by William Hosley WINTER 2005/06

by William Hosley WINTER 2005/06

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

My passion for Coltsville, the 19th-century Hartford home and factory complex of entrepreneurial gun-makers Samuel and Elizabeth Colt, was kindled almost 20 years ago. As curator of Americana and American decorative arts at the Wadsworth Atheneum, I was contacted by The Hartford Courant and the state attorney general’s office, both of whose interest in the status of the Atheneum’s Colt firearms collection had been piqued by a controversial gun trade by former staff at the Museum of Connecticut History.

A quick inventory revealed that the Atheneum’s Colt collection was intact. But this time it was my interest that was piqued. I was astounded to learn how much more there was to the collection than guns. The firearms were the tip of an iceberg that inspired me to probe deeper; my research culminated in the Atheneum’s 1996 Sam & Elizabeth: Legend and Legacy of Colt’s Empire exhibition and accompanying catalogue.

Getting the green light for Colt’s Empire wasn’t easy. It was the height of the anti-gun hysteria in the media, and the Colts’ taste in art was so out of sync with Modernist sensibilities that other curators regarded it as unworthy of museum display. A whirlwind tour of Coltsville with then-Atheneum director Patrick McCaughey convinced him the show was worth doing.

Admittedly, I stacked the deck. I had asked friends at Armsmear-the Colt mansion that is now a retirement home for widows of Episcopal clergy and other “women of good character”– to let us up into the tower, one of the most alluring historic spaces in Connecticut. Peering out across the horizon, having just viewed Colt’s Armory, the worker housing, Colt Park and statue, and the family carriage barn, McCaughey had a ” Eureka !” moment. Astonished at how much of this lost world of Coltsville was still intact; McCaughey agreed that however one felt about guns and gaudy Victorian art, there was something profound about the integrity of what Hartford and the Atheneum had to show and tell.

Coltsville’s History Unrivaled

Coltsville was not the first or the most famous factory town. But as a model it was unrivaled in its day and is one of the most intact and best-documented examples in America . America ‘s most famous factory town was Pullman , Illinois . Coltsville was never as large, as prominent or as tightly controlled. But, even though it was conceived and developed thirty years earlier, it shared an astonishing range of amenities with Pullman: worker housing, a reading room and library, a school, a park with miniature lake, a theater, a church, manicured lawns and a military band, all aimed at creating the kind of morally salubrious environment Colt believed was most conducive to good work and good living.

