By Elisabeth Petry

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2019

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

My mother, the best-selling novelist Ann Petry, wrote in an essay, “Four generations of my family have been born in Connecticut.” She also said she was born in 1912, she got married on February 22, 1938, and her maternal grandfather had married three women named Anna. Not one of these statements is true. A few proved almost impossible to refute, but I had a great deal of fun—and an occasional migraine-level headache—in the process of fact-checking my own mother for various book projects and a documentary film about the family.

My mother, the best-selling novelist Ann Petry, wrote in an essay, “Four generations of my family have been born in Connecticut.” She also said she was born in 1912, she got married on February 22, 1938, and her maternal grandfather had married three women named Anna. Not one of these statements is true. A few proved almost impossible to refute, but I had a great deal of fun—and an occasional migraine-level headache—in the process of fact-checking my own mother for various book projects and a documentary film about the family.

Along the way I encountered myths and confusions that others propagated: great-great-grandmother Lydia Lane saw General George Washington, Uncle Bill’s middle name was Howard, and Connecticut’s first licensed African-American female pharmacist was born Anna Louise James.

My mother recounted her tales following the precept of her teacher of fiction at Columbia University, Mabel Louise Robinson, who said in a workshop that “truth is a millstone” around the neck of a writer. Mother also wove her narratives in aid of larger truths. Those truths still hold, regardless of the accuracy of the underlying details. Each narrative taught a greater lesson about human nature, or race relations, or economic survival.

When Mother wrote in Contemporary Authors (Vol. 6, Gale Research, 1988) that she was the fourth generation of her family born in Connecticut, she deepened her roots to make a point. Though she could call herself a “birthright” New Englander, as an African American, the Yankee majority did not accept her. She felt rejected because children threw rocks at her as they chased her home from school, calling her “nigger.” An adult used the same language, saying she shouldn’t join her Sunday school class on the beach.

Four Generations? Mother’s Mother’s Side

Mother was born in Saybrook, Connecticut in 1908, though the year has been reported as 1909, 1911, and 1912. Her mother, Bertha Ernestine James, was born in Hartford in 1875. But her mother’s mother, Anna Estelle Houston, was born about 1844, enslaved in Alabama, probably on a plantation near Montgomery. The place of birth on the marriage license on file with the Hartford Bureau of Vital Statistics was New Orleans, though that seems less likely. (Anna Houston also followed a practice of women throughout time by subtracting eight years from her age, probably because she was older than her husband, Willis S. James.)

While researching Ann Petry and the James Family Letters, a documentary I am producing with my cousins Ashley James and Kathryn Golden, I discovered that Anna did not arrive in Connecticut until she was about six years old. Her daughter, Helen James Chisholm, wrote an unpublished manuscript, “Unto the Third and Fourth Generations,” now in the Frank P. and Helen Chisholm Family Papers at Emory University. According to Helen, Anna came North in 1850 with her mother and brother.

