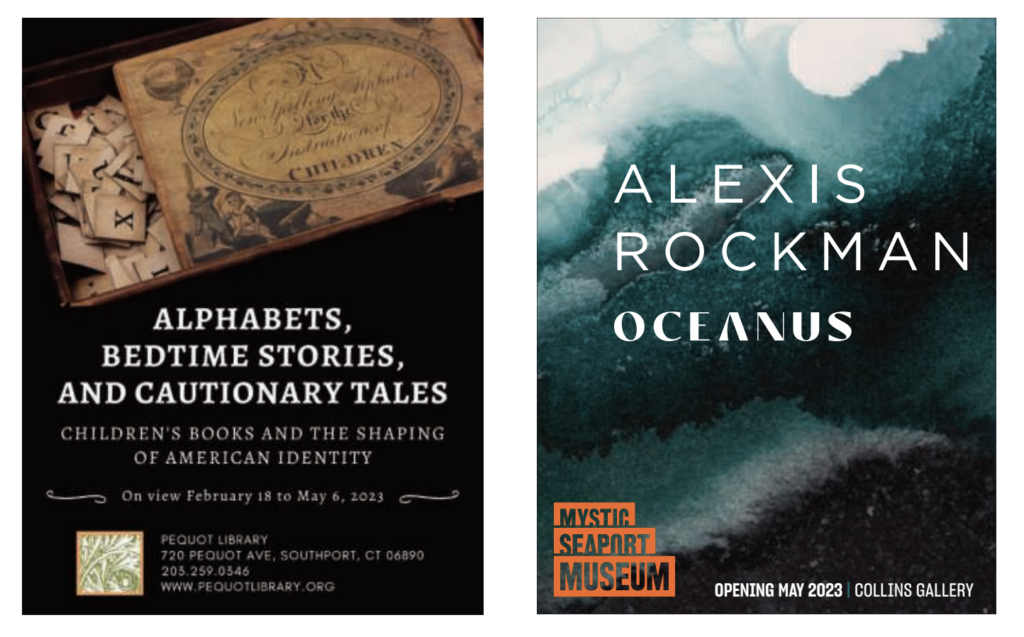

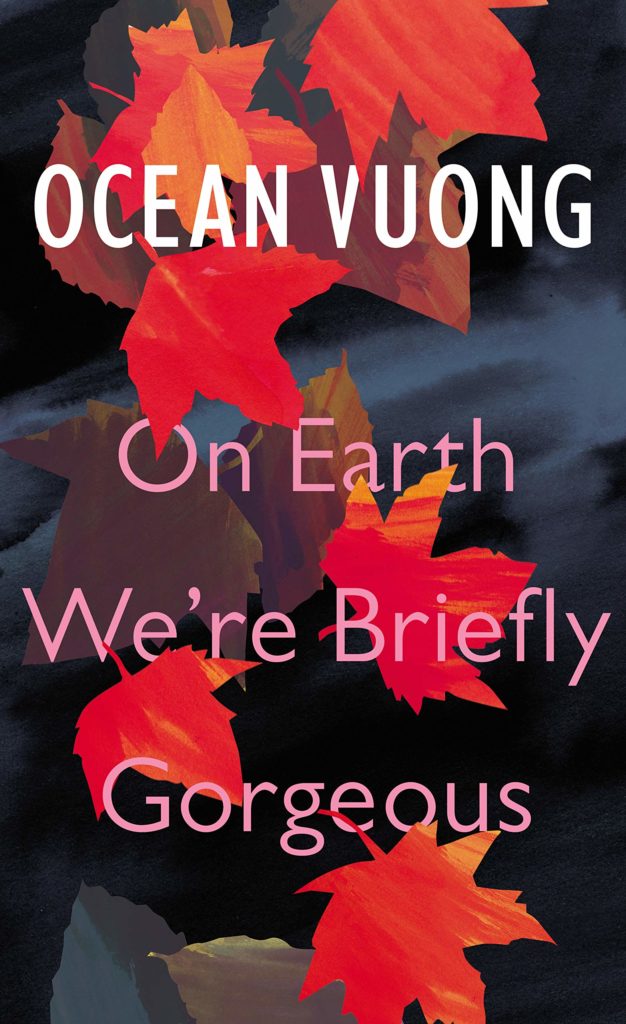

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Spring 2023

Vuong’s 2019 On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (Penguin Press, 2019) was selected as a Game Changer for its rich portrayal of Greater Hartford in the late 20th and early 21st century and for expanding our understanding of the Vietnamese-American experience in Connecticut. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous was recognized as the 2020 Mark Twain American Voice in Literature honoree and as the winner of the 2020 Connecticut Book Award.

Though a novel, the book is based on Vuong’s own life. As such, it deepens our insight into the richness of life in the poor, immigrant neighborhoods of Connecticut’s capital city, across the Connecticut River to East Hartford, north to the tobacco fields of Windsor, and south to the peach orchards of South Glastonbury. Vuong portrays important events in history, such as the Vietnam War and its aftermath, including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, domestic and child abuse, and intergenerational trauma. It explores the opioid crisis and LGBTQ and race issues with nuance, complexity, and compassion.