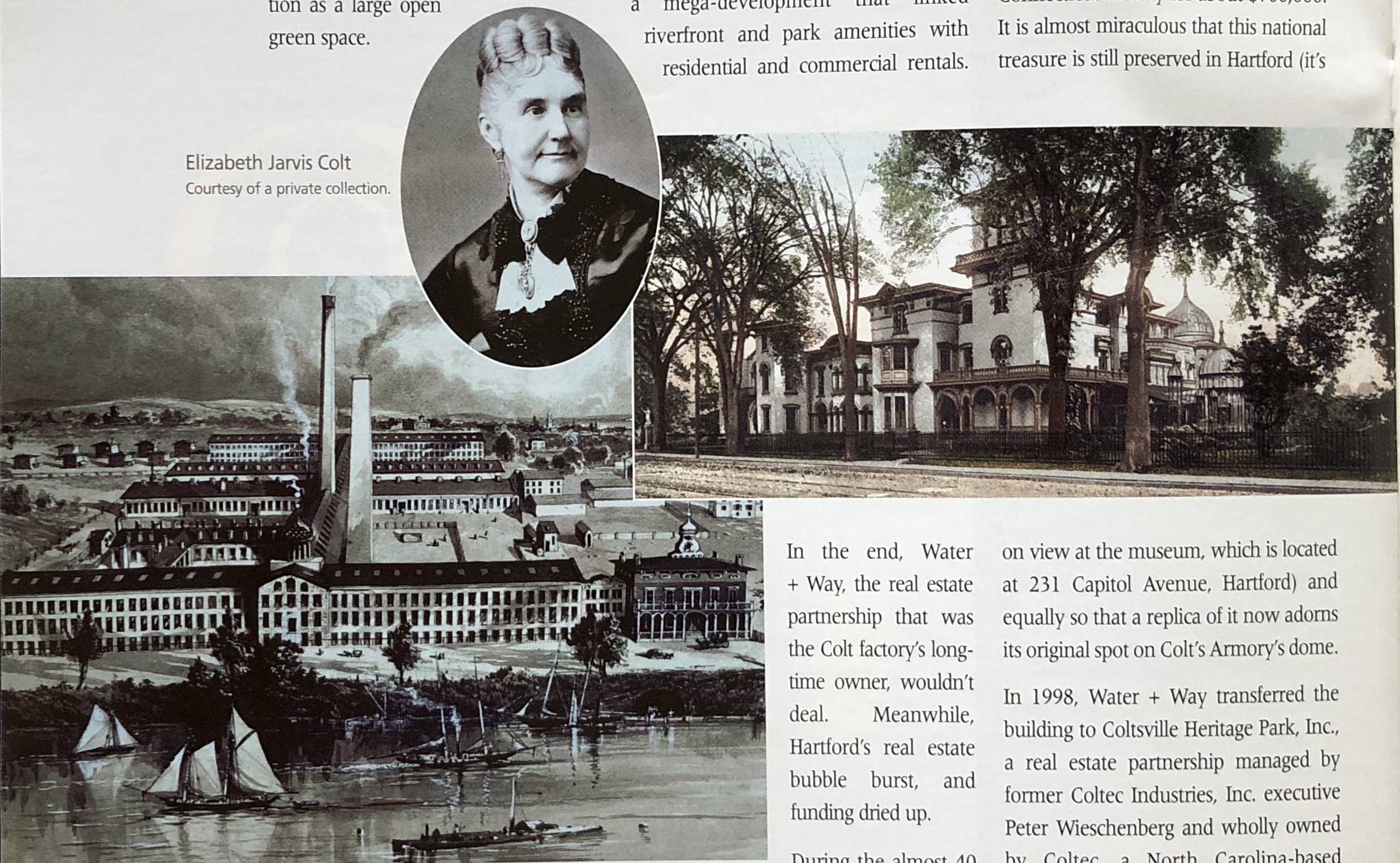

bottom left: The Colt Armory before it mysteriously burned down during the Civil War. private collection; top right: Armsmear (Samuel Colt House), 50 – 90 Wethersfield Avenue, Hartford, 1857, attributed to architect Octavius Jordan. private collection

Surprisingly, there is little record of what Coltsville’s residents and the people of Hartford thought of Colt’s model town-which he, perhaps recognizing the monarchical overtones of the model, named, prosaically, the “South Meadow Improvements.” The name Coltsville was adopted informally and possibly with some degree of sarcasm by neighbors and residents who understood that it was, in all but name, an urban industrial plantation, complete with a big house and ruling master.

Sam Colt conceived the idea for Coltsville in 1851 while representing American manufacturing at the famous Crystal Palace Exhibition in London , where he witnessed firsthand British model industrial communities. In one of the boldest real estate development campaigns in Hartford ‘s history, Colt acquired 250 acres of land and built two miles of dyke to protect against flooding. There, by 1856, Colt built and occupied: the largest Armory in the world (500 feet long and 4 stories tall), worker’s housing, wharf and ferry facilities on the Connecticut River , and a gathering place named Charter Oak Hall for the instruction and amusement of his employees. Crowning the hilltop in the northwest corner of the complex was Armsmear, the enormous Italian Villa dream house Colt built for himself and his new bride Elizabeth Hart Jarvis in 1857.

