Re: Collections: Mastodon Frenzy

(c) Connecticut Explored, Winter 2007/2008

By Elizabeth Collins

By the 18th century, a massive, meat-eating elephant was haunting people’s dreams. Shawnee and Delaware tribal tales of meat-eating beasts hunted by giant men fed conclusions by key scientists, around 1770, that fragmentary fossil finds between 1705 and 1770 of nearly five-pound teeth and huge tusks belonged to an immense carnivore. We now theorize that the American Mastodon, an ancient relative of the elephant, roamed what is now the United States during the Ice Age in sizeable herds more than 10,000 years ago. While its larger relative, the Siberian Mammoth, lived in colder, northern climates, the American Mastodon preferred warmer, forested areas.

The mastodon fascinated many of the leaders of the American Revolution, including Thomas Jefferson, who used the animal as a symbol of American strength during the American Revolution and participated in the debate as scientists used the animal in support of the then-novel theory of extinction. Jefferson hoped Lewis and Clark would find a living specimen in the West, but eventually settled on sorting mastodon bones (from a Kentucky dig he’d sponsored) in the White House.

Charles Vincent Peale, a renowned artist and founder of one of America’s first natural history museums, conducted digs in the summer of 1801 near Newburgh, New York, in a quest for the first full skeleton. From the digs he reconstructed two skeletons. One was displayed at Peale’s Philadelphia museum in December 1801; the other was sent to Europe. The exhibits of the monstrous beast created an international frenzy and a craze for anything over-sized, such as “mammoth” bread or eggs. The animal, popularly known as a mammoth until renamed in the early 19th century, remained in the public imagination the most ferocious animal ever to roam the earth until dinosaur discoveries in the years from 1820 to 1840 pushed the mastodon, which was actually a plant eater, off that pedestal.

But in the summer of 1913 in Farmington, Connecticut, the discovery of a mastodon skeleton created a frenzy all over again, at least locally. At Hill-Stead, the 250 acre estate and farm of Alfred Pope, an industrialist and collector of fine art, workers creating a water trench during a drought discovered one of the most spectacular paleontological finds ever in New England. The 12, 000-year-old skeleton the workers unearthed was at the time the most complete mastodon skeleton ever found in New England.

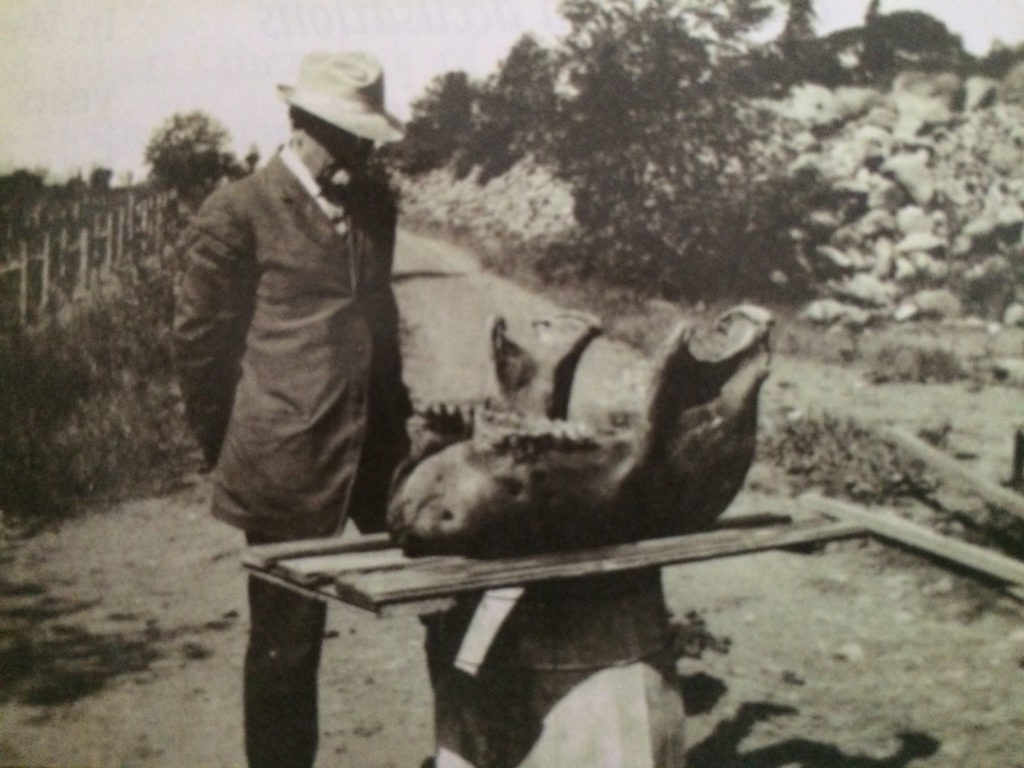

The commotion created by the August 26, 1913 discovery is documented in the archives of Hill-Stead Museum. Kept a secret for days while a Yale professor, Charles Schuchert, was located to verify the bones, the find was scooped by the Hartford Post on September 5, 1913. Two days later, 800 people flocked to the site to watch Peabody Museum specialists excavate the bones. Bold, front-page headlines in the Hartford Courant followed. The Associated Press carried the story to Colorado, Minnesota, and other states. Guards were posted and fences built around the site to hold back the 2,000 people who flocked to the dig in one week. Telegrams and mail flooded in to Hill-Stead.

