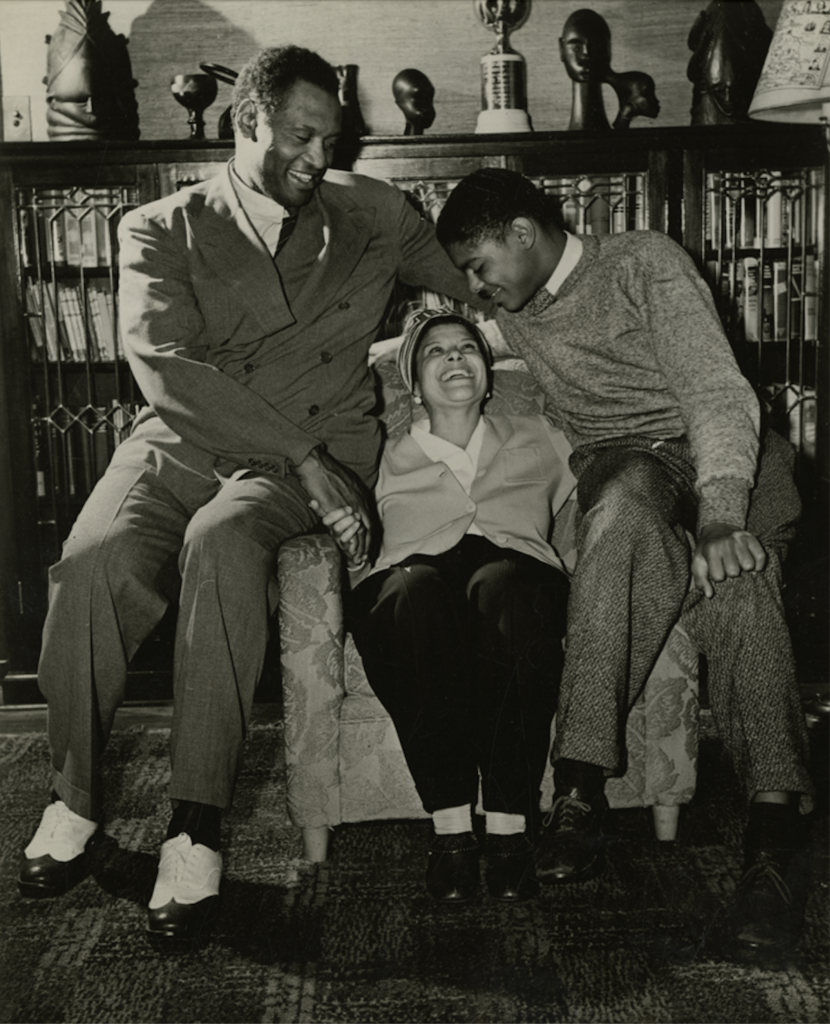

Paul and Eslanda Robeson with their son Paul Jr., Enfield, c. 1950. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

By Steve Thornton

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Paul Robeson, world famous actor, singer, and activist, was of course not the first celebrity to move to Connecticut. But perhaps unlike many others, when Robeson and his family moved to Enfield in 1941, they were being surreptitiously followed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

The federal government had identified the Robesons as threats to national security because of their outspoken political views. Paul Robeson and his wife, Eslanda Goode Robeson (known as Essie), a journalist, anthropologist, and traveler throughout much of the African diaspora, spoke out against Jim Crow racism in America, the rise of fascism in Spain and Germany, colonialism in Vietnam and South Africa, and the dreaded possibility of nuclear war with the Soviet Union. This activity put them on FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s list of subversives, and they were secretly surveilled by governments at home and abroad, FBI records reveal.

It seemed likely that their relocation to Connecticut from New York would provide a refuge for their son Pauli, who attended Enfield’s public schools, as The Hartford Courant’s July 27, 1941 interview with Paul suggested. But their 12 years here, from 1941 to 1953, were tumultuous. After receiving death threats in 1949, Essie installed a home alarm system and kept a hunting knife beside her bed, according to Martin Duberman in Paul Robeson (Knopf, 1989.)

From the family’s base in Enfield, Paul continued to sing, record, act in movies, and perform on Broadway. In 1945 TheCourant reported that his appearance at The Bushnell Memorial in Hartford drew an enthusiastic full house. “Mr. Robeson comes to the stage very much a popular hero,” noted the concert review. “He is a great figure of a man.”

On March 15, 1944, Eslanda spoke at the Hartford YWCA. She urged her audience to recognize racism in America as an “urgent” matter that must be resolved by the majority white population. Black people, she said, were “on the move. This is not a threat, but a statement of fact.” The event was recorded and transmitted to Washington by the New Haven office of the FBI, according to a memo in the Robesons’ files, now declassified and available online.

Eslanda was a “Black feminist and also someone whose politics were very much internationalist,” her biographer Barbara Randsby told Amy Goodman on Democracy Now! (February 12, 2013). Her book African Journey (John Day Company)appeared in 1945. She gave street-corner speeches in Hartford’s North End, calling for a federal anti-lynching law, The Courant reported. She became a leader of the Progressive Party in Connecticut and ran for secretary of the state in 1948 and for an at-large seat in the U.S. Congress in 1950. All the while, the FBI was interviewing her neighbors and secretly checking into her activities. She was called in front of Senator Joe McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in July 1953. Paul would appear before HUAC in 1956.

After 1949, large venue promoters refused to book the now-controversial singer. Paul’s supporters secured schools and union halls for his appearances, including on November 15, 1952 at Weaver High School in Hartford. The Courantreported that hundreds of area police were on high alert for the concert, calling it the “greatest mobilization of police in the city’s history.” In the weeks leading up the event The Courant reported opposition to the event, including by a conservative veterans’ groups led by Hartford City Council member John J. Mahon and the local teachers’ union.

Supporting Robeson’s appearance, though, were the local chapter of the American Jewish Congress, Hartford Mayor Joseph Cronin, Republican City Council member Betty Knox, Board of Education President Lewis Fox, civil rights lawyer George Ritter, and school board member Reverend Robert Moody, Hartford’s first Black elected official. The pro-concert officials prevailed. Robeson performed to an auditorium packed with 800 people. The audience called him back for six encores.

By late 1953 the Robesons prepared to leave their Enfield home. Although they had spent more than a decade in Connecticut, they were on the move again, searching for an elusive peace. Their former home, privately owned and not open to the public, is included in the Enfield National Register Historic District and is on the Connecticut Freedom Trail.

Steve Thornton was a vice president of District 1199/SEIU. He maintains the Shoeleather History Project (shoeleatherhistoryproject.com). He last wrote “African American Greats in Connecticut Baseball,” Summer 2018.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Explore!

Read all of our stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SUMMER 2022 CONTENTS