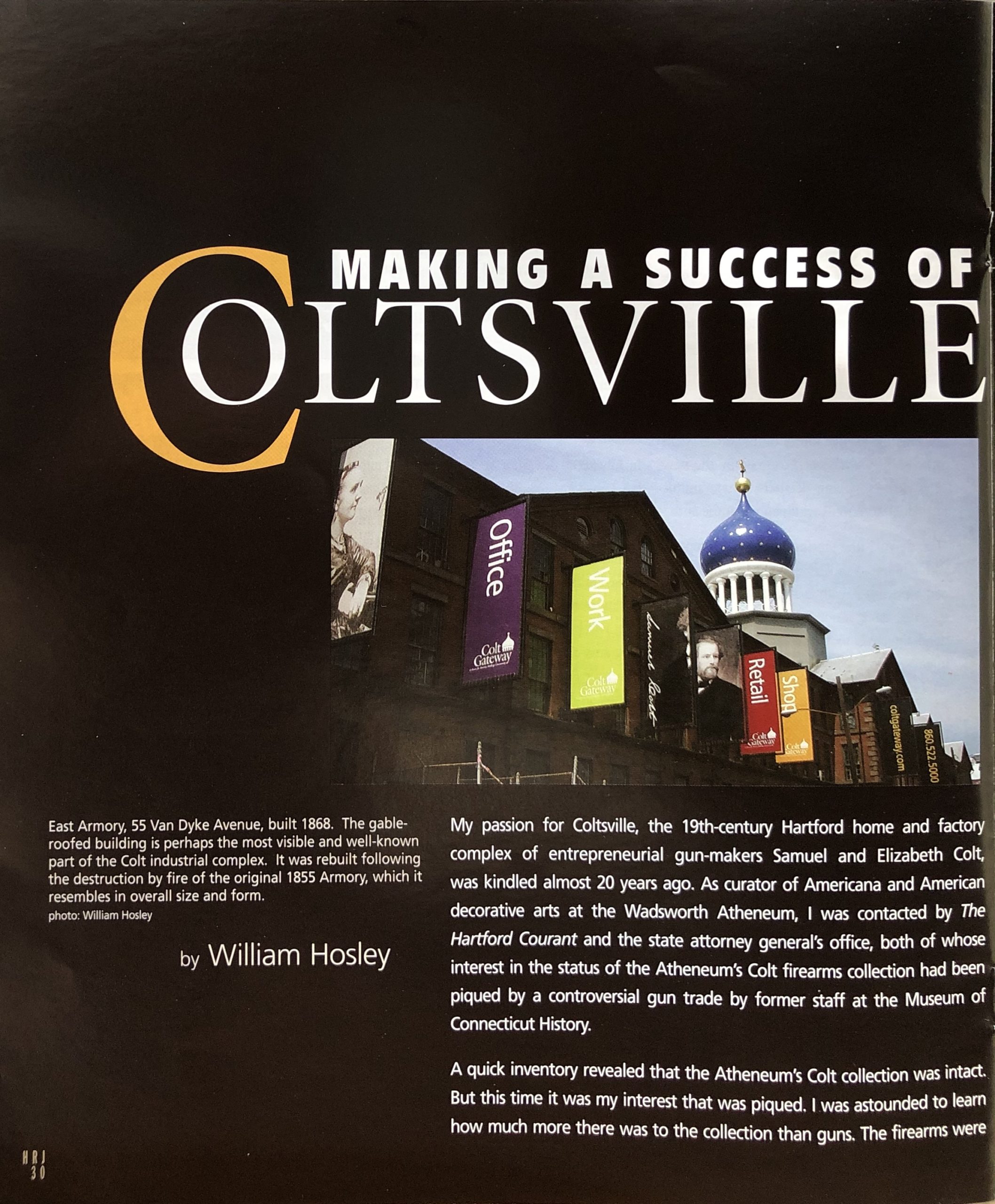

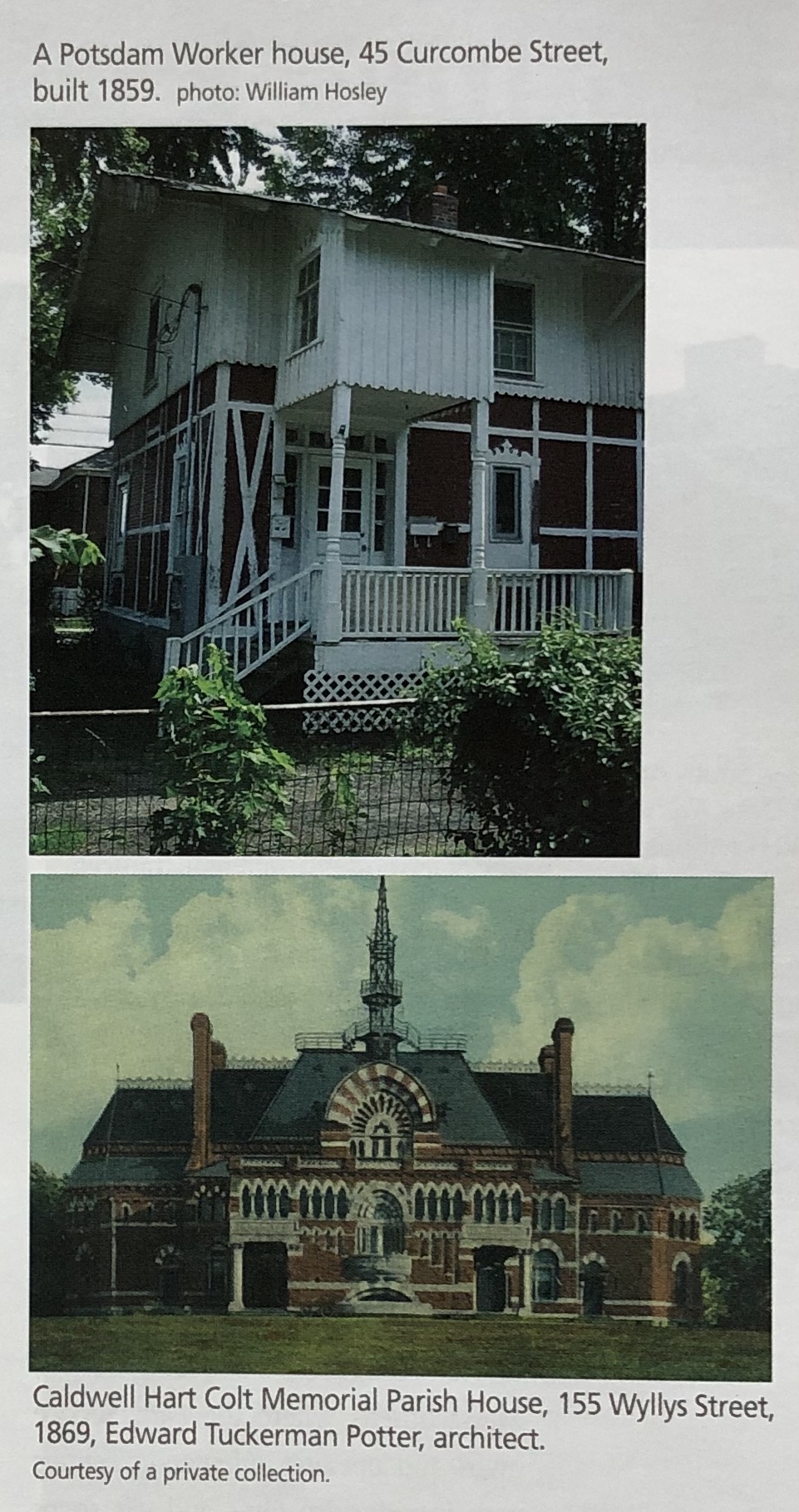

At the time of Colt’s death in 1862, the factory town had expanded to include additional worker’s housing, stables and greenhouses, a cartridge works, and Colt’s Willow Works (which manufactured wicker furniture) along Curcombe Street . The Armory produced one thousand arms a day. It was burned-reputedly by Southern arsonists-during the Civil War. The factory was rebuilt in 1868 by Colt’s widow and remains to this day the most tangible evidence of this once great industrial empire. The willow workers lived in “Colt’s Swiss cottages,” a row of stylish brick tenements (many still standing) built at the south end of Coltsville.

