(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

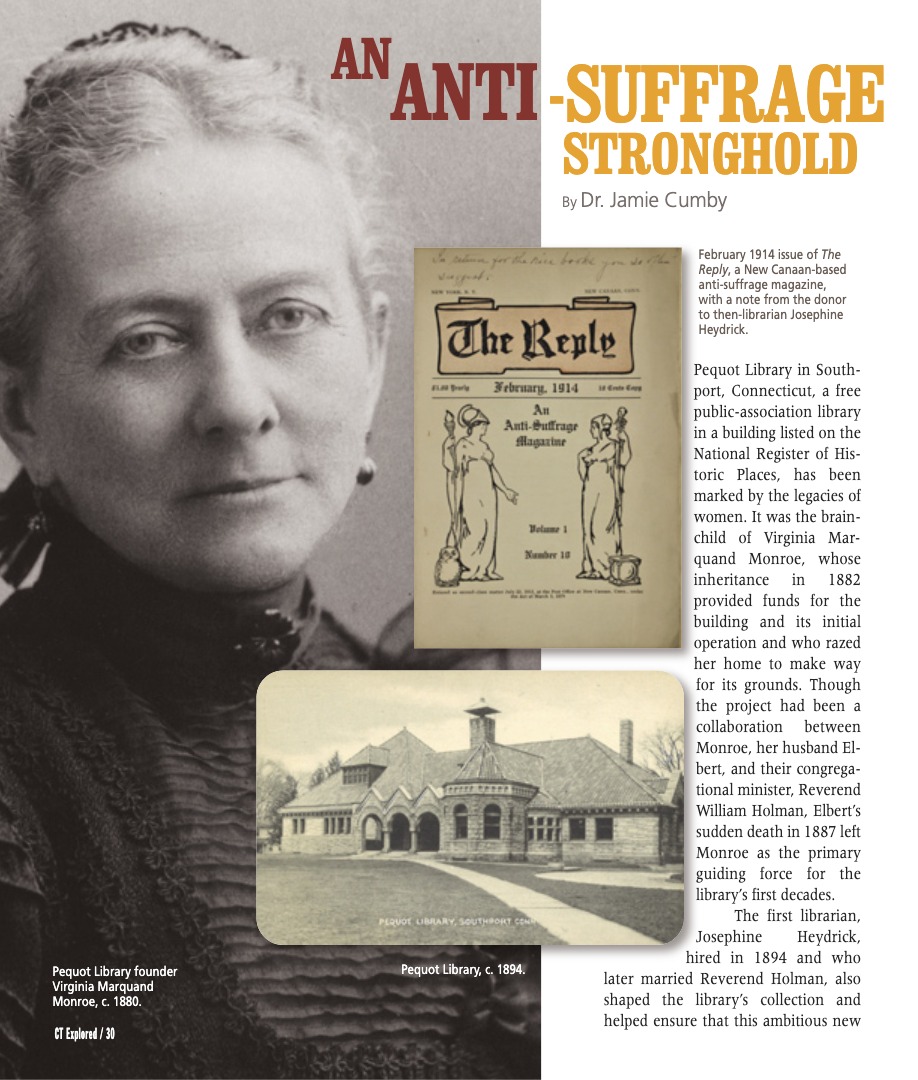

Pequot Library in Southport, Connecticut, a free public-association library in a building listed on the National Register of Historic Places, has been marked by the legacies of women. It was the brainchild of Virginia Marquand Monroe, whose inheritance in 1882 provided funds for the building and its initial operation, and who razed her home to make way for its grounds. Though the project had been a collaboration between Monroe, her husband Elbert, and their congregational minister, Reverend William Holman, Elbert’s sudden death in 1887 left Monroe as the primary guiding force for the library’s first decades.

The first librarian, Josephine Heydrick, hired in 1894 and who later married Reverend Holman, also shaped the library’s collection and helped ensure that this ambitious new venture turned into a successful cultural institution. Another prominent Southport woman, Mary Catherine Hull Wakeman, donated funds in 1898 for a new wing and a significant number of early printed books.

When Pequot Library formally opened its doors in 1894, suffragist foment had already been a core social and political issue in Connecticut for nearly 30 years. Just the year before, the Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association had won a victory when women gained the right to vote for school officials. However, the entrenched strength of political opposition to suffrage from the state’s Republican government kept these gains modest at best, and Connecticut lagged behind states like Wyoming.

As we memorialize the work of suffrage activists in this era it is tempting to think about women-led institutions like Pequot with expectations that they were forces for empowerment and change. In reality, the library maintained gender-segregated reading rooms and stocked anti-suffrage books and leaflets. The picture we can reconstruct from the library’s early holdings and institutional archives shows the library’s complicated relationship with the changing position of women in society and a community divided as to how to confront “the woman question.”

Book-buying fell to the librarian, along with the library association’s Literature Committee. But, with a modest annual budget, the collection continued to depend on donations. Most of these donations came from Monroe, who, in consultation with Holman, continued to contribute Americana, genealogical books, and other research materials until her death in 1926. But she also sent books about contemporary issues, such as Catherine Beecher’s anti-suffrage treatise Woman Suffrage and Woman’s Profession (Brown & Gross, 1871). Beecher’s book was at home on the shelves with similar works like Margaret Sangster’s Winsome Womanhood (Fleming H. Revell Company, 1900), donated to the library by Oliver Gould Jennings, brother of Fairfield’s most prominent anti-suffragist Annie Burr Jennings.

An interesting change took place in the early 1910s, when the library association started buying books that explicitly encouraged women’s careers, such as Helen Marie Bennett’s Women and Work: The Economic Value of College Training (D. Appleton & Company, 1917) and Annie Marion Maclean’s Wage Earning Women (The Macmillan Company, 1910). There is room to draw a parallel between the growing collection of books aimed at educated, working young women and changes in the library’s patrons. Several young women who had grown up with the library, including Reverend Holman’s daughters Ruth and Clara and future Pequot librarian Helen Bradley, had recently completed advanced degrees.

However, the library had not truly embraced a progressive stance. One of the most intimate and telling pieces of evidence is a handwritten note on a copy of The Reply (1914), an anti-suffrage periodical edited by New Caananite Helen S. Harmon-Brown. The note, apparently addressed to Heydrick, reads, “In return for the nice books you so often suggest.” Even if young women patrons were embracing suffragette literature, Heydrick, who would continue to be the librarian until 1917, was actively promoting anti-suffrage materials.

Though Pequot Library was an institution founded by a woman and staffed by women, neither of these things was necessarily incompatible with an anti-suffrage platform. Susan E. Marshall, in Splintered Sisterhood: Gender and Class in the Campaign against Woman Suffrage (University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), has debunked the idea that the anti-suffrage position was a passive one. The “antis” trafficked in the kind of elite networks to which much of Southport belonged. Many of the library’s anti-suffrage leaflets, including its copies of The Reply, argued that the suffrage movement would hurt the effectiveness of womens’ public philanthropic work (such as projects like founding a free library) by distracting them with politics. Pequot Library ultimately reflected the demands and interests of its patrons and founders, who were, in this case, key targets of anti-suffrage rhetoric.

Jamie Cumby is special collections librarian at Pequot Library.

Explore!

Pequot Library

720 Pequot Avenue, Southport

pequotlibrary.org

Read all of our stories about Women’s Suffrage on our TOPICS page.