By Ramin Ganeshram, Nicole Carpenter, and Sara Krasne

By Ramin Ganeshram, Nicole Carpenter, and Sara Krasne

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

On New Year’s Day 1935, reporter Sigrid Schultz witnessed raucous celebrations in Germany’s Black Forest. Shooting rifles into the air, the members of the fast-rising National Socialist (Nazi) Party celebrated their leader, Adolf Hitler, and his rising hegemony over the German political landscape. Schultz reported the incident via telegram to her editor at The Chicago Tribune, writing, “… year two of Hitler’s Fuehrer Germany finds Germany comparable to a mass of cooling lava after a volcano eruption with some people getting burned and nobody certain where the lava will finally settle… .”

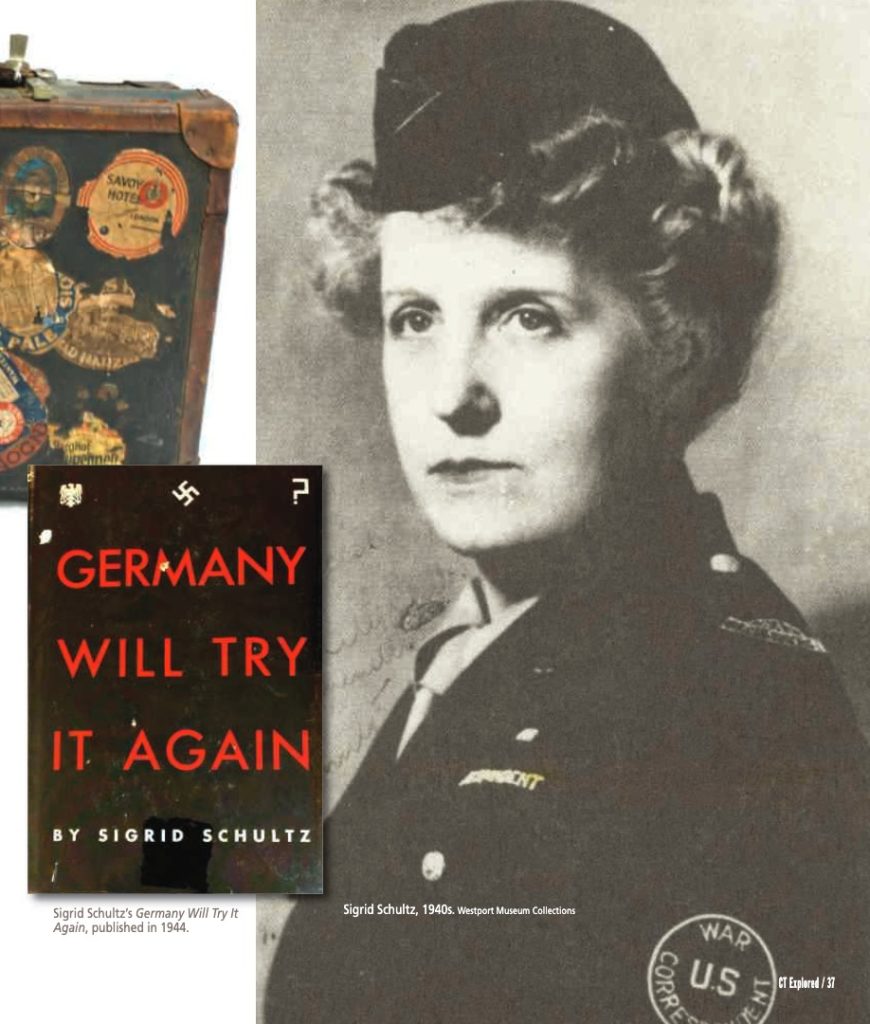

Schultz, an American from Chicago who later settled in Westport, Connecticut and who is now celebrated in a special exhibition on view through June 2021 at the Westport Museum, had been the Tribune’s Berlin bureau chief for nearly 10 years by that time. She may have been the first woman to hold that post in a major American news organization. Her position gained her access to Hermann Göring, the man who would be Hitler’s second in command, and from this position, she was able to report to—and forewarn—American readers about the Third Reich’s insatiable hunger for power and unquenchable thirst for violence. She’d come a long way from her Chicago beginnings as the privileged daughter of a celebrated portrait painter.

