By Lynne Brickley

(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Spring 2008

Subscribe to receive every issue!

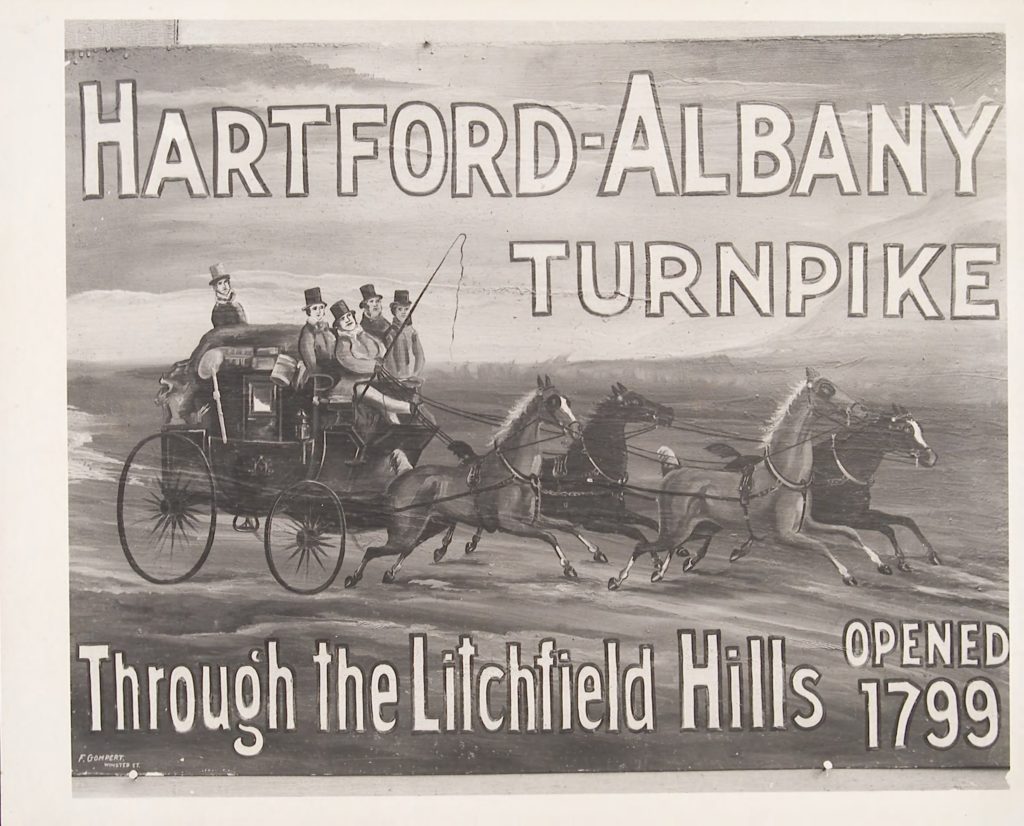

From 1790 through the 1830s, Litchfield was a nationally recognized center of economic, social, political, educational, and cultural prominence. That “golden age” coincided with Connecticut’s peak period of building turnpikes and establishing stagecoach lines. Though now considered a bit off the beaten path, at the turn of the 18th century Litchfield was a cosmopolitan town at the hub of main roads connecting cities and towns throughout the new nation. These major arteries and their stagecoach lines played a key role in what historians of Litchfield have described as its period of glory.

In the early Republic, the town was nationally known for Tapping Reeve’s Litchfield Law School, founded in 1784, (See “The Influence of the Litchfield Law School, Fall 2016) and Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy, opened in 1792 (See “Piece by Piece: Stitching Together the History of Litchfield’s Female Academy, Summer 2007). Until 1833, when the law school closed and the female academy went into decline, the schools were among the most famous educational institutions of the period. Between 1792 and 1833 the two schools together attracted to the town each year as many as 150 young men and women from all across the nation. This broad-based enrollment was the schools’ most outstanding feature; few educational institutions of the day, even the men’s colleges, attracted as many young people from such distant places.