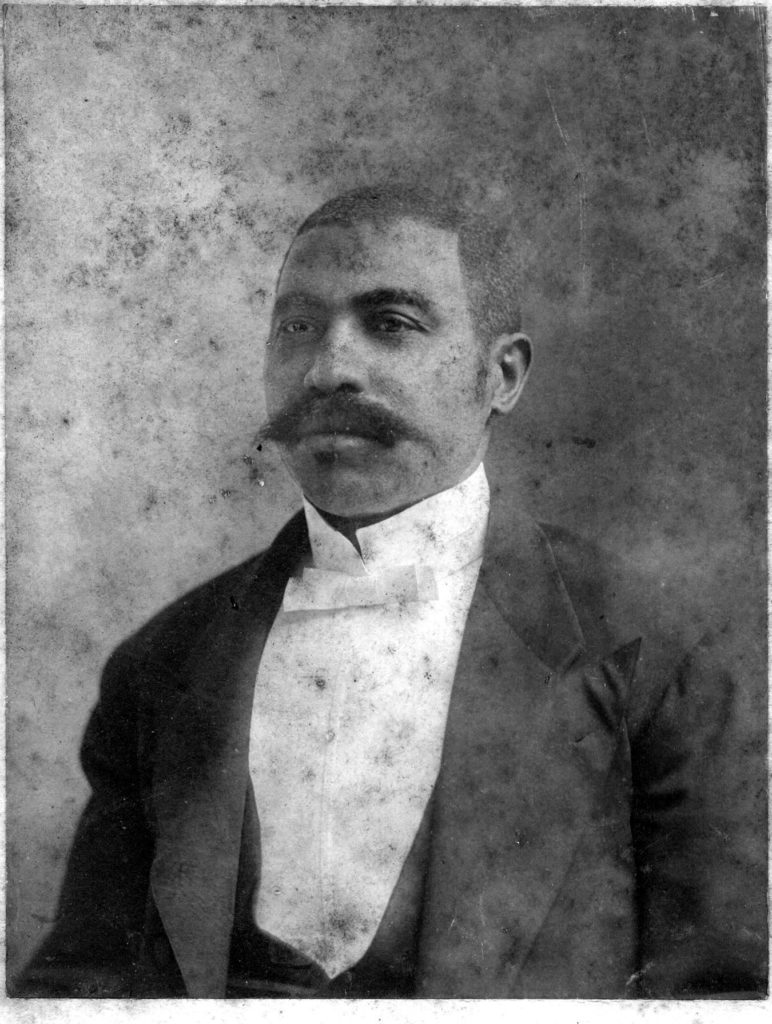

Willis Samuel James, before 1891, Elisabeth Petry’s great-grandfather, named Sam when he was born enslaved in Virginia. Courtesy of Elisabeth Petry

Helen writes of her journey through the Alabama countryside in the early 1900s as she attempts to locate the unnamed town near where her mother was born. She fails but recounts the harrowing story of how Anna’s father, the son of a wealthy planter, brought his children and their mother to New Haven. When he returned South, according to Helen, his father’s family had him killed for stealing their “property.” This is a story I’ve yet to research.

Mother’s grandfather, Willis S. James, was also from the South and anonymous as far as the commonwealth of Virginia was concerned. Virginia never maintained records of the enslaved by name. Researchers can only hope that the planter who bred his people like livestock had recorded a name and birthdate in his studbook. The Virginia Department of Health responded to my query in 2001: “There are no records prior to 1853, and there was no law for the registration of births and deaths between 1896 and June 14, 1912.” Documents from after Willis’s arrival in Connecticut proved unhelpful, giving his birthplace variously as Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania County, Falmouth, or Richmond, Virginia.

The most heartbreaking part of these omissions and confusions is that today no physical evidence remains of Anna and Willis’s last resting place, though there was such evidence as recently as 2003. Ashley and I had revelled in the discovery of the graves of our great-grandparents in Hartford’s Old North Cemetery. We located the family plot in the rear, in the colored section, between the Jewish families and the Irish Catholics. We returned several years later to discover the only remaining stones dated from the 1950s and belonged to Willis’s oldest son and his wife. A tree had apparently broken some of the gravestones. No one has ever responded to my queries about what happened or whether the stones could be restored.

Four Generations? Mother’s Father’s Side

On her father’s side, Mother was the first generation from Connecticut. Her father, Peter Clark Lane Jr., was born in New Jersey in 1871 or 1872, though he told people he came from Madagascar. He and his parents and younger brother moved to Hartford when he was about three. He did not arrive with an entire extended family as Mother wrote in her short story “The New Mirror” and in the Contemporary Authors essay. In fact the family began to move to Hartford by ones and twos and threes beginning in the mid-1860s.

The tale, which the family came to call “Throw that baby down to me,” illustrated the Lanes’ determination in the face of opposition. Mother’s great-grandfather, P.C. Lane, supposedly sailed to Hartford with a wife and six children, including a baby, along with all their furniture and livestock. As the boat approached the pier it backed up, preparing to make the final approach. The landlubbers didn’t understand and thought they were headed back to “Jersey.” P.C. jumped and ordered the adults to follow, yelling, “Throw that baby down to me!” But he never lived in Connecticut, and while I was researching Can Anything Beat White? A Black Family’s Letters (University Press of Mississippi, 2005), I found a handwritten obituary that began, “Died at New Germantown, N.J., April 5, 1910 Peter C. Lane (colored).” It recounted his life as an enslaved man, his marriage, and a fire that destroyed his home there.