According to passport applications, in summer 1892 Herman Schultz, a Norwegian artist, and his Austrian-German wife Hedwig, an opera singer, arrived in the United States. While in Chicago, Herman received commissions from luminaries such as Mayor Carter Harrison, and his success allowed the couple to settle in a large house in the Summerdale section of the city. Hedwig gave birth to their daughter Sigrid in January 1893. Sigrid was their only child.

Sigrid attended the Ravenswood School while her father continued to paint portraits. In her private writings and authorized biographical interviews, Sigrid spoke of an idyllic childhood. A cache of glass-plate negatives, found in Sigrid’s childhood home in 2020 just before it was demolished, depicts the interior of the family’s comfortable home and the presence of their St. Bernard dogs. Sigrid was exposed to Chicago’s artists, politicians, and intelligentsia at the family’s frequent parties for friends.

By the turn of the century Herman’s reputation as a portraitist was known in transatlantic circles, and the family moved to Germany when Sigrid was eight years old. Herman received commissions from various German aristocrats. His career took the family on frequent travels around the continent and to Cairo, where Herman had a studio. In 1902 Sigrid and her mother settled in Paris, where Sigrid studied at the Lycée Racine before moving on to the Sorbonne University to study international law.

In 1913, due to “the weakness of lungs,” Sigrid was sent to Switzerland for treatment at a sanitarium in Lucerne. After spending some months there, she moved with her mother to Berlin, Germany, where Sigrid studied the German language. Though they were living abroad, her parents became naturalized United States citizens in 1914. With her parents’ health in decline by the time the first World War began, travel to the United States was impossible. Reunited with Herman, the family remained in Germany.

But young Sigrid, now in her 20s, had proven quite proficient at languages. Speaking English, French, and German (her mother’s native language), she worked as a language teacher in Berlin during World War I, tutoring French and English to private clients before being hired as a translator at the Turkish embassy. Teaching allowed Sigrid to sustain her family during the war despite scrutiny. Later, Sigrid would describe the difficulty of life as ex-patriates in Germany where they were considered enemy aliens requiring police check-ins twice a day.

In 1919, when The Chicago Tribune sought an interpreter fluent in both English and German to translate for correspondent Richard Henry Little, Sigrid got the job. Known for his interviewing skills, Little taught Schultz how to make interviewees feel comfortable, using humor and social events to provide introductions and conversation. “Let the facts speak for themselves,” was another lesson Schultz attributed to Little, as noted in her personal papers at Westport Museum.

The Tribune owner “Colonel” Robert Rutherford McCormick refused to appoint women to news-reporting positions. Through humor, intelligence, cleverness, and strong reporting, though, Schultz was able to break through his notoriously biased system, she said in an oral memoir recorded by The American Jewish Committee in 1971. She noted that in 1925 McCormick was so impressed by her undercover reporting on the impending death of Friedrich Ebert, the first president of the Weimar Republic, that he promoted her to the “number two man” in the Berlin office. In 1926 Schultz became the paper’s chief of the Berlin bureau—the first woman to hold that position for a major American news service and a position she held until 1941, according to Schultz’s papers at the Westport Museum.

With the rise of Hitler’s Nazi party, Schultz’s job became more dangerous. While she saw clear evidence of Hitler’s evil intentions for war and Jewish extermination, she had to remain impersonal in order to maintain her position of access—especially after other Allied journalists had been expelled from Germany in 1932. Taking extreme risks, Schultz filed her most explosive and revealing reports under a pseudonym, John Dickson, while traveling outside of Germany. Göring came to suspect Schultz by 1936, she said in her oral memoir, and was enraged by her reporting, calling her “that dragon from Chicago.” He had several attempts made on her life, yet she outsmarted him every time, according to her papers at Westport Museum.

