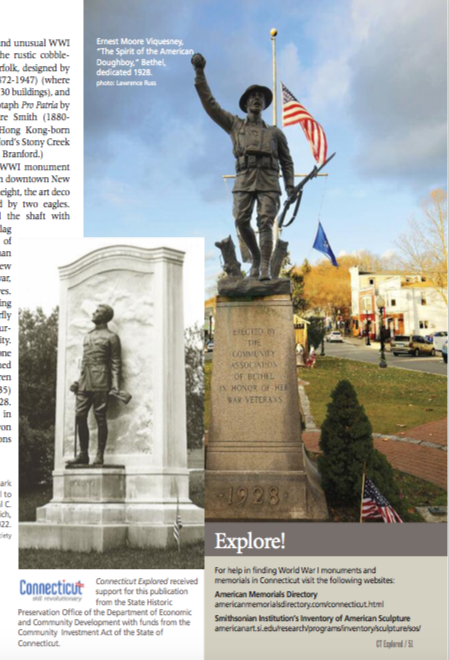

Ernest Moore Viquesney, “The Spirit of the American Doughboy,” Bethel, dedicated 1928. photo: Lawrence Russ. Inset: Edward Clark Potter, Memorial to Col. Raynal C. Bolling, Greenwich, dedicated 1922. Greenwich Historical Society

By Mary M. Donohue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2017

Subscribe/Buy the Issue

When most people today hear the word “doughboy,” an image of the Pillsbury Company’s “Poppin’ Fresh” doughboy probably comes to mind rather than the American soldiers of World War I. The origin of the term “doughboy” is murky, but the image defined World War I’s troops in the same way “the Hiker” did for the Spanish-American War and “G.I. Joe” did for World War II.

After the tremendous losses of the Civil War, Americans embraced war memorials and monuments on a massive scale. [See “Memorials to a Nation Preserved,” Connecticut Explored, Spring 2011.] During the 18 months of U.S. involvement in WWI, two million American men served and 50,000 died. Americans were by then accustomed to erecting significant public monuments. In addition to the classic war memorial featuring a figure on a tall base, WWI monuments in Connecticut include a wide range of designs from simple cast-metal plaques to flag poles, commemorative bells, and innovative landscape designs such as Hartford’s now-lost “Trees of Honor” memorial in Colt Park that featured 213 elm trees to honor those who died. [“Restoring Hartford’s Lost WWI Memorial,” Summer 2015.]

Two Connecticut monuments that feature the emblematic Doughboy are the work of sculptor and persuasive salesman Ernest Moore Viquesney (1876-1946), a third-generation stone carver. Viquesney developed a now-iconic design he called “The Spirit of the American Doughboy.” A veteran of the Spanish American War, Visquesney was employed at two monument companies in Americus, Georgia and claimed to have worked with Gutzon Borglum of Mount Rushmore fame while Borglum was working on his Stone Mountain project.

According to the E. M. Viquesney Doughboy Database (doughboysearcher.weebly.com managed by Les Kopel), Viquesney created “The Spirit of the American Doughboy” in 1920. The design depicted a “Doughboy striding firmly forward in an erect posture through ‘no man’s land’… He wears a flat steel helmet, trousers bloused above the knee, and puttees (wrapped leggings).” The figure holds a 1903 Springfield rifle in one hand and a grenade in his upraised right hand, with barbed wire strung loosely around his feet. Viquesney copyrighted the design and sold it across the country from his factory in Spencer, Indiana. Miniature versions and lamps were recommended by Viquesney for local fundraising efforts to inspire donors to make substantial donations. Donors that contributed at a predetermined amount would receive a lamp from the local committee, with Viquesney selling them to the committee at wholesale price. Viquesney sent fundraising kits out to communities across the country.

Connecticut’s two verified “Spirit” sculptures are found in Bethel and North Canaan. According to the Viquesney Doughboy Database, the Bethel monument was chosen after a local resident displayed the lamp version at a community meeting. The town voted to purchase a copper version of the Doughboy from Viquesney, and it was dedicated on May 30, 1928. It was restored in 2016. The “Spirit of the American Doughboy” could be ordered in three different materials: pressed copper, stone, or cast zinc. Both of the Connecticut examples are of pressed copper.

The town of North Canaan’s “Spirit” Doughboy rests atop a bell-shaped, rustic, cobblestone base surrounded by low cobblestone walls as part of a town monument to men who served in all wars through WWII. The town elected to purchase a Viquesney Doughboy to complete the composition in 1928. Other towns that have monuments that include a Doughboy figure of other than Viquesney’s design include East Hartford, New Haven, and Westport.

In Greenwich, a memorial to Colonel Raynal C. Bolling (1877-1918) commemorates the man credited as founding father of the modern U.S. Air Force. Bolling, assistant chief of the Air Service, was the first high-ranking air service officer killed in WWI.

The sculpture’s bronze figure shows Bolling scanning the sky. The stele behind him has a relief of two planes among the clouds. The memorial was designed by New London-born Edward Clark Potter (1857-1923), who lived in Greenwich and summered in New London and is best known for creating the marble lions in front of New York Public Library.

Connecticut’s foremost female sculptor of the time, Evelyn Beatrice Longman Batchelder (1874-1954), a longtime resident of Windsor, designed the sepulchral monument on the Naugatuck town green. The pink granite base is carved with classical symbols of peace. Rams heads represent those who have died in war. The poignant text reads in part, “In honor of the great men of Naugatuck who gave their lives in the Great War for the chaining of savagery and the liberation of a manacled world.” Longman was the first woman to be granted full membership in the National Academy of Design in New York.

Other outstanding and unusual WWI monuments include the rustic cobblestone bell tower in Norfolk, designed by Alfredo S.G. Taylor (1872-1947) (where he designed more than 30 buildings), and the blocky granite cenotaph Pro Patria by WWI veteran J. Andre Smith (1880-1959) in Branford. (Hong Kong-born Smith grew up in Branford’s Stony Creek section and is buried in Branford.)

The state’s largest WWI monument is in Walnut Hill Park in downtown New Britain. Ninety feet in height, the art deco obelisk is surmounted by two eagles. A flag wraps around the shaft with 12 drapes of the flag serving as the fluting of the column. More than 4,000 residents of New Britain served in the war, and 123 lost their lives. Large, urn-shaped lighting fixtures feature a butterfly motif symbolizing resurrection and immortality. The granite-and-limestone monument was designed by Harold Van Buren Magonigle (1867-1935) and dedicated in 1928. Magonigle specialized in monuments and won important commissions across the country.

The state’s largest WWI monument is in Walnut Hill Park in downtown New Britain. Ninety feet in height, the art deco obelisk is surmounted by two eagles. A flag wraps around the shaft with 12 drapes of the flag serving as the fluting of the column. More than 4,000 residents of New Britain served in the war, and 123 lost their lives. Large, urn-shaped lighting fixtures feature a butterfly motif symbolizing resurrection and immortality. The granite-and-limestone monument was designed by Harold Van Buren Magonigle (1867-1935) and dedicated in 1928. Magonigle specialized in monuments and won important commissions across the country.

Mary M. Donohue is an architectural historian and the assistant publisher of Connecticut Explored.

Explore!

For help in finding World War I monuments and memorials in Connecticut visit the following websites:

American Memorial Directory

americanmemorialsdirectory.com/connecticut.html

Smithsonian Institution’s Inventory of American Sculpture

americanart.si.edu/research/programs/inventory/sculpture/

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.