by Chris Dobbs with Nancy O. Albert

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

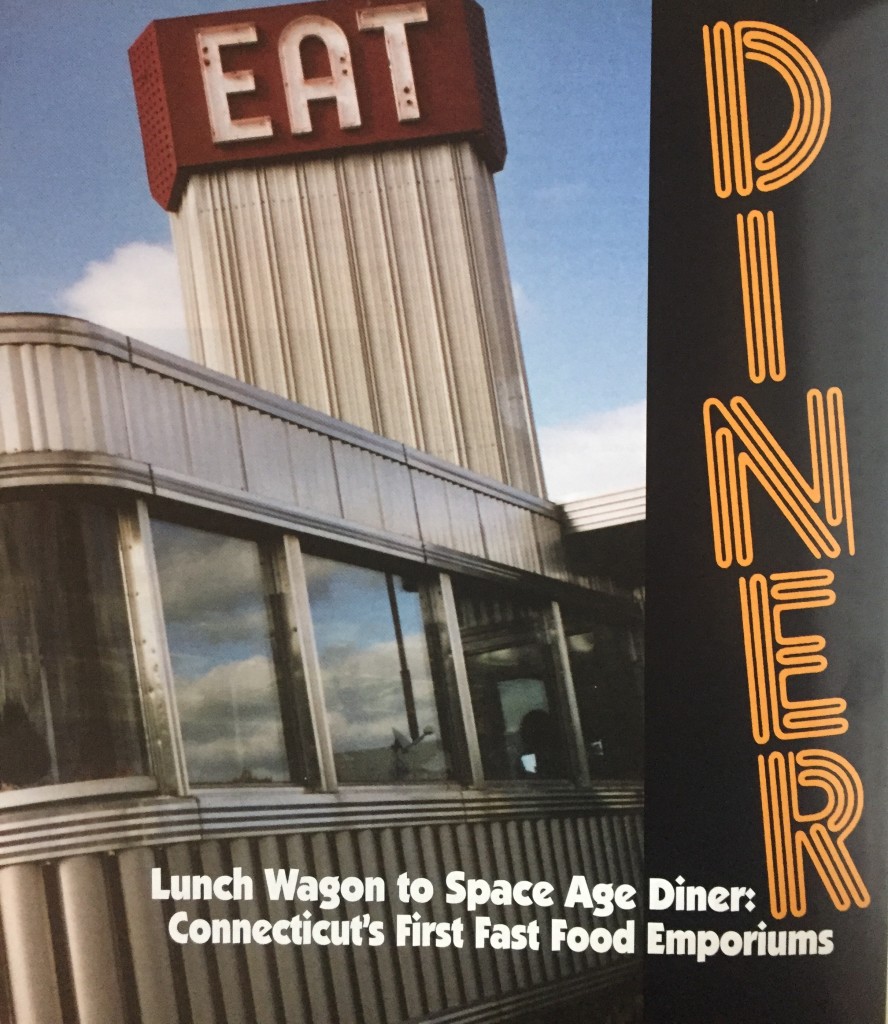

Few institutions reflect Americans’ twin love affairs with transportation and food better than the American diner. Since their first appearance in the late 19th century, diners have dotted the Northeast’s roadways; they’ve taken their place in America’s culinary history and today are embraced as pop-culture icons. Shiny, curved, colorful, and often noisy and crowded, diners have long been beacons to the motorist, the mill worker, the truck driver, the family caravan, and pilgrims in search of the perfect BLT, burger, or breakfast. With approximately 100 of these stand-alone, independent eateries, Connecticut is home to some of the nation’s most archetypal and eclectic diner architecture.

The diner is a uniquely American creation that over the past 30 years has sparked much roadside attention. In an attempt to define it, historians have typically applied four essential standards: the structure must be prefabricated and hauled to a site; the dining area must feature a counter and stools; the menu must consist of “home cooking” at reasonable prices; and the cooking should take place behind the counter(1).

A fifth characteristic is often overlooked: The American diner’s architecture has always been linked to transportation. Connecticut’s diners, like those throughout the country, began as simply wagons, reflecting a major mode of transport. As public transit evolved, so did diners: their design mimicked that of the Pullman railroad car, then the streamliner train, and eventually the rocket ship.

The Lunch Wagon: 1872-1910

Walter Scott of Providence, Rhode Island, considered the father of the American diner, first offered food for sale through a side window in a converted express wagon to employees of the Providence Journal in 1872. This first lunch cart was only large enough to hold Scott and the food he served(2). Scott’s idea was quickly adopted by other entrepreneurs in the late 1880s and 1890s. However, it was Thomas H. Buckley from Worcester, Massachusetts, who became known as the “lunch wagon king.” His first wagon was built in 1888, and by 1898 his firm, The New England Lunch Wagon Company, had established sites in 275 towns nationwide(3). Later lunch carts had an enclosed body, a kitchen at the rear serving from behind the counter, and a door on one side for customers. On one side was a pedestrian order window, and on the other was a “take-out” window for carriages.

