(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2014

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

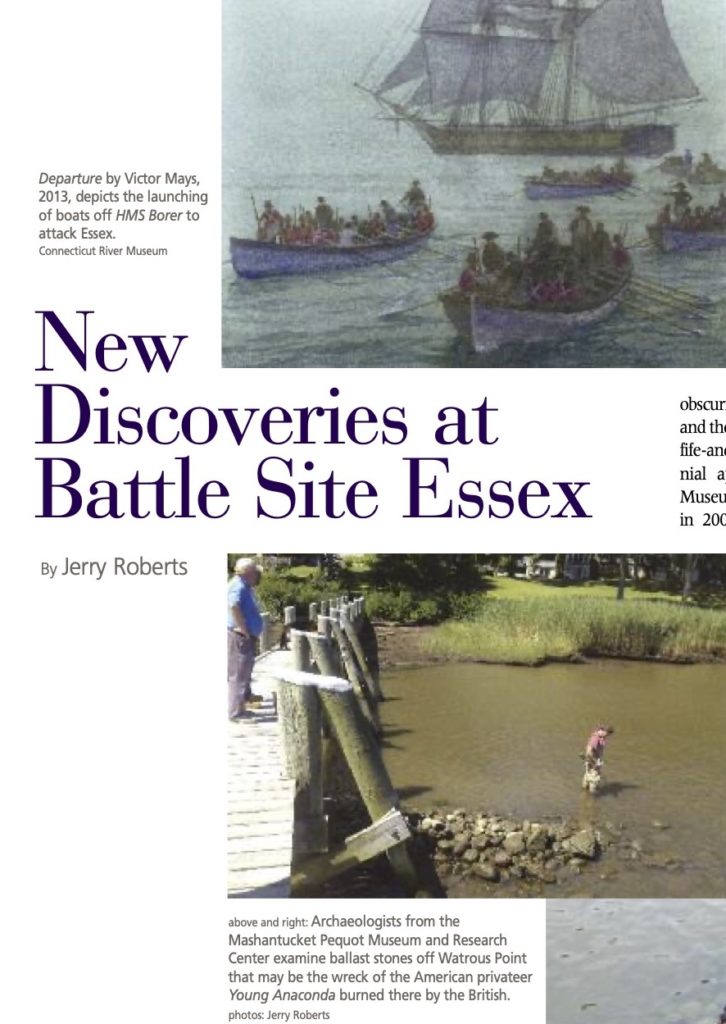

The British Raid on Essex (see “The British Raid on Essex,” Summer 2012) resulted in the largest single loss of American shipping during the entire War of 1812. On April 7, 1814, 136 British sailors and marines rowed six miles up the Connecticut River from warships anchored in the Long Island Sound to burn American privateers in Pettipaug, the village now known as Essex. Despite its being the largest military operation of the war in Connecticut, with the loss of 27 vessels, the episode slipped into obscurity, remembered only through folklore and the town’s annual Commemoration Day fife-and-drum parade. As the raid’s bicentennial approached, the Connecticut River Museum launched a major research project in 2009 to separate fact from fiction and advocate for state and national recognition of this important but nearly forgotten battle.

A grant from the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) funded research in archives on both sides of the Atlantic, resulting in official recognition of Essex as a state War of 1812 battle site in 2012. This in turn attracted a grant from the American Battlefield Protection Program, a division of the National Park Service, to fund the documentation and mapping of the battle site, a requirement for sites applying to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. To accomplish this we had to marry the known narrative of the battle to the landscape on which it was fought. This encompassed extant colonial roads, villages, and the river itself. It was a major endeavor, involving nearly $30,000 in grant money and dozens of dedicated professionals using metal detection, ground penetrating radar, and strategic digging to locate remaining physical evidence of the battle where possible.

To find that evidence—likely in the form of bullets, buttons, and cannon balls—we turned to Kevin McBride and the field archaeology team of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. As project battlefield historian I worked with Kevin and his team to help decide where to look and interpret what was found.

The battle took place over a seven-mile stretch of river from its mouth to Falls River Cove, a mile north of Essex. Key locations include the site of the old fort on Saybrook Point where the British first landed, the village of Essex, which the British occupied after a shootout with local militia, Ayres and Watrous points half way between Essex and Saybrook Point, and the high ground on both sides of the river now spanned by the Baldwin Bridge. This is where more than 500 American soldiers, sailors, marines, and militia created a gauntlet through which the British had to pass on their way out.

Each location offered its own challenges, but the efforts proved well worthwhile. Three months of fieldwork yielded a variety of artifacts in addition to those already in the collections of the Connecticut River Museum and the Essex Historical Society. All of this helped confirm that the battle was much more complex and larger then suspected. Through research we were able to put some myths to rest and at last identify the American traitor who piloted the British up the river for a $2,000 payoff. But the most surprising discovery we made was in the river itself.

Each location offered its own challenges, but the efforts proved well worthwhile. Three months of fieldwork yielded a variety of artifacts in addition to those already in the collections of the Connecticut River Museum and the Essex Historical Society. All of this helped confirm that the battle was much more complex and larger then suspected. Through research we were able to put some myths to rest and at last identify the American traitor who piloted the British up the river for a $2,000 payoff. But the most surprising discovery we made was in the river itself.

As the British left Essex on the morning of April 8, 1814, they took with them two newly built American privateers, the brig Young Anaconda and the schooner Eagle. The brig reportedly went aground near Ayres Point, and the Eagle anchored nearby. The British decided to remain there until nightfall to continue their escape under the cover of darkness. They burned the Young Anaconda, and the Eagle took sporadic musket fire throughout the day. The pivotal moment of the battle came at 7 p.m. when the British burned the Eagle as well and prepared to continue the escape in their six ships’ boats. As the sun set they were hit by an American six-pound cannon, which had been rushed into position. Two marines were killed, but the British proceeded down river and made it through the American positions to rejoin their ships by 9:30.

Two hundred years later, after extensive metal detection at Ayres Point turned up no additional artifacts, I got a call from Andy Carr, a local man who had attended one of my lectures about the battle. He told me that he believed the wreck of the Young Anaconda was actually under his dock off Watrous Point, a quarter mile to the north of Ayres Point. The history business is filled with wild goose chases, but you never know where they might lead. I took Kevin to visit Carr’s dock. We were amazed to find a classic pile of ballast stone there in the river 100-odd feet from the bank. Some quick research confirmed this location matched British reports that it was a mile and a quarter south of Essex and half a musket shot from shore. Based on this, Kevin deployed a metal detecting crew that found more than two dozen musket balls in the lawn nearby. Although still a work in progress, it seems we may have found not only the long lost wreck of the Young Anaconda but also physical evidence of a shootout between American militia and the British aboard the captured privateer Eagle.

This discovery was made just as I was putting the finishing touches on the book I was writing. I had to quickly re-write this pivotal chapter. As a result of more than five years of research, our team has been able to re-tell this key chapter in our state and national history and bring this important battle into the light of day at last.

Jerry Roberts is the former director of the Connecticut River Museum. His book The British Raid on Essex, the Forgotten Battle of the War of 1812 (Wesleyan University Press, 2014) is the definitive account of this dramatic 24-hour action.

Explore!

“The British Raid on Essex,” Summer 2012

Read all about the War of 1812 in our special Summer 2012 issue