By Garrett McComas

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Spring 2023

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In 1880 brothers Charles and Augustus Storrs donated land and money to start an agricultural school in Mansfield, Connecticut. A year later, Governor Hobart Bigelow signed legislation to accept the building of the former Mansfield Orphanage, a few barns, 170 acres of land, and $6,000, establishing Storrs Agricultural School. After a series of expansions, the school would go on to become the University of Connecticut. Today UConn has an endowment valued at $602 million, a 4,400-acre main campus, and satellite campuses in Avery Point, Stamford, Hartford, and Waterbury.

But what is the story of this land and its people before 1880?

The history of UConn, much like the history of the United States, is rooted in the control of land and wealth. Land Grab CT (landgrabct.org) is an interrogation of the history of UConn through the lens of colonialism and the dispossession of Indigenous people. The Land Grab CT team consists of students, faculty, and staff at UConn from Greenhouse Studios, the Native American and Indigenous Students Association (NAISA), and the Human Rights Institute.

The University of Connecticut is one of 52 U.S. institutions of higher education designated as a “land-grant institution,” established through the Morrill Act of 1862. The original act called for “Donating public lands to the several States and [Territories] which may provide colleges for the benefit of agriculture and the Mechanic arts” and resulted in the grant of nearly 11 million acres of land. Land-grant institutions are often seen as oriented toward public good and were conceived of as having a democratizing effect by extending higher education to the “common man.” However, where the land came from, how it was “donated,” and how the land became “public” is often elided from their histories.

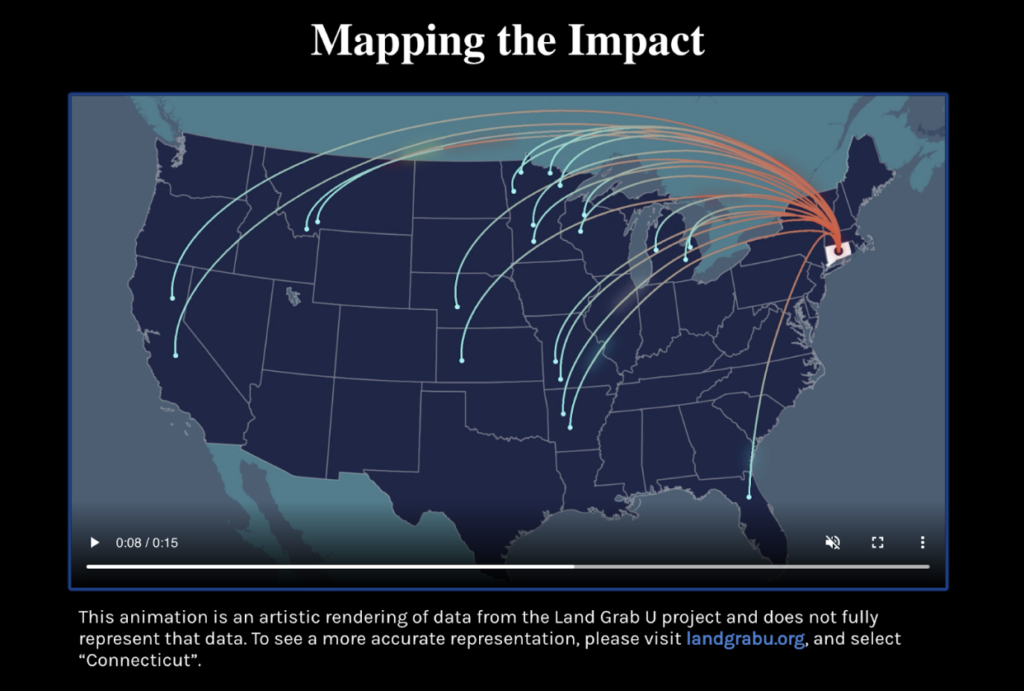

In early 2020 the Land-Grab Universities (landgrabu.org) project, executed by Tristan Ahtone, Margaret Pearce, Kalen Goodluck, Geoff McGhee, Cody Leff, Katherine Lanpher, and Taryn Salinas published a massive amount of data tying the 52 land-grant institutions to nearly 11 million acres, 250 of the Indigenous communities land was taken from, and more than 160 violence-backed treaties. Land Grab CT contextualizes the data relevant to the state of Connecticut.

The team began with three clear goals: to educate UConn’s community about the nature of land-grant status, raise awareness about UConn’s poor investment in Native relations, and lay some groundwork for restorative justice and reparations. Land Grab CT’s interactive website offers a wealth of historical context. The National Timeline explores the system of national land claims practiced by European colonial powers and their justifications for colonial expansion, which are rooted in their false assumptions of white supremacy and inferiority of Indigenous peoples. These continue to be enacted in policy and law.

