(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2018

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

How are historic center-city churches faring today? The decline in attendance at traditional mainline churches has been widely reported; urban churches have had to withstand not only congregational but urban flight. Although we are witnessing a movement back to cities, does this represent hope for historically significant churches and synagogues?

For research I turned to Greg Farmer of the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation. Greg has routinely been summoned by historic churches that seek his advice about how to preserve and protect their structures. He observed that many so-called mainstream churches witness challenges to preservation, to say nothing of potential extinction. Often these buildings require substantial repair, and their congregations have limited financial resources to meet the need. Fortunately, the State Historic Preservation Office plays a partnering role in the preservation of Connecticut’s architectural legacy churches. Connecticut Trust, too, through its “circuit riders” such as Farmer, often consults and guides congregations to potential financial resources. One national resource, Partners For Sacred Spaces, can be brought in to advise and support churches in transition or in financial need.

Since the early 1970s churches nationwide have emerged as catalysts behind community redevelopment. Often it is a church that is the most stable physical asset in city neighborhoods because it has some level of financial and community support from a congregation. Community-development corporations working to address urban problems of blight, unemployment, poverty, and economic vitality often have church representatives at the core of their board of directors. The people I interviewed for this article all shared a common observation: as one considers the urban environment, it is the houses of worship that define the soul of a city. They saw the church or synagogue as the place-maker for the community in which it is located.

Here are three examples of how inner-city houses of worship are faring. All benefited from a community vision for the future of the building—as a church, or as something new.

Center Church, Hartford

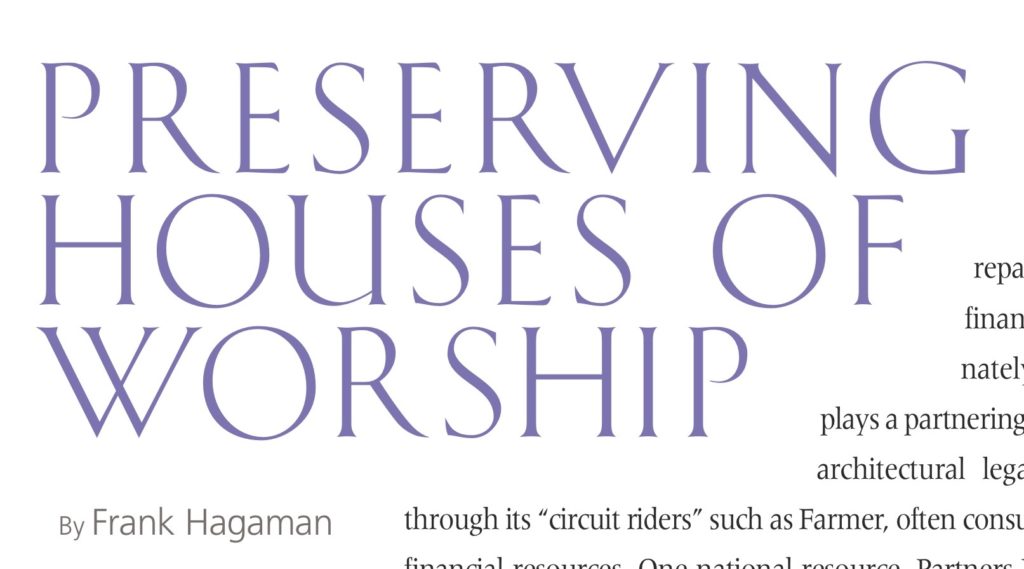

Center Church on Main Street bills itself as the “First Church of Christ in Hartford,” and its history dates back to 1632. The current building was erected in 1807 and is the fourth meetinghouse on the site.

