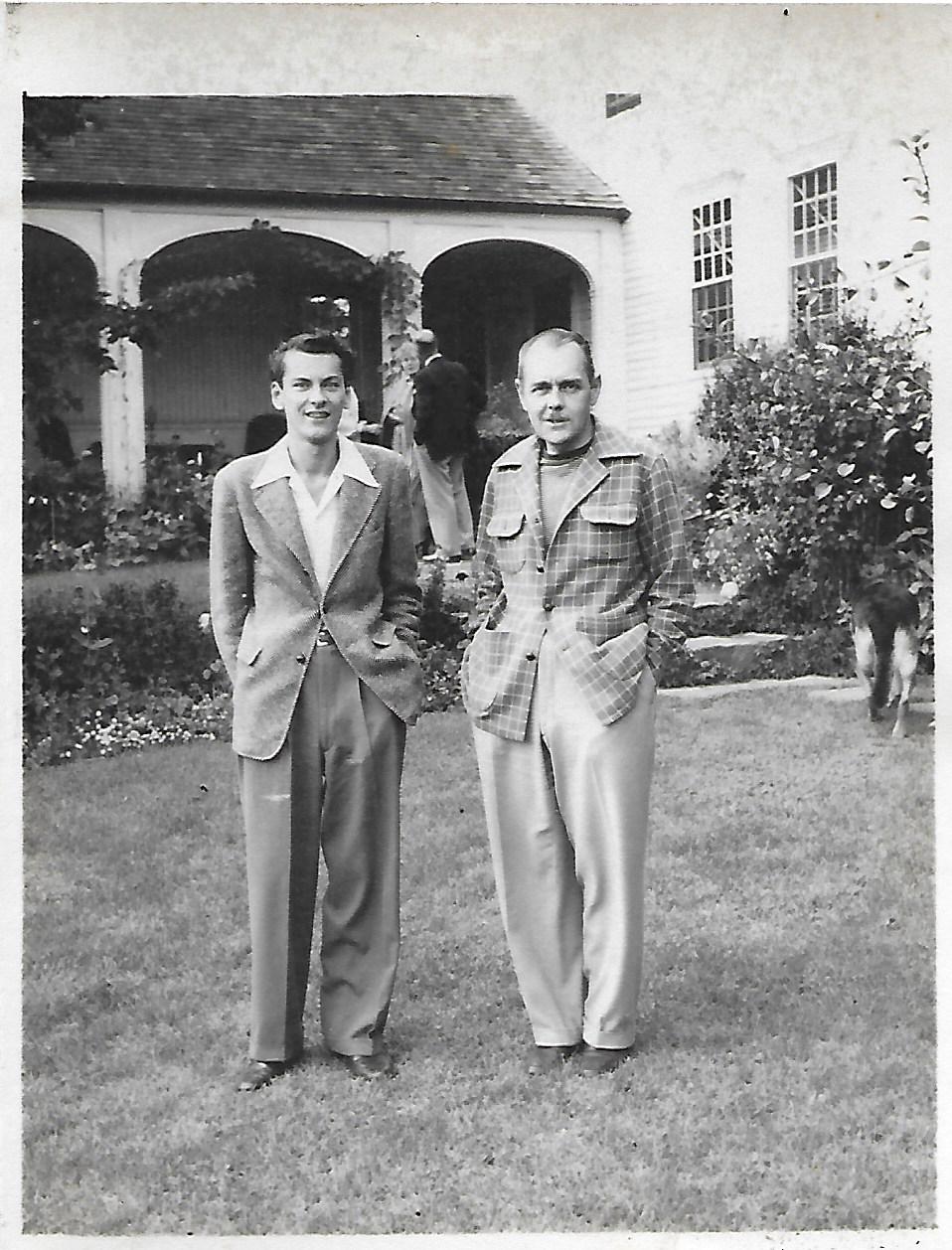

Howard Metzger (left) and Frederic Palmer at their home, now the Palmer Warner House, c. 1945. Connecticut Landmarks

By Erin Farley

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2019

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

As the 50th anniversaries of the Stonewall Uprising and the first Pride rally are commemorated this year, one museum is preparing to tell its LGBTQ history.