The Church of the Good Shepherd (1868) and Caldwell Colt Memorial Parish Hall (1894), at the north end of Coltsville, were built as memorials by Elizabeth Colt. Elizabeth founded a Sunday school for the armory workmen in 1859, and, after Sam’s death in 1862, she began planning for a grand memorial church. When it opened in 1869, it was described as the finest church in America . Its ornamentation, layout, and stained glass reflect the most advanced capabilities of the age. Following Elizabeth ‘s death in 1905, her will gave the gardens and grounds at Armsmear to the City of Hartford to be developed as Colt Park .

While Colt Park has changed dramatically, it still adds to the district by including the Colt Memorial Statue, numerous Colt-period trees and landscape features, and two important Armsmear-related ancillary structures. The park also continues its historic function as a large open green space.

Recapturing Coltsville

One of the first people I met when I began my work with Colt was Thomas Standish, a prominent Hartford real estate developer in the 1980s. Standish is a visionary who admired the Colt complex and regarded it as the crown jewel of his increasingly successful effort to transform the Sheldon-Charter Oak neighborhood into a competitive mixed-used commercial and residential development zone. Having built the Hartford Square North office complex and rehabbed the old Atlantic Screw Works factory, Standish began exploring long-term lease arrangements for underutilized acreage in Colt Park near the Colt’s Armory complex, aiming to create a mega-development that linked riverfront and park amenities with residential and commercial rentals. In the end, Water + Way, the real estate partnership that was the Colt factory’s longtime owner, wouldn’t deal. Meanwhile, Hartford ‘s real estate bubble burst and funding dried up.

During the almost 40 years that Water + Way managed the site (the Colt’s Manufacturing Company sold the building in the 1950s but remained its primary tenant until 1993), property manager Roy Orbell transformed the Colt complex into artists lofts and studios, well ahead of that trend.

During the almost 40 years that Water + Way managed the site (the Colt’s Manufacturing Company sold the building in the 1950s but remained its primary tenant until 1993), property manager Roy Orbell transformed the Colt complex into artists lofts and studios, well ahead of that trend.

The withdrawal of Colt’s Manufacturing as a tenant apparently changed everything. By 1995 Water + Way was ready to sell. But not before stripping the building of the famous Rampant Colt statue atop the onion dome. The consortium of Connecticut-based art and arms dealers who bought the horse peddled it all over Europe and Japan . Their timing was off, though, and the horse eventually was rescued by the Museum of Connecticut History for about $700,000. It is almost miraculous that this national treasure is still preserved in Hartford (it’s on view at the museum, which is located at 231 Capitol Avenue, Hartford ) and equally so that a replica of it now adorns its original spot on Colt’s Armory’s dome.

In 1998, Water + Way transferred the building to Coltsville Heritage Park, Inc., a real estate partnership managed by former Coltec Industries, Inc. executive Peter Wieschenberg and wholly owned by Coltec, a North Carolina-based industrial conglomerate that originally grew out of the Colt’s Manufacturing Company. Although Coltec had some experience developing former industrial sites associated with their companies, the magnitude and complexity of this project was apparently overwhelming. Still, Wieschenberg oversaw an impressive restoration of the Colt Dome and successfully appealed to the state for support in environmental cleanup. But progress was slow.

