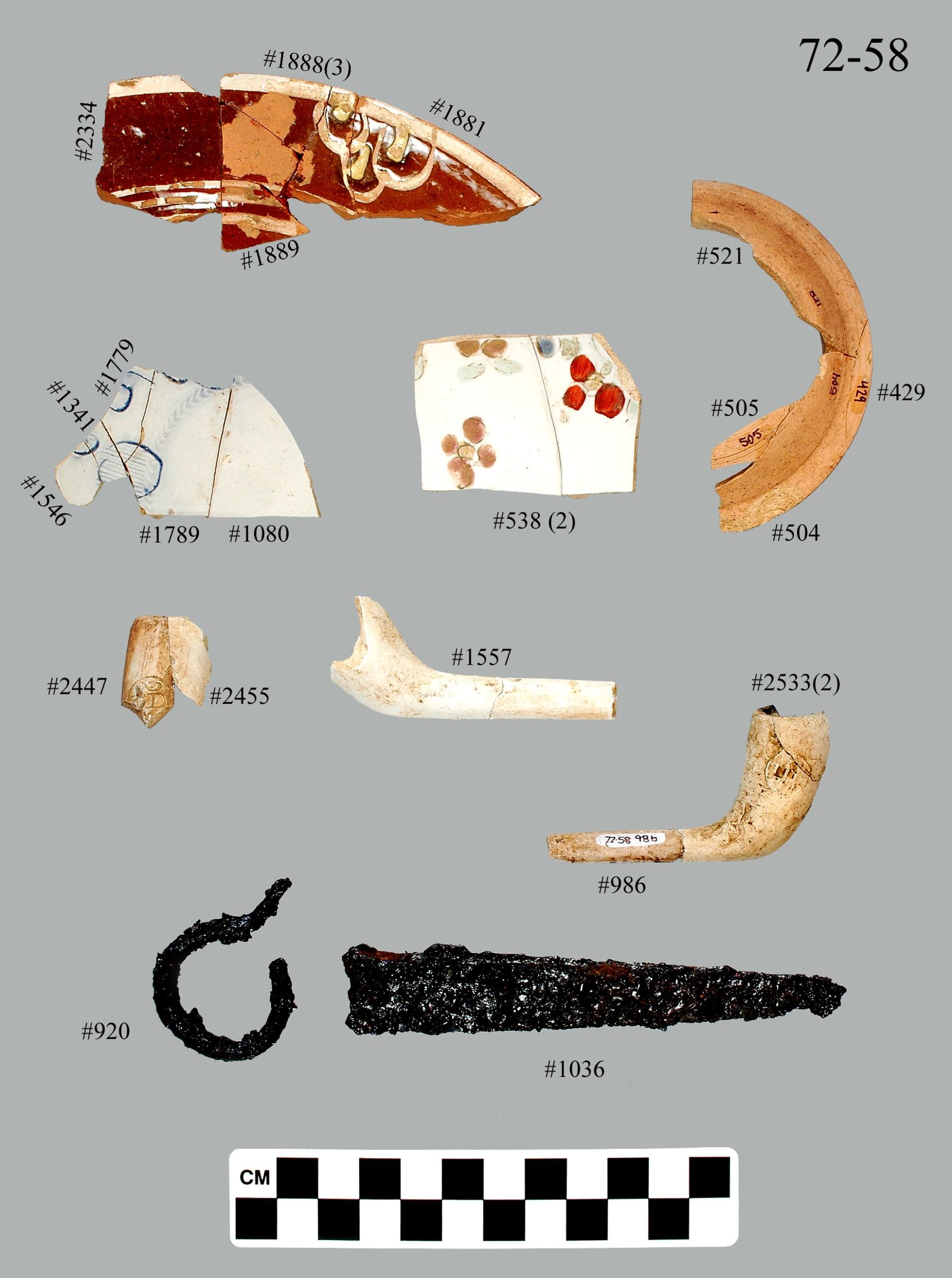

Artifacts from c. 1760 – 1775 unearthed on the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation. Top: English slipware. Second row (l to r): English scratch blue salt glazed stoneware plate, English hand-painted salt glazed stoneware plate, earthenware bowl. Third row: English Kaolin pipes. Fourth row: (l to r) iron jaw harp, iron door hardware. Courtesy the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center

By Kevin A. McBride

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Fall 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The Mashantucket Pequot Reservation in Ledyard is one of the oldest continuously occupied Indigenous landscapes in the eastern United States. Excavations and historical research from 1983 to the present have identified hundreds of pre-Contact and Historic Period Pequot sites. In recognition of its significance, the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation Archaeological District was designated by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior as a National Historic Landmark in 1992. The district comprises 1,245 acres of federal trust lands (the Mashantucket Pequot gained federal recognition in 1983) and 392 acres held by the tribe in fee simple. Robert Grumet and I discuss this history in “The Mashantucket Pequot Indian Archaeological District: A National Historic Landmark,” Bulletin of the Archaeological Society of Connecticut (vol. 59, 1996). Archaeological evidence reveals both change and continuity in the Mashantucket Pequot way of life over 300 years.

