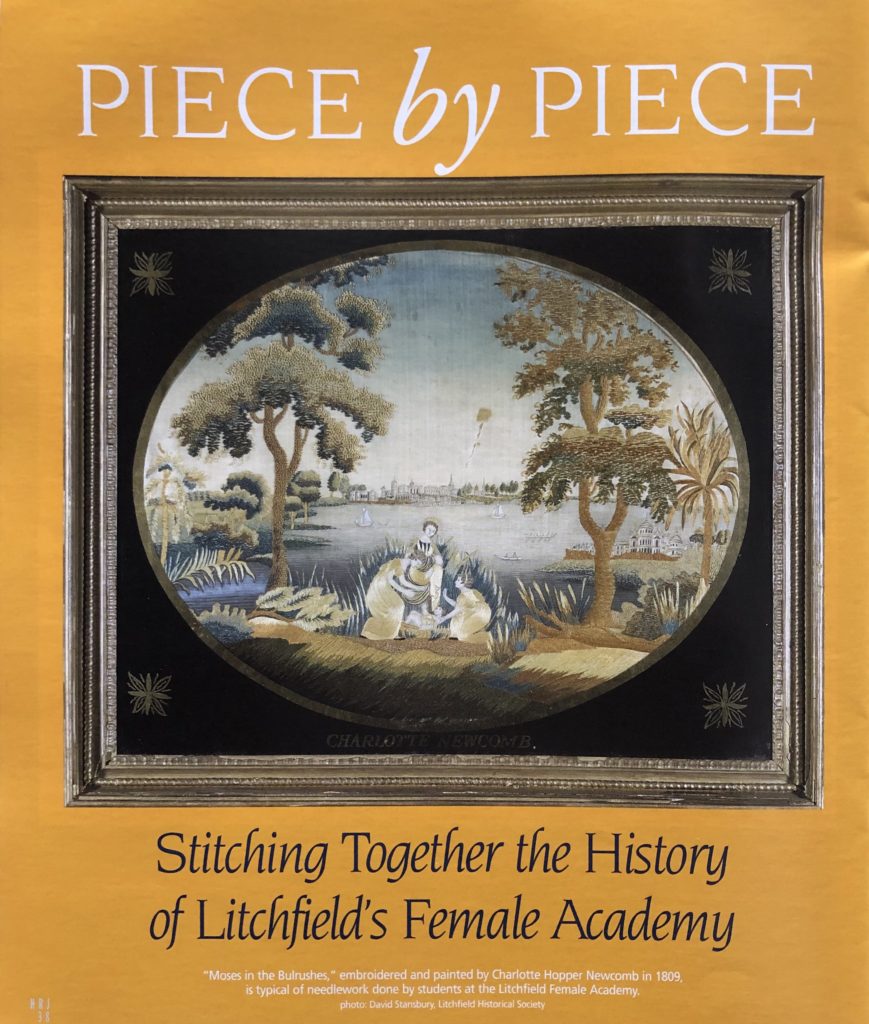

Charlotte Hopper Newcomb, “Moses in the Bulrushes,” 1809. photo: David Stansbury, Litchfield Historical Society

By Lynne Brickley

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The Litchfield Historical Society (LHS) is continually on a detective hunt to fill gaps in the already well-documented history of Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy. The school’s history is unique in that it is in large part told in the words and works of the students themselves, while most institutional histories are written almost exclusively from the perspective of founders and administrators and based more upon intentions and hopes than reality. The vivid sense we get of the academy’s impact on the lives of its students is revealed through their writings, art, and needlework, which were scattered as alumnae and their families settled throughout the country. The LHS has for years been working to trace materials connected with the academy, and, through dogged detective work—as well as occasional sheer serendipity—has been fortunate to reclaim many items that enhance and embellish our understanding of the school.

The Litchfield Female Academy, founded in 1792, was remarkable not only in that it lasted for more than 40 years, but also in its enrollment of an estimated 3,000 students from throughout the country, Canada, and the West Indies. Sarah Pierce began the school in her family home as a means of supporting her widowed stepmother and younger siblings. Her brother John Pierce, who had been the assistant paymaster of the Continental Army during the Revolution, had sent Sarah to New York City specifically to train to become a teacher in hopes of lessening his financial responsibilities to the family. After John Pierce’s untimely death, Sarah Pierce decided to open her own school, employing various members of her family in the venture.