By the 1990s, it clearly was time for new vision. The state opted to invest heavily in the riverfront Adriaen’s Landing development to the north of Coltsville. Former Governor John Rowland and former Phoenix CEO Robert Fiondella deserve credit for recognizing that it was time for a major initiative to revitalize Connecticut ‘s declining flagship capital city. In 1998, Adriaen’s Landing was launched as one of the Governor’s “Six Pillars of Progress,” that included, among other things, the adaptive reuse of the former G. Fox department store, the Morgan Street Garage, and the Connecticut Convention Center . While Coltsville was not included in the project mix, its location and prominence guaranteed that it was never out of sight or out of mind.

By 2000, with hundreds of millions of state dollars invested in a nearby convention center and related amenities, Coltsville finally attracted the attention of developers with substantial experience managing complicated projects, not to mention expertise in the arcane accounting and legal provisions of financing such an effort. New York-based Homes for America Holdings, Inc., with a billion dollars in prior development experience behind them, took possession of the complex and began making improvements that have given Coltsville a whole new spirit.

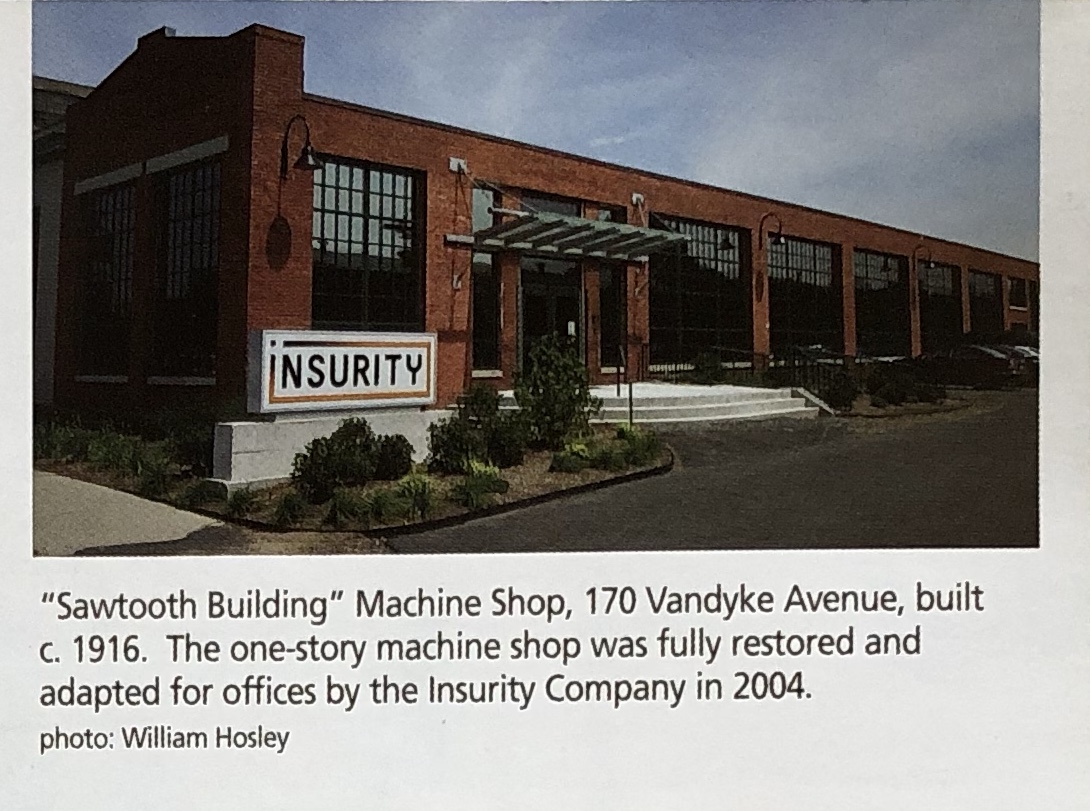

Dubbing their new project the “Colt Gateway” development, Homes for America created a master plan that divided the complex into manageable parts, beginning with replacing the mechanicals and environmental controls and restoring the old steam plant on Vredendale Avenue . The adjacent building was also restored and leased for use as a school and offices. In 2003 the massive “Sawtooth building” underwent a state-of-the-art adaptive reuse and is now the home base for Insurity, a company that supplies tech services to the insurance industry.

