(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2005/2006

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2005/2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Introduction

As I prepared to enter a graduate school program in historic preservation in 1977, my grandmother wanted to brag to her friend about my enrollment in a prominent university. Living in a tiny Ohio farm village, she was not clear what I was planning to study, let alone what I was going to do for a job. What was historic preservation? Her solution was to explain it as across between a real estate agent and a high school history teacher. Twenty-five years later, I still use this description. It has remained accurate as the modern historic preservation movement and I have grown up together. Mary M. Donohue

Heritage Matters: Creating Public Policy

Unprecedented economic growth in the post-World War II era was a mixed blessing for America’s cities, villages, and countryside. Historic buildings and sites were placed at great risk by massive public works projects such as interstate highways and urban renewal. Actual losses and the potential for greater destruction were foremost among the reasons for the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. The act had one rationale: the nation’s historical and cultural foundations should be preserved as living components of community life and development in order to provide the American people a sense of place and connectedness. Our historic buildings and neighborhoods were not to be preserved just as museums, but as vibrant repositories of our collective history.

Passed during an era of growing awareness of the environment, the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) took effect in the same year as the Department of Transportation act, which provided safeguards for both natural and cultural resources. These acts, plus 1969’s National Environmental Policy Act, established a national agenda for protecting our natural and built surroundings.

The NHPA put into place the preservation movement’s four essential tools: identification, evaluation, registration and protection. The act named the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior as the federal entity responsible for its execution, and, in 1967, each state governor was asked to name a state historic preservation office and designate an agency to work with the National Park Service — and the Connecticut Historical Commission, now a division of the Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism, was appointed. Since then, Connecticut has received more than $18 million from the federal Historic Preservation Fund — money that has been critical in fostering historic preservation throughout the state. The Historic Preservation Fund Grant-in-Aid program, the National Register of HIstoric Places, and the Certified Local Government Program are some of the far-reaching provisions of the federal law.

Tools of the Trade: Recognition and Registration

One of the specific purposes of the federal preservation law was to mandate the identification and documentation of historic buildings and sites. This led to the creation of the Connecticut Statewide Historic Resource Inventory, a database that in 2005 includes more than 70,000 buildings and 5,000 archaeological sites.

Of course, such a list is only useful if people can use it. “Our challenge in the next decade is to put this massive amount of information into circulation using new formats such as the Internet to ensure its use by the broadest constituency possible,” said Paul Loether, director of the Historic Preservation and Museum Division of the Commission on Culture & Tourism. HOmeowners, developers, mayors, and planners use the data as the basis for preservation planning, helping to ensure that growth and development occur without obliterating the past. Preservation Action, the national grassroots lobbying organization, states, “Without data…communities have been ill-equipped to deal with economic upheaval and abandonment in urban historic districts, nor the march of sprawl across their rural districts…(and) preservationists cannot participate as effective partners at the planning table.”

Similarly, the National Register of Historic Places is an inventory of buildings, structures, districts, sites and objects that merit preservation because of their significance in American culture at the local, state, or national level. SInce 1968, more than 50,000 Connecticut properties have been added to the National Register by the National Park Service; that list now documents the state’s history from as early as the Woodland Period (1,000 B.C. – A.D. 1,500) to the 1960s.