Sarah Pierce, attributed to George Catlin, c. 1820. photo: David Stansbury, Litchfield Historical Society

Little did Pierce anticipate her school’s immediate success. So many students enrolled that the school outgrew its space in the family home. In 1798 she convinced the leading men of Litchfield to hold a subscription drive to finance construction of an Academy building. The men demonstrated their belief in Pierce’s managerial abilities by allowing her total independence, rather than forming a governing body of trustees to protect their investment.

At its peak in 1816, the school’s enrollment reached 157. In 1828, as the school was in decline, it was incorporated under a board of trustees, which erected a new Academy building in hopes of attracting increased enrollment.

Republican Motherhood

Just after the American Revolution, numerous American writers called for improvements in female education, using the rhetoric of what’s now called “Republican Motherhood.” They argued that all free, white American males required proper moral and intellectual training to become informed voters and that women, who had the earliest and greatest influence on children, needed improved educational opportunities to become “mothers of the sons of Democracy.”

To that end, Pierce continually expanded the school’s academic curriculum. But while she introduced many subjects not usually taught to women, Pierce maintained the ornamental subjects of art and needlework that were still demanded by the families who sent their daughters to academies.

Pierce played a crucial role in training teachers and founders of other women’s schools. She hired numerous assistants, at least 50 of whom went on to careers in education. In 1800 Pierce accompanied her niece Idea Strong to Vermont to help her establish the Middlebury Female Academy, which after Strong’s death was later taken over by Emma Hart of Connecticut, later the founder of Emma Willard’s Seminary in Troy, New York. Litchfield student and assistant teacher Catharine Beecher founded the Hartford Female Seminary in 1823, and other alumnae founded and taught in schools in at least 12 states.

Several Academy students went on to careers as writers, notably Harriet Beecher Stowe the novelist, Abigail Goodrich Whittelsey, who founded and edited Mother’s Magazine, the first periodical for mothers in the United States, and Louisa Caroline Huggins Tuthill, best known for her 1830 publication Ancient Architecture, the first architectural history published in America, and also the author of more than 20 books for young people and an editor of The Young Lady’s Reader.