Business and political leaders began to catch the spirit. Since 1999 The Hartford Courant has been Coltsville’s staunchest advocate, dubbing it the “seventh pillar of progress.” The arrival of publisher Jack Davis at The Courant in 2000 brought even a more preservation-minded perspective to Connecticut ‘s largest newspaper. In 2002, The Courant organized a Key Issues Forum involving U.S. Senators Dodd and Lieberman and U.S. Representative Larson in a lively discussion about Colt heritage.

Congressman Larson subsequently initiated legislation to fund a National Park Service study to determine the feasibility of creating a Colt-themed National Historic Site. Larson’s Hartford office Chief of Staff Elliot Ginsberg convened an ad hoc committee on the Coltsville National Park Project, of which I am a member. Over the past two years we’ve worked closely with staff from the Boston office of the National Park Service to seek National Historic Landmark designation from the Department of the Interior, an important precedent to securing National Historic Site status and funding.

The resulting 60+-page nomination not only provides a painstakingly documented portrait of the evolution and development of the Colt factory complex and its related amenities but provides a remarkably coherent argument for Hartford ‘s significance in American industrial and economic history.

Congressman John Larson observed that, “Before Henry Ford and Detroit , there was Samuel Colt and Hartford . Colt was a visionary, and his advancements in mass production revolutionized American industry. Indeed, Colt is a transformative figure in our history. He is inextricably tied to the pivotal events and figures that shaped America and grip our collective imagination: the Gold Rush; the Texas Rangers and the Mexican war; the Civil War; Jesse James, Wyatt Earp and the Wild West. Any study of history- America ‘s or Hartford ‘s-is incomplete without a discussion of his influence. In designating Coltsville a national park, the federal government has an opportunity to expand upon our country’s narrative by highlighting the contributions of one of its most instrumental, transcendent figures.”

Transforming Coltsville into a National Park

Ideally, a Coltsville National Park would bring together half a dozen stakeholders, each contributing their piece of the story, with the whole tied together and promoted by the National Park Service. Such an approach is similar to that used in New Bedford , Salem , and Boston , Massachusetts where the Park Service owns and operates orientation centers with introductory films and gift shops while relying on existing independent attractions to “deliver the experience.” Components of that experience could include exhibits and self-guided tours linking existing sites that include the riverfront, gardens, monuments and sculptures, art, museum collections, architecturally significant buildings, and more. Elements missing or altered can be suggested by installing outdoor interpretive signage.

Who are these “stakeholders” and what are the possibilities? Chief among them is the Elizabeth Hart Colt Collection and Colt Memorial Wing at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. When Elizabeth Colt died, a hundred years ago, she bequeathed to the Wadsworth Atheneum the Colt Memorial Collection and funds earmarked for the sole purpose of erecting a building to house it. Although the Colt building remains, the museum hasn’t displayed Colt collections there permanently since 1982, though an upcoming exhibition opening in May 2006 will provide display space for guns and related material for the first time since then.

The Atheneum’s collection includes patent prototypes, production models both from Colt’s Paterson , New Jersey and Hartford factories, and Sam Colt’s important collection of historic repeating firearms. But the collection is especially rich in art and decorative arts that speak to the Gilded Age sensibility and tastes of Elizabeth Colt. The Museum of Connecticut History also owns a major collection of firearms and Colt company memorabilia that was donated by the company in the 1950s. The museum has also assembled Connecticut ‘s best collection of machine tools, manufactured products, and marketing memorabilia related to the revolution in precision manufacturing spawned at Colt’s. The two collections are surprisingly complementary and extensive enough that one can easily imagine a collaborative partnership culminating in three outstanding, destination-quality experiences involving a major permanent display focusing on Elizabeth Colt at the Atheneum, another permanent display dealing with aspects of Colt and Connecticut industrial heritage at the Museum of Connecticut History, and an orientation exhibition at a Coltsville-based visitor center.

