(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2020

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

While I was perusing the local inventor history folder in the New Haven Free Public Library, an undated slip of yellowing newspaper, with no masthead, fell out. It described a Black woman who in the 19th century had made an important contribution to American life and culture. Despite this achievement, most don’t know who she is. Her name was Sarah Boone, she was a dressmaker who lived in New Haven, Connecticut, and she invented a type of ironing board that made it easier to press the fashions of the day. Her achievement makes her one of the first Black women in the country to receive a patent, according to the African American National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Sarah (Marshall) Boone was born in Craven County, North Carolina in 1832 to Sally and Caleb Marshall, who were both enslaved to James Marshall. James Marshall was Sarah’s biological father. According to marriage bond records, on November 25, 1847, when she was 14, Sarah married James Boon (later Boone), a brick mason, and he, a free man, may have bought her freedom. The Boones continued to live in North Carolina, where their children William, James, and Mary Elizabeth were born.

The Boones moved to New Haven by 1856, according to New Haven city directories. Their Northern destination was popular among Black people from North Carolina: many Southern landowners traveled to New Haven during the hot summer months, taking their enslaved servants with them. These enslaved people established a network in New Haven willing to help newcomers like the Boones get settled.

Sarah Boone lived at 30 Winter Street (highlighted in yellow). The City of New Haven, Bailey & Hazen, 1879. Library of Congress

The Black community in New Haven was small but active. African Americans comprised 4.8 percent of the city’s population in 1850, according to census data and Robert Austin Warner’s New Haven Negroes: A Social History (Yale University, 1940). Many Black residents lived near the lower part of Dixwell Avenue of New Haven in an enclave of wood houses adjacent to the red-brick buildings of Yale College. Many of Dixwell’s residents worked for the college, and Dixwell Avenue was a vibrant part of town, eventually serving as the main street for the Black community. Along this avenue were grocery stores, a doctor’s office, and a big concert hall.

The Black churches were central to Black life, according to Warner, and Sarah Boone was a member of the Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church, as the May 9, 1889 New Haven Register documents. The Boones lived at several places before settling at 30 Winter Street, located a few blocks from Sarah’s church. The Boones owned this two-story wood home, and daughters Henrietta and Louisa were born there.

Sarah Boone was one of many dressmakers in New Haven, and the listing of her name in the city directory after 1861 and her proximity to Yale’s campus suggests that she made dresses for both Black and white clients, a common practice according to Rollins Osterweis’s Three Centuries of New Haven, 1638-1938.