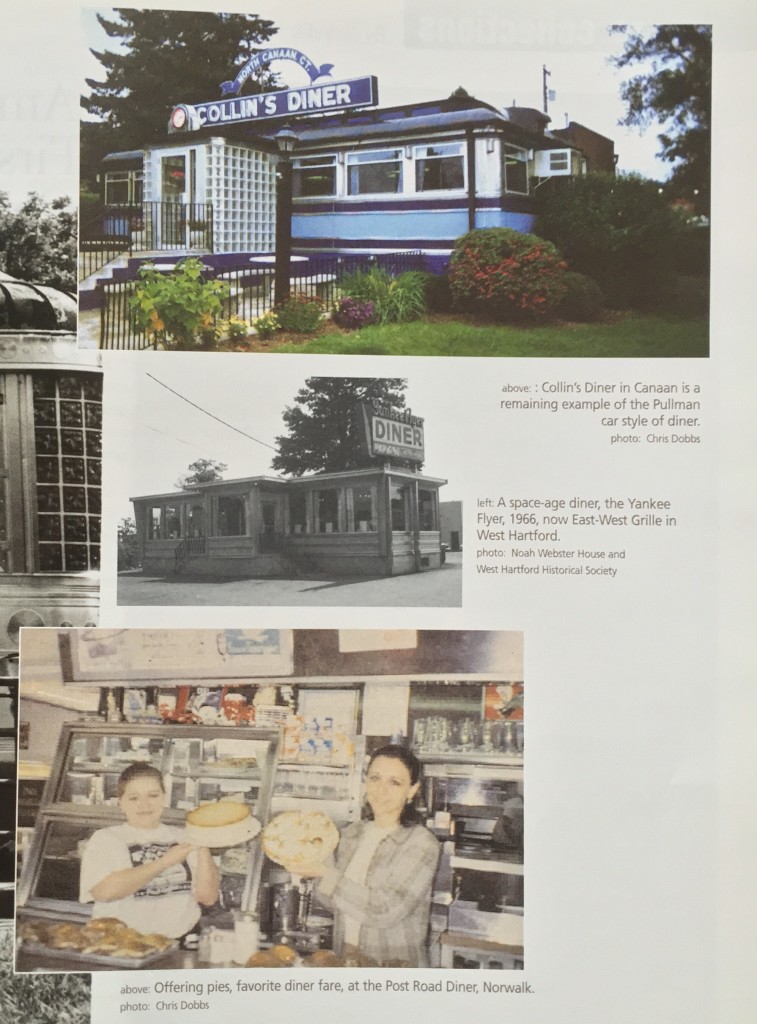

From their inception, diners became known for their home-cooked food. Sandwiches, pies, cake, coffee, and milk were often staples on the early lunch wagon menus. A 1909 menu includes corned beef, corned beef hash, ham and beans, beef stew, lamb tongues, coffee and rolls, sandwiches, pork and beans, cold ham, hot frankfurters, boiled eggs, coffee and doughnuts, and as assortment of pies(4). Hearty and simple food such as this was extremely popular for the customers, primarily working men, that these early diners served.

From their inception, diners became known for their home-cooked food. Sandwiches, pies, cake, coffee, and milk were often staples on the early lunch wagon menus. A 1909 menu includes corned beef, corned beef hash, ham and beans, beef stew, lamb tongues, coffee and rolls, sandwiches, pork and beans, cold ham, hot frankfurters, boiled eggs, coffee and doughnuts, and as assortment of pies(4). Hearty and simple food such as this was extremely popular for the customers, primarily working men, that these early diners served.

The Pullman Car: 1910-Early 1940s

By the early 20th century, as electric trolleys and the automobiles began to replace the horse-drawn carriage, the old lunch wagons appeared obsolete and decrepit to a society primed for the future. Desperate to revitalize their image, lunch wagon manufacturers looked to a form that had captivated Americans for nearly half a century: the Pullman railroad car(5).

At the same time that lunch carts were experiencing an image problem, New England cities often limited the carts’ operations on the street from dusk to dawn. To resolve this situation, many owners found permanent sites where they could get around city ordinances. The result was an increase in wagon size and a decrease in wheel size. This extended vehicle with small wheels suggested a railroad car.

