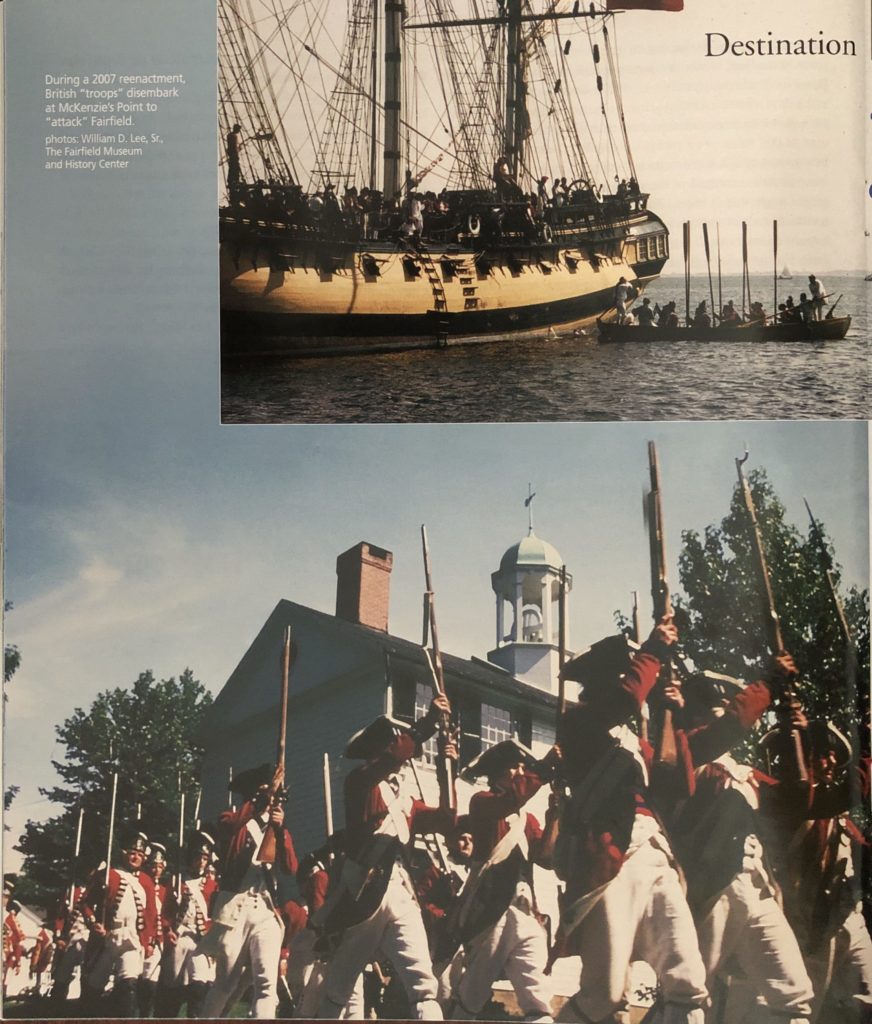

Reenactment of the British attack on Fairfield during the Revolutionary War, 2007. photos: William D. Lee, Sr., Fairfield Museum and History Center

By Adrienne E. Saint-Pierre and Walter D. Matis

(c) Connecticut Explored, Spring 2009

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

“A sad example was it, to witness how one of the best laid out little towns became a mass of flames,” wrote Lieutenant General Moriz Adolf von Wissenbach, a sympathetic Hessian soldier, in his journal. He was referring to the British-led destruction of Fairfield, Connecticut, on July 7 and 8, 1779. 2009 marks the 230th anniversary of Fairfield’s destruction during the American Revolution.

British General William Tryon had ordered the Regiment Landgraf and Jaegers (German forces) to cover his troops’ withdrawal and had written protective orders for several buildings, including the Anglican Church, the Congregationalist Meeting House, and the ministers’ homes. His orders were ignored, resulting in the loss of both houses of public worship, 82 homes, 55 barns, 15 stores, 15 shops, 2 schoolhouses, the jail, and the courthouse. The losses at Greens Farms, Fairfield’s West Parish, added another 15 homes and 11 barns to the total, plus a Meeting House and several stores. Von Wissenbach’s sympathies aside, many eyewitnesses largely pinned the blame for the conflagration, pillaging, and four civilian deaths on the Germans, whom Congregationalist minister Andrew Eliot referred to as “a banditti the vilest . . . ever let loose among men.”

“Why Fairfield?” residents likely asked themselves as they counted the loss of nearly half of the town’s 200 homes and the majority of its commercial enterprises. Although there were Loyalists among its citizenry, rebels had launched numerous annoying raids on British vessels from Black Rock Harbor (then part of Fairfield), where a small fort was situated on Grover’s Hill. The British response was punitive; more significantly, though, the town’s coastal location answered the military leaders’ new tactic of keeping the British troops close to their ships.

Two years earlier, in April 1777, the British had marched 24 miles inland from Compo Beach to Danbury. This maneuver had made them vulnerable to attack and resulted in the Battle of Ridgefield after they left Danbury in flames. Concentrating on coastal excursions targeting New Haven, Fairfield, and Norwalk was not only more expedient than fighting inland, it was a strategy, according to Sir Henry Clinton’s report to the King, “with a view to draw[ing]Mr. Washington from the strong Post which he occupied in the Mountains into Connecticut . . . .”

Thus it was on July 7, 1779, that Fairfielders awoke to a cannon warning from the fort at Black Rock, which was under Isaac Jarvis’s command. A British fleet had been spotted anchoring off the coast. With feelings of dread and uncertainty, residents prepared to defend their town, but no one predicted the extent of destruction that was about to occur. Some packed their belongings in wagons and went to stay with friends or relatives inland. Others felt their previous acquaintance with British officers, whom they believed to be honorable and polite, would protect them from harm.

Disembarking at Kenzie’s Point, two miles west of the town center, General Tryon and about a third of his troops marched into the town late that afternoon under fire from the fort and local militia. British General George Garth and the remainder of the 2,500-man force arrived a few hours later. They attempted to reach the “land side” of the fort at Black Rock by crossing Ash Creek, but when they found the planks of the bridge had been pulled up, their frustration apparently turned to retaliation. Systematically, they began burning homes.

William Wheeler, who lived in Black Rock, later recalled what he observed that fateful night when he was only 15 years old.

The town burnt all night—a cloud seemed to remain fixed in the west, from which issued frequent flashes of lightening; this joined to many a column from the flaming buildings & frequent discharges of cannon & musketry on the British guard placed around the town; the poor inhabitants, with no shelter, with no clothing but what they had on . . . . There were some instances of great bravery among the inhabitants . . . . A Mr. Tucker fired from his shop on the parade at the whole army only a few yards distant, & was wounded in the shoulder by them & taken prisoner. Mr. Parsons fired from a chamber into the road & killed a British officer; then running out the back door made his escape. The enemy . . . found an old negro bed-ridden; they said it was him . . . put the bayonet into him & burnt the house . . .

It was many years before Fairfield fully recovered from the destruction. In the slow process of rebuilding, its stature as one of the most influential and prosperous towns in the region diminished. In the decades following the war, the economic center of coastal Fairfield County shifted to Bridgeport and its superior harbor.

Explore!

Fairfield Museum and History Center

370 Beach Road, Fairfield

(203) 259-1598

Fairfieldhistory.org

Read more stories about Connecticut in the Revolutionary War on our TOPICS page.