(c) Connecticut Explored, Spring 2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Industrial America, with its modern marvels of railroad, telephone, and electricity, and technologically innovative Hartford in particular, fascinated and greatly influenced both Samuel Clemens — the man, and Mark Twain — the writer. Not only did he make abundant literary references to technology in his writing, he invented and patented three diverse products: an elastic garment strap, a self-pasting scrapbook, and a memory game. In addition, Twain financed others’ inventions and was fascinated by innovation — whether big or small. In a congratulatory letter to Willard White, inventor of “White’s Portable Folding Fly and Musketo Net Frame,” he expressed his joy over the device.

Mr. White, – Dear Sir:

There is nothing that a just and right feeling man rejoices in more than to see a mosquito imposed on and put down, and brow-beaten and aggravated, and this ingenious contrivance will do it. And it is a rare thing to worry a fly with, too. A fly will stand off and curse this invention till language utterly fails him. I have seen them do it hundreds of times. I like to dine in the air on the porch in summer, and so I would not be without this portable net for anything; when you have got it hoisted, the flies have to wait for the second table. We shall see the summer day come when we shall all sit under our nets in church and slumber peacefully, while the discomfited flies club together and take it out of the minister.

Twain eagerly embraced technology in his work (The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was the first American book submitted to a publisher in typed manuscript) and in his everyday life. Soon after Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in 1876, Twain had one installed in his house in Hartford and it quickly became the target of his ire. In a letter to Bell’s father-in-law, Gardiner G. Hubbard (whom he dubbed “The Father-in-law of the Telephone”), Twain lamented the poor service, absence of nightly telephone service, and worse, the shocking rudeness of the operators who cut him off while he was swearing into the phone.

In May 1884, Twain bought a popular contraption that literally drove him to the ground. He and Rev. Joseph Twichell purchased the locally manufactured Columbia high-wheeled bicycles and took riding lessons together. As Twain wrote in his 1884 essay “Taming the Bicycle,”[1]

I thought the matter over, and concluded I could do it. So I went and bought a barrel of Pond’s extract and a bicycle. The Expert came home with me to instruct me. We chose the back yard, for the sake of privacy, and went to work… . The Expert explained the thing’s points briefly, then he got on its back and rode around a little, to show me how easy it was to do. He said that the dismounting was perhaps the hardest thing to learn, and so we would leave that to the last. But he was in error there. He found, to his surprise and joy, that all he needed to do was to get me on to the machine and stand out of the way; I could get off, myself. Although I was wholly inexperienced, I dismounted in the best time on record. He was on that side, shoving up the machine; we all came down with a crash, he at the bottom, I next, and the machine on top.

We examined the machine, but it was not in the least injured. This was hardly believable. Yet the Expert assured me that it was true; in fact, the examination proved it. I was partly to realize, then, how admirably these things are constructed… .

“…Get a bicycle,” Twain concluded. “You will not regret it, if you live.” [See “Columbia Bicycles: The Vehicle of Healthful Happiness,” Spring 2003, and “The Miracle on Capital Avenue,” May/Jun/Jul 2004.]