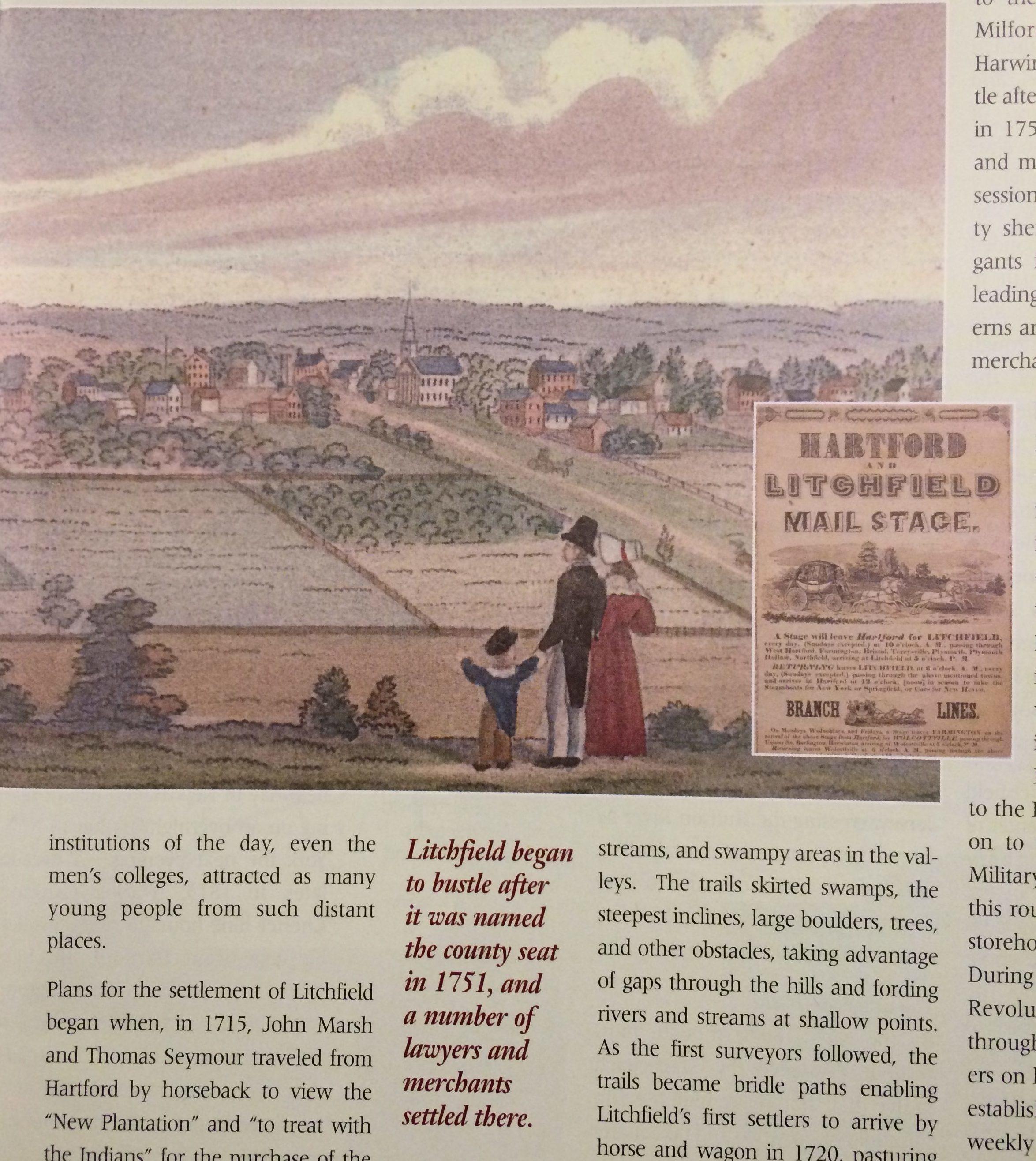

Plans for the settlement of Litchfield began when, in 1715, John Marsh and Thomas Seymour traveled from Hartford by horseback to view the “New Plantation” and “to treat with the Indians” for the purchase of the “Western Lands.” They rode over established roads as far as Farmington and from there traveled west on narrow woodland “trodden paths” made by Indians to the Naugatuck River and up the five miles of wooded hills to what is now Litchfield. Along the way they crossed numerous ridges, all running north to south, with rivers, streams, and swampy areas in the valleys. The trails skirted swamps, the steepest inclines, large boulders, trees, and other obstacles, taking advantage of gaps through the hills and fording rivers and streams at shallow points. As the first surveyors followed, the trails became bridle paths enabling Litchfield’s first settlers to arrive by horse and wagon in 1720, pasturing their livestock periodically, as they cleared an even wider tract through the forest.

As in most New England settlements, footpaths developed first between houses and the center, with its town green and church, and from there to outlying farm lots. By the 1740s roads were laid out from the village to the township lines, connecting it to the neighboring towns of New Milford, Goshen, Woodbury, and Harwinton. Litchfield began to bustle after it was named the county seat in 1751, and a number of lawyers and merchants settled there. Court sessions and business with the county sheriff brought lawyers and litigants from throughout the county, leading to the opening of more taverns and increased business for local merchants.

During the Revolution Litchfield was considered a “safe” town as it was located far from the threat of British invasion that menaced Connecticut’s coastal and river towns and the coastal “Post Road.” The town became an important way station along what was known as “the great inland route” from Boston to Hartford to New York City and to the Hudson River, and from there on to the north, west, and south. Military supplies were shipped on this route, and several