Schultz was forced to leave Germany in 1941 after being injured while reporting during an Allied air raid. She recuperated in Spain but came to Westport in late 1941. By that time, her father had been dead for 15 years. She had intended to settle in Washington, D.C., but her mother had seen what she called “a crazy little house in the middle of Westport” during a Christmas-time visit to a friend in Weston in 1939. She and her mother purchased the house, and Westport remained Sigrid’s home town over the course of the next 40 years.

On October 27, 1941, The Chicago Tribune ran a full-page ad encouraging women to subscribe by highlighting 28 female correspondents. Schultz is the only one listed as a serious news journalist. It was well known and remarkable that she, an American woman, had for a time gained entrée into the inner sanctum of the Nazi Party.

Schultz attempted to re-enter Germany and resume her reporting from 1941 to 1944, but her visa requests were denied. Instead, from her home in Westport, she tirelessly worked toward defeating the Nazi threat, including by writing Germany Will Try It Again (Reynal & Hitchcock, 1944). The book outlined the lead-up to World War I, contemporary events during the last stage of World War II, and Schultz’s concerns that Germany would again rearm and begin World War III.

As her papers at the museum and oral memoir attest, Schultz was deeply involved in providing the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) important intelligence she had gathered while reporting on the Nazis from within Germany. The OSS later became the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which depended on in-country spies for information about important targets. Relying on memory and the prodigious notes she had taken as a reporter, Schultz was able to provide the OSS with hundreds of pages of detailed dossiers about key Nazi figures both in Germany and in the United States, such as Adolf Hitler’s girlfriend and eventual wife Eva Braun, George Sylvester Viereck, an American citizen and Nazi propagandist, and Philipp Bouhler, chief of the chancellery of the führer of the Nazi Party and overseer of the involuntary euthanasia of “uncurables” in Germany—intelligence that aided the war effort and, later, brought these war criminals to justice.

As her papers at the museum and oral memoir attest, Schultz was deeply involved in providing the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) important intelligence she had gathered while reporting on the Nazis from within Germany. The OSS later became the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which depended on in-country spies for information about important targets. Relying on memory and the prodigious notes she had taken as a reporter, Schultz was able to provide the OSS with hundreds of pages of detailed dossiers about key Nazi figures both in Germany and in the United States, such as Adolf Hitler’s girlfriend and eventual wife Eva Braun, George Sylvester Viereck, an American citizen and Nazi propagandist, and Philipp Bouhler, chief of the chancellery of the führer of the Nazi Party and overseer of the involuntary euthanasia of “uncurables” in Germany—intelligence that aided the war effort and, later, brought these war criminals to justice.

Schultz returned to Europe in January 1945 as a war correspondent for the Tribune, McCall’s magazine, and Mutual Broadcasting, accompanying the First Army as it advanced into Germany with Allied troops from Belgium. She was one of the first journalists at the liberation of Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Speaking about what she witnessed there in her oral memoir, Schultz described entering the camp office: “On that table of the officer there was a lamp made of…[what]looked as if [it]were parchment … and it was built on what looked like bones. Well it turned out those were human things … made of human skin … that the wife of the commander of the Buchenwald Concentration Camp had had made for her entertainment.”

At Buchenwald Schultz met prisoners who, despite being liberated, would not survive. She described them in detail in her oral memoir. “This Frenchman … who had been [used as a horse in the mines]told me, ‘If you have the courage, there is a hospital in the back there and there are mostly Frenchmen in there and a few Poles and they are dying. Your American Doctors … will not be able to save them. It would be good if they heard somebody speak French to them and tell them that they are free, especially your woman’s voice … . One man sat up … and said ‘Is it really true?’ And I said ‘It’s really true, you are free’ and he was gone.”

