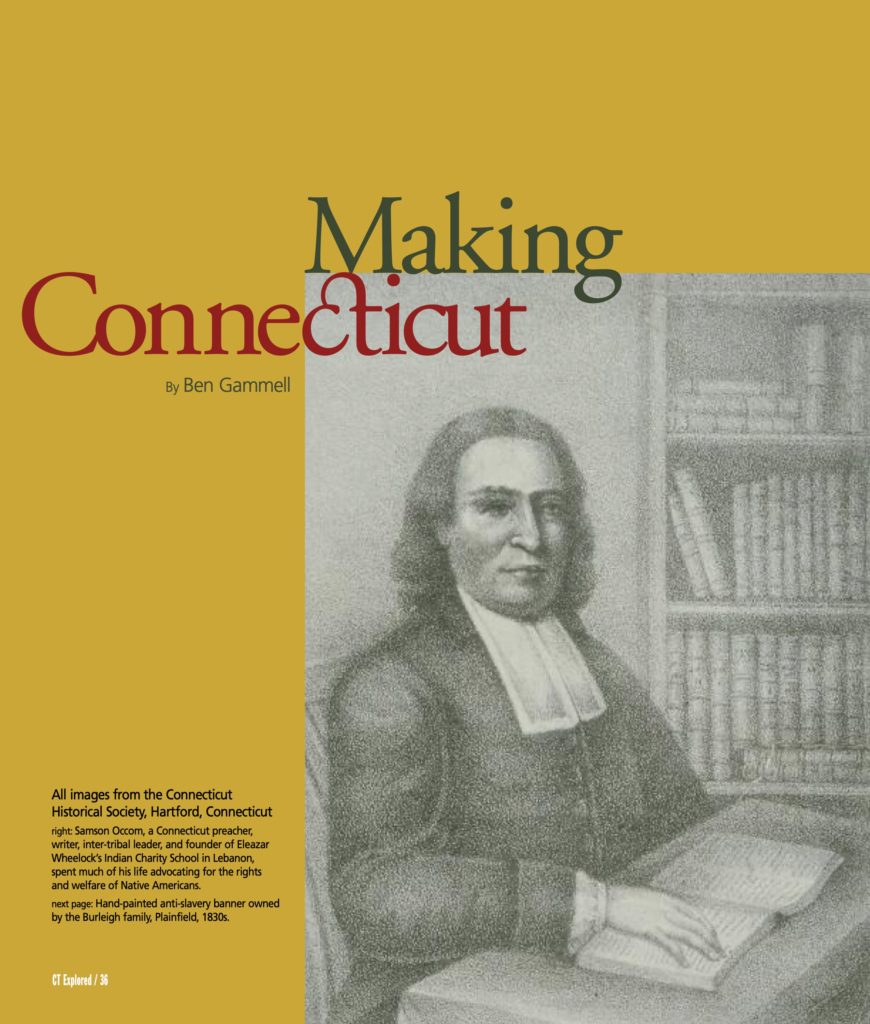

Samson Occom, a Mohegan, Connecticut preacher, writer, inter-tribal leader, and founder of Eleazar Wheelock’s Indian Charity School in Lebanon, spent much of his life advocating for the rights and welfare of Native Americans.

By Ben Gammell

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

INTRODUCTION: Making Connecticut, a permanent exhibition at the Connecticut Historical Society, offers an overview of Connecticut history through broad themes represented in artifacts, documents, and images that help connect us to this history today. Ben Gammell, coordinator of interpretive and education projects for the museum, selects a handful of objects and tells us why they were chosen for the exhibition.

Prominently displayed in the Connecticut Historical Society’s new permanent exhibition Making Connecticut is an 1853 edition of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 masterpiece Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Nearby is a copy of her older sister Catharine Beecher’s An Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism, with Reference to the Duty of American Females, published in 1837.

The message of Catharine Beecher’s essay is not what you might expect from the eldest sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe and early suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker. While Catharine–and the Beecher family–opposed slavery, she expressed a view commonly held in the 1830s that the abolition movement was inflammatory, dangerous, unchristian, and no place for women. Catharine, like many others, feared that the abolitionists’ insistence on immediate emancipation would push the nation toward civil war.

