Rocky River power plant powerhouse’s tall windows provide light for monitoring the equipment and accentuate the building’s height. Preservation Connecticut

By Christopher Wigren

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

This story expands on a section of Wigren’s Connecticut Architecture: Stories of 100 Places (Wesleyan University Press, 2018).

In the 20th century humans developed the ability to reshape their environment on an unprecedented scale. New roads bridged valleys and cut through mountains. Reclamation projects turned wetlands into dry ground. Irrigation transformed deserts into farmland and lawns. Mighty rivers were dammed to create reservoirs to satisfy ever-increasing demands for water and electricity.

In about 1900 engineers found that high-tension electrical current could be transmitted for greater distances than had previously seemed possible. Based on this discovery, Connecticut lawyer, businessman, and Republican political boss J. Henry Roraback began acquiring small electric companies in western Connecticut and building a system of reservoirs and power plants to provide power to Connecticut cities. In 1917 he formed the Connecticut Light and Power Company (CL&P), the predecessor of today’s Eversource Energy.

The first installation in what became the consolidated CL&P system, and the first large-scale hydroelectric plant in Connecticut, was the Bull’s Bridge Hydroelectric Plant on the Housatonic River in New Milford, which began operating in 1903, according to the American Society of Engineers. Two more plants followed shortly along the Housatonic: to the north at Falls Village in Canaan, operational in 1914, for the Connecticut Power Company; and to the south at Stevenson (on the Monroe – Oxford town line), in 1919, for CL&P.

Although the Housatonic offered great potential for power generation, seasonal fluctuations made it an unreliable resource. To address this problem, CL&P began planning in 1917 for a fourth hydroelectric plant—but this one would include pumped storage of water in the form of a man-made lake—the future Candlewood Lake. The idea was that water could be pumped into to the lake when the river was high and, when the river was low or demand was high, water could be released from the lake and run back down to turn the turbines and generate power. The new station would be located between the Bull’s Bridge and Stevenson generating stations.

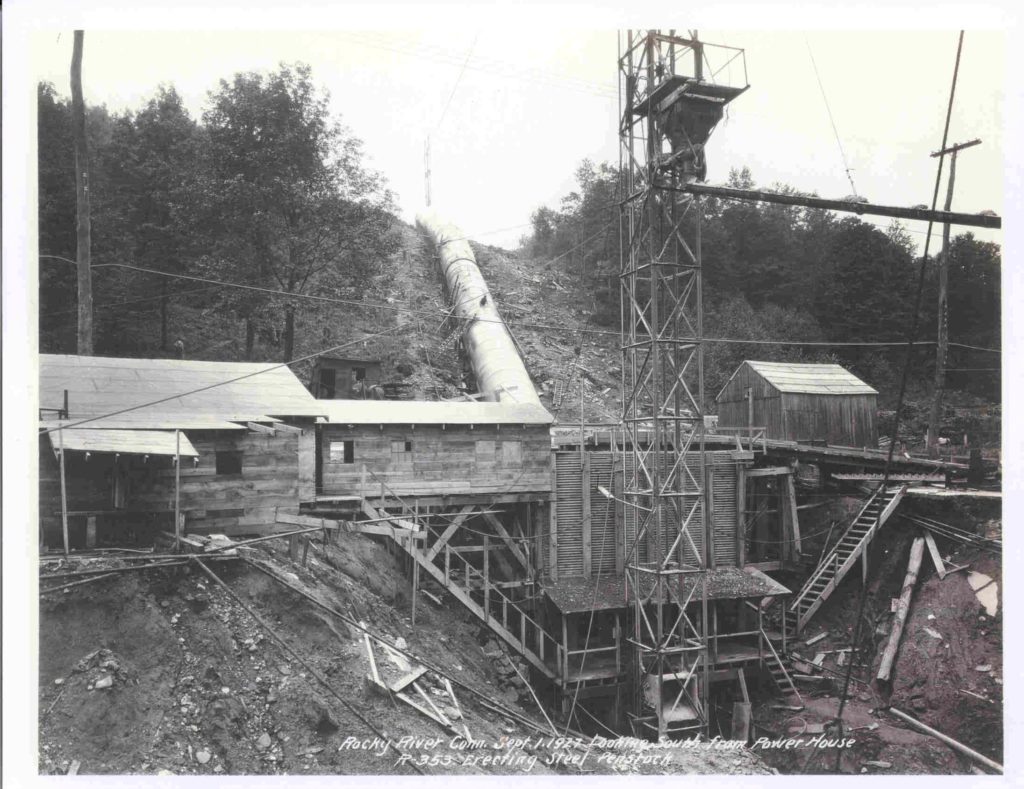

Across Route 7 from the powerhouse, the penstock, seen here during construction in 1927, carries water up to Candlewood Lake. photo: Connecticut Light & Power, courtesy FirstLight Power Resources

In 1926 construction began on a dam across the Rocky River, a tributary of the Housatonic River. The Rocky River Pumped-Storage Hydroelectric Plant opened two years later. It was the first major pumped-storage hydroelectric facility in the United States, which earned it its designation as a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 1980 (available online at asme.org).

Pumping water up actually uses more power than is produced on the return trip, but in addition to ensuring a reliable water supply, the same water continues downstream to the Stevenson Generating Station and, later, to the Shepaug Generating Station (built in 1955). This makes up the energy deficit.

Candlewood Lake (top) with the completed penstock and powerplant (lower left), 1929. Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc.; Western Connecticut State University Archives

Stretching 952 feet long and as much as 100 feet high, the Rocky River dam created Candlewood Lake, 200 feet above the level of the river. The plant employs a penstock system in which giant tubes, 15 feet in diameter, carry water up the hillside to the lake or allow it to flow back down to the power plants when needed. A 76-foot vertical standpipe provides an escape in case of water surges.

The powerhouse, standing between Kent Road and the river, is a lofty brick structure, tall enough to allow the turbines to be lifted out of their housings for servicing. Full-length steel-sash windows provide natural light for monitoring the machinery within and emphasize the building’s height.

The Candlewood Lake Authority’s website notes, “Environmental impact statements were unheard of when the lake was created,” and the environmental impact was massive: behind the dam, more than 8 square miles were flooded in the towns of Danbury, Brookfield, New Fairfield, New Milford, and Sherman, creating a lake 11 miles long, with more than 60 miles of shoreline. CL&P relocated cemeteries and roads and cleared farms, houses, churches, schools—even a village called Jerusalem—not to mention trees and brush. CL&P not only built an electric plant; it created a new landscape many miles long that has attracted development in the form of vacation cottages and year-round homes around the lake.

Candlewood Lake attracted a new mix of plants and animals, fish and birds, forming an ecosystem that in the following decades achieved its own stability. Yet that stability depends on the human-made facility. For as solid as the dam seems to be, it also is fragile. Without ongoing human intervention in the form of maintenance, the water behind the dam, always seeking to run downhill, eventually will break through or flow around it. It will flood the towns downstream, leave lakefront property high and dry, and wipe out the Candlewood ecosystem. It is a useful reminder that whatever people build, they build in opposition to the laws of nature. In the end nature will win out.

Christopher Wigren is deputy director of Preservation Connecticut and the author of Connecticut Architecture: Stories of 100 Places (Wesleyan University Press, 2018) [See “Connecticut Architecture Explored,” Spring 2018].

Explore!

Kids’ Page: “Building Dams for Water & Electricity,” Spring 2020

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

GO TO NEXT STORY

Subscribe to receive every issue!

Sign up for our free bi-weekly e-newsletter