(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Between 1998 and 2002 Greenwich Historical Society undertook a dual interpretation of its Bush-Holley House. The house was refurnished to interpret two historic periods in recognition of its role as home to three generations of the Bush family (with a focus on the 1790 to 1825 era) and its later national significance as the Holley family’s boarding house for the Cos Cob art colony between 1890 and 1920.

Interpreting the houses’ slave history and Connecticut’s gradual emancipation laws was always an essential part of the furnishing plan which called for placing objects in each of the master’s rooms to represent domestic chores performed by enslaved workers Phyllis and Candis and the labor of their sons, Cull and Jack. However, new research and vision by the curatorial team led by Karen Blanchfield White and Kathleen Craughwell-Varda convinced the historical society to make the important decision to present the kitchen attic for the first time as a slave quarter.

The use of this wing as slave quarters had long been part of the oral tradition of Bush-Holley House, but it lacked research to substantiate it. The staff’s knowledge of the family and people enslaved in the Bush household comes from primary-source evidence in deeds, wills, inventories, and census records. Those records indicate that in 1738 Justus Bush, a merchant, purchased the circa 1730 house and that his son David moved into it around the time of his marriage to Sarah Isaacs in 1755. David Bush’s 1797 probate inventory lists 10 slaves by name. By the 1820 census four African Americans remain in the household run by David’s widow and second wife Sarah Scudder Bush and their son Justus Luke Bush.

The earliest documentary evidence pointing to a slave quarter at the house was a deposition in the Connecticut State Archives’s Revolutionary War Series from 1785 that mentions a “back kitching,” which physical evidence indicates David Bush had attached to the house circa 1771. Architectural historian James Sexton noted in a 2000 historic structure report that a staircase, removed by the historical society in the 1960s, once connected the back kitchen to the chamber (attic) above and would have provided “the slaves with a more private way to move through the whole house, indicating a rational reorganization of the house into two different spheres: that of the master and slave.”

Northern slave narratives, such as those of Venture Smith in 1798 and Sojourner Truth in 1830, and inventories of Greenwich slave owners between 1790 and 1814 point to the use of attics and cellars as slave quarters. A 1739 inventory of Isaac Royall (Royall House and Slave Quarters, Medford, Massachusetts), records slave bedding in the kitchen and the “kitching chamber.” The Webb-Deane-Stevens Museum in Wethersfield also found documentation that a kitchen chamber in the Deane House was used as a slave quarter. “The Meaning of Absence: Household Inventories in Surrey County, Virginia, 1690-1715,” an essay by Anna L. Hawley published by the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife in 1989, provided a theory as to why the back kitchen and attic are not mentioned in David Bush’s probate inventory. Hawley writes that “much can be inferred from the absence of certain rooms and household goods from inventories, principally their lack of monetary value.”

For almost two decades the slave quarter in Bush-Holley House has provided a foundation for further exploration of Northern slavery through exhibitions, tours, public programs, and educational outreach. Today the historical society’s programs for middle-school students incorporate a tour of the slave quarter with an examination of primary source documents from the historical society’s archives.

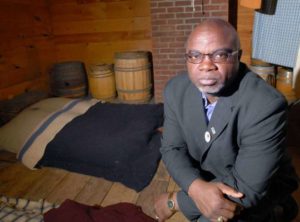

Joseph McGill in Bush-Holley House’s slave quarter, where he slept in 2012 as part of The Slave Dwelling Project. Greenwich Historical Society

Joseph McGill, former field officer of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and founder of The Slave Dwelling Project (slavedwellingproject.org), slept in Bush-Holley House’s slave quarter in 2012. The mission of his work is to raise awareness of the importance of preserving slave quarters in the U.S. by spending a night and recording his observations and impressions. After his stay McGill noted, “Once upon a time, you wouldn’t get that history at all. The fact that the space exists is a good thing.”

Debra Mecky is executive director and CEO of Greenwich Historical Society.

Explore!

Greenwich Historical Society

47 Strickland Road, Cos Cob

Greenwichhistory.org, 203-869-6899

Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa, Winter 2012-2013

Adam Jackson’s Story Revealed, Spring 2013. CT Landmarks has also recreated the space where Adam Jackson, enslaved by the Hempsted family for 30 years, likely lived in the Hempsted House.

Read more stories about the long arc of the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.