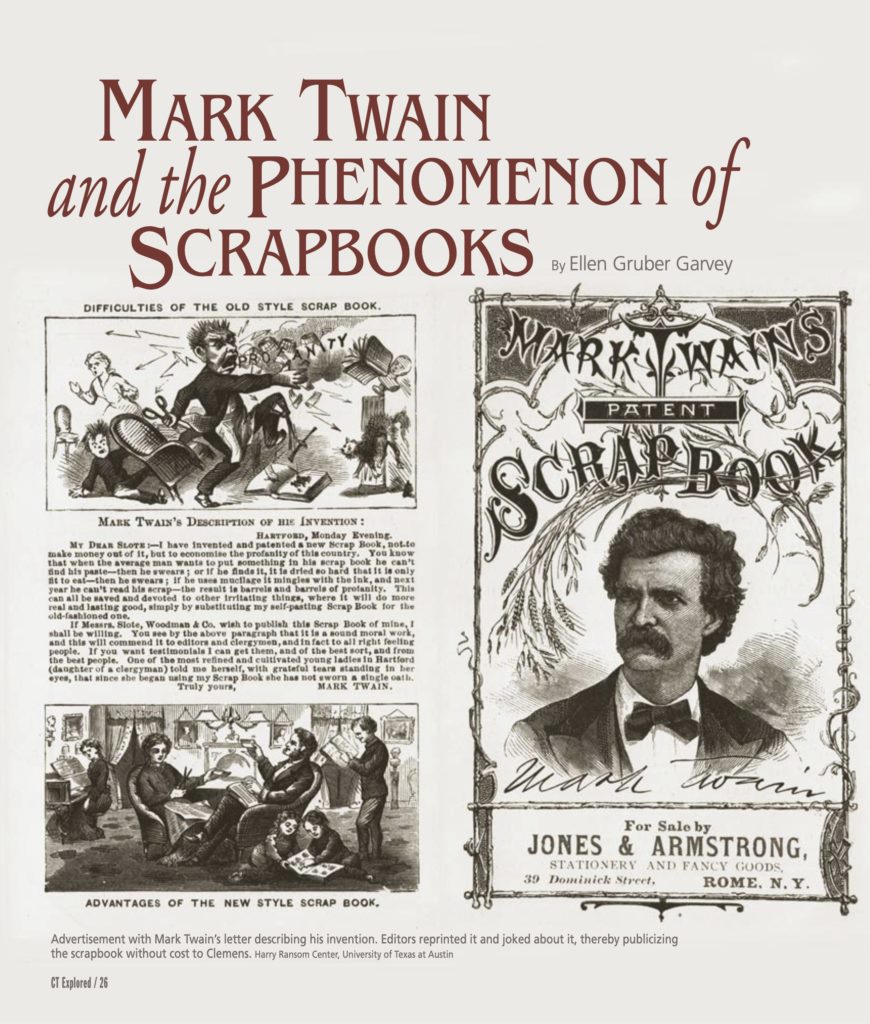

Advertisement with Mark Twain’s letter describing his invention. Editors reprinted it and joked about it, thereby publicizing the scrapbook without cost to Clemens. Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

By Ellen Gruber Garvey

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2020-2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Back in Mark Twain and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s time (the late 19th century) American writers had a problem. If they wrote something appealing and it was published in a particular newspaper, other newspapers and magazines would freely reprint it without crediting the author—unless the writer had become well-known and his or her name helped sell papers. The humorist Bill Nye, who sometimes lectured with Mark Twain, protested bitterly against editors who snipped off bylines. They were like thieves stealing a man’s only shirt from the clothesline while he is “in bed and therefore helpless,” Nye wrote in “The Editorial Shears,” an article gathering comments about reprinting in the Austin, Texas newspaper Texas Siftings, February 27, 1886. What if you were a young writer starting out? How could you keep editors from stealing your shirt?

Samuel Clemens used his catchy pen name Mark Twain strategically to hold onto his intellectual property, in the face of rapacious, credit-free reprinting, by inserting Mark as a character into his early stories. He went on to take revenge on those avid reprinters with an unlikely weapon: a scrapbook he invented. He kept scrapbooks, as did thousands of others, including some of his neighbors at Nook Farm in Hartford, where he lived across the lawn from Harriet Beecher Stowe and her family. Such scrapbooks are a rich source for historians, as they sometimes are the only extant permanent record of information from newspapers and magazines that long ago went out with the trash, as I discuss in Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford University Press, 2013).

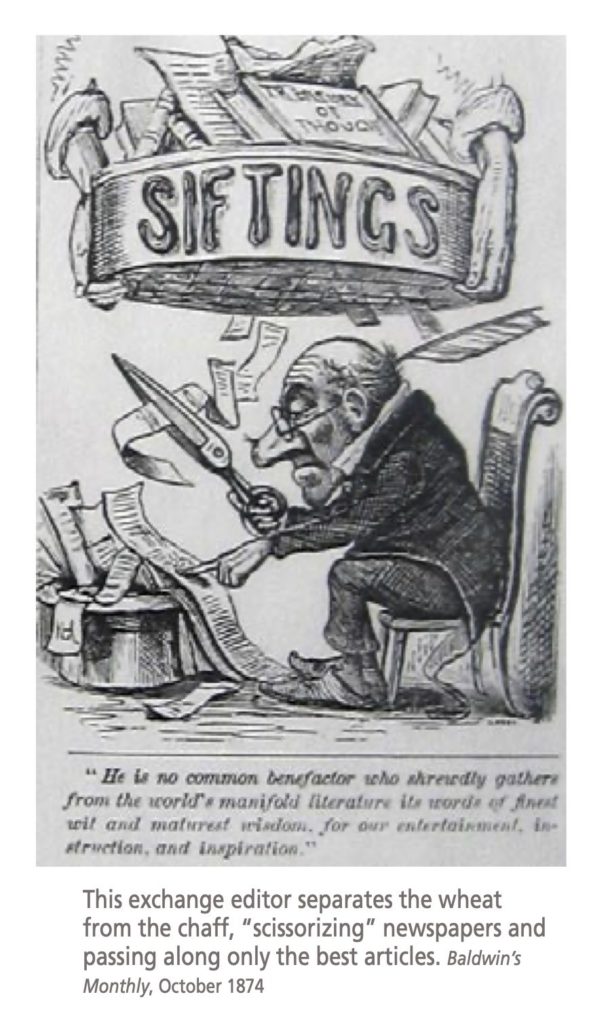

This exchange editor separates the wheat from the chaff, “scissorizing” newspapers and passing along only the best articles. Baldwin’s Monthly, October 1874

Despite Nye’s complaint, in the late 19th century editors did not think there was anything wrong with filling their columns with material they freely borrowed from other papers. The U.S. government even encouraged them, offering publishers free postage to mail newspapers to other newspapers, via a system known as exchanges. Larger newspapers had specialized scissors-wielding exchange editors, who scanned piles of papers prowling for material to print. Contrary to Nye in “The Editorial Shears,” Thomas Weaver, editor of the Hartford Post, argued that exchanges improved newspapers: “The scissors, well used, can give the product of five hundred brains in one newspaper, and one brain plus five hundred is a great deal better than when it stands alone on its own originality, no matter how great that originality may be.” Before aggregated news services like the Associated Press gathered and redistributed news, the exchange system created a nationwide network of information. It was a sign of acclaim for a newspaper when its works were “scissorized,” as the practice was sometimes called, and reprinted widely.

Literary authors such as Twain could benefit from exchanges when they were starting out. While authors typically were paid only for the first use of a story or poem, a reprinted piece could attract attention around the country—if the author’s name remained attached to the work. Then, reprinting could make them famous and lead to higher future fees or lucrative lecture engagements, as I discovered in my research for Writing with Scissors.

Samuel Clemens made sure that no matter how often his stories were reprinted, they retained the name Mark Twain—by writing in the character of Mark Twain. He used this device in some of his earliest published work, for the Territorial Enterprise in Virginia City, in the Nevada territory. Pretty soon he fleshed out Mark’s character in the stories; for example, the conniving flatterers who address Mark Twain in “Letter from Carson City: Concerning Notaries,” which appeared in the Enterprise on February 9, 1864. “Why darn it, Mark, how well you’re looking! Thunder! It’s been an age since I saw you. Turn around and let’s look at you good. Gad, it’s the same old Mark!,” one character in the story said. Even the most active scissors could not clip off a name in the middle of a story.

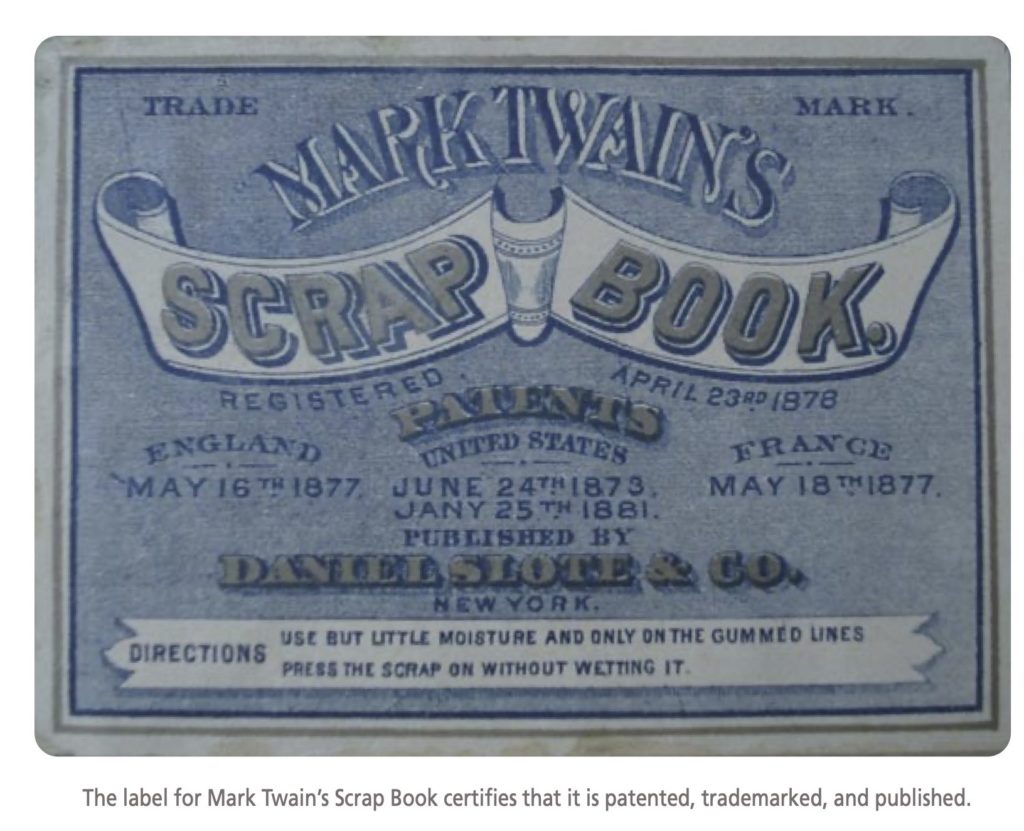

Later, Clemens experimented with ways to keep hold of ownership of his writing via trademark and patent law. Though his battles to protect his intellectual property often failed, he paradoxically succeeded in protecting a book he didn’t write: his invention, Mark Twain’s Scrap Book, which went by various names, including Mark Twain’s Self-Pasting Scrap Book. He could protect this blank book with pre-gummed pages with patent and trademark law, both of which were more powerful than the copyrights that covered the books he wrote. Beginning in 1877, he made money more reliably from the sale of the scrapbook than he did from some of his writings—especially when they were pirated and reprinted in book form without recompense, as Barbara Schmidt learned in her work on the sticky-fingered Belford and Clarke publishing firm, “A Closer Look at the Lives of True Williams and Alexander Belford” (Fourth International Conference on the State of Mark Twain Studies, 2001). Claims of how much he received from the sale of his scrapbooks varied considerably. Was it $1,800 to $2,000 per year? Or $12,000 at first, then dwindling, as Samuel Charles Webster reports in Mark Twain, Business Man (Little, Brown and Company, 1946).