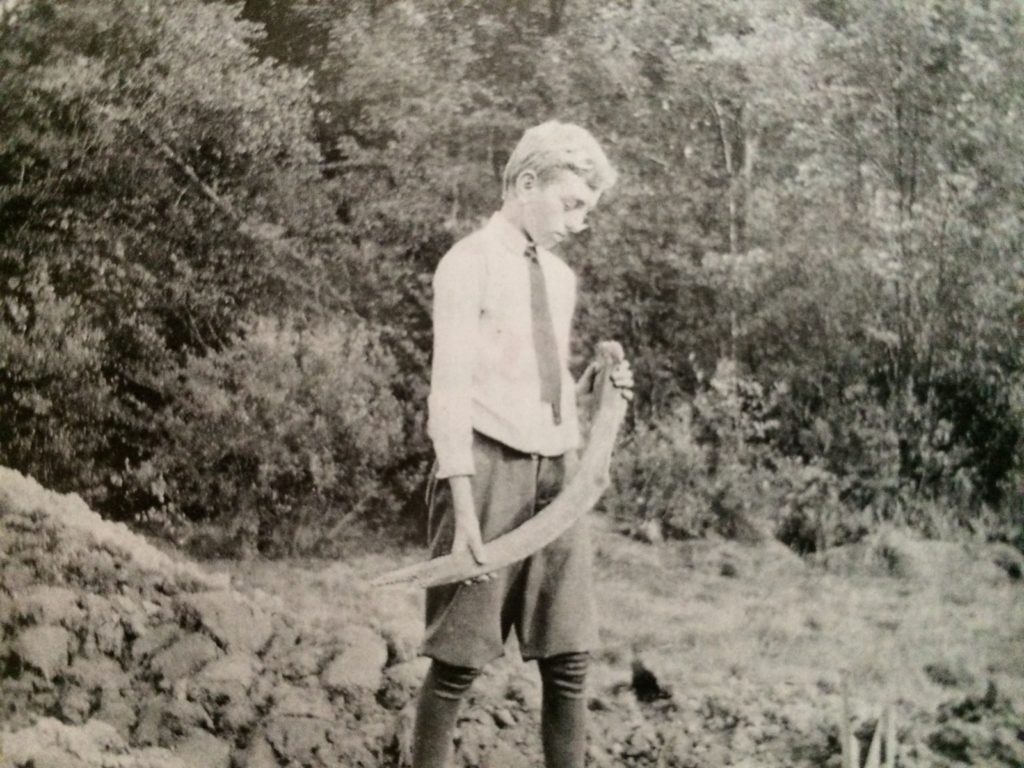

Frederick Cook, son of Hill-Stead’s superintendent Allen B. Cook, with mastodon bone, 1913. Hill-Stead Museum

The story was preserved by Allen B. Cook, the superintendent of Hill-Stead’s estate at the time, who felt the excitement of the event and created a large scrapbook of newspaper clippings and a second scrapbook of 37 photographs he took of the dig. Donated to the museum by his daughter Charlotte Cook Collins and grandson William B. Cook in September 1998 and March 2000, the documentation also contains letters, telegrams, articles, and statistics on the bones. The collection can be seen by appointment at Hill-Stead Museum.

In 1971 the bones were donated to the State of Connecticut. Between 1977 and 1989 a full display of the bones occurred at the Institute for American Indian Studies in Washington, Connecticut. Some of the bones have also been displayed at the Yale Peabody Museum in New Haven. The Connecticut State Museum of Natural History in Storrs, which currently has the bones, recently opened a new exhibit area featuring the femur bone of Hill-Stead’s famous mastodon.

The Hill-Stead Museum, a National Historic Landmark located at 35 Mountain Road in Farmington, is open Tuesday through Sunday 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. (last tour leaves at 3 p.m.) in the winter months. Call (860) 677-4787 or visit www.hillstead.org. The Connecticut State Museum of Natural History, located on the University of Connecticut campus in Storrs, is open Tuesday through Saturday 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Call (860) 486-4460 or visit www.mnh.uconn.edu.