Sun and Sea Harnessed to Fight Tuberculosis

The history of Seaside

By Ann Harrison with Mark Jones

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

“The ideal places for treatment of these cases are mountain tops above the cloud lines, and ocean beaches. Connecticut has no mountain tops above the cloud lines, but she has more than a hundred miles of ocean beach.”

Such was the argument made by the Connecticut State Tuberculosis Commission in a 1912 report titled “Why Connecticut Should Have a Seaside Sanatorium.”

The General Assembly first heeded the pleas of doctors to address tuberculosis on a state level in 1907. It took years of success in Europe of seaside sanitoria before Connecticut invested in the idea. Connecticut made its first appropriation toward fighting the tubercle bacillus in 1910. At the time, tuberculosis killed 252 of every 100,000 people living in the state, making it the leading killer in the state early in the century. After it came cancer and heart disease, which followed with their own specialty hospitals.

By 1934, thanks largely to state intervention and better knowledge of the safe handling of food, tuberculosis killed fewer than 50 of every 100,000. While this rate was favorable compared to adjoining states, it still meant that “about one funeral out of 20 in Connecticut [was]caused by the tubercle bacillus,” according to a 1934 report of the State Tuberculosis Commission.

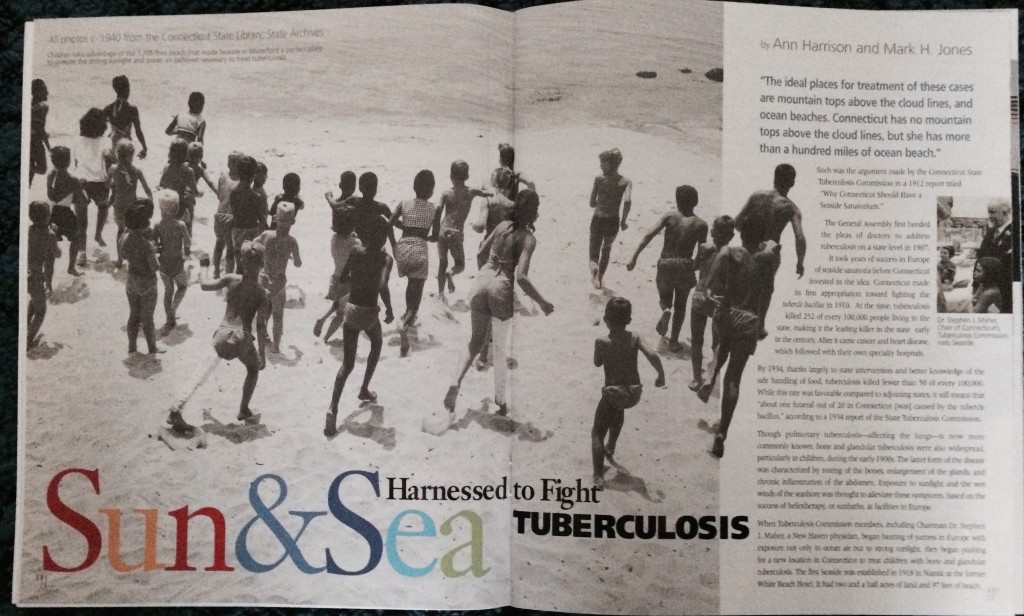

Though pulmonary tuberculosis—affecting the lungs—is now more commonly known, bone and glandular tuberculosis were also widespread, particularly among children, during the early 1900s. The latter form of the disease was characterized by rotting of the bones, enlargement of the glands, and chronic inflammation of the abdomen. Exposure to sunlight and the wet winds of the seashore was thought to alleviate these symptoms, based on the success of heliotherapy, or sunbaths, at facilities in Europe.

When Tuberculosis Commission members, including Chairman Dr. Stephen J. Maher, a New Haven physician, began hearing of success in Europe with exposure not only to ocean air but to strong sunlight, they began pushing for a new location in Connecticut to treat children with bone and glandular tuberculosis. The first Seaside was established in Niantic in 1918 in Niantic at the former White Beach Hotel. It had two and a half acres of land and 97 feet of beach.

Connecticut’s “anti-tuberculosis army” was already recognized for its efficiency, the quality of its sanatoria and medical and surgical staffs, and its use of modern treatment methods. The state already operated four sanitoria. The Undercliff facility in Meriden, for example, specialized in treating children with pulmonary tuberculosis, while adults were treated at Uncas-on-Thames in Norwich, Laurel Heights in Shelton, and Cedarcrest in Hartford. According to commission narratives, Connecticut was the first state to officially, and aggressively, use sunbaths, or heliotherapy, to treat bone and glandular tuberculosis. But a larger Oceanside facility, also to be named Seaside, was needed.

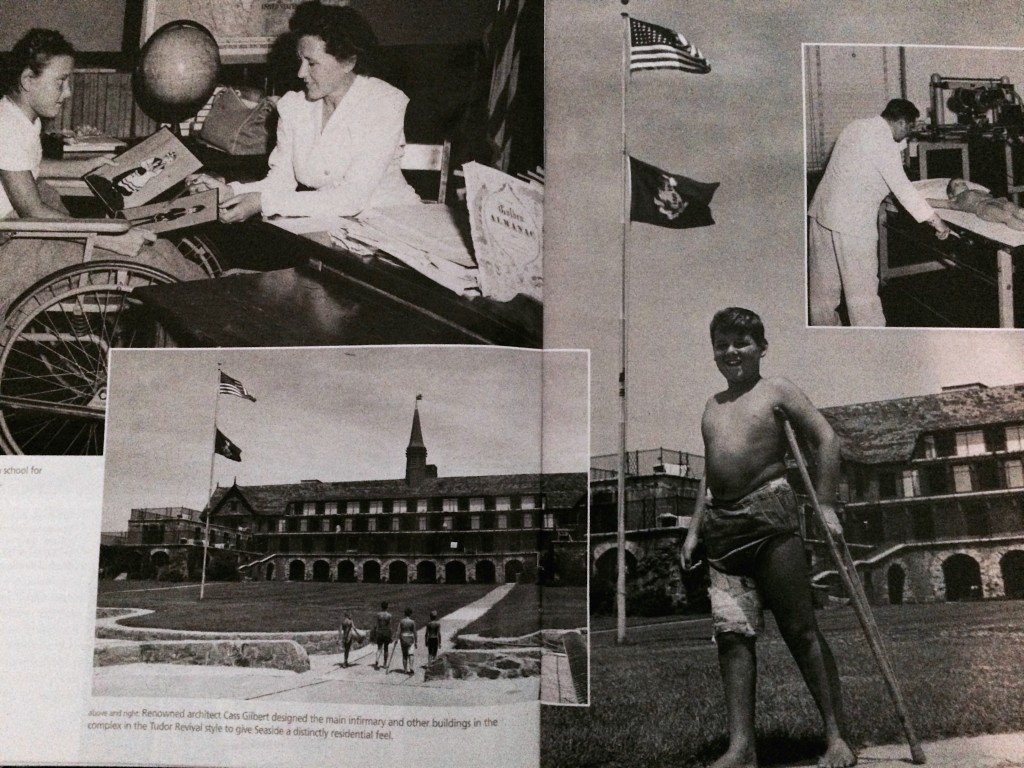

Renowned architect Cass Gilbert (1859 – 1934) designed the original buildings in the new Seaside complex in Waterford, including the main infirmary, (later named for Dr. Maher), the superintendent’s house, the nurse’s dormitory, and the Duplex House, which housed medical staff. Gilbert designed the complex in the Tudor Revival style, a departure from the Colonial or Classic Revival styles favored at the time. He designed Seaside between commissions for the Woolworth Building in New York City (finished in 1913) and the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C. (built in 1935), among other distinguished projects, including several others in Connecticut. By choosing the Tudor Revival style, he gave Seaside a distinctly residential, not institutional, feel. Gilbert died in England just weeks before the building’s official dedication.

When it opened in 1933, the new Seaside sat on 28 acres and had 1,700 feet of beach, with beds for 195 patients, more than three times the Niantic facility’s capacity. The new facility took children with bone and glandular tuberculosis from the original Seaside. “Here on the porches behind the blue-tinted railings the naked, bronzed children peered down smiling on the guests,” wrote the commission in its review of the dedication. Dr. John F. O’Brien was Seaside’s first superintendent, assisted by Dr. Joseph E. Strobel as resident physician and Nellie Rippin as head nurse.

Children spent as much time as possible exposed to the sun’s rays as part of their treatment at The Seaside. They played sports, took lessons, ate, read, and played music outside year-round, either on the beach, the lawns, or the three levels of south-facing porches. The Seaside had a school for students of all ages, and many “graduates” attended college.

In the first two years, only 5 of the 59 patients (36 boys, 23 girls) treated at the new Seaside died, while 18 were discharged as “apparently cured.” Another five left “improved,” and one left despite being classified as “unimproved.” According to commission records, length of stay was varied: many patients stayed six to 12 months, while others stayed less than three months.

By the time of the commission’s report in mid-1936, the new Seaside had a waiting list of 200 children. By mid-1938, Connecticut’s death rate from tuberculosis dropped to 36.8 per 100,000 deaths. By 1939, it was 32.4 per 100,000. Compare that to 1880, when 243.6 of every 100,000 deaths in Connecticut were from tuberculosis.

In fact, the number of children applying for entry to Seaside dropped so significantly that by mid-1944, Undercliff began admitting adults, and all of Undercliff’s young patients were transferred to the Seaside, regardless of their type of tuberculosis. The decline in bone and glandular tuberculosis in children allowed even a few adults to be given beds at Seaside to receive heliotherapy. By 1947, antibiotics were being used to treat the disease, with widespread success. Early detection also played a role as mobile X-ray units canvassed the state checking high school students for signs of incipient disease. New armed forces recruits also were routinely X-rayed.

By the early to mid-1950s, tuberculosis became curable with antibiotics that required limited bed rest and could be given in a regular hospital setting. This happy development spelled Seaside’s end. All of its patients were transferred to the Uncas-on-Thames facility in Norwich by 1958. In 1961, the state Department of Mental Retardation took over the vacant campus serving the southern part of the state. It remained in use as a residential facility for the mentally retarded until the mid-1990s.

Mark H. Jones was the archivist for the State of Connecticut. Ann Harrison was a member of the Connecticut Explored editorial team.

Read More!

Architect Cass Gilbert also designed:

“Glamour and Purpose in New Haven’s Union Station,” Spring 2013

“Longer Lasting Than Brass: Waterbury’s City Hall Restored,” Fall 2011