large military storehouses were built in Litchfield. During and immediately after the Revolution mail was carried throughout the country by post riders on horseback. In 1791 Litchfield established its own post office, with weekly post rider services to Hartford and twice-a-month service to New York City. The following year, President Washington signed the Postal Service Act establishing the United States Post Office Department, which contracted for stage lines to carry mail from New York to Hartford, passing through Litchfield. This led to the creation of many new stagecoach lines, which carried both mail and passengers.

The end of the Revolution resulted in an increase in inland travel and shipping, more importation of mercantile goods, and a rise in agricultural production. This brought a boom in economic activity to Litchfield. Local farmers responded to post-war demand and began to export agricultural products and livestock to distant markets through the wealthier merchants of the village, who acted as middlemen. The merchants had the capital to buy local goods and transport them to New Haven, Hartford, the Hudson River, and New York City. The production of goods for markets outside the local area created even more demand for better roads, ushering in what Litchfield’s first published historian, Payne Kenyon Kilbourne, referred to as the “Age of Turnpikes.”

The end of the Revolution resulted in an increase in inland travel and shipping, more importation of mercantile goods, and a rise in agricultural production. This brought a boom in economic activity to Litchfield. Local farmers responded to post-war demand and began to export agricultural products and livestock to distant markets through the wealthier merchants of the village, who acted as middlemen. The merchants had the capital to buy local goods and transport them to New Haven, Hartford, the Hudson River, and New York City. The production of goods for markets outside the local area created even more demand for better roads, ushering in what Litchfield’s first published historian, Payne Kenyon Kilbourne, referred to as the “Age of Turnpikes.”