The insights offered by viewing those documents together are typical of the stories told by the more than 500 artifacts, documents, images, photographs, and items of clothing featured in Making Connecticut, which aims to show how Connecticut citizens’ lives, work, ideas, and experiences shaped the state’s—and often the nation’s—history from the 1500s to today.

“We are Usd very hard”

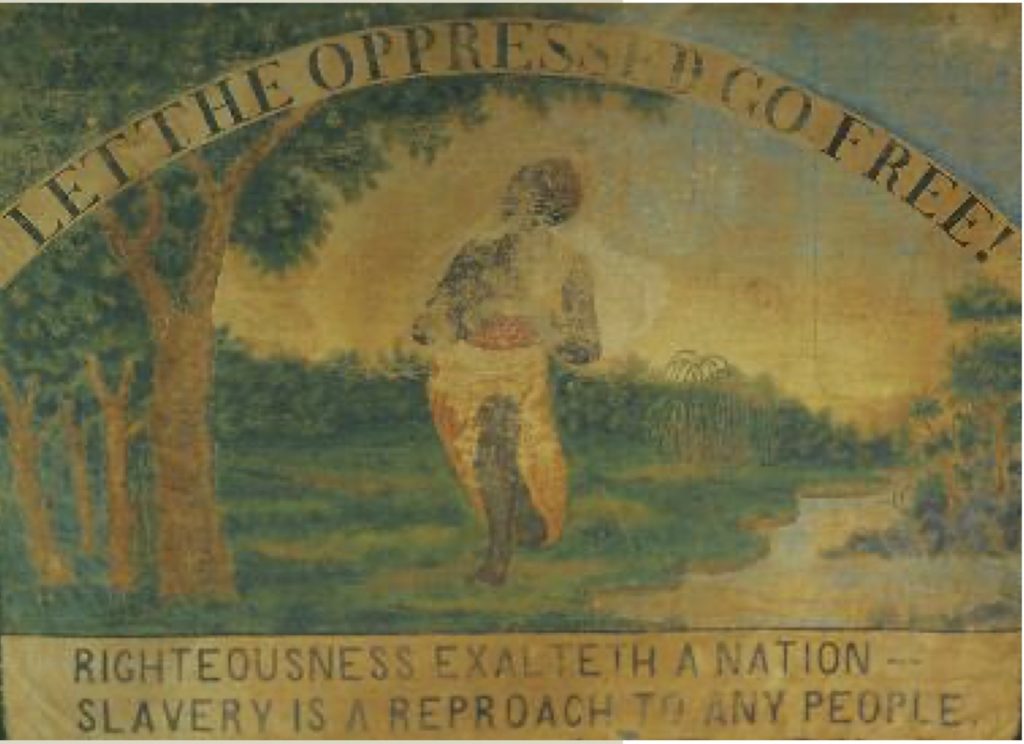

Hand-painted anti-slavery banner owned by the Burleigh family, Plainfield, 1830s. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

Around 1787, in the newfound glow of American independence, Samson Occom, a Mohegan from Connecticut, wrote a congratulatory letter to the governor of New York:

“We desire to be permitted, to rejoice with you in your great deliverance from the Cruel Tyranny of your once King . . . [You] have got your great Freedom, Liberty, and Independence, by your firm Resolution, Great Boldness, and undaunted Courage. You have now Shook off the Cruel Shackels and the hard and rough Yoke of Bondage, and now you are a free People, you have your own Power in your own Hands.”

Samson Occom was a Connecticut preacher, writer, inter-tribal leader, and founder of Eleazar Wheelock’s Indian Charity School in Lebanon. His letter to the governor was not in fact one of congratulation but a petition for justice. Occom spent much of his life advocating for the rights and welfare of Native American communities, writing letters and petitions to people in power in Connecticut, New York, and the U.S. Congress. In this petition on behalf of the Shinnecock tribe of New York, Occom got to the point:

“We have a little bit of Land that we Call our own, but the English have got all the profet of it, they Claim al the grass and feed, and we Cant keep any Creatures; we can only Plant a little Corn, beans and Pumpkins, and thats all, And we think, we are Usd very hard, woud they be willing to be Usd in this manner? We think it is Writen in the Good old Book, Blessed is he that Considereth the poor . . . And we know it is in your Power to help us.”