The church is led by Reverend Shelly Stackhouse, who sees it as one with an urban mission. From her office she witnesses that the church is surrounded by the commerce of Connecticut’s capital city. She observes that Center Church represents a refuge from making and spending money. Indeed, the motto on the church’s website is “Seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you…and pray to the Lord on its behalf.” (Jeremiah 29:7)

With the help of a national non-profit, Partners for Sacred Places, Center Church has embarked on a $1.8-million restoration of its steeple, which is in bad repair, far worse than originally thought. Partners has offered a $250,000 matching grant to restore the structure. The steeple represents a beacon to people, signaling that there is something greater to be achieved. Center Church is alive with programs and outreach in Hartford. It hones to its mission to be a spiritual resource in Hartford and shares the opportunity to be a part of historic tourism in Hartford while embodying the spirit of downtown.

Charter Oak Cultural Center, Hartford

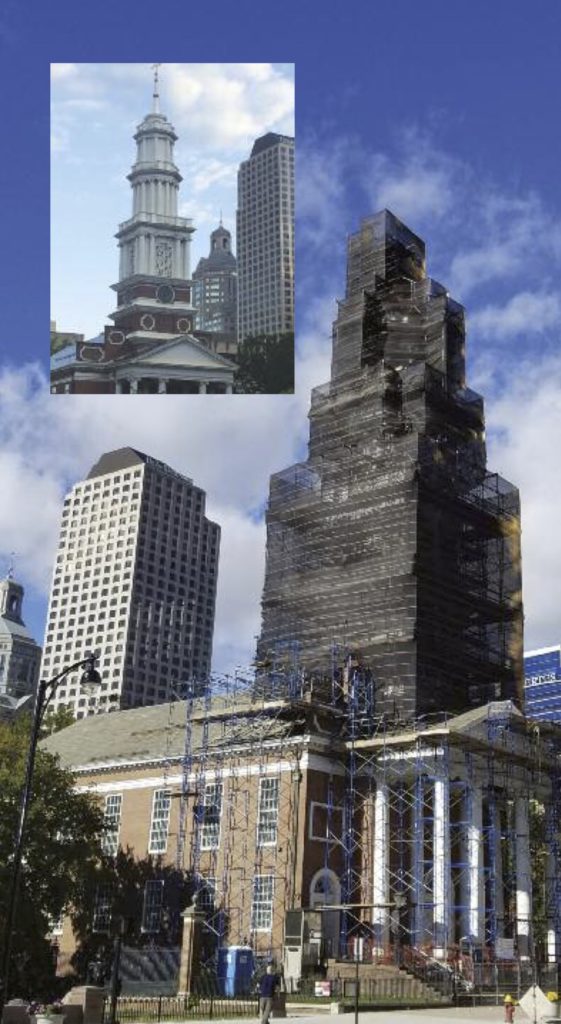

Charter Oak Cultural Center was built in 1876 as Temple Beth Israel, the first purpose-built synagogue in Connecticut. Designed in the Romanesque Revival style by Hartford’s well-known architect George Keller, it was a formidable presence in the growing downtown. In 1898 the temple was expanded. Over the years, however, members of the congregation began to migrate out of the city, and in 1936 the congregation moved to a new temple in West Hartford. Congregation Beth Israel continues to flourish in its new home.

Their old temple building was sold in 1935 to Calvary Temple Church. Faced with the same needs for more space and parking, Calvary moved to West Hartford in 1974. The synagogue was purchased by the Hartford Redevelopment Agency as part of a larger plan to redevelop the neighborhood. (See “Saving Hartford’s Amos Bull House,” Summer 2015) A group of concerned preservationists formed to purchase and preserve the temple. The Charter Oak Temple Restoration Association (COTRA) sought to repurpose the building as an urban cultural center. After years of restoration, the Charter Oak Cultural Center opened for community use.

Serendipitously, in 2001 the center was looking for a new executive director, and Donna Berman was seeking to find a “new enactment of my theology.” She is an ordained rabbi and, as a newly minted Ph.D., learned of COTRA’s search for an executive director. Her vision was to use the temple to “lift up the tent” and invite people to a place where their lives could be transformed through cultural expression. Under her leadership Charter Oak Cultural Center continues to thrive as a place of learning, performance, expression, and healing. Its sanctuary is in constant use and demand.