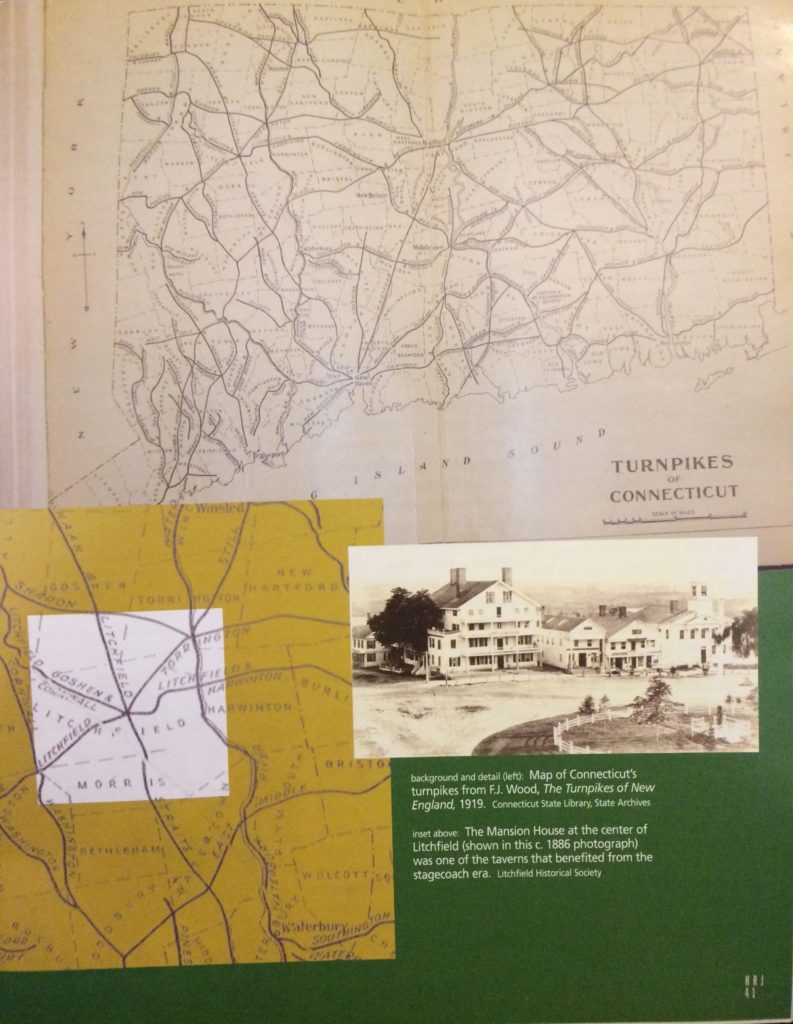

By the early 1800s, Litchfield appeared on maps to be the center of a large spider web of connecting turnpikes spreading to all points of the compass. Five roads fanned out from the village center, with two more branching off west of the center. The first to open was Strait’s Turnpike to New Haven in 1797, where passengers and goods connected with coastal packets to New York and other parts of the nation. By 1810, turnpikes connected all the towns of northwestern Connecticut, linking them to major routes in all directions.

Importing Students

While export of goods to outside markets increased, Litchfield also began “importing” an important boost to the economy—students. Initially, getting to Litchfield was arduous at best. Prior to the establishment of stagecoach lines, students coming to Litchfield from distant homes traveled by horseback, in wagons, or in family-owned conveyances. In 1797 three young women left Addison, Vermont on horseback to attend Sarah Pierce’s school. After riding 150 miles to Bennington, Vermont they were driven in a wagon to Litchfield. Young women traveling in this way arrived in Litchfield with no trunks. They had to purchase fabric and trimmings to make their clothing once they arrived. In 1800 Archibald Bellinger Clark arrived from Savannah, Georgia by horseback, accompanied by his “body servant.” William Dickinson Martin, later to become a United States Congressman and judge, left Edgefield, South Carolina on April 29, 1809. He and fellow student Robert Dickinson traveled by horse to Richmond, Virginia, from there by stage to New Jersey, crossing the Hudson River by ferry. They then took a coastal sailing packet from New York City to New Haven and continued to Litchfield by stagecoach up Strait’s Turnpike.

The Stagecoach Era

By the early 1800s, though, most students traveled by stagecoach rather than horseback, but the trip still could be crowded and take many hours. Early stagecoaches were simple wagon-like vehicles featuring a covered cab with three seats, the middle row with leather straps for riders’ backs to rest against, and an outdoor box for the driver. The passengers felt every bump and rut in the road. There were racks on the outside for trunks and bandboxes. By 1800 the design and construction of stagecoaches had improved, with egg-shaped coaches hung from the frames by leather strapping “which transformed the prior back and forth, sideways swaying, into a forward and backward rocking of the stagecoaches, which was less violent for the passengers. The stages traveled at an average rate of 4 or 5 miles an hour, with a change of horses about every 10 miles, depending on the terrain. The stagecoach companies owned the horses and rotated them on round-trip journeys.