TWAIN’S INVENTIONS

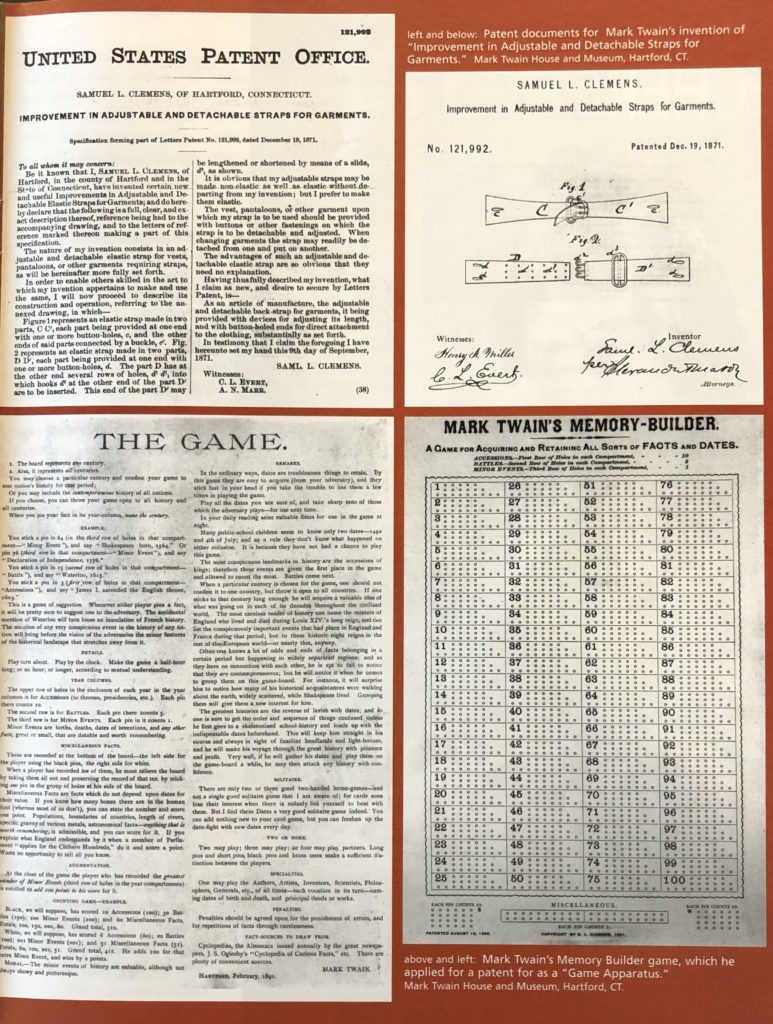

top right and left: Patent documents for Mark Twain’s invention of “Improvements in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments.” bottom left and right: Mark Twain’s Memory Builder game, which he applied for a patent for as a “Game Apparatus.” Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford

“Modesty died when clothes were born,” Twain opined wryly. Yet, despite his disdain of Gilded Age pomposity in clothing, he invented a device to hold garments in place at the waist. On September 9, 1871, Twain filed a patent for “Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments.” The contraption was an elastic strap that could be attached to the back of vests, underpants, and ladies’ garments – including corsets – with buttons and other fastenings on which the strap was adjustable and detachable. His intent was to do away with suspenders, considered uncomfortable.[2] However, Henry C. Lockwood of Baltimore, Maryland, had invented an identical device and filed for a patent at almost the same time. The Patent Office called for an “interference,” a legal procedure conducted to establish the first inventor from among the applicants. After filing a “preliminary statement,” the applicants brought witnesses and put for the facts of their case, arguing as to why they should be the one awarded the patent. Twain, in his inimitable tongue-in-cheek élan, presented his side of the “story” to the Patent Office.[3]

The idea of contriving an improvised strap is old with me; but the actual accomplishment of the idea is no older than the 13th of August last (to the best of my memory). This remark is added after comparing notes with my brother.

For four or five years I turned the idea of such a contrivance over in my mind at times, without a successful conclusion; but on the 13th of August last, as I lay in bed, I thought of it again, & then I said I would ease my mind and invent that strap before I got up — probably the only prophecy I ever made that was worth its face.

An elastic strap suggested itself & I got up satisfied. While I dressed, it occurred to me that in order to be efficient, the strap must be adjustable & detachable, when the wearer did not wish it to be permanent. So I devised the plan of having two or three buttonholes in each end of the strap, & buttoning it to the garment — whereby it could be shortened or removed at pleasure. So I sat down and drew the first of the accompanying diagrams (they are the original ones).

While washing (these details seem a little trivial, I grant, but they are history & therefore in some degree respect-worthy), it occurred to me that the strap would do for pantaloons also, & I drew diagram No. 2.

After breakfast I called on my brother, Orion Clemens, the editor of the ‘American Publisher,’ showed him my diagrams and explained them, & asked him to note the date & and the circumstances in his note-book for future reference. (I shall get that note of his and enclose it, so that it may make a part of this sworn evidence.) While talking with him it occurred to me that this invention would apply to ladies’ stays, & I then sketched diagram No. 3.

In succeeding days I devised the applying of the strap to shirts, drawers, &c., & when about to repair to Washington to apply for a patent, was peremptorily called home by sickness in my family. The moment I could be spared, however, I went to Washington & made application — about the 10th or the 12th of September, ult., I think. I believe these comprise all the facts in the case.

Twain was awarded patent number 121,992 for his “Improvements in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments” on December 19, 1871. Unfortunately, the device never went beyond the drawing board, but Twain was undaunted. Two years later on June 24, 1873, he patented a self-pasting scrapbook (patent number 140,245).