Charter Oak Cultural Center is known as a place for the homeless of Hartford. The center publishes a newspaper written and distributed by homeless individuals. Rabbi Berman has added education programs for the homeless in partnership with Goodwin Community College that offers free enrollment to students who complete the cultural center’s courses. One successful student is planning to study to become a lawyer.

The center has a youth arts institute that has enrolled 1,500 artists and performers. There is a community garden where vegetables are grown and given away to anyone who cares to harvest. The center is lively, busy, and active all the time. Once again, this house of worship has become a community anchor, this one with a mission of social justice.

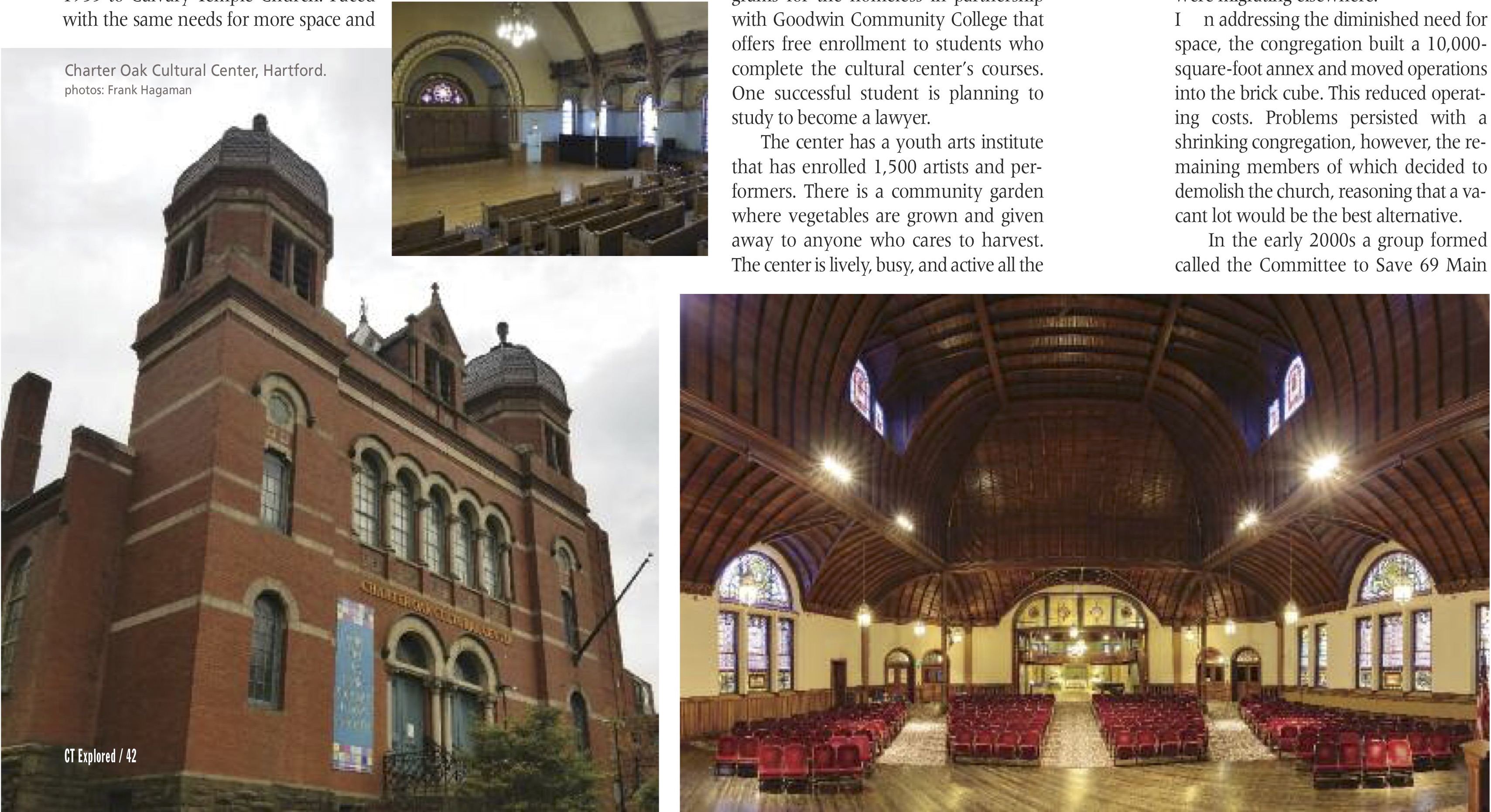

Top & left: Charter Oak Cultural Center, photos: Frank Hagaman. Right: Trinity-On-Main, photo: (c) Steve Adams Photography