P.C.’s widow, Lydia Ann, one of Mother’s paternal great-grandmothers, was also born into slavery. She did move to Hartford after P.C.’s death and became a minor celebrity. The Hartford Courant ran a story in January 1924 with the headline “Mrs. Lydia A. Lane Active At 105.” She died that December and was touted as “Hartford’s oldest citizen and the only great-great-grandmother in Connecticut.”

Lydia regaled her family with tales of watching George Washington and his men crossing the Delaware. Reference was made to what “those crazy white men” were doing out on the river in the middle of winter. It didn’t take much to figure out that though Lydia was old, she wasn’t that old, having been born more than 40 years after the event.

Another lesson repeated itself during my search for my ancestors. Each time it went extra-territorial, I appreciated the accuracy and scope of Connecticut’s vital records. While I found gaps in Hartford and New Haven, this state has far more complete information than New Jersey or Virginia.

Numbers Game

As I recounted in At Home Inside: A Daughter’s Tribute to Ann Petry (University Press of Mississippi, 2008), my mother acknowledged six birthdates and hid the date of her marriage. Some of this was a testament to her creativity, while sometimes it reflected the vagaries of poor record-keeping. The doctor who delivered her started the confusion because he waited to file the birth certificate and apparently wrote down whatever date came to mind. After publication of her groundbreaking novel The Street in 1946, she wrote to her mother regarding a magazine article about her. “Helen [her sister]will undoubtedly hoot when she sees some of the dates in it, especially my birth date. I haven’t known exactly what it is for years, so when asked for it over the telephone two or three months ago I simply made one up.” Eventually she decided it really didn’t matter, replying to a letter, “I was born October 12, 1908 in Old Saybrook, Connecticut—but with apologies to Tina Turner, what’s age got to do with it?”

Her actual wedding date was a secret she kept for her entire life. After she died, I found a Certificate of Marriage from Mount Vernon, New York, bearing the date March 13, 1936. “What about February 22, 1938, when Anna Houston Lane wed George David Petry in Saybrook?” I wondered. She always said she and my father had selected the date because friends and family had the day off for George Washington’s actual birthday. When confronted, my father looked embarrassed as I held out the piece of vellum. He explained that they had indeed married in 1936, but two years later Mother said she couldn’t deceive her parents any longer, and they had a ceremony in her parents’ living room. As far as the family was concerned, it became official in 1938.

Anna Who?

Mother and the rest of the family said the patriarch, Willis S. James, was married to three women named Anna. It’s true that his second wife was Anna Estelle Houston and his third wife was Anna Mathilda Phillips. But his first wife, who we thought was named Anna Webb, was a mystery. I was never able to find anyone with a similar name living in Westchester County, New York, where the family claimed she was born. One of her descendants said the last name was Jackson. Others indicated her first name was Johanna, surname Anderson. All I could establish was that she and Willis were living on Farmington Avenue in the coach house belonging to the Jewell family when she gave birth to their son Charles Howard James in 1866.

Years later I had one of those experiences that keep genealogists plodding through records. I located her and the rest of her family and discovered that her name was Hannah Derby or Darby. The clue was Wesley Derby, who in the 1900 census was residing in the household of his brother-in-law, Daniel Anderson, in Mount Vernon, New York. Then I located Wesley in 1880 next door to a farmer named Charles Darby, whom I traced back to 1860. When I saw that listing, I cried. There was Charles with Harriet, an adult. Children in the household included Wesley and Hannah E. Darby.

What’s in A Name?

While the Lane and James families begin in the tragedy of slavery, I envision the subsequent acts as a series of farces with people changing names and popping in and out of the picture.

The first to make his entrance is the brother of Mother’s maternal grandmother Anna Houston. In 1864 Charley Houston was living in New Haven and working as an apprentice carpenter when, during the waning days of the Civil War, he ran away from home, changed his name, lied about his age, and enlisted in New York’s Lincoln Cavalry. Charles Hudson passed for white then and at various times later in life, but he maintained contact with his sister’s children until his death in 1934.