Piecing Together the Past

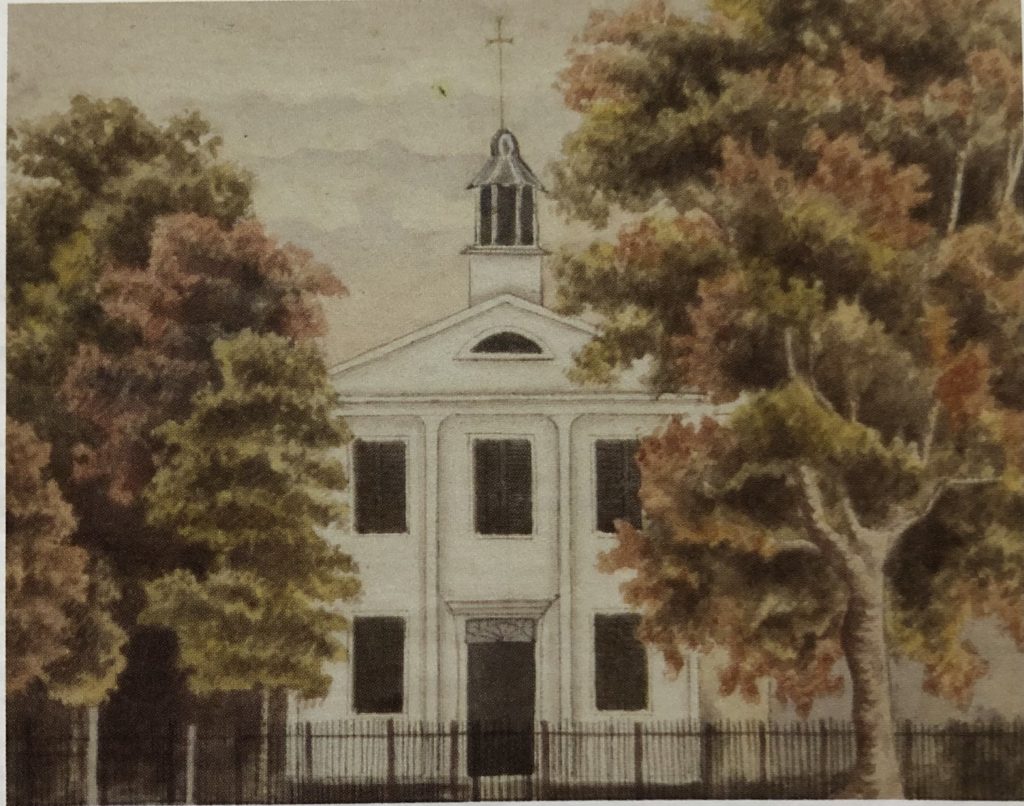

Emily Noyes Vanderpoel, Litchfield Female Academy, watercolor, c. 1890. photo: David Stansbury, Litchfield Historical Society

The needlework, paintings, and manuscripts acquired since a major 1993 exhibition on the school by the LHS strengthen the society’s ability to document and interpret the fascinating history of the school. The true strength of the collection is that it allows cross-referencing of information from the manuscript sources to the art and needlework, providing an unusually rich context and bringing to life in greater detail the experience of the students who attended.

The first major research into the history of the school was undertaken in the late 19th century by Emily Noyes Vanderpoel, a seasonal resident of Litchfield and a descendant of the town’s famed Revolutionary hero Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge. Vanderpoel, several of whose ancestors had attended the academy, was a major donor to and the curator of the LHS. She used her family and social connections to track down elderly alumnae and their families. She collected and transcribed records, student journals, letters, compositions, correspondence, and personal reminiscences. She also traced numerous works of art and needlework done by students at the school. Vanderpoel published two volumes of the materials she collected, Chronicles of a Pioneer School in 1903 and More Chronicles in 1927.

As informative as the Vanderpoel volumes are, they are indeed “Chronicles,” typical of the work of late 19th- and early 20th-century local antiquarians, with no interpretation or analysis of the role of the school; nor do they place the school in the context of women’s education of the period. They also suffer from somewhat erratic editing changes and more than a little local false boosterism, including claims that Sarah Pierce’s school was the “first” for women in the United States. In fact, other well-known female academies had been founded before the Litchfield school; several of them, including the Bethlehem Female Seminary in Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Young Ladies Academy, had large enrollments drawn from many states and offered an array of academic as well as ornamental subjects.

In 1993 the LHS mounted an exhibition about the school, based upon new scholarly research. The project included the publication of To Ornament Their Minds: Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy, 1792 -1833. The exhibition, programming, and publicity elicited a flurry of new information about the school.

Vanderpoel had included some 1,200 names of students on her lists. By the time of the 1993 exhibition catalogue, an additional 500 students had been identified. The society also made biographical information on many of the pupils available to the public during the exhibition. Those lists were, however, known to be incomplete. The recent availability of websites with online genealogies, local histories, and vital statistics has made the proper identification of students a much easier and rewarding task.

The tremendous geographical mobility of families of the period had previously created difficulties in tracing students who may have been born, lived, and died in a succession of different states. For instance, needlework expert Glee Krueger, a consultant for the 1993 exhibition and catalogue, located a silk embroidery mourning picture in the collections of Old Sturbridge Village. The maker of this memorial to “William Card, Esqr” could not be traced. Digital sources now reveal that the piece was stitched by Anna Maria Holmes, who attended the academy in the 1820s from Fairfield, in Herkimer County, New York, as a memorial to her maternal grandfather, who had been born in Rhode Island, moved to Herkimer County and died in Ohio.

In another instance, a simple misspelling had prevented the tracing of four sisters of the Orton family who had attended the school. They were listed as being from Wingfield, New York, which is on Staten Island, and their family could not be found. An online genealogy now reveals they were actually from Winfield in Herkimer County, New York, and provides excellent family information.

The growth of the Internet has made it much easier to find art and needlework held by dealers and auction houses. Recently, a local collector purchased a sampler from eBay with the inscription “Esther H. Morse, Sampler Wrought in the 15 Year of her Age 1828.” The building in the bottom center of the sampler may be of the original 1798 Litchfield Female Academy, of which there is no known image.