The Morrill Act of 1862 was passed in the same year as the Pacific Railroad Act and the Homestead Act. These acts were a transfer of wealth to white colonists made possible by hundreds of years of state-sponsored war and violence toward Indigenous people in the so-called “Indian Wars.” They brought the newly stolen lands in the American West into the economic system by giving white settlers land to farm, teaching them how to exploit it for profit, and making the movement of settlers and exploited resources more efficient.

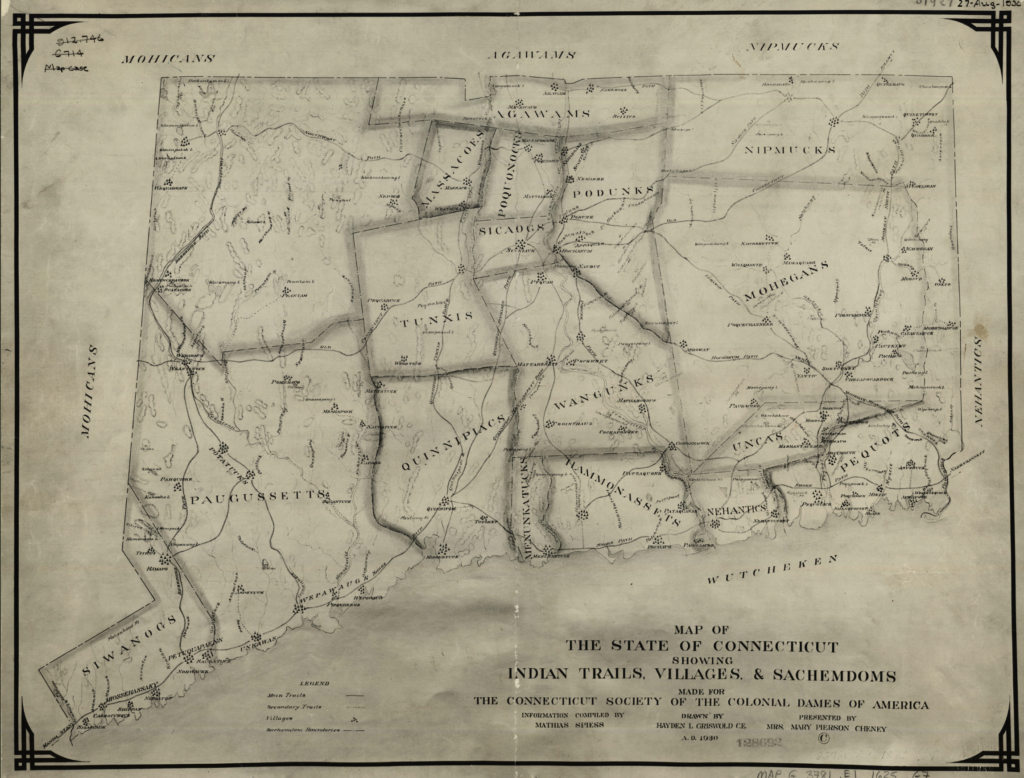

Tactics used in the “Indian Wars” originated in New England colonies in the 1600s. The website highlights settler incursions and Indigenous resistance in the Connecticut colony. After the Pequot War ended in 1637, and the Mohegan, Narragansett, and Connecticut Colony signed the Treaty of Hartford in 1638, English colonists gained control of the land where UConn stands. In 1662, 19 men, including generals from the Pequot War, became the leaders of the government through a charter that established Connecticut as a royal colony, but preserved many of its Puritan laws and governmental structure. From 1675 to 1676 a Wampanoag Sachem, Metacomet (also known as King Philip), led an unsuccessful rebellion against the continued encroachment of the settlers. In the aftermath of that war, the remaining Indigenous people in the area where UConn stands, including non-combatants, were imprisoned, enslaved, or removed.

In 1703 Mansfield, the town in which UConn is located, was incorporated and named after Colonel Moses Mansfield, who “routed a body of hostile Indians” in the area. Among the original grantees of the town was Samuel Storrs, of whom Charles and Augustus Storrs were descendants. Established in 1881, Storrs Agricultural School became Storrs Agricultural College in 1893 after receiving Connecticut’s land-grant status.

Land Grab CT challenges UConn’s history and its narrative of itself. Connecticut was given 178,190.04 acres through the Morrill Act. The state raised $135,000.84 from its sale and gives UConn interest payments in perpetuity. UConn also receives payments from subsequent acts tied to land-grant institutions and billions of additional state funding.

Since the launch of the website the project team has conducted numerous interviews, dialogues, presentations, and events to educate and empower the UConn community. The hope has always been that, by helping the UConn community better understand its own history, the university will be better positioned to begin to repair relationships with Native people at the university, within the state, and within other states that it’s tied to by the Morrill Act. Currently LandGrab CT is focused on advocating for scholarships for and investments in Indigenous communities.

Garrett McComas is a fellow at Greenhouse Studios in the Homer Babbidge Library at the University of Connecticut.