An avid scrapbook keeper, Twain’s tribulations with the hard glue then in use drove him to frequent bouts of profanity. In a letter to friend Daniel Slote, an old Quaker City fellow traveler whose company manufactured the scrapbook, he wrote: “I have invented a scrap book to economize the profanity of the country.” Twain’s invention came with pages gummed with thin strips of glue in columns, ready to be moistened and passed with scraps — making the processes quick and easy. According to an 1885 notice in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Twain had made $50,000 from the scrapbook in 12 years. By 1901 it was commercially available in 57 types. An advertisement place by Slote, Woodman, & Co., New York, in Harper’s Bazaar, stated the price as varying between $1.25 and $3.50 apiece. According to Twain’s biographer Albert Bigelow Paine, “It was well enough for a book that did not contain a single word that critics could praise or condemn.”[4] In a letter to his brother Orion Clemens, Twain wrote “But what I wish to put on record now, is my new invention — hence this note, which you will preserve. It is this — a self-pasting scrapbook — good enough idea if some juggling tailor does not come along and ante-date me a couple of months, as in the case of the elastic vest strap.”

An advertisement for Mark Twain’s self-pasting scrapbook. The scrapbook was Twain’s only invention to earn money. Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford

Twain’s final patented invention was a trivia history game about European monarchs. What started as an outdoor educational activity for his daughters Suzy, Clara, and Jean to remember historical dates quickly turned into a marketable proposition with cards and a board, played indoors. In a letter to Twichell, Twain claimed he spent eight hours in the sun measuring out the reigns of kings and queens in the driveway and grounds of his house with a yardstick. He gave each monarch’s reign one foot of space to the year, with stakes driven to the ground to mark it.[5] Distances between each stick indicated the duration of each reign — long or short. “You can mark the sharp difference in the length of reigns by the varying distances of the stakes apart. You can see Richard II., two feet; Oliver Cromwell, two feet: James II., three feet, and so on-… .”

Twain was granted patent number 324,535 for his “Game Apparatus” on August 18, 1885, which later became the Memory Game. He immediately set about making ambitious plans for manufacturing and marketing his invention. Wrote Paine, “He would prepare a book to accompany these games. Each game would contain one thousand facts, while the book would contain eight thousand; it would be a veritable encyclopedia. He would organize clubs throughout the United States for playing the game; prizes were to be given” Unfortunately, these plans did not materialize. Little is known of the fate of the indoor version — played on a board with stakes replaced by holes marking the historical dates — except that it was never a commercial success.

INVESTING IN OTHERS’ INVENTIONS

Throughout his life, Twain financed various inventions and money-making schemes that, lamentable, led to his financial ruin. By 1891, he had lost close to $300,000 in the infamous Paige Compositor designed by James Paige. Never one to give up, he left Hartford, traveled around the world on a lecture tour to earn money, and returned to the United States in 1900, debt free and a global celebrity. Ironically, despite his patents and his speculations, in the end Samuel Clemens’s greatest and most brilliant invention was Mark Twain[6] — universally endearing, time-tested and enduring, and certainly the most profitable.

Sujata Srinivasan is a freelance journalist and editor, whose writing has appeared in The Hartford Courant, Northeast magazine, Hartford Magazine, and other publications in the U.S. and India. She is also a museum teacher for The Mark Twain House & Museum. The author is grateful to the Mark Twain House & Museum, especially archivist Margaret Moore, for assistance with this article.

Explore!

Read more about Mark Twain’s Scrap-Book in the Winter 2020/2021 issue

Read more stories about Mark Twain and other Notable Connecticans, and other products made and invented in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

LISTEN

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 82: Writing with Scissors: Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and American Scrapbooks

Footnotes:

[1] Mark Twain was dissatisfied with the essay and put it aside. It was published posthumously in “What is Man? and Other Essays” in 1917.

[2] United States Patent and Trademark Office.

[3] An article published in The New York Times, March 12, 1939, www.twainquotes.com (November 16, 2004).

[4] C. Canistro, D. Dudley, L. Hadad, D. Patrick, ‘The Writer Confronts the Machine,’ March 19, 1980, The Mark Twain House & Museum collection. The authors quote Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain, A Biography: The Personal and Literary Life of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, ch. 15.

[5] Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain, A Biography: The Personal and Literary Life of Samuel Langhorne Clemens, 3 volumes, (New York: Harper, 1912).

[6] On February 3, 1863 the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise published a letter from Carson City, Nevada, that Clemens signed Mark Twain.