Occom’s petition appears in Making Connecticut alongside objects and images rich with American symbolism such as eagles, classical Greek architecture, and George Washington’s likeness. The spirit and optimism of these symbols—found on everyday items such as a pewter bowl made in Rocky Hill, a chair from Hartford, and a porcelain tea bowl—contrast with items representing those who were excluded from America’s new opportunities and prosperity. A poster announces a $10 reward for the return of 18-year old Caesar, an escaped slave from Woodstock. And next to Occom’s petition is the 1798 autobiography of Venture Smith, an African who was kidnapped and sold into slavery in New York and Connecticut. Smith, who purchased his own freedom and that of his wife, two sons, a daughter, and three more enslaved men, wrote, “My freedom is a privilege which nothing else can equal.” Displayed next to his book is a humble wooden flour scoop that belonged to his son, Cuff.

“Power rests in the people. Not a part of the people”

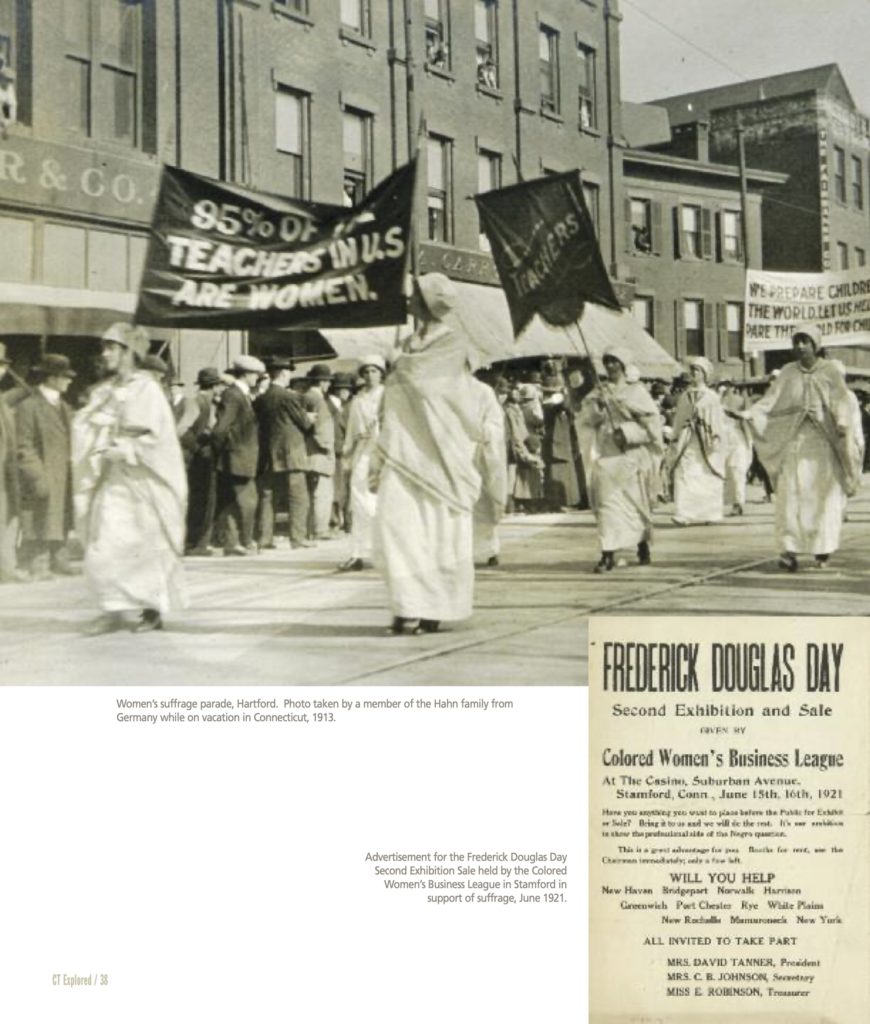

top: Women’s suffrage parade, Hartford, 1913. bottom: Advertisement for the Frederick Douglas Day Second Exhibition Sale held by the Colored Women’s Business League in Stamford in support of suffrage, June 1921. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

A small booklet with an image in purple ink of the Statue of Justice is the official program for the “Votes for Women Pageant and Parade,” held in Hartford on Saturday, May 2, 1914. The parade was mounted by the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association, founded in 1869 by Isabella Beecher Hooker as the first official organization in Connecticut to fight for women’s right to vote. The booklet states the CWSA’s case: “We call our country a democracy, and pride ourselves upon its being one. What is a democracy? A democracy is a form of government where the final power rests in the people. Not a part of the people; that makes an oligarchy or a monarchy; but where it rests in the whole people.” The program lists 61 suffragist groups in Connecticut, including the Connecticut Men’s League for Woman Suffrage, and claims18,000 active and enrolled members of the CWSA.