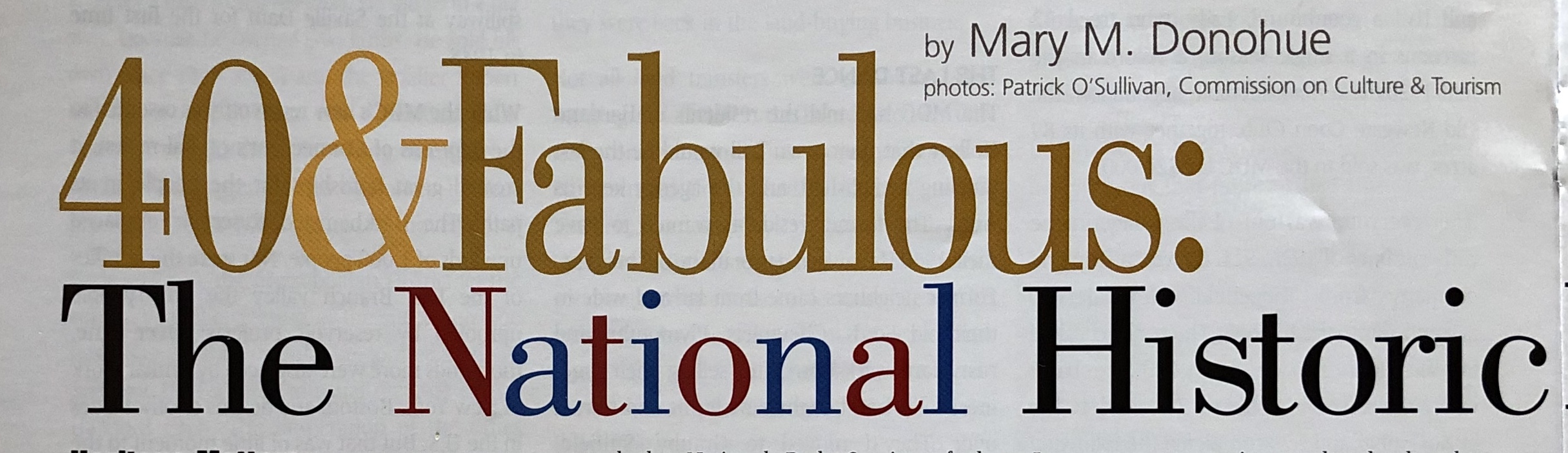

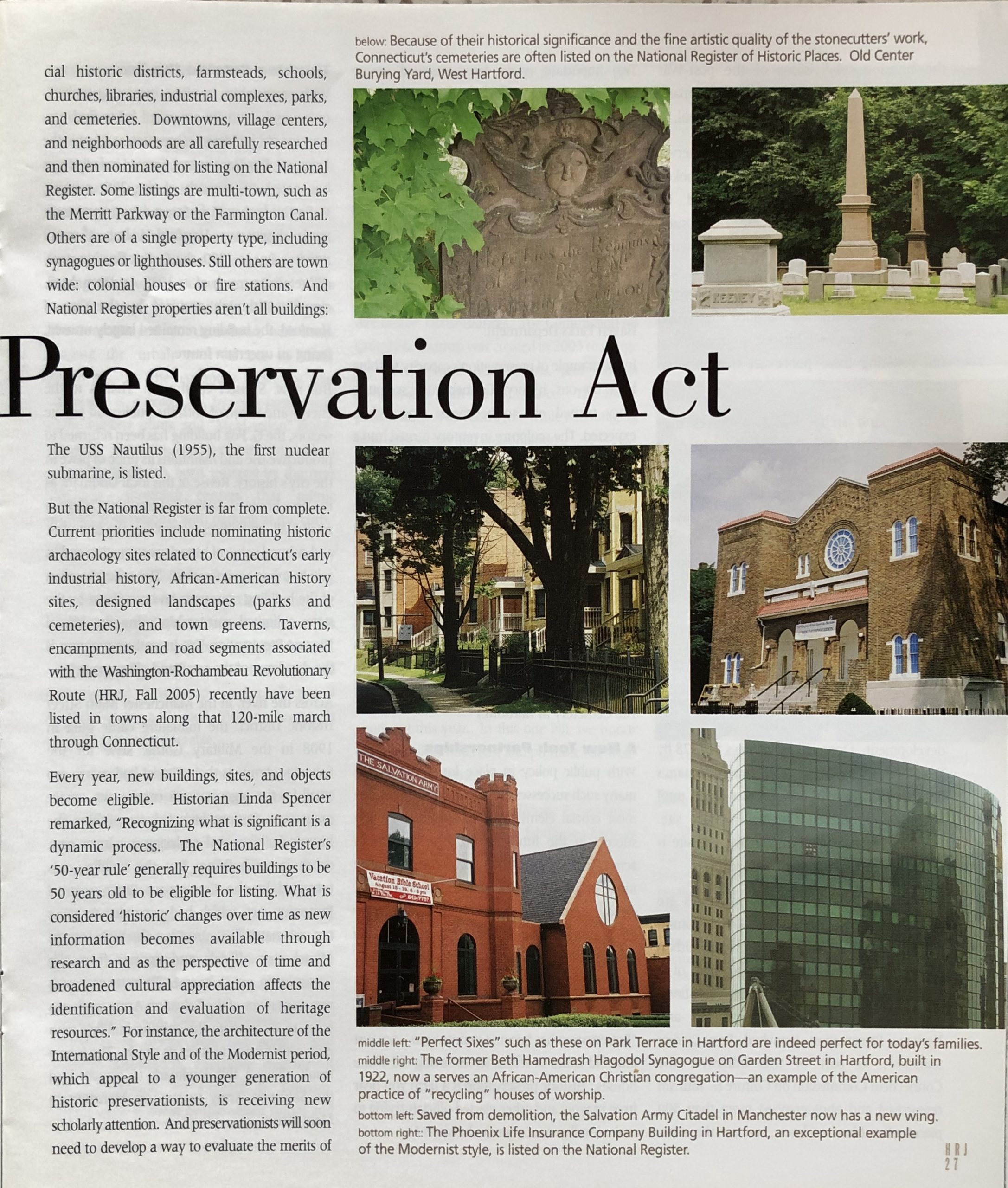

The list of National Register properties in Connecticut includes residential and commercial historic districts, farmsteads, schools, churches, libraries, industrial complexes, parks, and cemeteries. Downtowns, village centers, and neighborhoods are all carefully researched and then nominated for listing on the National Register. Some listings are multi-town, such as the Merritt Parkway or the Farmington Canal. Others are of a single property type, including synagogues or lighthouses. Still others are town wide: colonial houses or fire stations. And National Register properties aren’t all buildings: The USS Nautilus (1955), the first nuclear submarine, is listed.