For thousands of years the 500-acre Great Cedar Swamp, located in the middle of the reservation, was a focal point of pre-Contact occupation and land use. Evidence reveals hundreds of occupations dating from the Paleo-Indian through the early Contact Period along the margins of the swamp. Pequot place names associated with the swamp include “Cuppahommock” (place of refuge) and “Ohomowauke” (Owl’s Nest) and testify to the site’s spiritual and cultural importance to the Pequot people, as I document in “The Historical Archaeology of the Mashantucket Pequot” in The Pequots in Southern New England: The Fall and Rise of an American Indian Nation (University of Oklahoma Press, 1990).

Map showing the location of the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation. The Great Cedar Swamp is shown as the large green area in the upper right; Monhantic Fort site is southeast of the swamp. Courtesy of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center

The reservation was established in 1666, one of the earliest reservations in the United States. At the end of the Pequot War of 1636 – 1637, the Mashantucket band of Pequots was one of many small groups of Pequot survivors scattered throughout southern New England. In 1638 they numbered around 400 to 500 individuals residing in five villages at Nameag (New London). Between 1650 and 1678 the Connecticut Colony allowed the Mashantucket Pequots to use several different tracts of land on the east side of the Thames River, including Noank (500 acres) and Mashantucket (“great wooded place” – 2,500 acres). These lands included a wide range of coastal, estuarine, woodland, and wetland habitats that enabled the Mashantucket Pequots to pursue a traditional mixed economy of maize horticulture, hunting, gathering, and fishing.

Monhantic Fort is one of the more significant sites on the reservation and the most archaeologically intact Native palisade and village in the region, as I documented for the Suffolk County Archaeological Association’s Readings in Long Island Sound Archaeology and History (2007). The fortified village of approximately 250 people was constructed during King Philip’s War and abandoned around 1678. Within its walls are dozens of wigwams, storage and refuse pits, and a wide range of Indigenous and European artifacts and food remains that tell us a great deal about the impact of European settlers on Pequot lifeways in this period.

As the Colonial population grew in the early 18th century, farmers encroached on Pequot land, resulting in the loss of 75 percent (2,500 acres) of the Mashantucket Pequot’s land base during a 20- to 30-year period. This caused, as I document in “Transformation by Degree: Eighteenth Century Native American Land Use at Mashantucket” in Eighteenth Century Native Communities of Southern New England in the Colonial Context (Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center, 2005), significant changes in the Mashantucket subsistence economy as the Pequot adapted and worked to maintain themselves on their homeland.

During the middle decades of the 18th century, the documentary record appears to reflect a radical cultural transformation, with changes in ideology, architecture, land use, and foodways. In the 20 years between 1740 and 1760, many of the Mashantucket Pequots converted to Christianity, constructed English-style framed houses, and adopted Euro-American farming techniques and European domesticated animals. The remains of late 18th- and early 19th-century house and barn foundations, root cellars, and fields bounded by dry-laid stone walls attest to the physical transformation of the Mashantucket landscape.

To the casual observer it would appear that 150 years of effort by English missionaries and the Connecticut colonial government to Christianize and Europeanize the Mashantucket Pequots had succeeded. Contrary to the documentary record, though, the archaeological record reflects a high degree of continuity in Pequot subsistence patterns, particularly in the use of indigenous plants and traditional maize horticulture. The adoption and integration of European domesticated plants and animals was a highly selective process. Any attempt to explain the transformation of the Mashantucket cultural landscape must consider a variety of factors, including the individual responses of families and communities to the economic, political, and social events of the 18th century. Throughout, the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation has remained a vital homeland for the members of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation.

Kevin McBride is an associate professor in the anthropology department at University of Connecticut, Storrs. He last co-wrote, “Connecticut’s Contested Early 17th-Century Landscape,” Summer 2019.

Kevin McBride is an associate professor in the anthropology department at University of Connecticut, Storrs. He last co-wrote, “Connecticut’s Contested Early 17th-Century Landscape,” Summer 2019.

Explore!

Read all of our stories about the Native American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO FALL 2022 CONTENTS