Schultz was among the few reporters admitted to the Luneburg trials of Nazi concentration camp officials at Bergen-Belsen. She recalled in 1971: “The British ran that trial with wonderful dignity and extreme fairness. But it was incredible to see the absolute ruthlessness of some of those guards on trial… . You’d have those vile women … there were men and women … 45 accused with [Josef] Kramer, the Beast of Belsen.”

Schultz returned to the U.S. in December 1945 and continued to tirelessly write for the next 40 years about anti-Semitism and the dangers of national extremism. Schultz was well known throughout Westport and was a woman of many talents—including as the writer and editor of a number of international cookbooks.

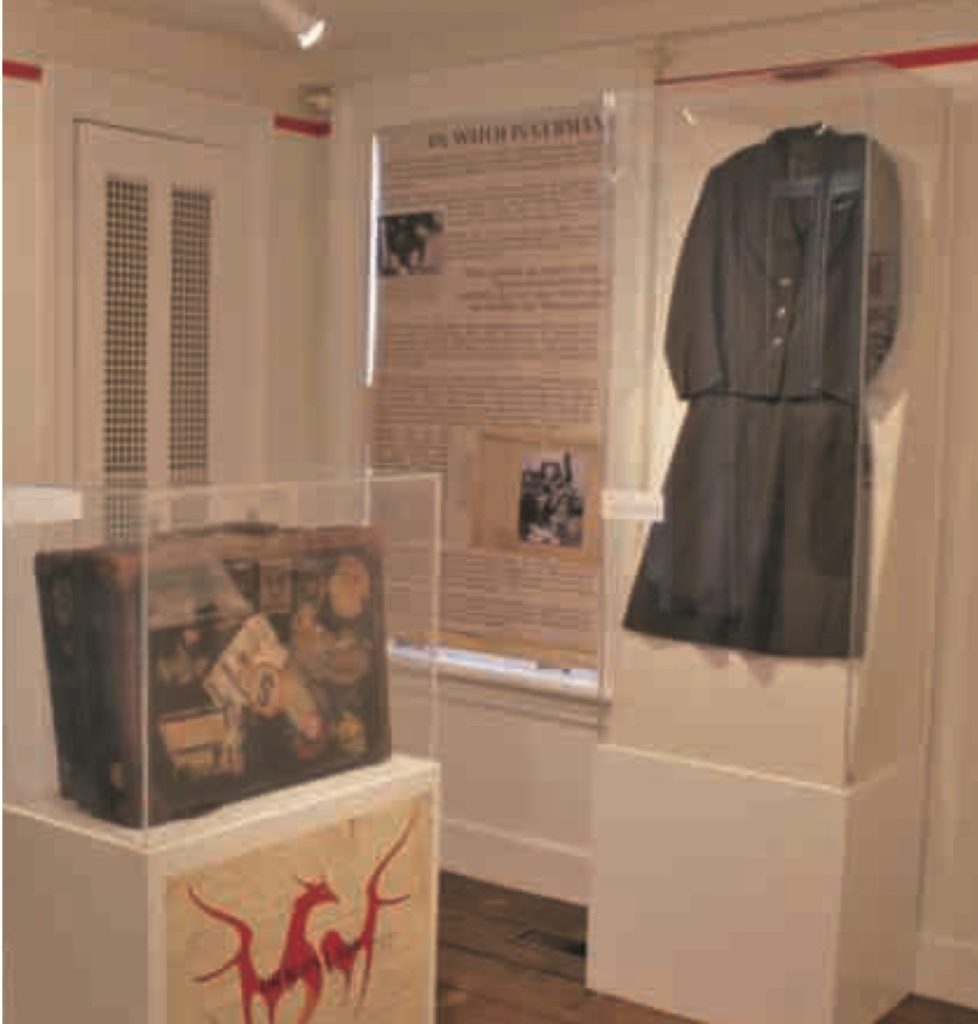

Sigrid Schultz died in 1980, after which she seems to have been largely forgotten. Even staff at the Westport Museum only knew of her in passing until, by chance, her battered suitcase was discovered in the museum’s attic—a misplaced collection item—while staff members were searching for a prop for an exhibit. Covered in transit stickers, including one from the Third Reich, the suitcase inspired us to look at our collections’ database to determine to whom it belonged. That discovery led us down a path of exploring the life of this remarkable woman who had, in fact, left even more of her memorabilia to the museum at her death in 1980. Today all of Schultz’s donated items have been rehoused in proper collections storage as part of a larger newly instituted museum-wide collections management plan.

In the hopes of having someone publish her biography, Schultz worked with Cynthia Chapman, a doctoral candidate at the Florida Institute of Technology, and even created a trust to publish the completed biography at a future date. While that biography was ultimately not written (although Dr. David Milne at the University of East Anglia is currently writing one), a secondary use for the endowment as set by Schultz was to support journalism students who hoped to go into international reporting.

The scholarship, which is administered by Central Connecticut State University, has allowed undergraduates studying journalism to travel to Europe to walk in Sigrid’s shoes. Sadly, a May 2020 trip to follow Schultz’s journey during the liberation of Buchenwald was canceled due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Were she alive today, one wonders how Schultz, a fearless investigator, would be reporting on Covid-19, economic depression, or racial inequity in America—all stories of international importance. Surely she would have been on the front lines.