Trinity-on-Main, New Britain

The first meetinghouse of the Trinity United Methodist Church was a roughly finished barn built in 1815 and moved to 230 Arch Street in 1854. In 1856 a second building was erected on the corner of Walnut and Main streets. In 1889 the third and present building was dedicated. In the 1920s the church began witnessing a slow but steady decline of membership into the 1980s and 1990s. This mirrored the urban challenges of New Britain, a city whose manufacturing businesses were migrating elsewhere.

In addressing the diminished need for space, the congregation built a 10,000-square-foot annex and moved operations into the brick cube. This reduced operating costs. Problems persisted with a shrinking congregation, however, the remaining members of which decided to demolish the church, reasoning that a vacant lot would be the best alternative.

In the early 2000s a group formed called the Committee to Save 69 Main Street to preserve the building. As a historic structure that sits on the city’s main square, Trinity is recognized for its strategic importance in the preservation of downtown New Britain. A study was commissioned to explore a highest and best use for the building. It suggested that the sanctuary would lend itself to a first-rate performance space. Architecturally beautiful, the hall embodies the spectacular design and materials that one expects in a complex and monumental Richardson Romanesque structure.

With help from various New Britain charitable foundations the building was secured from demolition and reopened as Trinity-On-Main in 2009. According to managing director Gary Robinson, the venue now hosts an array of events, performances, and other happenings. Robinson freely admits that Trinity operates strictly on a break-even basis. This is always a challenge, considering the physical maintenance demands of such a beautiful historic site.

Hartford Preservation Alliance

Center Church was able to turn to the Hartford Preservation Alliance for assistance. In 1997 a group of dedicated preservationists recognized that the historic fabric of Hartford was constantly under siege from developers that preferred to tear down rather than restore. HPA built on the legacy of an earlier organization, the Hartford Architecture Conservancy, which operated from the 1970s until the late 1990s. A 1997 Hartford Courantstory noted that HAC had “changed the face of Hartford,not only saving or helping to save hundreds of historic buildings—and at least once a whole neighborhood—but finding new uses for those buildings as homes and offices.”

One of HPA’s most significant achievements is a preservation ordinance for Hartford. Adopted by unanimous vote of the Hartford City Council in May 2005, this ordinance, the first in Connecticut, provides limited but significant protections that help preserve “the unique architectural nature of the city’s historic neighborhoods.” It now stands as the model for other cities wanting to preserve and protect their historic assets.

By its 15th anniversary, HPA realized that its work would require a mission and vision that went well beyond the saving of the “gems.” I was hired to guide HPA to become a partner in community economic development. The board adopted a new strategic plan in 2014 to establish historic preservation as a leading force in Hartford’s urban design. And our guiding principle, to “envision a thriving Hartford whose future prosperity builds on a rich heritage through our historically significant architecture, sites and neighborhoods,” now informs our work. This vision addresses a challenge to make preservation matter in a city that struggles financially, that is diverse, and that has a homeownership rate well below the national average. Historic preservation must benefit everyone.

Today HPA has a robust and effective technical-assistance program to guide property owners in Hartford and the Greater Hartford Region. Connecticut is unique in offering both a commercial and a homeowner state-tax credit for restoration construction projects. HPA offers a one-stop resource for guidance on taking on restoration projects and how to pay for them. We now provide technical assistance for everything from restoring a porch rail and helping to redesign the Travelers Plaza to helping Center Church restore its steeple.

Frank Hagaman is the executive director of the Hartford Preservation Alliance.

This is the first in a 4-part series about the history of nonprofits in the Greater Hartford region, funded in part by the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving.