(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2003

The closest thing to a Hollywood walk of fame Hartford has is the entrance to the city’s public library. As patrons approach the library’s main door they see a group of stars embedded in the concrete pavement naming Hartfordians known for their contributions to politics, science, literature, and the arts. One of these stars is dedicated to someone dear to Puerto Ricans in the city: María Sánchez. In Frog Hollow, an elementary school bears Sánchez’s name. During the last years of her life she was known as the godmother of the Puerto Rican community in the city.

Who was María Sánchez and how did she come to deserve these honors? In many ways, her story is the story of the Puerto Rican community in Hartford. Like most Puerto Ricans coming to the city in the 1950s, she was of humble origins. Her journey from the town of Comerío to the Insurance City was prompted by the same political and economic forces that drove tens of thousands of Puerto Ricans from the warmth of the Caribbean to frigid New England. The colonial acquisition of Puerto Rico by the United States in 1898 established the links that made American cities points of destination for Puerto Rican migrants, and the restructuring of Puerto Rico’s economy by American capitalists made the move to these destinations necessary. Sánchez was not thinking about colonialism and capitalism when she left Puerto Rico. More likely, her move was triggered by personal considerations but her case is emblematic. And once in Hartford, a seemingly nonpolitical decision quickly led to a lifetime of political activity.

After arriving in Hartford in 1954, Sánchez was introduced to politics by Olga Mele, another Puerto Rican pioneer who had relocated in Hartford in 1941. This was part of a concerted effort to promote Puerto Rican political participation. As Mele recalled to me in 1992: “We began registering voters in 1950… I helped the Americanos get the Puerto Rican vote. I registered María in 1955, I believe, and her husband and her whole family.” It was with Mele that Sánchez participated in an act of personal advocacy that was by extension an action on behalf of Puerto Ricans in the city. “María Sánchez and I [complained],” said Mele, “that we couldn’t confess because there were no Spanish priests [at St. Peter’s Church]. We used to pay priests to come from New York… so the church saw that there was a need and in 1955 [the Spanish-speaking]Father Cooney was appointed… and he was put in charge of the Hispanics.” In 1959 Sánchez, Mele, and others at Sacred Heart Church, demanded the removal of Father Joseph Otto from the parish for his refusal to move the Spanish-language mass out of the church basement. The Chancery met the demands of the petitioners. Because this action involved group mobilization and conflict it can be considered political. As such, it is probably the first of the many empowering experiences that María Sánchez participated in during her life in Hartford.

Conflict and competition within political parties have a way of forcing party elites to pay special attention to emerging constituencies. In Hartford this was the case in 1957 when James Kinsella used Puerto Ricans as bullet votes (votes targeted for a specific candidate) in his attempt to become mayor. The Puerto Rican community was again the focal point in 1965 during George Ritter’s campaign for a seat on the city council. During that contest the Democratic Party paid special attention to María Sánchez. Nicholas Carbone, one of Hartford’s political leaders during the 1970s, approached Sánchez and brought her into the effort. “We were looking to win an election, and every vote was important,” he recalled in 1991. Also in 1965, fourteen Puerto Ricans met at the North End Democratic Club on Barbour Street to organize the Puerto Rican Democrats of Hartford. María Sánchez was elected treasurer of this pioneering group.

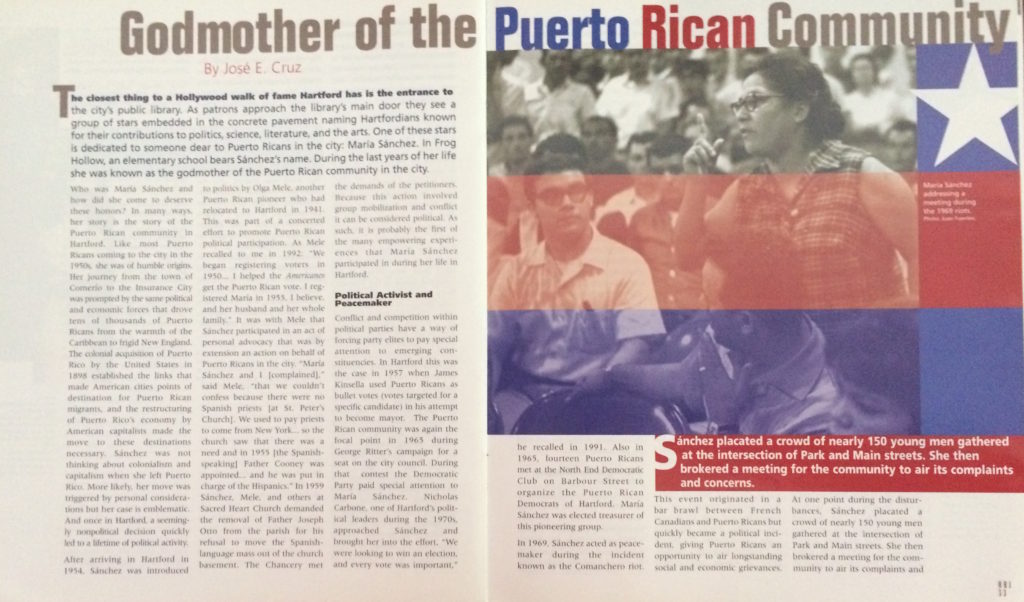

In 1969, Sánchez acted as peacemaker during the incident known as the Comanchero riot. This event originated in a bar brawl between French Canadians and Puerto Ricans but quickly became a political incident, giving Puerto Ricans an opportunity to air longstanding social and economic grievances. At one point during the disturbances, Sánchez placated a crowd of nearly 150 young men gathered at the intersection of Park and Main streets. She then brokered a meeting for the community to air its complaints and concerns. Participants included city councilman Carbone and City Manager Elisha Freedman. During the meeting, held at the South Green Multiservice Center on Main Street, Puerto Ricans told stories of police brutality, of being arrested in disproportionate numbers and without cause, and of being mistreated even when they tried to assist the police. Another councilman present, George Athanson, urged Puerto Ricans to run a candidate for city council. Many thought this was a good idea, but it did not happen for some time.

During the riot, The Hartford Foundation for Public Giving announced that it would donate $78,640 to the Greater Hartford Community Council to address Puerto Rican needs. After the riot, the local press became more accessible to Puerto Ricans and was eager to help rebuild the community’s image. The community itself became more unified. Groups such as the Spanish Action Coalition, an advocacy network that Sánchez helped organize in 1967, Puerto Rican Action for Progress, the Spanish American Association, and the Comerieños Ausentes, among others, became more visible and energized. Throughout the process, Sánchez was a key actor. Recalling Sánchez’s work during this crisis, Juan “Johnny” Castillo (the father of former councilwoman Yolanda Castillo) told me in 1992: “María Sánchez did a lot to stop the rioting, to maintain communication with the police, the firefighters, and the general public.” Using the funds from the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving, Sánchez and her colleagues transformed the Spanish Action Coalition into La Casa de Puerto Rico, the community’s oldest social service agency.

In 1970, nearly half of the Puerto Ricans in Hartford were under eighteen years of age. Almost half, 44 percent, had migrated to Hartford to improve their economic status. Only 23 percent had a high school diploma or its equivalent and only 1.5 percent had a college degree. According to the Census Bureau, 27.6 percent of “Spanish-language” families, most of whom were surely Puerto Rican, and 45.1 percent of “Spanish-language” families below the poverty level received welfare in 1969. Median income for Hartford’s Puerto Ricans in 1970 was $4,556.

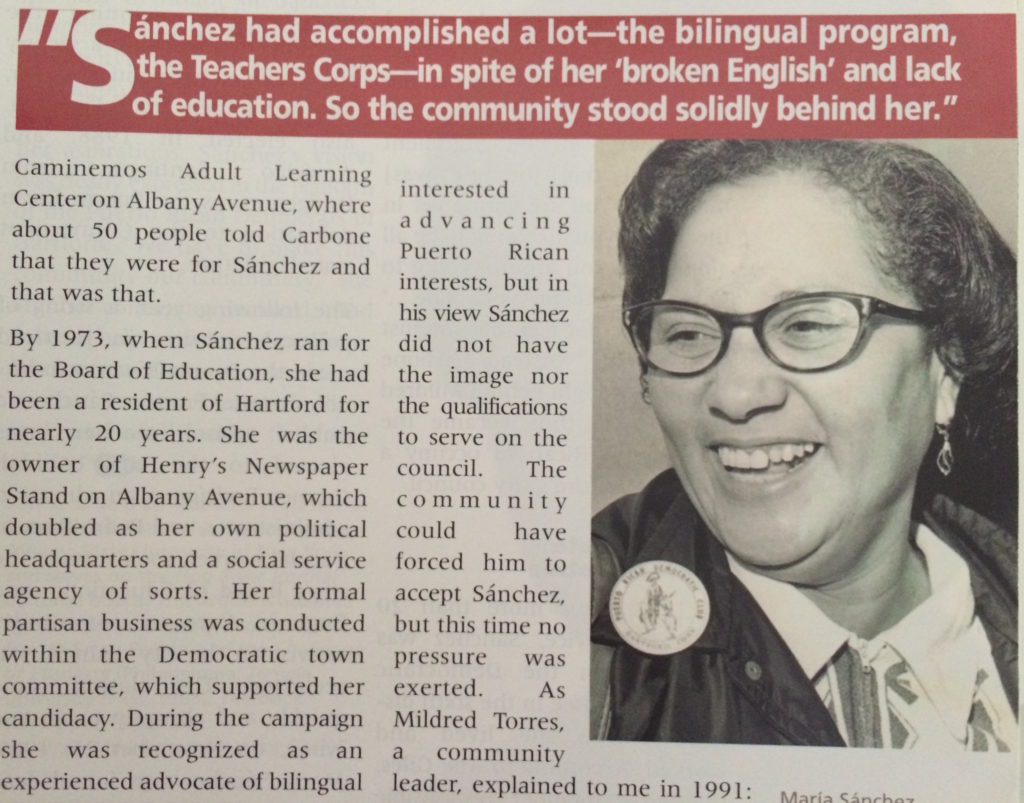

Except for age and welfare status, María Sánchez’s own situation—literate but uneducated, employed but poor—reflected the situation of the Puerto Rican community. This is how she portrayed herself during a community forum in 1979: “I know the problem,” she said about housing, “because I suffer it myself. I also live in a building where the rent is too high and it gets cold in the winter.” In addition, she had to contend with perceived drawbacks that, in all likelihood, were ascribed to her compatriots as well. During our conversation in 1991, Nicholas Carbone remembered her this way: “We ran María for the school board and she spoke broken English. She wasn’t an attractive woman, she was heavy, so where would you take her? How did you sell her? How did you get people to vote for her? And how [did]you get over the prejudice that she spoke with a thick accent? So we didn’t take her into a lot of neighborhoods…. You had to be practical as you were trying [to get her]on the school board.”

In 1971, Sánchez and University of Hartford professor Perry Alan Zirkel conceived a teacher-recruitment program, which, with funding from the federal government, began operations that year as the Teachers Corps. This program grew out of the longstanding efforts by Sánchez and others to hire Spanish-speaking teachers to address the educational needs of the increasing number of Puerto Rican children in the city’s school system. The Teachers Corps brought many Puerto Ricans to Hartford who later became prominent political figures in the city. By means of this program, Sánchez contributed to the development of a cadre of activists who, from the mid-1970s and through the 1990s, was the community’s best hope for political progress and socioeconomic advancement.

Also in 1971, along with community leaders Esther Jiménez, Antonio Soto, and Edna Negrón, Sánchez began to lobby the Board of Education to create a bilingual education program. Such programs were initially enabled by federal legislation passed in 1968. As a result of this effort “la escuelita” [the little school], a bilingual school, was established in 1972 on Ann Street, in the building formerly housing the St. Patrick/St. Anthony parochial school. But the campaign for bilingual education waged by Sánchez and her collaborators did not stop there. In 1978, as a result of a lawsuit filed in 1976, Puerto Ricans wrested from the authorities a consent decree mandating bilingual education throughout the public school system.

In 1973, when a position on the Board of Education became vacant, she pursued it. Carbone was opposed to this as well His preferred candidate was Edna Negrón, who bluntly told him to go to hell when he suggested that she was better than Sánchez. “My English was good, but María had the experience and the guts to do the job,” Negrón told me in 1993. “Besides, she had accomplished a lot—the bilingual program, the Teachers Corps—in spite of her ‘broken English’ and lack of education. So the community stood solidly behind her and we forced Nick to accept her.” That point was forcefully made in a meeting held at the Caminemos Adult Learning Center on Albany Avenue, where about fifty people told Carbone that they were for Sánchez and that was that.

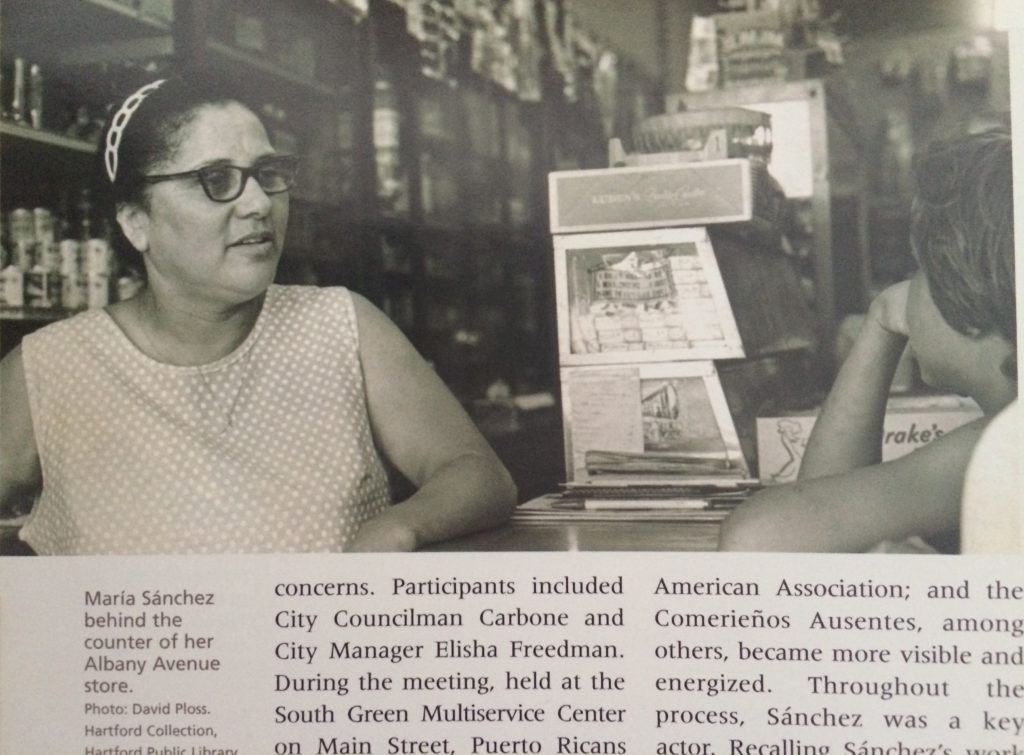

By 1973, when Sánchez ran for the Board of Education, she had been a resident of Hartford for nearly twenty years. She was the owner of Henry’s Newspaper Stand on Albany Avenue, which doubled as her own political headquarters and a social service agency of sorts. Her formal partisan business was conducted within the Democratic town committee, which supported her candidacy. During the campaign she was recognized as an experienced advocate of bilingual education. The Hartford Courant emphasized her endorsement by the Democratic Party, juxtaposing it to the greater political, administrative, and educational experience of other candidates. Sánchez was considered a symbol for a disenfranchised community and her candidacy was seen as a gauge of partisan influence. With the additional support of the Campaign Committee of the Bilingual Task Force, a group organized by La Casa de Puerto Rico, Sánchez became the first Puerto Rican elected to public office in Hartford.

In 1979, Sánchez once again expressed her interest in a council seat. While she was recognized for her political savvy, Nick Carbone again dampened her aspiration to work in the council. Carbone was truly interested in advancing Puerto Rican interests, but in his view Sánchez did not have the image nor the qualifications to serve on the council. The community could have forced him to accept Sánchez, but this time no pressure was exerted. As Mildred Torres, a community leader, explained to me in 1991: “The Hispanic political leadership had been after Nick, who was the controlling factor in the Democratic political machine, to have a Puerto Rican seat, and so when that opportunity arose, they went to him and said, ‘You have no excuses now, there’s a vacancy and we want it and you committed [your support for]it and you are gonna give it to us.’ ‘So who is the candidate to be,’ he asked… ‘Who do you want?’… María Sánchez identified herself as a candidate and people felt that she had the seat on the Board of Education and she should stay there.” Ignoring the will of the Democratic town committee, the endorsement of the mayor, several councilmen, and of the Hispanic Democratic Reform Club, Carbone refused to support Sánchez. During a conversation Antonio Soto and I had in 1991 he said: “María [had always]wanted to sit on the council and Nick Carbone would not let her. [Carbone’s argument was simply that] the time [was]not right. ‘You are gonna get in there, and you are going to be all alone, and you are not going to have anybody on your side….’ They made her feel that she just wasn’t ready.” Instead, Carbone threw his weight behind Mildred Torres, who thus became the first Puerto Rican to occupy a seat on Hartford’s city council.

In 1988, after more than twenty years of service, Sánchez was ousted from the Democratic town committee in the sixth district, where she lived and worked. According to Abe Giles, the party member responsible for this action, Sánchez was removed after failing to attend meetings and for not signing a consent slip to renew her membership. According to Giles, this “mistake” on her part could have been easily corrected except that “nobody seemed to want to.”

Sánchez saw the situation differently. She felt Giles, whom she had supported for well over a decade, had betrayed her. In her removal she saw a conspiracy to quash Puerto Ricans, who at this point were perceived by many African Americans as competitors for political power. On June 29, in a fit of ethnic indignation and personal anger, Sánchez announced she would run against Giles in a primary. The fight was for a seat on the state legislature. She won the primary by a narrow 33-vote margin. After winning the election in November, a victory that crowned her political career, Sánchez joined Juan Figueroa, also elected in 1988, and Américo Santiago, from Bridgeport, as the Puerto Rican delegation to the Connecticut state legislature.

The following year, a string of political victories in Hartford made the Puerto Rican community ecstatic: Frances Sánchez, a public school teacher, was elected to the city council; Carmen Rodríguez, an education administrator, and Pedro Ramos, a social worker, took seats at the city’s Board of Education; Eugenio Caro, a community activist on the city council, was reelected. The elation came quickly and abruptly to an end when, on November 25, 1989, María Sánchez was found dead in her apartment, probably of a heart attack. Unfortunately, the search for her replacement in 1990 led to divisions within the Puerto Rican political leadership precisely when unity was most necessary.

María Sánchez’s story belies the conventional wisdom about Puerto Ricans in the United States in more ways than one. She was a businesswoman, a dedicated activist, and a politician. While she was concerned about the status of Puerto Rico, her priority was to improve conditions for Puerto Ricans in her own community. She may have thought about returning to the island, but her overriding commitment was to Hartford.

Her involvement in Democratic politics was marked by loyalty to the party and a strong concern for issues affecting Puerto Ricans. At times she failed to cash in on her loyalty to advance Puerto Rican interests but this weakness was not the result of faintheartedness. In solidarity she was motherly but in conflict she could be unforgiving. Sánchez was the epitome of the ward-heeling politician, even if she conducted most of her business from behind the counter of her newsstand on Albany Avenue. For a long time she was the sole Puerto Rican in the city with sufficient recognition and standing to be politically credible and influential in and out of the Democratic Party. She was a driving force behind most of the community’s political achievements: winning concessions from the Catholic archdiocese in Hartford and the Democratic Party; helping organize influential groups; establishing crucial educational programs; and helping elect political figures, both Puerto Rican and otherwise. Relative to the cadre of middle-class professionals that emerged as leaders in the 1970s, she was politically conservative; when Edwin Vargas Jr. challenged the Democratic machine in 1977, Sánchez advised Nick Carbone to simply crush him. She was never close to the Puerto Rican Political Action Committee of Connecticut, a group that during the 1980s was one of the most electorally effective and influential in the city. However in other regards she was to the left of her party and in the vanguard of her community.

María Sánchez wanted first-class citizenship for Puerto Ricans as much as she wanted services and benefits for the Puerto Rican community. As she put it during a public forum at Immaculate Conception Church in 1979: “One of the reasons why I’m with the Democratic Party is to see what can be done for those of us who are here that are suffering the consequences of the decisions that are made without consulting the 30,000 Hispanics that live in this city.” Her concerns could be intensely parochial. For example, she was extremely unhappy when La Casa de Puerto Rico moved from Albany Avenue to Wadsworth Street. To her this meant that North End Puerto Ricans would not benefit from La Casa’s services as much as Puerto Ricans in Frog Hollow. But even this minor flaw must be seen in context–her interests were always selfless and focused on what she perceived to be the best for the greatest number. Nothing illustrates better her selfless regard than the fact that when she marched into the state legislature she did not know that the position carried a stipend, nor did she care.

In 1993, the María Sánchez elementary school opened its doors to the children of Frog Hollow. The school stands today not just in honor of Sánchez’s memory but as a testimony to a productive and fortunate life. Education was María’s passion. Politics was the vehicle that carried her aspirations. Sánchez’s vision was clearly expressed in the platform of the Puerto Rican Democrats of Hartford: “We have to make this community our community,” she and her colleagues declared, “and make it help us fight our problems. We have to show people around us that we can live with them and successfully adopt their way of life.”

In 1993, the María Sánchez elementary school opened its doors to the children of Frog Hollow. The school stands today not just in honor of Sánchez’s memory but as a testimony to a productive and fortunate life. Education was María’s passion. Politics was the vehicle that carried her aspirations. Sánchez’s vision was clearly expressed in the platform of the Puerto Rican Democrats of Hartford: “We have to make this community our community,” she and her colleagues declared, “and make it help us fight our problems. We have to show people around us that we can live with them and successfully adopt their way of life.”

José E. Cruz is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University at Albany, State University of New York. This article is adapted from his book, Identity and Power: Puerto Rican Politics and the Challenge of Ethnicity (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998). The book can be purchased at www.temple.edu/tempress for $24.95.

Subscribe to receive every issue of Connecticut Explored!