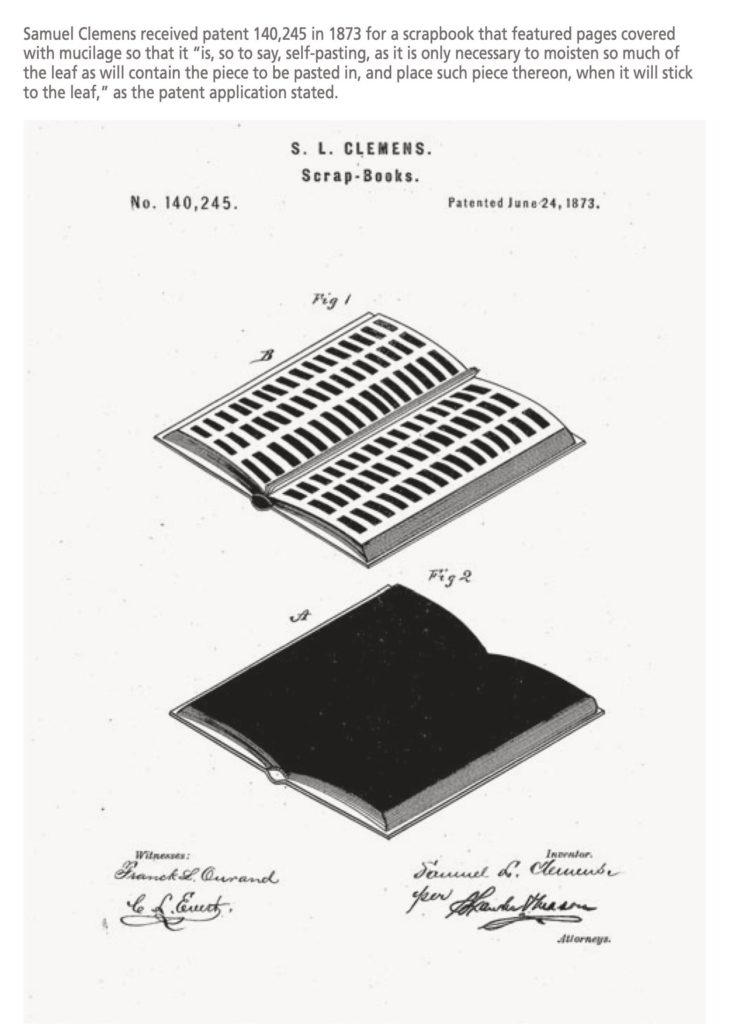

Clemens thought of his scrapbook as both a convenient, portable invention and a book like others he had written. The label inside identifies it as “published,” rather than manufactured or printed, by his friend Daniel Slote’s stationery firm. By 1902 the scrapbooks even included a dated title page. They sold for anywhere from 40 cents to $5. He was awarded a patent for his Scrap Book in 1873. [See also “Mark Twain, Inventor!,” Spring 2005.]

When Clemens, writing as Mark Twain, sent out a letter to the press promoting his scrapbook, he finally got some payback from the editors who pillaged and reprinted his work without paying him. The letter (really an advertisement) extolled the virtues of the scrapbook, using Twain’s signature wit. In it, Twain explained that his scrapbook would “economize the profanity of this country” by reducing the user’s frustration with conventional scrapbooks, such as when the glue could not be found or was dried out. Mark Twain’s Scrap Book was, therefore, a “sound moral work.”

Samuel Clemens received patent 140,245 in 1873 for a scrapbook that featured pages covered with mucilage so that it “is, so to say, self-pasting, as it is only necessary to moisten so much of the leaf as will contain the piece to be pasted in, and place such piece thereon, when it will stick to the leaf,” as the patent application stated.

The ad was framed as a letter from Twain to Daniel Slote, and its intimate tone made it easy for each newspaper’s editor to appropriate. Newspapers refashioned it to print among miscellaneous news items. Some editors added commentary, and then Slote quoted them as blurbs in other ads, such as one from the Danbury (Connecticut) News, which had reported that the scrapbook was “a valuable book for purifying the domestic atmosphere, and . . . contains nothing that the most fastidious person could object to, and is, to be frank and manly, the best thing of any age – mucilage particularly.” The Norristown(Pennsylvania) Herald announced, “No library is complete without a copy of the Bible, Shakespeare, and Mark Twain’s Scrap-Book.” Magazines even jokingly reviewed it as though it were an autobiography. The free advertising Clemens received for his scrapbook finally gave him revenge on the exchange system: The newspapers were not paying him for his work, but they also were not charging him for an ad.