But the National Register is far from complete. Current priorities include nominating historic archaeology sites related to Connecticut’s early industrial history, African-American history sites, designed landscapes (parks and cemeteries), and town greens. Taverns, encampments, and road segments associated with the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route (See “The ‘Conference’ State,” Fall 2005) recently have been listed in towns along that 120-mile march through Connecticut.

Every year, new buildings, sites and objects become eligible. Historian Linda Spencer remarked, “Recognizing what is significant is a dynamic process. The National Register’s “50-year rule” generally requires buildings to be 50 years old to be eligible for listing. What is considered “historic” changes over time as new information becomes available through research and as the perspective of time and broadened cultural appreciation affects the identification and evaluation of heritage resources.” For instance, the architecture of the International Style and of the Modernist period, which appeal to a younger generation of historic preservationists, is receiving new scholarly attention. And preservationists will soon need to develop a way to evaluate the merits of the housing subdivisions of the post-War period — structures that may have struck many as mundane but are now due for reappraisal.

That shifting perspective has renewed preservationists’ appreciation of such once-overlooked assets as the large murals painted by unemployed artists during the Depression, now known as WPA (Works Progress Administration) murals, located in schools and post offices across the country. These works languished as abstract art ascended after World War II, but renewed interest in researching and restoring these public art treasures has recently emerged.

Below-ground archaeological resources may also be protected by designating them as archaeological preserves, a strategy State Archaeologist Dr. Nicholas Bellantoni endorses: “Archaeological preserves are the best way to protect our archaeological sites and to educate the public about them.” Vandalism or damage to a site designated as an archaeological preserve is a crime, and offenders are subject to fines of up to $5,000. Currently there are 16 preserves: Hospital Rock (See “Hospital Rock,” March 2004) in Farmington received this protection in 2002. Close by, the Revolutionary War campsite in West Hartford is truly endangered by vandalism and housing development. Occupied for six days in 1789 by Revolutionary War General Israel Putnam’s division, this site is a very rare and, until recently, undisturbed Colonial military site. From an archaeological perspective, the site is fragile and most deserving of protection.

Throughout the state, outdoor sculptures are another important component of the cultural landscape, gracing our town greens, urban plazas, parks, and cemeteries. As part of a national initiative, the Smithsonian Institution’s nonprofit Museum of American Art and Heritage Preservation launched Save Outdoor Sculpture!; as part of this initiative, the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism researched and photographed more than 500 pieces of outdoor sculpture around the state. Two important works have received or are undergoing restoration: the century-old Corning Fountain in Bushnell Park in Hartford is picture perfect after its nine bronze figures and two stone basins were cleaned and waxed. The Civil War monument atop East Rock in New Haven (visible from I-91) is scaffolded and receiving care. Hundreds of feet above the New Haven coastline, the East Rock Monument is a $1 million project, part of a multi-year commitment to conservation made by the New Haven Parks Department.

In an example of preservation’s capacity to shine light on our history, Connecticut’s sculpture story turned out to be much bigger than expected. The sculpture inventory turned into a tutorial on Connecticut’s 19th- and 20th-century stone- and metal-casting industries. If it could be made — for a profit — out of stone or metal, it was produced by Connecticut mills and quarries. Branford granite and Portland brownstone were shipped nationwide. Bridgeport produced “white bronze” — really zinc alloy — cemetery markers and Civil War monuments. (The largest of these “zinkies” may be seen in Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford.) (See “Memorials to a Nation Preserved,” Spring 2011.)

A New Tool: Partnerships

With public policy in place for 40 years and many such successes racked up, it’s clear that the most crucial element for historic preservation success in the future is the development of active partnerships. In Connecticut, a wide range of governmental agencies, organizations, private sector interests, and individuals all play an important role. History connects many diverse interests, audiences, and constituencies.

As retired State Historic Preservation Officer John Shannahan accurately observes, “Preservation has become mainstream — not just little old ladies in tennis shoes saving old white houses. Historic preservation is a term you hear from mayors and other elected officials trying to make intelligent economic decisions.”