The Hartford Courant reported that more than 1,000 participants marched in the parade, and thousands more came out to watch. Ethel Murray of Guilford led the procession on horseback, dressed as Joan of Arc, and participants carried banners or rode on floats. Many of the floats reflected themes celebrating the progress of women, such as “Entrance into Public Schools,” “Entrance into Colleges,” and “Entrance into the Professions.” The Courant remarked on a woman marching alone, “carrying in her arms a tiny baby . . . to show Hartford that even mothers wanted very much to vote.”

The parade attracted plenty of “anti-suffragists” too; they wore red paper flowers to the event. The Connecticut Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, organized in 1910, advocated for women’s non-political role in society and distributed flyers, including one displayed next to the parade program. “Some Reasons Why We Oppose Votes for Women” begins with “the oldest and shortest of reasons: Because man is man, and woman is woman. Nature has made their functions different, and no constitutional amendment can make them the same.”

One woman wrote to the Courant in a letter signed “E.B.G.,” saying the parade was a waste of time and money. “If the majority of the women who take part in this parade would be honest with themselves they would confess that they were marching . . . to satisfy an unwholesome craving for the limelight—one of the deplorable tendencies which marks this movement as a whole. Think what it would mean if these women would devote the time and effort demanded by the parade to philanthropic, civic or church work—countless good causes are begging for workers, are bemoaning the fact that their usefulness is crippled for want of the very time and strength so recklessly squandered on May 2.”

Women of color also gained a voice with the passage of the 19th Amendment. [See “Uncovering African American Women’s Fight for Suffrage,” Summer 2020.] On display is a 1921 advertisement for a “Frederick Douglas Day Second Exhibition and Sale” given by the Colored Women’s Business League in Stamford, an event where the “Colored Womens’ National Voters League” planned to “call the STATE OF COLORED WOMEN VOTERS together, for the purpose of organizing a State Voters League.”