Anna Louise James, the author’s great-aunt, was born Louise Cleggett James. Graduation photo, Brooklyn College of Pharmacy, 1908. Courtesy of Elisabeth Petry

One mystery I’ve never solved is the name change for Anna Louise James, youngest daughter of Willis and Anna Houston, born in Hartford on January 19 or 20, 1886. She bore the name Anna L. James in the 1900 census, and as Anna Louise James she operated The James Pharmacy in Old Saybrook for more than 40 years. Anna Louise is the name on her death certificate, but her birth certificate lists her as Louise Cleggett James, and the family called her Louise.

Willis Howard or Herbert James, also known as Leon or L. J. St. Clair, son of Willis S. James and Anna Estelle Houston. Courtesy of Elisabeth Petry

Her brother, Willis H. James, oldest son of Willis S. and Anna Houston, engaged in deliberate obfuscation. Sometime after he returned from fighting in the Philippine-American War, he adopted the alias Leon or L.J. St. Clair. His older sister Bertha compounded the mystery when, a few months before he died, she changed the middle name on his birth certificate from Howard to Herbert.

Willis/Leon may or may not have been married. According to an application filed with the U.S. Social Security Administration, Leon James and Mamie Boatwright had a son named Howard, born in New Britain on February 14, 1900. The town clerk had no record of the birth, nor could I find a record of Howard’s death, though his aunt Bertha wrote in the family Bible that he died December 24, 1944 in Pelham, New York, “hit by bus.” Another of Willis/Leon’s sons was reportedly named Leon. But to us Willis/Leon was known as Uncle Bill. My mother wrote on one of her lists of family members that Uncle Bill “never married, had five children.”

Middletown’s reference librarian Denise Russo provided crucial assistance when I was trying to locate L.J. St. Clair (a.k.a. Willis H. James) in Jacksonville, Florida, where he seems to have traveled after escaping a Georgia lynch mob. She sent a request to find city directory listings for two addresses and received the following reply from the Jacksonville Public Library: “The area of town requested for search contains no resident properties. The area is railroad acreage; no family names are listed.” Chances are Uncle Bill had no home but the rails.

I never have known what to make of one surname mystery on the Lane side. The obituary for P.C. Lane gives Lydia’s name as King, daughter of Martin and Catherine who lived in Vliettown, New Jersey. The Lamington Presbyterian Church marriage record lists her as Kennedy. A query to the church yielded this answer: “I do not have a copy of a marriage license or certificate. However, in a listing on marriages by Rev. Blauvelt, it notes a Peter Lane married to Lydia Kennedy on September 27, 1845. BUT (emphasis in the original) LDS church records: Peter Lane m. Lydia van DerVeer 27 Sept. 1845.” Her death certificate has her parents as Theodore Kennedy and Catherine Riger. Even a family history consultant could not place Lydia on the correct family tree.

Compounding the problem, the New Jersey town where the Lane family resided also changed names. My grandfather was born in New Germantown, and a relative said that during World War I the people renamed it Oldwick because of anti-German sentiment. When my grandmother went in search of his birth record, she wound up looking in Germantown, Pennsylvania.

These unsolved mysteries exemplify poor recordkeeping and in some cases the invisibility of women and enslaved people, but in the end I believe my family was true to the Yankee heritage my mother rejected. Besides being thrifty and hardworking, they kept the secrets they carried.

My next mysteries to solve? Why does Anna Houston’s mother, Mary Ann or May E., have three dates of death and two places of burial in New Haven? Then I’ll research why my father’s first cousin has two death certificates, dated years apart, including one from Galveston, Texas, giving the cause as “gunshot wound, homicidal.”

Elisabeth Petry is a writer and editor who lives in Middletown. She runs a writing workshop for military veterans and is working on a documentary film about her family. She wrote “Just Like Georgia, Except for the Climate,” African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014).

Explore!

For more about Ann Petry

“Just Like Georgia, Except for the Climate,” Fall 2014

For more about Anna Louise James

“James Pharmacy,” Spring 2007