Skee’s in Torrington, listed on the National Registry of Historic Places and possibly the oldest diner in the state (though currently closed and looking the worse for wear), is a prime example from this era. This Jerry O’Mahony, Inc-made diner was first introduced in the company’s 1928 catalog as the “Monarch.”(6) It features arched ornamental sash-windows with vertical panels reminiscent of many late 19th-and early 20th-century railroad cars. Even the placement of the exterior doors on each end gives the impression of a train. The marble counter, row of stools, and geometric tile-work on the floors and elsewhere create a sense of movement and a modern, hygienic feeling. The diner’s mahogany finish work embodies the elegance characteristic of early 20th century travel.

At the turn of the century, railroad transformations, including the introduction of the monitor roof and steel, influenced diner construction(7). Many diner manufacturers not only incorporated steel construction but took the image of the railroad car to an extreme. The 1941 Middletown diner named Squeak’s (which was recently moved by a Canadian collector and is now in storage) was a perfect example of such zeal, with its long monitor roofline and elongated windows. Collin’s Diner, a 1942 Jerry O’Mahony, Inc-made diner in Canaan, is a remaining example of this style. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Collin’s features a sky-and cobalt-blue exterior that, like the marble countertops and wood paneling of its interior, is maintained in pristine condition.

From Train to Speeding Bullet-Streamliners: 1934-1950s

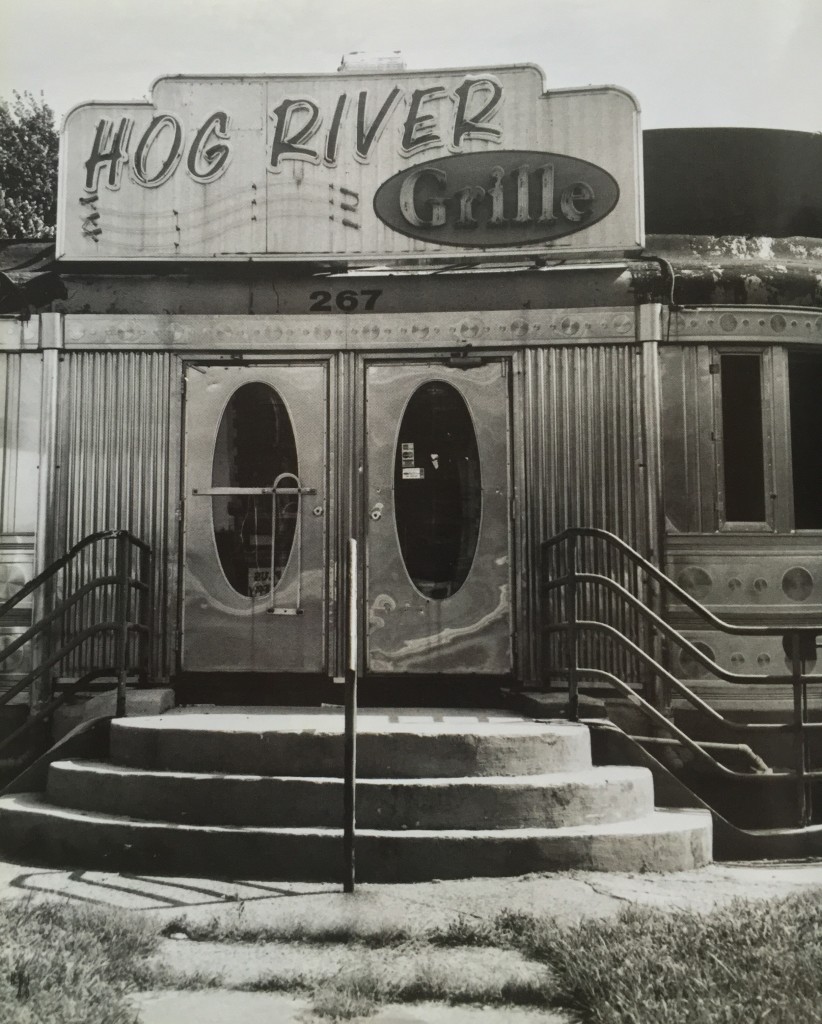

With plummeting ridership during the 1930s, the railroad industry looked toward aviation design and the “streamliner” trains such as the 1934 Burlington Zephyr, which incorporated cutting-edge stainless steel. Diner manufacturers followed suit. The shift from rigid lines to more malleable stainless steel curves allowed the hard-edged box design of the earlier Pullman car to give way to a smooth and rounded stainless-steel shell. Windows were stretched horizontally to look like the popular passenger railroad cars of the streamliner era, glass building blocks formed sleek shapes, and horizontal fluted patterns in the stainless steel evoked railway cars’ exterior “speed lines.”