Other key resources include

- The Colt Trust’s Armsmear, Church of the Good Shepherd, and Caldwell Colt Memorial House. Elizabeth Colt’s will was explicit and unambiguous in signaling her intent to preserve these buildings as memorials, places where memories and memorabilia are preserved and presented as living reminders. Although Elizabeth Colt could not have anticipated the booming economy and demand for “culture” in 20 th -century America , she prepared for it exquisitely by preserving most of what one would need to capture the taste and sensibility and tell the story of this period in American history. There are numerous models for how churches and facilities like Armsmear can function effectively while serving as both places of worship and repose and aslearning environments that invite public attention.

- More than 40 individual historic structures dating from the 1854 Colt’s Armory forging shops, to the 1942 Colt’s Manufacturing office building and a substantial quantity of manufacturing space built during the boom years around World War I

- A new visitor center and parking at or near Colt Gateway’s Colt’s Armory building.

- The City of Hartford ‘s collaboration with the Hartford Botanical Garden in a planned restoration and redesign of the Colt Carriage House, Gardener’s Cottage, and gardens near the Colt Memorial Statue.

Satellite resources of considerable interest include

- The greater Wethersfield Avenue historic district with its Colt-related stories.

- Charter Oak Place historic district with its Colt-related resources.

- Capewell Manufacturing.

- The Polish National Home.

- The custom shop and archives at Colt Manufacturing Company in West Hartford .

- The Colt Monument and related monuments at Cedar Hill Cemetery .

- The Colt family plot at Old North Cemetery .

What’s in it For Us?

Why bother with Coltsville when the city and its cultural attractions already face so many challenges?

Hartford Mayor Eddie Perez explains that “Coltsville matters because it is a vital part of the City’s renaissance. It speaks to the heart of what this City is all about. We’re using this 19 th -century gem as a magnet for 21 st -century innovation. [It can] help people rediscover the magic that exists here.”

The stakes are high and the competition is fierce. If Hartford does not play its Colt card, it will be hard-pressed to compete in the global economy. The combined forces of globalization and homogenization are forcing cities, states, regions, and locales to participate in a global tourism beauty contest that will increasingly divide haves from have-nots, destinations from pass-throughs and places that generate buzz from places that get little respect, even from those who live there. It’s unfolding fast and furiously, with the plum images and reputations being scooped up by places that understand the new rules of engagement.

The stakes are high and the competition is fierce. If Hartford does not play its Colt card, it will be hard-pressed to compete in the global economy. The combined forces of globalization and homogenization are forcing cities, states, regions, and locales to participate in a global tourism beauty contest that will increasingly divide haves from have-nots, destinations from pass-throughs and places that generate buzz from places that get little respect, even from those who live there. It’s unfolding fast and furiously, with the plum images and reputations being scooped up by places that understand the new rules of engagement.

If Congressman Larson, and Senators Dodd and Lieberman are successful in securing Federal support for a Coltsville National Historic Site, and if the state steps in to match it, the challenge will be ours to either run with the ball or drop it. Getting it done and done right will not be easy and will require a quality of teamwork, leadership, faith, and inter-institutional collaboration that has not always been abundant. But considering the rewards-a likely doubling or tripling of visitation and a national reputation as a heritage and arts destination-it seems like a no-brainer to me.

William Hosley serves on the ad hoc committee working to create a Coltsville National Historic site. He was formerly the curator of American decorative arts at the Wadsworth Atheneum.

Explore!

“The Suspicious Colt Armory Fire,” Fall 2006

“Sam Colt Mines the Arizona Territory,” Winter 2016-2017

“How Connecticut-Made Guns Won the West,” Winter 2016-2017