Thinking Outside the Box

The former G. Fox department store in Hartford has found new life as Capital Community College. photo: Patrick O’Sullivan

With partnerships in place, increasing sophistication and creativity are called for to find new uses for old buildings. One success story is the former G. Fox Department Stores. Linda Spencer has noted, “For much of the 20th century, G. Fox and other Main Street department stores made downtown Hartford a hub of retail activity. But in 1990, the G. Fox flagship store, still retaining much of its 1930 Art Deco detail, closed. Although acquired by the City of Hartford, the building remained largely unused, facing an uncertain future.”

But now, Spencer continued, “Thanks to the energy and vision of both the public and private sectors, the G. Fox building has been returned to productive use and maintains its pride of place in the city’s history. Reuse of this local landmark as the new home of Capital Community College, a retail mall, and offices exemplifies the economic and cultural value of historic preservation and its role in urban revitalization. The college portion of the building represents an investment by the state; a limited partnership using the federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives program is the developer of the retail and office space.”

Across the river, in the Manchester Main Street Historic District, the miniature castle building 1908 in the Military Gothic style for the Salvation Army as their Citadel had grown too small for the organization’s community service programs. Options included demolishing the historic building and replacing it with a new, much larger building. But the building was protected by the Connecticut Environmental Protection Act, which had expanded to cover not only natural resources but also historic ones. Manchester officials and experts from the Commission on Culture & Tourism met with representatives of the Salvation Army to discuss ways to incorporate the existing building with new construction to meet its needs. The happy result allowed this landmark to remain and the Salvation Army to stay on Manchester’s Main Street.

Lessons Learned

What lessons have we learned and what can we expect in the future? As John Shannahan noted, historic preservation has become a mainstream concept. From popular television shows and magazines to the availability of traditional building materials at do-it-yourself storesk the notion of historic preservation has sunk in. But we still experience tremendous losses. During the economic downturn of the 1990s our urban areas lost hundreds of buildings to abandonment and spot demolition, with losses rivaling the urban renewal era in sheer numbers. As the economy picks up, the landscape is gobbled up by ever-larger strip malls, big-box stores, and “McMansion” developments. Even the appeal of traditional Main Street shopping has been usurped by the new “lifestyle” shopping centers that mimic individual storefronts with parking at the curb.

“Tear downs”, (the practice of buying a property with a house, demolishing the existing building, and replacing it with a much larger one) are epidemic along Connecticut’s shoreline. This trend threatens to spill over to high-demand, inland towns such as Glastonbury and West Hartford. New Canaan’s stellar collection of internationally acclaimed Modern houses is unprotected and vulnerable.

What we have learned is that the job is never done. New threats and challenges continually crop up. Landmark buildings, historic districts, and archaeological sites saved by one generation often need to be saved again by the next. New building conservation practices, techniques, and materials constantly evolve. Legislation at all levels needs to be refined. Tax incentives and grant-in-aid programs must work to level the playing field for the retention of historic buildings.

“Those who think that preservation is about structures or places miss the point,” said Jennifer Aniskovich, executive director of the Commission on Culture & Tourism. “Preservation is about people — their stories and their lives. The structures give life to those people and help to tell their stories. Preservation connects people over decades and centuries. Advocates for preservation have always understood this — it’s not about sanctifying the old, but bringing the past into the light of the present.”

A Birthday Gift

Over the last 40 years the State of Connecticut has recognized the value of preserving the state’s rich and diverse heritage, even in the midst of dire budget circumstances. The Commission on Culture & Tourism was created in 2003 to merge the once-separate historic, arts, and tourism commissions with the film office. The move preserved each division’s role while encouraging new approaches and collaborations.

In July 2005, Governor M. Jodi Rell signed into law Public Act 228, An Act Concerning Farm Land Preservation, Land Protection, Affordable Housing and Historic Preservation. The bill dedicates an estimated $6 million for each of the programs named in the title — all essential to Connecticut’s quality of life. It is estimated that $5 million a year will be available for historic preservation programs and grants. Upon signing the bill, Governor Rell said, “…this is among the most worthy and visionary pieces of legislation we approved this year. In this one bill, we honor our state’s illustrious past and promote the well-being of future generations.”

Happy birthday, National Historic Preservation Act. You’re 40 and you’re fabulous. Let’s all work together to preserve the past for the future.

Mary M. Donohue has served as the survey and grants director of the Historic Preservation and Museum Division of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism, for more than two decades. She is an award-winning author and oversees the Commission’s Statewide Historic Resource Inventory, the state’s database of historic and architectural resources. Donohue co-wrote “The Conference State” in the Fall 2005 issue.