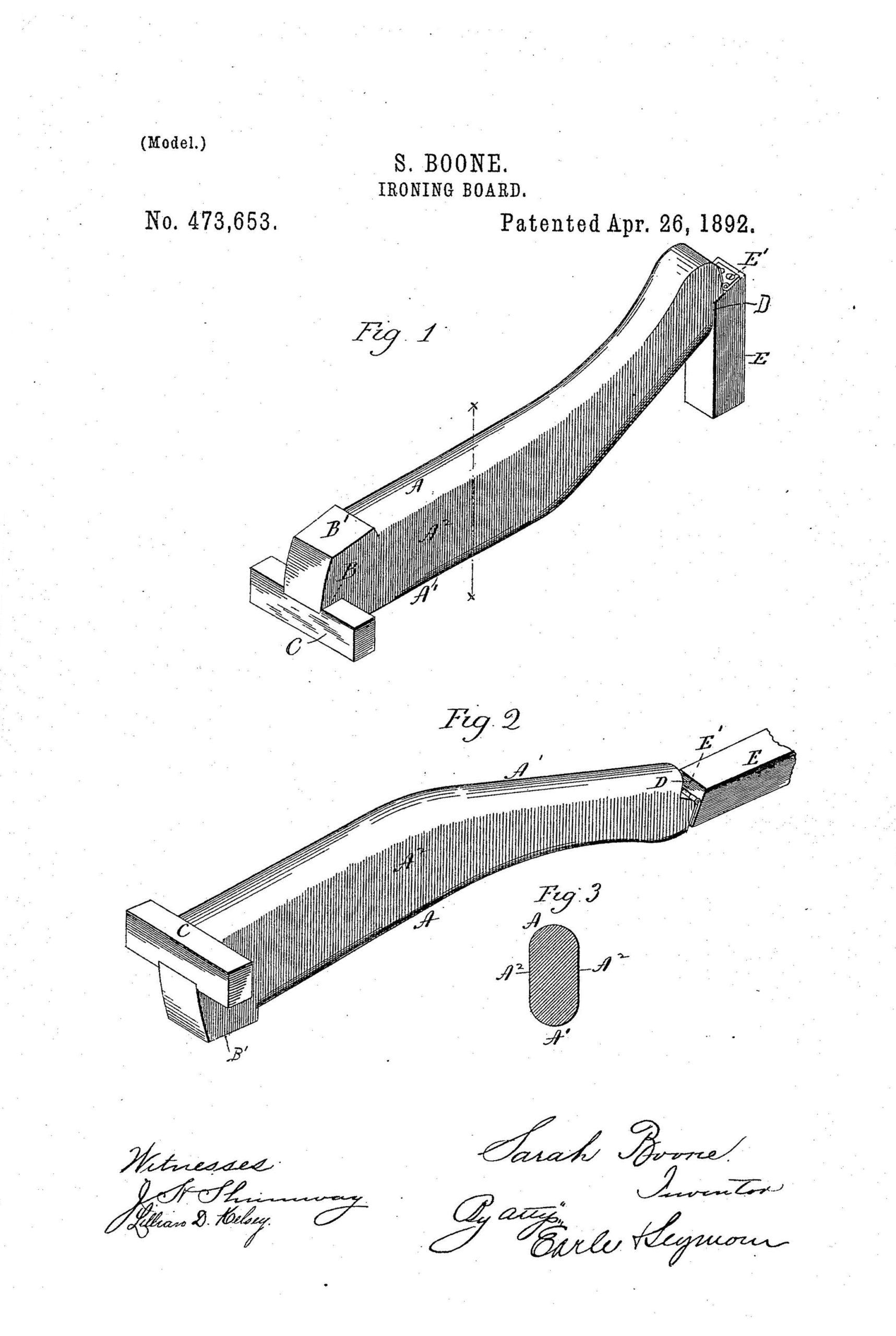

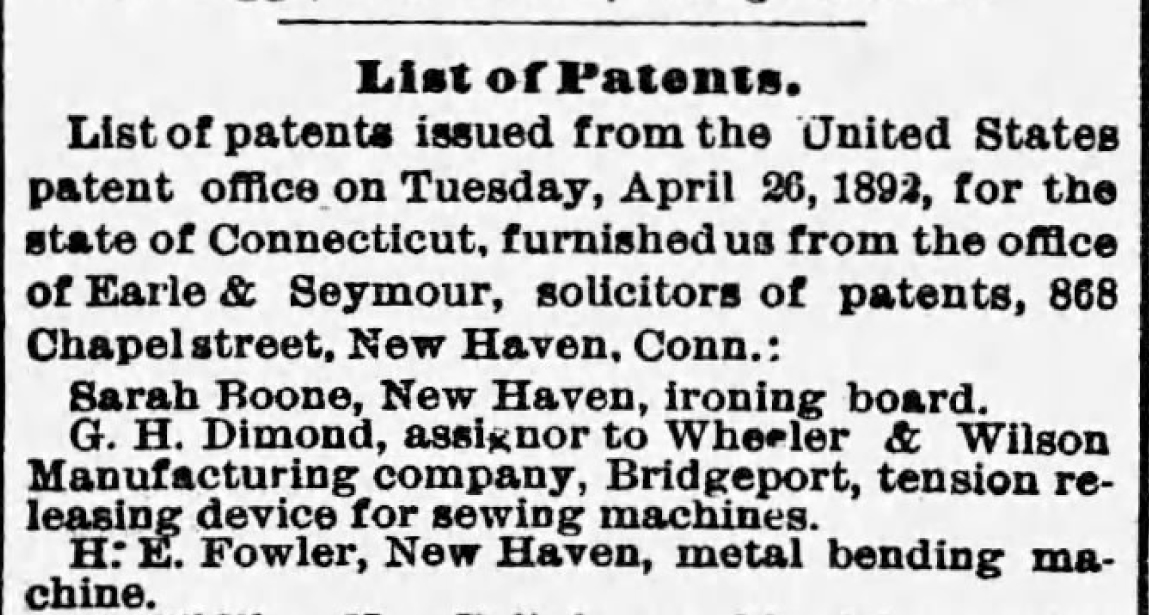

At some point, Boone apparently decided she needed a better way to iron dresses. Clothes commonly were pressed with an iron on a plank resting on top of two chairs, historian James Brodie explains in Created Equal: The Lives and Ideas of Black American Innovators (William Morrow, 1993). But the fashions of the day were not easily pressed by this method. New Haven, in Boone’s time, was the leading supplier of corsets in the United States, according to Edward Atwater in his 1887 History of the City of New Haven. These undergarments squeezed the midsection, giving a woman a shape like a figure 8. Sleeves were also fitted. Boone’s objective, as her patent application states, was “to produce a cheap, simple, convenient, and highly effective device, particularly adapted to be used in ironing the sleeves and bodies of ladies garments.” Sarah Boone applied for and received U.S. Patent 473,653 on April 26, 1892.

Boone’s feat is all the more meaningful because for most of her life she could not read. In the South, it was illegal to teach enslaved people to read. But, as an adult Boone took reading classes, possibly at her church, which, since the time of Rev. Amos Beman’s sermons on the topic in the 1840s and 1850s, had supported literacy for all of its congregants.

Boone died on October 29, 1904 at age 72 of Bright’s disease and is buried in the Evergreen Cemetery in New Haven. She left no papers or letters and the image attributed to her on the web is often of sculptor Edmonia Lewis. However, her patent casts a spotlight on an extraordinary life, signaling that in the 19th century there was a black woman inventor living in New Haven, and her name was Sarah Boone.

Ainissa Ramirez, Ph.D. is a scientist and the author of The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another (MIT Press, 2020).

Explore!

Find all of our stories about African Americans in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

Find all of our stories about products made and invented in Connecticut on our Connecticut Made TOPICs page.