Clemens used scrapbooks before he invented a handier version. He used them, and delegated others to use them, to preserve his published stories and organize them for future use. A good example is his stories for the Alta Californianewspaper. As Clemens traveled the globe in 1867, writing about his adventures for the Alta California, his sister Pamela Clemens Moffett in St. Louis subscribed to the newspaper. At Twain’s request, she cut and pasted his articles into a scrapbook (now in the Bancroft Library archives at the University of California, Berkeley) so that they were ready for him to edit and later rework into The Innocents Abroad, published in 1869.

Scrapbooks allowed other writers as well to track their work published in newspapers and magazines. Due to the ephemeral nature of newspapers and magazines, researchers who stumble on such scrapbooks today may find the only copies of an author’s stories or articles that are the only evidence linking authors to work they wrote under different names. Authors’ and speakers’ scrapbooks also reveal their work processes, such as how they collected news items they might later draw upon in speeches and writings. Clemens had his secretary cut and paste records of London’s Tichborne Trial, the sensational 1873 trial of a butcher who claimed to be the heir to an English estate. The clippings filled six scrapbooks, though Clemens later wrote that the story was too improbable to be useful to a “fiction artist” and didn’t end up writing about it.

The suffragist writer and speaker Lillie Devereux Blake, who spent most of her childhood and youth in New Haven, kept a scrapbook in the early 1870s that she titled “Articles about Woman’s Position and Interesting Items,” pasted into an old daily journal. It’s now in the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College. It included stories of “everyday heroism” and others about brutality against women. These stories were retold in her speeches and writings about laws that allowed men to beat their wives.

In my research for Writing with Scissors I found that thousands and more likely tens of thousands of people all over the country kept scrapbooks to preserve a record of their reading, events important to them in the news, and sometimes their own appearances in the press. Some of those scrapbooks have made their way into libraries and museums. Yale University’s Beinecke Library recently bought nine large scrapbooks of newspaper clippings created by the family of Frederick Douglass to document his career. David Blight, author of the recent Pulitzer Prize-winning biography Frederick Douglas: Prophet of Freedom (Simon & Schuster, 2020), found rare clippings containing important new information about Douglass’s later life not available elsewhere.

