. The government ultimately acknowledged that the lighthouse was “in a condition so unhealthful as to menace the lives of its occupants” and in 1908 built a home for keepers next door. The lighthouse became the Stonington Historical Society’s Old Lighthouse Museum in 1925. Now 128 years old, it is undergoing a major rehabilitation to permit visitors, including the disabled, to explore the interior and learn the history that took place within its walls.

James Boylan and Betsy Wade are the authors of Stonington’s Old Lighthouse and Its Keepers (Stonington Historical Society, 2013).

Explore!

Old Lighthouse Museum

7 Water Street, Stonington

Stonington Historical Society

Two if by Sea: New London’s Harbor Light and Stonington’s Old Lighthouse Museum, Summer 2010

Kate Moore: Keeper of the Fayerweather Lighthouse in Bridgeport, Spring 2009

For Kids: Maritime Village — Stonington Borough

Lesson Plan for Grades 3-4: Maritime Village — Stonington Borough