In 1803, when Lucy Sheldon traveled from Litchfield to New York, she wrote to her mother that the stage left Litchfield “very much loaded with baggage and besides that, there were twelve passengers.” Lucy’s stage left Litchfield at 10 a.m. and arrived in New Haven 12 hours later. She spent that night and the next day in New Haven before sailing on an overnight packet to New York the next evening. A decade later, in 1815, it took Caroline Chester nine hours to ride 35 miles by stage from Hartford, through West Hartford, Farmington, Burlington and Harwinton, to attend school in Litchfield. Roads that were less traveled and less improved could make the journey even longer. In 1833 it took the stage between Litchfield and Sharon 14 hours to go only 24 miles. And if you happened to miss the stage, you didn’t have many options for getting to your destination. Susan Masters of New Milford, a student in Litchfield in 1805, recalled that she and a cousin stayed dressed and sat up all night “from fear of being left when going home on vacation.”

Most stagecoaches began their routes well before dawn, as early as 3 a.m., traveling 10 or more miles before breakfast. This did not stop them from advertising, as Hiram Barnes did for the Litchfield, New Milford, Danbury, and Norwalk Mail Stage in 1829, the claim “No Night Traveling,” even as the advertisement noted that the stage left Litchfield at “3 in the morning.” Passengers on that line spent the next night in Danbury, leaving for Norwalk in time to catch a steamboat to New York City.

Stagecoach lines generally advertised that each passenger was allowed 14 pounds of baggage for free and that 100 or 150 pounds would cost “the same as a passenger.” Baggage was carried on a rack on the outside of the stage, wrapped in a tarpaulin and strapped down. In 1809 Catherine Van Schaack wrote of her two-day stagecoach trip from Kinderhook, New York, along with three other young women traveling to the Litchfield Female Academy. After arriving at Sheffield, Massachusetts at the end of the first day’s travel, they discovered one of their trunks had fallen off the stage, forcing the stagecoach and passengers to retrace their route until the lost trunk was found.

The trunks carried by stagecoach passengers were small, round-topped, wooden-framed, and covered in hide or fur. Often the owner’s initials were studded in brass nail-heads in the wood. Young women also carried bandboxes, oval-shaped, cardboard boxes covered in patterned wallpaper, and various other bundles, which they kept with them on their laps or under their feet inside the stagecoach. In 1818 William Williams traveled from New Haven to Litchfield, sharing the stagecoach with 10 passengers, including “six Misses bound to school. In all, the stage was loaded with “50 trunks and 71 Bandboxes.”

It is almost impossible for us today, in an age of easy global travel, to understand the time and expenditure travel in the early Republic entailed. In 1800 the average wage for an American non-agricultural laborer was $1 a day. Traveling the country’s two best roads, from New York to Boston and New York to Philadelphia, cost $10 one way. In addition, travelers had to pay for meals and lodging on route, usually about $1 a day.

Travel expenses for students coming to Litchfield from distant parts of the country greatly exceeded the price of their education. When six young women came to the Academy from Georgia in 1802, the coastal packet from Savannah to New York cost them $50 each plus $5.25 for the stage from New York to Litchfield. Tuition at the Litchfield Female Academy remained at $5 or $6 per quarter for the entire period from 1792 to 1833, although additional charges for piano, needlework, painting, and French lessons could run much higher. The high expense of travel meant many students spent years in Litchfield without returning home.

Another option for parents was to hire a private stagecoach, wagon, chaise, or various kinds of carriages as it cost about the same as the stage fare for seven or eight passengers. Often parents of Litchfield students sent their own wagons, carriages, or chaises and drivers to bring their young people home. In 1812 Academy student Marcia Averell warned her brother, who was to hire a wagon in their hometown of Cooperstown, New York, to come and fetch her and a friend, not to let their father send “a little one horse wagon,” adding that her friend “says we have acquired so much knowledge since we have been here it will require more than one horse to draw us.”