Glimpses of Lives Lived

In 1998 the LHS undertook a major project to transform its Tapping Reeve House and Litchfield Law School building into an interpretive exhibition that would tell the story of the early law school and its students. Founded in 1774, the law school drew almost one thousand young men to Litchfield before it closed in 1833. Research on the law students was also somewhat of a watershed for new information on Sarah Pierce’s students. Forty-five new names of female academy students were found, often in biographies of the law students. We learned that law student Henry Baldwin, later a U.S. Congressman and justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, met his wife, Marana Norton, “as a schoolgirl in Litchfield.” Patterns emerged of brothers, sisters and cousins traveling together from distant homes to attend the two Litchfield schools. There were at least 80 marriages between students of the two schools, creating a national network of couples with ties to Litchfield.

Last year the LHS obtained portraits of Jane Conard of the Philadelphia area and Oliver Stoughton Wolcott of Litchfield, the son and grandson of the two Governor Oliver Wolcotts of Connecticut. The couple met while attending the two Litchfield schools and were married in 1820 by the Rev. Lyman Beecher at Sarah Pierce’s house. Beecher performed the marriages of many student couples during his tenure as the town’s Congregational minister from 1810 to 1824. Purchased by the LHS, the portraits provide previously unknown images of a generation of the prominent Oliver Wolcott family and depict a couple representing both schools of Litchfield’s “Golden Age” of national prominence.

Descendants of law student Robert Gozman Rankin and his wife, academy student Laura Maria Wolcott, donated Laura’s elaborate sewing box, which she used while at the Litchfield Female Academy. The neo-classical sewing box with its removable fitted tray containing original carved-ivory sewing implements, is decorated in gold and black lacquer work and depicts a Chinese landscape. Although we know many students owned ornate sewing and paint boxes, which they mention in their writings, this is the first such object obtained for the collections of the LHS and shows the investment families made toward their daughters’ life-long application of skills learned at the Academy.

Knowledge through Needlework

Female academies of the early republic have been a topic of great interest to needlework scholars, who have provided the bulk of information on the schools, their founders, teachers, and scholars. Historians of education tend to ignore the academies—male, coeducational, and female—in their zeal to trace the seemingly inevitable rise of public high schools. Historians of American women have, for the most part, dismissed the academic importance of female educators of Pierce’s generation, focusing on the more famous school founders of the next, such as Catharine Beecher and Emma Willard, and the founders of the first colleges for women.

Laura Maria Wolcott’s sewing kit used while studying at the Litchfield Female Academy from 1814 – 1816. photo: David Stansbury, Litchfield Historical Society

Each additional piece of art or needlework documented or obtained by the LHS provides new insights to the Academy, its teaching methods and the ideals it promoted. The topics of the art and embroideries done by Pierce’s students were used to reinforce the lessons from classical, Biblical, and European history they studied, often stressing ideal feminine behavior. Differing versions of embroideries and art work, taken from the same sources, allow us to identify changes in the school’s instructors and subtle variations in motifs attributed to the academy by schoolgirl art and needlework experts.

Needlework of the early republic is best known by samplers young girls made as practice in stitching. Most girls stitched samplers under the instruction of their mothers or at local schools for young students. The majority of Sarah Pierce’s students had already mastered the basic stitching required to make a sampler and so spent their time in Litchfield producing the far more complicated large embroidery pictures for which female academies were known.

Pierce had her students embroider as they listened to their fellow students’ classroom recitations and readings. Nancy Hale, a student in 1802 from Glastonbury, Connecticut, wrote her sister that Miss Pierce “does not allow anyone to embroider without they attend to some study for she says she wished to ornament their minds when they are with her.”

The Vanderpoel volumes contained photographic images of needlework, some of which have never since been identified or located. One such work is “The Holy Family Returning from Egypt,” stitched by Esther Lyman of Middlefield, Connecticut, featuring an inscription in gold lettering on the black, painted glass mat, that read, “E. Lyman fecit Litchfield, 1802.” Recently the LHS obtained a strikingly similar undated piece by an anonymous maker. The center image of the “Holy Family” is identical and is obviously taken from the same print source, although Lyman’s is oval and the newly obtained one round in format. Although there are differences, there are enough similarities between the two pieces to attribute the newly discovered one to a student at the Litchfield Female Academy.