A key example of such design is a 1940 Sterling diner recently moved to East Granby from Gloucester, Massachusetts. (Owner Tammy Tanner is restoring the structure and plans to open for business later this year.) Other streamliner diners in Connecticut include the Paramount-built Aetna Diner on Farmington Avenue in Hartford (most recently housing Dishes restaurant), with its rounded glass-block corners and stainless steel exterior, and the ever-popular Zip’s diner in Dayville.

As Zip’s demonstrates, diners’ interiors were dramatically altered during the 1930s and 1940s as big-ticket amenities such as fancy tile-work, mahogany, marble, and leather were supplanted by new, less expensive materials. Pressed stainless steel was used to create lighting fixtures, decorative moldings, and backbars, whose reflective surfaces, when kept clean, gleamed invitingly. Formica was employed extensively on countertops; linoleum and concrete were used on floors, and Bakelite was used for molded shapes. Naugahyde replaced wood and leather on seats, while chrome tubing added a decorative element to interiors. Changes in diner aesthetics and culture helped diners expand their clientele; from serving mostly men, they evolved into popular hangouts for all kinds of people.

Science and the Space Age: 1950s-1960s

The 1950s and 1960s were turbulent times for the American diner as for the country in general. Increased competition from new restaurants and changing public expectations brought drastic changes. As science, technology, and transportation rocketed into the space age, so did the diners. In many ways the “Space Age” diner was a popular interpretation of the International Style in architecture. Curvilinear, boomerang, and geometric shapes borrowed from industrial technology came to typify this aesthetic.

Diners such as the old Yankee Flyer, now the East-West Grille on New Park Avenue in West Hartford, demonstrate the influence that the space race had on diner architecture. Windows became flared and elongated; entrances often suggested rocket launching pads; and overhands incorporated recessed lighting in celestial patterns. In extreme examples, the corners of the eaves extended well beyond the structure to simulate wings in flight.

The End and the Beginning

The rocket diners, a populist interpretation of America’s rocket obsession with outer space and science, was short lived. And with its demise came the end of the long relationship between diner adesign and transportation. By the 1970s, many diners began to be transformed into large family restaurants with Colonial, Mediterranean, or Tudor characteristics. But a wave of nostalgia in the 1980s and 1990s reinvigorated the “retro” style, and many diners were restored to their original, transportation-inspired designs.

The Aetna Diner, more recently the Hog River Grille and now Dishes Restaurant in Hartford, is an example of a streamliner diner. Photo: Nancy O. Albert

Today, there are numerous Greek diners across Connecticut, and many of the old American-style diners have been adapted into restaurants serving a broad range of culinary offerings. Diners continue to be popular—for the glimpse they offer into bygone days, for their good food, and for a homey quality that never goes out of style. Sally Rogers and Howard Bursen might have said it best as they paid homage to the American diner in their 1984 album Satisfied Cousins: “This album is dedicated to all the independent diners like Zip’s, where real people cook real food for customers who have names.”

Special Thanks: Richard J.S. Gutman; the Johnson and Wales Culinary Archvies and Museum; Tammy Tanner; Zip’s Diner.

Chris Dobbs was executive director at the Noah Webster House and West Hartford Historical Society. He has been fascinated with diners ever sicne his childhood and performed extensive research on their architecture and evolution during his graduate studies at Cooperstown Graduate Program, Cooperstown, New York.

Explore!

“Frankies Hog Dogs,” Fall 2010

“Shack Attack: Classic Roadside Eateries,” Spring 2012

Read more stories about Food & Drink in Connecticut history on our TOPICS page.

Footnotes

(1) Judith Sigeal Leif. “The American Diner: a Meeting Place of 20th-century Building Material,” Traditional Building (Jaunuary/February 1995): 49-50.

(2) Richard Gutman, Elliott Kaufman, and David Slovic. “‘Slice of Pie a Cup of Coffee–That’ll Be Fifteen Cents, Honey,’ A Last Look at an American Institution,” American Heritage 28 (April 1977): 69.

(3) Gutman, Kaufman, and Slovic, 8-9.

(4) Richard J.S. Gutman, American Diner: Then and Now, (Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press, 2000): 38.

(5) Richard J.S. Gutman and Elliott Kaufman, American Diner (New York: Harper and Row, Publishing, 1979), 16-36

(6) Skee’s has often been given the date of c. 1920, which would make it one of the oldest diners in existence. However, the 1928 Jerry O’Mahoney Inc. catalog that introduces this diner model suggests that it could not be any earlier than 1928. This date still makes it rare and most likely the oldest diner in the state of Connecticut.

(7) John H. White, Jr., The American Railroad Passenger Car (Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press, 1978): 48-49.