Vuong explained during the book’s launch at The Strand bookstore in New York City, “The goal of memoir is to arrive at historical truth, and the novel begins with truth and is realized by the imagination,” adding, “Writers of color are often pigeonholed into being conduits of an anthropological reality, in other words, we’re seen as tour guides to pre-made worlds rather than world makers ourselves.” Connecticut Explored acknowledges the power of this work to reveal to readers the historical truth and, beyond that, to gain a deeper understanding of the human experience.

Excerpt(s) from ON EARTH WE’RE BRIEFLY GORGEOUS: A NOVEL by Ocean Vuong, copyright ©2019 by Ocean Vuong. Used by permission of Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

We passed the tenement building on New Britain Ave. where we lived for three years. Where I rode my pink bike with training wheels up and down the linoleum halls so the kids on the block wouldn’t beat me up for loving a pink thing. I must’ve ridden down those halls a hundred times a day, the little bell clinking as I hit the wall at each end. How Mr. Carlton, the man who lived in the last apartment, kept coming out and yelling at me each day, saying, “Who are you? Whatare you doing here? Why don’t you do that outside? Who are you? You’re not my daughter!You’re not Destiny! Who are you?” But all that, the whole building, is gone now—replaced by a YMCA—even the tenement parking lot (where nobody parked since no one had cars), busted through with weeds nearly four feet high, is gone, all of it bulldozed and turned into a community garden with scarecrows made from mannequins thrown out by the dollar store of Bushnell. Entire families are swimming and playing handball where we used to sleep. People are doing butterfly strokes where Mr. Carlton eventually died, alone, in his bed. How no one knew for weeks until the whole floor started to reek and the SWAT team (I don’t know why)had to come bust down the door with guns. How for a whole month Mr. Carlton’s things were left out in a big iron dumpster out back, and a wooden hand-painted pony, its tongue-lolled face, peeked out of the dumpster’s top in the rain.

Trevor and I kept riding, past Church St. where Big Joe’s sister OD’d, then the parking lot behind the MEGA XXXLOVE DEPOT where Sasha OD’d, the park where Jake and B-Rab OD’d. Except B-Rab lived, only to be caught, years later, stealing laptops from Trinity College and got four years in county—no parole. Which was heavy, especially for a white kid from the suburbs. There was Nacho, who lost his right leg in the Gulf War and whom you could find on weekends sliding under jack-raised cars with a skateboard at the Maybelle Auto Repair where he worked. Where he once pulled a beautiful screaming red-faced baby from the trunk of a Nissan left in the back of the shop during a blizzard. How he let his crutches fall and cradled the baby with both hands and the air held him up for the first time in years as the snow came down, then rose back up from the ground so bright that, for a blurred merciful hour, everyone in the city forgot why they were trying to get out of it.

There’s Mozzicato’s on Franklin, where I had my first cannoli. Where nothing I knew ever died. Where I sat looking out of the window one summer night from the fifth floor of our building, and the air was warm and sweet like it is now, and there were the low voices of young couples, their Converses and Air Force Ones tapping against each other on the fire escapes as they worked to make the body speak its other tongues, the sound of matches, or flames sparked from lighters the shape and shine of 9mms or Colt .45s, which was how we turned death into a joke, how we reduced fire to the size of cartoon raindrops, then sucked them through cigarillo tips, like myths. Because eventually the river rises here. It overflows to claim it all and to show us what we lost, like it always had.

The bike spokes whirred. The smell of sewage from the water plant stung my eyes just before the wind did with it what it does with the names of the dead, swept it behind me. We crossed it, we left it all behind, the spokes ticking us deeper toward the suburbs. When we hit the pavement in East Hartford, the scent of wood smoke blown from the hills came down and cleared the mind. I stared at Trevor’s back as we rode, his brown UPS jacket, the one his daddy got from working there a week before getting fired after downing a six-pack on his break and waking up near midnight in a pile of cardboard boxes, now purplish under the moon.

The street lights fell away and the sidewalk led up to a grassy shoulder, which meant we’re heading up the hills, to the mansions. Soon we were deep in the burbs, in South Glastonbury, and the house lights started appearing, first as orange sparks flitting through the trees, but as we got closer, they grew into wide, fat sheets of gold. You could peer through these windows, windows free of steel bars, their curtains drawn wide open. Even from the street you could see the sparkling chandeliers, dining tables, multicolored Tiffany lamps shaded with decorative glass. The houses were so large you could look in all the windows and never see a single person.

As we climbed the road up the steep hill, the starless sky opened up, the trees fell slowly back, and the houses grew further and further apart from one another. One set of neighbors was separated by an entire orchard, whose apples had already begun to rot across the field, no one to pick them. The fruit rolled into the street where their flesh burst, puled and browned, under the passing cars.

“Let’s get out of here,” I said, chewing.

I picked up my [bike], the steel already wet with dew, and that’s when I saw it. Actually, Trevor saw it first, letting out an almost imperceptible gasp. I turned around and we both just stood there leaning against our bikes.

It was Hartford. It was a cluster of light that pulsed with a force I never realized it possessed.

Ocean Vuong. photo: Peter Bienkowski

______________