Historic house museums have long focused on the stories of traditional, heterosexual, nuclear families. But one non-traditional family story will soon be told at the Palmer-Warner House in East Haddam, Connecticut. The house, built in 1738, is the most recent acquisition of Connecticut Landmarks (CTL), a statewide network of 11 significant historic properties that span four centuries of Connecticut history. Frederic Palmer bequeathed it to CTL in 1948 with the stipulation that his partner, Howard Metzger, be given life tenancy. Connecticut Landmarks is preparing the property to be opened to the public in 2021.

Like most historic house museums, the 281-year-old Palmer-Warner House can tell many stories, including that of the Warners, the colonial blacksmithing family that built it in 1738. The site includes significant examples of an 18th-century center chimney house and barn.

Now the story of its last residents will also get attention. That story began when preservation architect Frederic Palmer and his mother Mary Brennan Palmer purchased the property in 1936 and moved in. Frederic was born in 1901 to a manufacturing family in Montville. He received a master’s degree in architecture from Harvard University in 1931 and worked in historic preservation. East Haddam’s First Congregational Church and the Goodspeed Opera House were two of his projects. He was a trustee of the Antiquarian & Landmarks Society (A&LS, now CTL) and chaired the society’s structures committee from 1944 to 1971. In that role, he was instrumental in preserving many of CTL’s properties.

Palmer did extensive work on his East Haddam house. He and Metzger filled it with antiques—to such great effect that the house was featured in Antiques Magazine in 1957. In making modifications, Palmer balanced the house’s historical significance with its modern use, always with the intention of preserving it for future generations. “It is not my purpose to leave a museum furnished as an example of life in the 18th century,” he wrote in a letter to A&LS director John Holcombe Jr. dated May 7, 1948, “but rather a [sic] 18th century house as lived in and used by a gentleman in the middle of the 20th century.”

Two years after Mary Palmer’s death in 1943, Palmer met Metzger through mutual friend Jack Pierce, a stage actor in New York City. Metzger was born in Ohio in 1921 and served in the U.S. Merchant Marine during World War II. By June of that year, Metzger, when not at sea, had joined Pierce as a roommate in Palmer’s East Haddam house. This can be viewed as the start of Palmer’s providing a safe place for his gay friends to gather. Since the 1930s society’s attitudes had become more anti-gay, notes The New York Times in “A Gay World, Vibrant and Forgotten,” (June 26, 1994). Between 1923 and 1967, in New York City alone, 50,000 people were arrested under anti-homosexuality laws. “Threatened with police raids, harassment and the loss of their jobs, families and reputations,” The Times noted, “most people hid their participation in gay life.”

Palmer and Metzger’s relationship grew, as Palmer’s diaries and letters reveal. These letters, now in CTL’s archives, are powerful and show the depth of their relationship and its evolution over time. Between 1945 and 1948 Palmer wrote hundreds of letters—one nearly every day—to Metzger, who was still working for the merchant marine. These letters, which I am currently analyzing, inform an understanding of the two men and their relationship that would otherwise have been lost if they had not been preserved.

While Metzger was at sea, where letters were read by censors, Palmer wrote mostly about daily life. Metzger scolded Palmer on a few occasions, though, about getting too personal. In response to one scolding, Palmer wrote, on July 10, 1945, “Gosh I wish I could write some [sic] few of the things I really want to say BUT. It would be such a relief to be able to let go, and get some of it off my mind.” Palmer expressed annoyance at being watched. “Of course it is more fun for you to be up here, and for me,” he wrote to Metzger August 26, “than for me to be in town with a million people watching us all the time.”

When Metzger was on land, usually in New York City awaiting another assignment, the two were free to air their true feelings for one another. In a letter dated December 19, 1945, Palmer wrote that he was “The one person who’s [sic] love and devotion [Metzger could] count on until the end of time.”

When Metzger was on land, usually in New York City awaiting another assignment, the two were free to air their true feelings for one another. In a letter dated December 19, 1945, Palmer wrote that he was “The one person who’s [sic] love and devotion [Metzger could] count on until the end of time.”

It is unusual for a historic property to be gifted to a museum organization with a well-documented LGBTQ story complete with letters and diaries that provide so much context and depth. Evidence of same-sex relationships often has been destroyed by family members before they donate a home to be operated as a museum, as was the case with Beauport, Henry David Sleeper’s home in Gloucester, Massachusetts. The Palmer-Warner property gives us an exceptional opportunity to tell an important, under-represented American story.

For more information about the Palmer-Warner House, visit ctlandmarks.org.

Erin Farley is collections manager and Palmer-Warner project manager for Connecticut Landmarks.

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.