“Drivers of temperate and steady habits”

Not only was stagecoach travel expensive, it was difficult. Weather conditions, such as rain, could wash out roads, cause mud slides and rock falls, and destroy ferry landings and bridges, delaying a trip by hours or days. Stagecoaches also shared the turnpikes with herds of livestock being driven to market. Litchfield was a major gathering point for livestock being shipped to cities and to the West Indies. Stages often had to wait for drovers to move their livestock off the road.

Parents sending their sons and daughters to school in distant Litchfield placed great faith in the stagecoach driver. As a result, drivers were often seen as larger-than-life figures. Various accounts of the day note that most drivers were in fact men of large physical stature, which signaled to passengers that they were strong enough to manage the horses and stage on the perilous roads of the day. Their very physical presence, perched on the box on top of the stage, set them literally above everyone else. They were seen as men of native intelligence and wit, quick to express their opinions to any passenger, regardless of that person’s station in life. They often talked politics, and they came to be seen as symbolic of the quick-witted, clever, and shrewd democratic Yankee, equal to all and beholden to none. Still, passengers’ safety was dependent upon drivers’ sobriety and skill, and stage lines advertised accordingly. In 1818, Josiah Parks and the other proprietors of the New-Haven, Litchfield, and Albany Mail Stage informed potential customers that they provided “drivers of temperate and steady habits, who have long experience in the business.”

Hiram Barnes, Litchfield’s best-known and most colorful stagecoach driver, was a famous example of the type, both in fact and fiction. From 1820 to 1830 he drove for the stage line owned by Josiah Parks that ran between Litchfield and Danbury. Then in 1830 Barnes established his own line between Litchfield and Norwalk, where his stages met the packet schooners that took passengers on to New York City. Barnes was immortalized as the character “Heil Jones” by Harriet Beecher Stowe in her largely autobiographical and last novel Poganuc People, published in 1878.

Litchfield’s heyday began to evaporate in the 1830s. The Litchfield Law School closed as colleges began to establish their own law departments. Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy lost its fame in 1833, when its head John Pierce Brace left to take over the Hartford Female Seminary. The town’s mills and manufacturing companies were unable to use new technologies that demanded greater waterpower than the area’s small streams and rivers provided. In 1837 the first railroad in the area reached New Milford, 18 miles south of Litchfield, replacing the New York stage line. The Naugatuck line came up the river valley to East Litchfield in 1848. Litchfield was left much as it was, isolated high on its hill, while valley villages such as Waterbury and Torrington developed into large cities.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, just as they were disappearing, stagecoaches of the early national period became important images in the iconography of the colonial revival. Litchfield became the pre-eminent example of a colonial-revivalized New England village, with its consciously renovated houses, commercial buildings, and town green, all redesigned to approximate the imagined colonial past. Litchfield’s isolated, rural character in the late-19th and early-20th centuries contrasted sharply with its role as an important hub of transportation, politics, and education just a few decades earlier. Central to this proudly recalled past was the network of turnpikes and stagecoach routes that had served the town.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, just as they were disappearing, stagecoaches of the early national period became important images in the iconography of the colonial revival. Litchfield became the pre-eminent example of a colonial-revivalized New England village, with its consciously renovated houses, commercial buildings, and town green, all redesigned to approximate the imagined colonial past. Litchfield’s isolated, rural character in the late-19th and early-20th centuries contrasted sharply with its role as an important hub of transportation, politics, and education just a few decades earlier. Central to this proudly recalled past was the network of turnpikes and stagecoach routes that had served the town.

Explore!

The Litchfield History Museum and the Tapping Reeve House & Litchfield Law School are open Tuesday through Saturday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sunday 1 to 5 p.m. from April 14 through November 25. Group tours are available all year by appointment.

“A New Life for the Merwinsville Hotel,” Spring 2020

“The Litchfield Congregational Meeting House,” Winter 2005/2006

“Civil War: Conflict in Litchfield,” Spring 2011

“Flying the Banner for Temperance,” Winter 2008

“Stitching Together the History of Litchfield’s Female Academy,” Summer 2007

Subscribe to receive every issue!