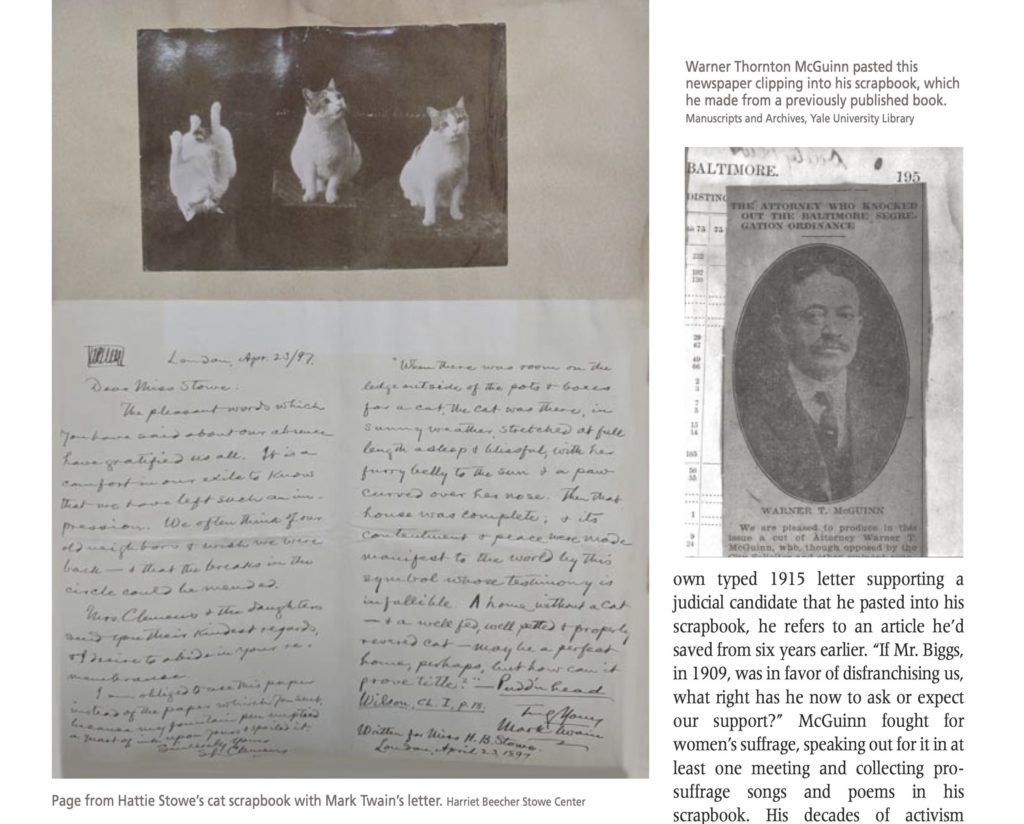

(left) Page from Hattie Stowe’s cat scrapbook with Mark Twain’s letter. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center; (right) Warner Thornton McGuinn pasted this newspaper clipping into his scrapbook, which he made from a previously published book. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library

Many people kept scrapbooks simply to save news items that interested them. They were a kind of filing system. Yale also owns the scrapbook of Warner Thornton McGuinn, an African American man and an 1887 Yale Law School graduate. He was working his way through law school when Samuel Clemens met him in 1885 and offered to subsidize his last year and a half of studies. McGuinn began his scrapbook around 1901. Mark Twain’s Scrap Book was rarer by then, and McGuinn did not use one. Instead, like many other scrapbook users, he re-used an old book. Columns of vital statistics peep out from behind his clippings. His scrapbook tracks his law career in Baltimore, where he moved in 1891, and instances in which he appeared in the newspaper, such as when he gave the main oration at a memorial service for Frederick Douglass in 1905.

In an era when newspapers rarely published indexes and libraries did not always save newspapers, scrapbooks preserved political records. Scrapbooks allowed their makers to create records of fast-changing events that had not yet appeared in history books or situations in marginalized communities whose news and history was not likely to appear in books. For instance, McGuinn collected news items about the suppression of Black voting. His clippings from the white press stored up ammunition on politicians who supported any of the three early 20th-century bills aimed at stripping the vote from African Americans in Maryland. In a copy of his own typed 1915 letter supporting a judicial candidate that he pasted into his scrapbook, he refers to an article he’d saved from six years earlier. “If Mr. Biggs, in 1909, was in favor of disfranchising us, what right has he now to ask or expect our support?” McGuinn fought for women’s suffrage, speaking out for it in at least one meeting and collecting pro-suffrage songs and poems in his scrapbook. His decades of activism stretched farther into the future. He mentored Thurgood Marshall, who said McGuinn should have been a judge.