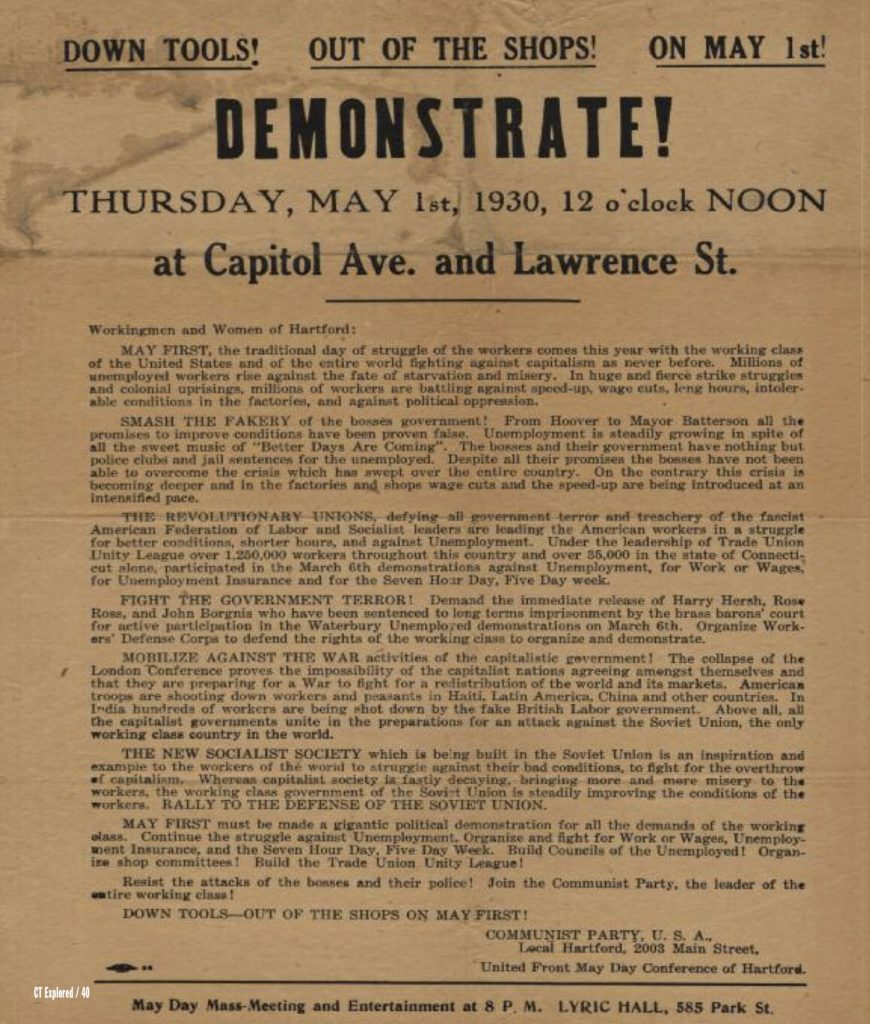

“Down Tools! Out of the Shops!…Demonstrate!”

Communist Party broadside promoting a May 1 demonstration, Hartford, 1930. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

A small leaflet from 1919, “THREE WAYS TO FIGHT YOUR BATTLE,” highlights the story of organized labor in Connecticut. It advocates for workers to fight for their rights by joining a union, joining the Labor Party, and subscribing to The Labor Standard. Organized labor grew in numbers and influence in the late 1800s and early 1900s as industrialization continued to expand and immigrants from Europe—Irish, Italians, Hungarians, Poles, and Russians—increased the country’s low-skilled labor force. Factories provided jobs and opportunities, but also employed children and demanded long hours with dangerous working conditions.

According to a 1902 report of the Connecticut Bureau of Labor Statistics, the aims of Connecticut unions included “out of work benefits, sick benefits, strike benefits, to secure shorter hours of labor, to secure better wages, to secure better conditions generally, to prevent unjust or unfair treatment of members . . . wife’s funeral benefits, death benefits, disability benefits . . .” and more. The Connecticut Federation of Labor, the state’s largest union, was organized in 1887. Between 1899 and 1903, the number of unions in Connecticut nearly tripled, from 214 to 591. Union workers lobbied for changes in legislation, supported or submitted political candidates, and organized strikes—which often turned violent—to achieve new rights.

“Down Tools! Out of the Shops! On May 1st! Demonstrate!” reads a 1930 handbill distributed by the “Communist Party, U.S.A., Local Hartford” calling for a gathering at Capitol Avenue and Lawrence Street. This document brings into play (if you read the smaller print, that is) the more radical agendas some unions supported. It is also a reminder of the widespread apprehension that characterized the outset of the Great Depression: “Unemployment is steadily growing in spite of all the sweet music of ‘Better Days are Coming’. The bosses and their government have nothing but police clubs and jail sentences for the unemployed. Despite all their promises the bosses have not been able to overcome the crisis which has swept over the entire country. On the contrary this crisis is becoming deeper and in the factories and shops wage cuts and the speed-up are being introduced at an intensified pace.” The handbill exhorted workers to “fight the government terror” and “rally to the defense of the Soviet Union.” As a Hartford Courant article reported the day after the demonstration, turnout was poor, and several of the scheduled speakers failed to appear.

Making Connecticut seeks, among other goals, to show how people’s lives, work, and ideas have changed from the 1500s to today and how people have initiated or responded to those changes. Catharine Beecher criticized abolitionists for their tendency to “generate party spirit, denunciations, recrimination, and angry passions,” language that resonates in today’s climate of political polarization and uneasy civil discourse. Making Connecticut, the only permanent exhibition to offer a full overview of Connecticut history, traces broad themes across 500 years. But its artifacts, documents, and images help connect us to real people who struggled with changing ideas in ways that are familiar toda

Ben Gammell is coordinator of interpretive and education projects at the Connecticut Historical Society.

Explore!

The Connecticut Historical Society

1 Elizabeth Street, Hartford

Making Connecticut is on view during regular hours.

For a virtual tour, visit https://chs.org/online-exhibition/virtual-tour-making-connecticut/

Read more about Women’s Suffrage, Labor History, and Native Americans in Connecticut and more on our TOPICS pages. Find a Grating the Nutmeg podcast about Samsom Occum.