In 1996 needlework scholar Betty Ring discovered embroideries and watercolors done at the academy at the Salmon Brook Historical Society. They were the work of Hilpah, Mehetable, and Melissa Hays of Granby, students in the early 1800s. Identical pieces were known to have been done at the school, and one had appeared in the catalogue. Likewise, at least four identical versions of a piece called “The Cottage Girl” have been located, including one at the LHS and one at the Connecticut Historical Society, all from the same print source (which is also owned by the LHS) and all stitched by students in the early 1800s. More of these works are sure to exist, and we continue to search for them.

In 2002 the LHS obtained both an embroidery done at the Litchfield school and a journal kept by the same student, Charlotte Hopper Newcomb, of Pleasant Valley, Dutchess County, New York. This very rare find was partially a donation by a Newcomb descendant and partially a gift of a private donor. The journal revealed that Charlotte had also attended the school, along with her sister, Mary D. and seven of her first cousins who had already been identified as students.

The embroidery, stitched in 1809 and depicting “The Discovery of Moses in the Bullrushes,” had descended in the family. Charlotte frequently writes in her journal (a task Pierce required of all her students) of working on “her piece” and devotes time to it in school while listening to recitations of lessons by other young women. The piece is two-and-a-half feet wide by two feet tall; in its foreground, Pharaoh’s daughter and her handmaidens have just pulled the baby Moses in his basket from the river. The distant background features an oddly New England-like group of buildings.

To date some 30 pieces of art and needlework done at Pierce’s school have been located in the collections of 12 Connecticut museums and historical societies. Nine museums and historical societies in other states are also known to have Academy items. The Hugenot Historical Society in New Paltz, New York, for example, has a collection of nine art and needlework pieces done in Litchfield by the seven Bevier sisters who attended the Academy in the early 1800s. An additional 20 works believed to have been done at Pierce’s school have appeared in auction catalogues and antiques-dealer advertisements. The LHS would very much like to acquire better information about and images of these items to add to its documentation.

The LHS will continue to seek new information about women who attended Pierce’s school and any written records, art, and needlework done there. An estimated 500 to 1,000 students remain unidentified, especially those who attended between 1792 and 1814, when records first were kept. Many more paintings and embroideries, as yet not attributed to the school, are surely held in private collections, museums and historical societies throughout the country. The recent acquisitions make it clear that telling the full story of Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy, the young women who attended, and the impact of the school will be an ongoing process.

Lynne Templeton Brickley received her Ed.D. in History of Education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 1985. Her dissertation was the basis of the 1993 exhibition about Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy.

Explore!

The Litchfield History Museum and the Tapping Reeve House & Litchfield Law School

Open seasonally; Group tours are available all year by appointment

7 South Street, Litchfield

Litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org

“Litchfield’s Fortunes Hitched to the Stagecoach,” Spring 2008

“A New Life for the Merwinsville Hotel,” Spring 2020

“The Litchfield Congregational Meeting House,” Winter 2005/2006

“Civil War: Conflict in Litchfield,” Spring 2011

“Flying the Banner for Temperance,” Winter 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Sources

Emily Noyes Vanderpoel, Chronicles of a Pioneer School, from 1792 to 1833, Cambridge, MA, 1903 and More Chronicles of a Pioneer School, New York, 1927.

Lynne Templeton Brickley, “Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy, 1792 to 1833,” Ed.D. dissertation, Harvard University School of Education, 1985.

Theodore and Nancy Sizer, et. al., To Ornament Their Minds: Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy, 1792 to 1833, Litchfield, CT: The Litchfield Historical Society, 1993.

(To order the catalogue To Ornament Their Minds, please contact the Litchfield Historical Society at (860) 567-4501 or museumshop@litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org.)

Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers and Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850, 2 vols., NY: Knopf, 1993.

Eleanor H. Gustafson, “Collectors’ notes,” The Magazine Antiques, September 1996,

- 246.

For a full discussion on Charlotte Hopper Newcomb and her experiences at the

school see: Judith Livingston Loto, “One Voice: The Work and Words of Litchfield Female Academy Student Charlotte Hopper Newcomb, 1809 – 1810, in Peter Benes, et. al., “The Worlds of Children, 1620-1920,” The Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife Annual Proceedings 2002, pp. 65-77, Boston, MA: Boston University.