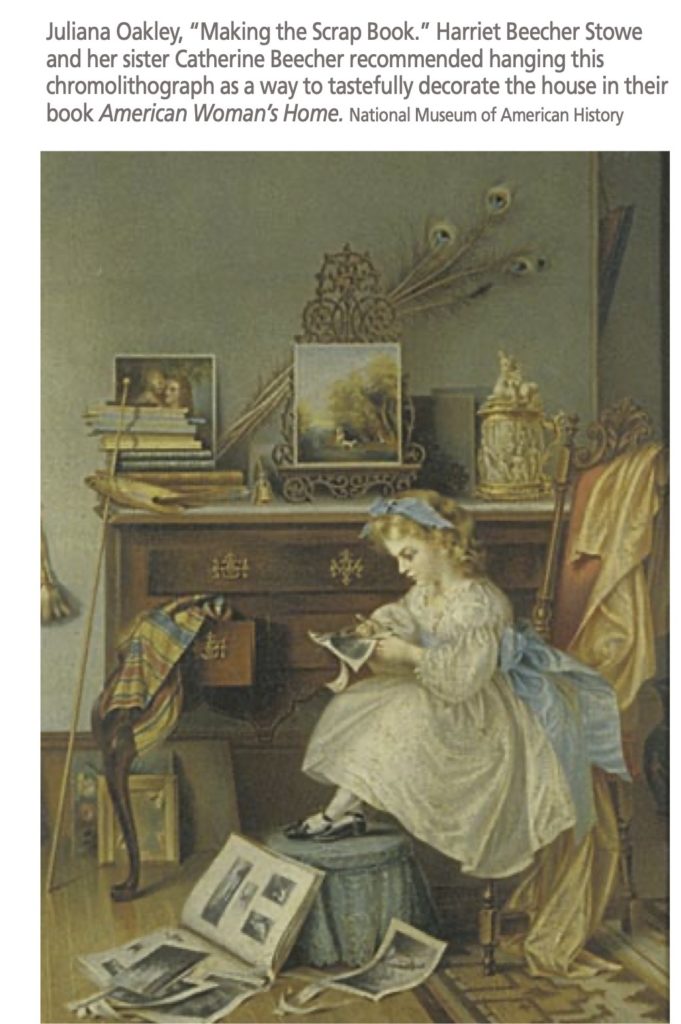

Mark Twain wasn’t the only Nook Farm resident interested in scrapbooks. Harriet Beecher Stowe and Catherine E. Beecher’s 1869 compendium of advice on household matters, The American Woman’s Home, is full of firm opinions about carpets and better ways to organize the kitchen. It recommends hanging a print of “Miss Oakley’s charming little cabinet picture of ‘The Little Scrap-Book Maker.’” This is surely American artist Juliana Oakley’s “Making the Scrap Book,” available as a chromolithograph featuring a small girl surrounded by other chromos, cutting out images for the kind of picture scrapbook more often made by children.

Stowe’s daughter Hattie, then in her 50s, made a scrapbook beginning in the 1880s and now in the archives of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. Her scrapbook is focused on all things cat-related. She clipped newspaper items about cats, her mother’s handwritten poem to her about a cat, and a note her mother had received from a fan about how similar the fan’s cat “Silver” was to “Calvin,” a cat Stowe had described in an essay. The growing popularity of greeting cards yielded many cards featuring images of cats. Cats won out against personal connections, and Hattie pasted them message-side down to display the cat pictures.

Harriet Beecher Stowe often sent correspondents lines or sayings they’d solicited for their albums. Less than a year after her mother’s death in 1896, Hattie asked Clemens to copy out a passage praising cats from Pudd’nhead Wilson, which she pasted in her scrapbook. Her request became the occasion for an affectionate exchange in 1897 in which Clemens responded to Stowe’s reflection on her losses. He wrote from London that he and his wife and daughters wished they could be back in Hartford, “and the breaks in the circle could be mended.”

Hattie’s brother Charles Stowe probably made the scrapbook that is now in the Stowe family papers at the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University. Pasted into a Mark Twain’s Scrap Book, its clippings begin around 1886 and include obituary tributes to Stowe and items about Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

William Henry Dorsey of Philadelphia made 400 scrapbooks, one of which was about Harriet Beecher Stowe and covers much the same period as Charles Stowe’s scrapbook. Literary scholar Barbara Hochman has observed in Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Reading Revolution (UMass Press, 2011) that Stowe and Dorsey—one white and one African American—sometimes collected the same items. But Dorsey’s selections show that he thought of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as akin to a history. He had grown up as the son of an escaped slave, and the choices he made offer tantalizing glimpses into what reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin meant to him. He clipped articles about various people said to be the originals for characters in the book and focused on George Harris, not Tom, as the book’s hero. He saved clippings that acknowledge that white Southerners continued to hate Stowe and compiled evidence of the continuing vicious defense of slavery, such as one story headlined “Glad of Mrs. Stowe’s Death” and one by a Confederate general making the familiar Southern complaint that Stowe gave a false impression of the South. Charles Stowe did not collect stories like these.

Scrapbooks allowed their makers to save the scraps and snippets that would otherwise have gone into the kindling pile and make them into a new, re-readable whole. Mark Twain’s Scrap Book allowed users to moisten the page and stick items down on the fly, even while traveling, without the messy trouble of glue pot and brushes. Most people continued to reuse old books or obsolete ledgers. If they cursed a blue streak in frustration with their gluing, that’s not part of the record they left us. They left, instead, in historical societies and libraries and attics all over the country, a rich record of their reading and obsessions.

Ellen Gruber Garvey is an English professor at New Jersey City University and author of Writing with Scissors: American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Explore!

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 82: “Writing with Scissors”

Listen to Ellen Gruber Garvey’s lecture at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in November 2019.

The Mark Twain House & Museum

385 Farmington Avenue, Hartford

MarkTwainHouse.org, 860-247-0998

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

77 Forest Street, Hartford

HarrietBeecherStoweCenter.org; 860-522-9258

Subscribe to receive every issue!