Less than a year after Schultz’s death, her Westport home at 35 Elm Street was bulldozed to make way for a public parking lot. More than a decade earlier, she had convinced the town to buy her property for public use but allow her to live there until her death, ultimately delaying the project, of which she disapproved for many years, according to contemporary articles in The Westport Town Crier and The Westport News.

In 2019 the Town of Westport approved plans to place a commemorative plaque at the site of Schultz’s home. Yet, even in this the reporter courts controversy from the grave as a group of amateur historians and genealogists have claimed to find proof that Schultz was, in fact, Jewish. Their hope is that the commemorative plaque would indicate this. The claim of Sigrid Schultz’s Jewish roots is based on a single ship’s manifest from a vessel transporting Jewish refugees from Europe in 1936. Schultz had sent her mother back to America, and Hedwig is listed among the “Hebrew” passengers, with a ditto mark next to her name in the column indicating ethnicity. While tantalizing, it is a lone document among plentiful evidence amassed by Schultz scholars who feel the ditto mark was likely no more than an error by ship’s crew members and overlooked by immigration officers. Sigrid never discussed a Jewish identity—despite being clear and painstaking about her heritage and the correct reporting of it, as indicated in her acerbic 1967 letter to Associated Press reporter Louis Lochner taking her colleague to task for getting the facts of her ethnicity wrong—claiming that she was German and simultaneously hated German culture.

The remarkable life of Sigrid Schultz is celebrated in Westport Museum’s exhibition DRAGON LADY: The Life of Sigrid Schultz, will be on view into 2021 once Westport Museum reopens. The museum is preparing a Facebook Live virtual tour of the exhibition which will also be available in recorded form on the museum site and Facebook page. Visit virtualhistorywestport.org for programming related to the exhibition.

DRAGON LADY: The Life of Sigrid Schultz, on view at Westport Historical Society through June 2021. Westport Historical Society

Ramin Ganeshram is executive director of Westport Museum for History and Culture. She last co-wrote “Black Suffrage: Rights for All?,” Fall 2018. Nicole Carpenter is programs and education director, and Sara Krasne is archives manager at Westport Museum for History and Culture.

Explore!

DRAGON LADY: The Life of Sigrid Schultz

On view through June 2021

Westport Museum for History and Culture

25 Avery Place, Westport

westporthistory.org; 203-222-1424

Read more about Connecticut in World War II in our Fall 2020 issues, and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page. Read more about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page.